The Volokh Conspiracy

Mostly law professors | Sometimes contrarian | Often libertarian | Always independent

New on NRO: "This Constitution Day, Celebrate the Triumph of Originalism"

"As we celebrate the Constitution’s 238th birthday, originalism is now the dominant approach — on the left and the right — to interpret the Constitution."

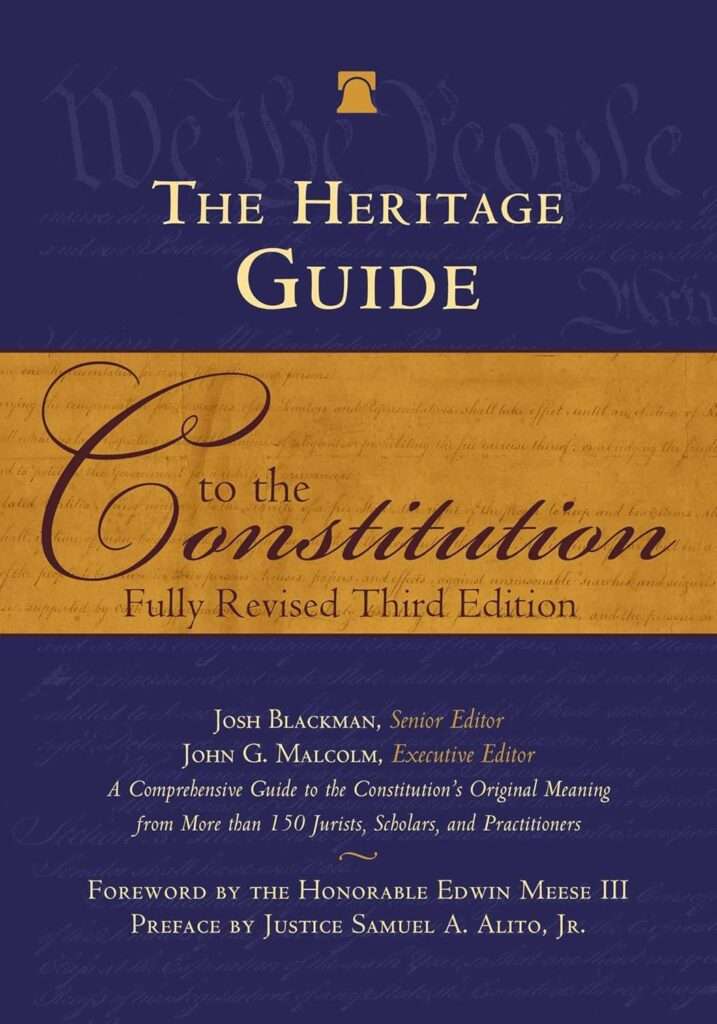

In honor of Constitution Day, and the launch of the Heritage Guide to the Constitution, John Malcolm and I authored an essay on National Review Online, titled: "This Constitution Day, Celebrate the Triumph of Originalism."

In honor of Constitution Day, and the launch of the Heritage Guide to the Constitution, John Malcolm and I authored an essay on National Review Online, titled: "This Constitution Day, Celebrate the Triumph of Originalism."

Five decades ago, originalism wasn't even an -ism. In the academy, at the bar, and on the courts, the Constitution was interpreted as a living, breathing document. Contemporary values mattered more than text, history, and tradition. Yet today, as we celebrate the Constitution's 238th birthday, originalism is now the dominant approach — on the left and the right — to interpret the Constitution.

Even Justice Ketanji Brown Jackson said during her confirmation hearing, "I believe that the Constitution is fixed in its meaning" and that looking to "original public meaning" is "a limitation on my authority to import my own policy." Still, critics charge that lawyers and judges, lacking Ph.D.s, are not qualified to perform historical research and that originalism is partisan and lacking in any sort of neutrality. These claims do not hold up.

For nearly five years, a coalition of 30 judges, 60 academics, and 60 practitioners united to assemble a definitive, comprehensive, and neutral statement about the entire Constitution's original meaning. This ground-breaking research will be published in the fully revised third edition of the Heritage Guide to the Constitution. Justice Samuel A. Alito wrote in his preface that "the new edition of The Heritage Guide is a great place to start" for all Americans who "want to understand what our Constitution means."

