Could a Small Stadium Do Big Good?

Maybe small ballparks could economically justify their existence, though not necessarily public investment.

Is everything we know about sports stadiums wrong? Not really. But it might not always be right, either.

What we know—based on decades of research—is that publicly financed sports stadiums are a sucker's bet for everyone except the rich team players and their even richer owners.

Analysts from every corner of the ideological spectrum agree that revenue from stadium projects rarely if ever covers their costs. The big projects seldom ignite brush fires of development around them. The money fans spend at the games is money they could have spent at other local attractions, but didn't. And a lot of it flees the region in the pockets of players and owners who live elsewhere (payroll accounts for 60 percent of a pro ball club's expenditures). In some cases, taxpayers are still paying off debts incurred for facilities (e.g., Giants Stadium) that no longer even exist.

Bottom line: Contrary to the cheerleading of civic boosters, having a big-league sports team in your area actually hurts the economy. Building that team a fancy new arena hurts it even more.

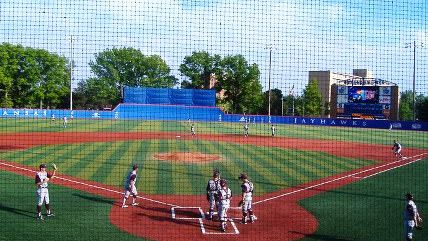

All of this is true—at least regarding big-league sports. But what about minor league clubs, and minor league stadiums?

Richmond's AA-league Flying Squirrels have complained about conditions at The Diamond ever since they came to town. They would like a new place to play. Some heavy hitters around town would like them to get one. Whispers are flying about a proposal by Mayor Dwight Jones to build them a facility in Shockoe Bottom —even though a whopping 67-22 majority of area residents think any ballpark should stay where the existing one is, on the Boulevard near I-95.

Could this story end like so many others, with elected leaders conspiring with fat cats to fleece the public for private gain? Perhaps. But some recent research suggests smaller clubs and smaller facilities might not be the economic sinkholes their bigger cousins are.

The work comes from Nola Agha, an assistant professor of sports management at the University of San Francisco. It appears in the Journal of Sports Economics and arrives at what Agha terms "an unexpected outcome": Certain types of teams and facilities can produce gains in regional income (albeit small ones: about $67 to about $117 per capita). This contradicts "the vast majority of academic research" on big-league sports, which "has found nonpositive effects on income…employment…sales tax revenues…and spending."

You'll pretty much have to take Agha's word that her conclusions are solid—unless you're comfortable with terms such as multicollinearity and homoscedasticity. But Agha, whose data set included "all of the teams that played minor league baseball between 1980 and 2006," offers some plausible reasons smaller franchises might confer benefits larger ones do not.

For instance: "Teams can theoretically…generate substantial new spending by out-of-area residents or discourage residents from spending outside the local economy. Both of these are more likely to occur in geographically isolated metro areas." (That's bad news for Richmond, which lies just a short hop from Charlottesville, Hampton Roads, D.C. and Baltimore.)

What also might help? Using the stadium for unrelated events, such as marching-band competitions. Coordinated marketing by diverse civic groups. And team stability, which can build community identification. There's a point in Richmond's favor: "Independent teams are drastically less stable than affiliated teams," which leads to "lower levels of regional interest, support, and visitor spending…Independent teams stayed in (a metro area) an average of 4 years while affiliated franchises averaged 16 years…As a whole, independent teams are not associated with gains in local area per capita income."

Also worth mentioning: The minor leagues are not homogenous, and neither are their economic effects. AAA teams, A+ teams, AA stadiums, and rookie stadiums are better for their communities than other categories. What's more, Agha cautions that her research doesn't include any cost-benefit analysis, "so there is no implication that cities should invest in AA or rookie stadiums." Stadiums could confer some economic benefits yet not produce enough to recoup their costs.

And besides: This is just one study. Other research could contradict it. Other economists could pick it apart. Anecdotal evidence could offset it: Witness Gwinnett, Ga., which built a stadium to lure the AAA Braves away from Richmond—and which has seen none of the attendant promises come true.

All the same, the work needs noting. The economic case against sports stadiums used to be open and shut in every instance. Now, in some cases, it is simply open.

This column originally appeared in the Richmond Times-Dispatch.

Show Comments (15)