Debunking Popular Nonsense About Income Mobility in America

So what if the rich are richer than ever? American income mobility is still strong.

"Young people are exploited!" "Income mobility is down!" "Poor people are locked into poverty!" Those are samples of popular nonsense peddled today.

Leftist economist Thomas Piketty's book Capital in the Twenty-First Century has been No. 1 on best-seller lists for weeks (with 400 pages of statistics, I assume Capital is bought more often than it is read). Piketty argues that investments grow faster than wages and so the rich get richer far faster than everyone else. He says we should impose a wealth tax and 80 percent taxes on rich people's incomes.

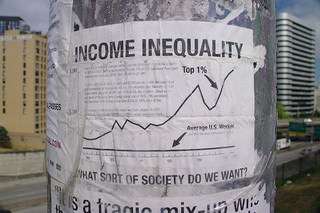

But Piketty's numbers mislead. It's true that today the rich are richer than ever. And the wealth gap between rich and poor has grown. Now the top 1 percent own more assets than the bottom 90 percent!

But focusing on this disparity ignores the fact that over time, the rich and poor are not the same people. Oprah Winfrey once was on welfare. Wal-Mart founder Sam Walton was a farmhand. When markets are free, poor people can move out of their income group. In America, income mobility, which matters more than income inequality, has not really diminished.

Economists at Harvard and Berkeley crunched the numbers on 40 million tax returns from 1971-2012 and discovered that mobility is pretty much what The Pew Charitable Trusts reported it was 30 years ago.

Today, 64 percent of the people born to the poorest fifth of society rise out of that quintile—11 percent rise all the way into the top quintile. Meanwhile, 8 percent of people born to the richest fifth fall all the way to the bottom fifth. Sometimes great wealth makes kids lazy and self-indulgent, and wrecks their lives

Also, the rich don't get rich at the expense of the poor (unless they steal or collude with government). The poor got richer, too.

Yes, over the last 30 years, incomes of rich people grew by more than 200 percent, but according to the Congressional Budget Office, poor people gained 50 percent. That growth should matter more than the disparity. Piketty's data reveal times in our history when income inequality decreased: during world wars and depression. Do we want more of that?

It's right to worry about the plight of the poor, but not everything done in their name really helps them— minimum wage laws, for example.

I've had hundreds of employees whom I paid nothing: student interns. Unpaid internships were allowed for years, because it was understood that interns learn by working. My interns learned a lot. Many went on to successful careers in journalism. One won a Pulitzer Prize. Many said they learned more working for me than at college (despite $50,000 tuition). They benefited and I benefited. Win-win.

So for years government ignored Labor Department rules that decreed unpaid internships legal only if an employer gets "no immediate advantage" from the intern. Geez, who wants that? Of course I got an advantage from my interns. That's why I employed them!

Recently, President Barack Obama's Labor Department announced it would enforce the internship rules, and some interns sued their former employers, claiming internships were "unfair." Charlie Rose forked over a quarter of a million dollars. Word spread, so now unpaid internships are vanishing.

Some people say it's good that unpaid internships are gone, because they are unfair to poor people, who can't afford volunteer work. But getting rid of opportunities does nothing to help anyone. Employers lose and students lose.

Difficult as it can seem to make your own way in this world without a phony government promise that you'll be taken care of, or that every job will pay at least $15 an hour, success happens when markets are relatively free. Individual initiative creates new things, companies, job opportunities—whole new ways of life—that make the world better for all of us.

Government "help" ends up doing harm. Leave people free—both as workers and employers—to pursue opportunities they find worthwhile, and we will prosper in ways government planners could never imagine.

Show Comments (287)