These judges, scholars, and advocates who contributed to this book teach us how to determine the Constitution's original meaning in the right chronological order: the history before 1787; the records of the Constitutional Convention; the ratification debates; early practice in the legislative and executive branches; and finally, judicial precedent. More than 200 essays break down every clause of the Constitution through these five steps.

Here are the five steps:

First, what were the origins of the text in the Constitution? . . . .

The second part of the originalist inquiry focuses on what the 55 delegates accomplished in Philadelphia to frame the Constitution. . . .

The third, and perhaps most important phase, was the ratification debates. . . .

The Constitution was formally ratified in 1788, and the new government assembled in 1789. At that point, the fourth phase began. How did the early actors in our government understand the Constitution? . . .

The fifth inquiry, finally, turns to the courts: What have judges, especially on the Supreme Court, said about a particular clause of the Constitution?

We conclude:

This five-step approach reflects originalist best practices that students, lawyers, and the judiciary should follow. The Supreme Court has often referred to the Constitution's text, history, and tradition to understand the document's original meaning. It is important to approach these inquiries in the right order.

Editor's Note: We invite comments and request that they be civil and on-topic. We do not moderate or assume any responsibility for comments, which are owned by the readers who post them. Comments do not represent the views of Reason.com or Reason Foundation. We reserve the right to delete any comment for any reason at any time. Comments may only be edited within 5 minutes of posting. Report abuses.

Please to post comments

Any chance the courts will celebrate the day by admitting the second amendment says "shall not be infringed", and permits and fees are infringements?

Any chance they will admit "asset forfeiture" is unconstitutional?

Any chance anyone will care?

To add to that, any chance that Alito will admit that 4A means what it says?

A. Nope.

My problem is the plenary power doctrine. If originalism really “triumphed,” courts would revisit those 19th-century inventions that gave Congress and the executive near-unreviewable authority in areas like immigration. Some of those powers should have been added by amendment, with defined delegations, instead of smuggled in by judicial fiat.

The whole philosophical value in originalism is not letting modern power mongers expand their own power at their own whim. This is a core constitutional design principle, that government only has powers granted to it, and no more. They need an amendment, approved by the Several States and The People, if they find it wise.

European concepts, where a parliament simply inherits the full powers of tyrants they replace, is no proper answer. They are born on bended knee, begging it to give them rights.

Another issue I have is Congress delegating policymaking to the executive branch. As far as I can tell, the Constitution doesn’t grant Congress the power to hand off its lawmaking authority to other branches. Yet over time, Congress has ceded more and more responsibility — maybe because it’s easier politically — but I don’t think that’s what the Constitution prescribes.

You can predict most of modern constitutional doctrine just from the fact that judges/justices are nominated by the President, and confirmed by the Senate.

Prior to the 17th amendment, the state governments retained at least the theoretical possibility of denying a Senator who pissed them off another term, so you had some constraint on the behavior of Senators in this regard. They could only get away with confirming judges who were so hostile to the states' prerogatives, and no more.

The 16th amendment gave the federal government the essentially unlimited power to raise revenue over the objection of the states.

I think it's no historical accident that the vast expansion of federal power came, not after the Civil war, but instead after the 16th and 17th amendments were ratified. Those amendments broke the Constitution's careful balance of power between the states and the Federal government.

Prior to the 17th amendment, the state governments retained at least the theoretical possibility of denying a Senator who pissed them off another term, so you had some constraint on the behavior of Senators in this regard.

Yeah! I mean, if only there was some way for the state's voters to deny a Senator another term after that Senator pissed them off ... Nah, much more important that the state legislatures have that power. Can't give the voters too much direct control over who represents them.

Look, maybe you just don't want a stable division of power between state and federal governments, but if you do want it, the state governments need some way to push back against federal usurpations, not just relying on the voters.

Just like inter-branch fights at the federal or state level require the branches themselves to have some leverage, not just relying on the voters disciplining over-reaching executives or legislatures.

Look, maybe you just don't want a stable division of power between state and federal governments, but if you do want it, the state governments need some way to push back against federal usurpations, not just relying on the voters.

The voters are the legitimate holders of power in the whole of the United States. Everything about our government comes down to what the voters want. Even protecting individuals from the "tyranny of the majority" ultimately relies on enough voters wanting that to happen. As paradoxical as that is, there is no other way to protect any of our rights from government abuse short of violent revolution.

All of the mechanisms and institutions, including federalism, the courts, and the Constitution itself, that can provide checks on power start with what voters will do that reinforces and protects those institutions. The idea that we can protect people from an abusive federal government by giving more power to state governments was proven not to work by the Articles of Confederation and then by the Civil War. Pitting different branches of government against each other, or pitting state governments against the federal government, as a way to provide checks and balances is premised on each of those levels of government competing for the votes of the people.

My whole point is that it is the voters themselves that have the most incentive to get rid of Senators that do a bad job, so it makes the most sense to have voters choosing them. Not to mention that it is how the voters define what it means for the Senators to be doing a good or bad job that matters the most.

Judges are the exception to relying on voters to protect against government abuse. But, judges are strictly limited to being the referees between legislatures and the executive when it comes to political disputes. They are limited to applying and interpreting the law in the cases before them, and they have no authority to set or enforce policy beyond that. That is the theory, at least. Needing judges to be people that are experts in the law as well as people that will not seek to advance their own careers, interests, and beliefs using their position, the idea was for one branch that is elected, the executive, to nominate judges, and for the other elected branch (or one chamber of it, at least) to consent to those appointments. The hope was that making it a potentially adversarial process to appoint judges would lead to fewer judges that would step outside the vision for their role.

Ultimately, your argument, like all that want to return the choosing of Senators to state legislatures, relies on the idea that those state legislatures will have better intentions than the voters. I find that to be a ridiculous idea completely at odds with the skepticism the right says that they have of government power.

You suggest that it is unwise to rely on voters to protect their own rights like you believe that some politicians can be found that would do it better. Politicians that would have to be chosen by...voters.

Last edit:

This what scares some of us that oppose the Republican Party. It looks to us like the conservative base, mostly the MAGA faction of it, is thinking that once they choose the right people to control government, they can give them more power to make sure that the left doesn't ever get control again. They will trust Trump and those like him to serve their interests and not abuse that extra power that they have given them to fight the left. That's what your argument about the Senate looks like to me. You seem to think that you can choose the right kinds of people for state government to fight the good fight against an out of control federal government, and that they won't abuse any of the extra power that you want them to have to do that.

The 16th amendment gave the federal government the essentially unlimited power to raise revenue over the objection of the states.

...I'm trying to remember why the Constitution gave Congress any ability to raise revenue over the objection "of the states." Might have had something to do with the requirement that it needed to be unanimous. It might also have had something to do with how members of Congress were supposed to represent the people of their states and not just be a proxy for the state governments. (Well, except for those Senators we already talked about.)

Every time I hear people talk about "the states" as if they were some anthropomorphic conscious entity, I hear "the state governments," since that it the only thing they could mean that makes any sense.

When I see someone talk about "states' rights" like that, I see it used in cases where federal law, or the national government more generally, is not according to what that person wants. But their state government will do what they want. And it might even do what that person wants despite the majority of voters in that state not wanting that. But, the state government is controlled by that speaker's party because other policies are popular with the state's voters, or the state legislature is just that badly gerrymandered.

If "the states" have power instead of the federal government then, they can get what they want even if what they want isn't supported by a majority of the country. That is fine for things that only affect that state. It is fine for things really are best dealt with at the state or local government level. It is not fine for things that affect the whole country and are best dealt with uniformly across the country by the federal government.

The whole philosophical value in originalism is not letting modern power mongers expand their own power at their own whim. This is a core constitutional design principle, that government only has powers granted to it, and no more. They need an amendment, approved by the Several States and The People, if they find it wise.

That's a great theory. I put it up there with spherical cows and frictionless vacuums as far as its usefulness in the real world goes, however.

But the main problem with how you explain originalism, though, is that limiting the power of government to those specifically enumerated was not the stated goal. At least, not if you start with Robert Bork's law review article that I've seen credited as the origin of originalism.*

It's been a long while since I read the whole thing, but as I remember it, which agrees with summaries and excerpts I find now, is that Bork was much more concerned with limiting the Supreme Court's ability to find new rights in the Constitution than he was with limiting the power of government.

There appear to be two proper methods of deriving rights from the Constitution. The first is to take from the document rather specific values that text or history show the framers actually to have intended and which are capable of being translated into principled rules. We may call these specified rights. The second method derives rights from governmental processes established by the Constitution. These are secondary or derived individual rights. This latter category is extraordinarily important. This method of derivation is essential to the interpretation of the first amendment, to voting rights, to criminal procedure and to much else. . .

If anything, Bork was very concerned that the Court was improperly limiting the power of government in deciding moral questions, such as sexual behavior.

In Griswold a husband and wife assert that they wish to have sexual relations without fear of unwanted children. The law impairs their sexual gratifications. The State can assert, and at one stage in that litigation did assert, that the majority finds the use of contraceptives immoral. Knowledge that it takes place and that the State makes no effort to inhibit it causes the majority anguish, impairs their gratifications.

Bork makes an analogy that seemed irrelevant to me, before concluding:

Unless we can distinguish forms of gratification, the only

course for a principled Court is to let the majority have its way in both cases. It is clear that the Court cannot make the necessary distinction. There is no principled way to decide that one man's gratifications are more deserving of respect than another's or that one form of gratification is more worthy than another.

I don't see it as any kind of accident or coincidence that Bork was looking for "neutral" principles of interpreting the Constitution while heavily criticizing socially progressive decisions. He put the "gratification" of a socially conservative majority of voters in a town or state in knowing that they were keeping people from having the dirty sex without risking the "consequences" of pregnancy on the same plane of existence as the "gratification" of a romantic couple's physical intimacy. Maybe Bork was saying that the satisfaction of being a prude is how those people got their rocks off, and they deserved to get it without consequence more than the married couple did.

*If contemporary originalism can be assigned a definite starting point, that point must be the publication of Robert Bork’s Neutral Principles and Some First Amendment Problems. - From Robert J. Delahunty, John Yoo, "Saving Originalism", Michigan Law Review, 2015

This is a core constitutional design principle, that government only has powers granted to it, and no more.

I would also correct this statement. The core design principle of the Constitution is that Congress, and thus the whole federal government*, is only given powers that are granted to it by the Constitution. All other general powers of government are "reserved" for the states or the people, except for those explicitly denied the states. That is very broad and leaves a lot of powers for the states that the Constitution says nothing about.

*If you take seriously the idea that the President's power is only to faithfully execute the law, plus a couple of things like the pardon and appointment powers, then what limits Congress also limits the executive.

"the history before 1787"

I assume this includes British legal history. Many terms in the Constitution are imported from there and have legal history. Habeas corpus, due process, common law, equity, bill of attainder, are some examples that come to mind.

Let's see the CVs of the 60 academics.

Originalism, if it is to have any rationale as a means of legal constraint, has to be based on formally specifiable means to determine what happened in the past. By and large, judges and legal practitioners lack training, familiarity, and inclination to formulate historical queries which do not entangle the past with present-minded contaminants. If you purport to talk about the past, but in fact are focusing on the present, you are sunk in originalist quicksand.

There are academics, not many, but among the best, who do understand how to formulate queries about the past. It is about as straightforward and easy to do as to untangle the paradoxes inherent in the literature of science fiction time travel. But if originalism is to mean anything, it must accomplish that disentangling successfully.

The project Blackman outlines is thus a stretch. Experience with pro-originalist balderdash counsels low expectations this time too. But to avoid letting prejudice take over, let's see what the hopeful indicators look like. Which academics are vetting this effort for fidelity to the only queries history can properly address: queries about what happened in the past?

For a different take, see my article, "How the Federalist Society Destroyed the U. S. Constitution" at

https://alanvanneman.substack.com/p/how-the-federalist-society-destroyed

Originalism as practiced by Professor Blackman and his ilk is a fraud, designed to provide a very thin intellectual veneer for his preferred policy outcomes. The latest glaring example is the unitary executive theory he and like-minded ideologies have decided to promote now that their authoritarian is in the oval office. Such a theory would have been utter anathema to the creators of our constitution, after their dealings with the British Crown.

I agree with Hugh. Blackman and the SCOTUS justices he supports are con men. Even Bork with his dismissive characterization of the Ninth Amendment as an "ink blot" proved he cannot be trusted to have told the truth about how our Constitution protects our rights.

Blackman's support for the majority opinion in Dobbs highlights Blackman's own profound lack of integrity and lack of commitment to supporting our Constitution. That opinion was founded on SCOTUS justices' lie about, and their knowing violation of, the plain meaning of the plain text of the Ninth Amendment.

In Dobbs, the majority opinion (twice) misrepresented that the Ninth Amendment was a "reservation of rights to the people." The majority abused that lie about the meaning of the Ninth Amendment to justify the following contention and conclusion (which blatantly violated the Ninth Amendment): "The Constitution makes no express reference to a [person’s] right to [not be compelled to devote such person’s own body or liberty to support another being], and therefore those who claim that it protects such a right must show that the right is somehow implicit in the constitutional text."

Clearly, the Ninth Amendment does not state a reservation of rights. It clearly states a rule of construction that expressly prohibits judges from doing what six SCOTUS justices did, above. This is super simple and super straightforward. No judge (or lawyer) worthy of the title could read the Ninth Amendment and fail to see that it stated a clear command about how our "Constitution" absolutely "shall not be construed." Our "Constitution" NEVER can "be construed to deny or disparage" ANY rights "retained by the people" because of any mere "enumeration in the Constitution" of "certain rights."

The Dobbs majority blatantly violated the Ninth Amendment by focusing on the (irrelevant) fact that "[t]he Constitution makes no express reference to a right to [do something specific]" and then using the absence of an "express reference to a [person’s] right to [not be compelled to devote such person’s own body or liberty to support another being]" to justify shifting the burden of proof to people asserting our rights.

The Thirteenth Amendment was perfectly clear that "involuntary servitude, except as a punishment for crime whereof the party shall have been duly convicted, shall [not] exist within the United States, or any place subject to their jurisdiction."

The 9th amendment does state a rule of construction: The failure to enumerate a right is not proof that it doesn't exist.

But the 9th amendment didn't state the inverse rule, that failure to enumerate a right meant that it DID exist!

Enumerated rights are established to exist by the very fact of their enumeration. Unenumerated rights must be established by OTHER evidence.

The Dobbs majority found that other evidence lacking. They were not, as you claim, just relying on the failure to enumerate by itself.

The Dobbs majority found that other evidence lacking. They were not, as you claim, just relying on the failure to enumerate by itself.

This seems like it could be correct. But I have some issues with framing it this way. The Dobbs majority wasn't just looking at the claim for a right to abortion skeptically and finding the arguments unconvincing. They also went out of their way to find evidence, outside of the Constitution, that it doesn't exist.

This is where originalism enters into it. Originalism contends that understanding the text of the Constitution requires looking outside of the text to find out what people thought it meant. If this method were to have any validity, this wouldn't even start until after using the text, by itself, proved insufficient to decide how to apply the Constitution in the case in front of them.

As a non-lawyer, but as a citizen that has to obey the law, I would think that it is a hard rule that the law means what it says first and foremost. I really hope that all lawyers and judges believe that as a core principle of their profession. If people got to their understanding of a law by going through a convoluted path that was susceptible to their own biases, then that is an invalid understanding when it contradicts a more simple, plain reading of the words of the law. Such a biased understanding should not replace the words the law uses. This is just as true for those that wrote and ratified the Constitution and its amendments as it is for anyone living now. And it doesn't matter how popular that flawed understanding of the law is or was among either the elite or the general population.

Is a right to privacy implied by the text of the Constitution? This is the question that the 9th Amendment demands we answer. The statement in the majority opinion that Jack Jordan quotes seems to be directed this way. But I am skeptical that the majority actually asked themselves that question in good faith. Also, by a right to privacy, I mean, among other things, a general right not to be controlled by government when making highly impactful decisions for one's own life that don't affect anyone else significantly. Can the government tell me that I can't go to college and have to go to a trade school instead, because there's already too many people getting useless college degrees? Can the government tell me that I can't get a knee replacement surgery, because I don't really need it? Can the government tell me that I have to wear a helmet when riding a motorcycle? Just like abortion, these are all questions that involve the government substituting its judgement for ours, and it takes a consequential decision away from us. All of those questions would require strict scrutiny, in my opinion. (For the record, I think that a law requiring motorcycle helmets would be likely to survive strict scrutiny, though I'd have to look up if any lawsuits challenging one ever got far enough to set precedent on that.)

I don't think that the Dobbs majority approached this question in this manner, by looking at the text of the Constitution first, and "history and tradition" second.* I think that they worked with the assumption that looking at laws and traditions surrounding abortion at various points in history was the correct place to start. That is wrong, in my opinion. That is because it would bake into the Constitution any flawed and invalid understanding of the text that their sources had.

*As an aside, I think that the second order method of interpretation, when the text is insufficient, should be to examine existing precedent, not to do deep dives into history. I think that this is what legal scholars mean by "common law" or stare decisis. Case law builds up from past interpretations and rulings, and it needs to be consistent. Moving the case law in a different direction has to be done extremely carefully.

To expand on some of the examples of possible government infringements of a right to privacy that I use:

It isn't that the government wouldn't have enumerated powers that relate to some of those questions. Even enumerated powers are subject to strict scrutiny when they limit fundamental liberties.

True originalists would agree (I think) that the two most significant decisions of this century (at least) are Alden v. Maine in 1999 and Arizona State Legislature v. Arizona Independent Redistricting Comm’n in 2015.

In Arizona, the majority opinion highlighted a crucial truth and a crucial source. They emphasized the self-evident truth that “the animating principle of our Constitution” is “that the people themselves are the originating source of all the powers of government.” “The people’s ultimate sovereignty had been expressed by John Locke in 1690.” “Our Declaration of Independence, ¶2, drew from Locke.” They also quoted Locke for a crucial truth: any “Legislative” body (i.e., any state or federal legislature) has “only a Fiduciary Power to act for certain ends,” and “there remains still in the People a Supream Power to remove or alter the Legislative, when they find the Legislative act contrary to the trust reposed in them.”

Locke's Second Treatise of Government paragraphs 132, 134, 136 emphasized that whoever exercises the supreme legislative authority is sovereign. Our Constitution was designed according to the logic of Locke. In The Federalist No. 51, Madison emphasized, “In republican government, the legislative authority necessarily predominates.” At first glance, the most obvious “legislative authority” is Congress. That is true as far as it goes. As the Necessary and Proper Clause established, Congress predominates over the executive and judicial branches by having the power and duty to make all laws that are necessary and proper for governing the powers of the executive and judicial branches. But our Constitution established that the people (who "ordained and established" our Constitution) are the supreme legislative authority and sovereign.

SCOTUS in Alden and the authorities they discussed (especially Justice James Wilson's opinion in Chisholm v. Georgia) supplemented SCOTUS in Arizona and Locke in proving that the people are the supreme legislative authority and sovereign. In Alden, the majority and dissenting opinions discussed a profoundly important decision, Chisholm v. Georgia in 1793, all of which also explained how to see and prove that our Constitution clearly established the sovereignty of the people (which SCOTUS in other decisions regarding rights refers to as "ordered liberty").

If law professors, lawyers and judges gave the foregoing their due, we might all finally learn how to read our Constitution, including the Ninth Amendment, correctly.

James Wilson was the only person who signed both the Declaration of Independence and the Constitution and served on SCOTUS, He was responsible for starting our Constitution with its most profound and important words "We the People." Later, Justice Wilson wrote some of the most important, insightful words in any SCOTUS opinion. Wilson succinctly explained and proved the great power of the Preamble.

The heart and soul of our Constitution is only implicit in its text and structure: “the term SOVEREIGN” is not used in our “Constitution.” Chisholm v. Georgia, 2 U.S. (2 Dall.) 419, 454 (1793) (Opinion of Wilson, J.). But the Preamble is the “one place where it could have been used with propriety.” Id. Only those “who ordained and established” our “Constitution” could “have announced themselves ‘SOVEREIGN’ people of the United States.” Id.

The first and foremost separation of powers in our Constitution is between the sovereign people and all public servants. So “The PEOPLE of the United States” are “the first personages introduced.” Id. at 463. After introducing the sovereign (the people), the text and structure of Articles I, II and III further emphasized the people’s sovereignty. They introduced our directly-elected representatives (Congress), then, our indirectly-elected representative (the president), and, last, our unelected representatives (judges). The people “vested” only limited powers in public servants in and under “Congress” (U.S. Const. Art. I, §1), the “President” (Art. II, §1) and the “supreme Court” and “inferior Courts” that “Congress” was delegated the power to “ordain and establish” (Art. III, §1).

Harry V. Jaffa wrote that Dred Scott was an originalist decision. He did not mean that as a compliment to originalism.