The Volokh Conspiracy

Mostly law professors | Sometimes contrarian | Often libertarian | Always independent

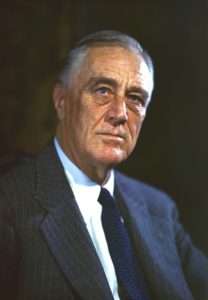

Today in Supreme Court History: July 22, 1937

7/22/1937: The Senate voted down President Roosevelt's Court-Packing plan, 70-20.

Editor's Note: We invite comments and request that they be civil and on-topic. We do not moderate or assume any responsibility for comments, which are owned by the readers who post them. Comments do not represent the views of Reason.com or Reason Foundation. We reserve the right to delete any comment for any reason at any time. Comments may only be edited within 5 minutes of posting. Report abuses.

Please to post comments

But FDR had the last laugh; He wanted to pack the Court to immediately have a majority to approve his unconstitutional power grabs, but just by hanging around long enough he got his majority and rubber stamp the old fashioned way, by nominating them as Justices died or retired.

At one point either, Truman named a Republican (Burton) to the Supreme Court; around that point all the Justices had been appointed by him or FDR.

"Now that's court packing!", screamed the Democrats 70 years later, when the shoe was on the other foot, trying to be clever, lying in a motivated power grab way.

Federalists in 1800/1 passed a judicial reform law.

They added lots of judges and the next judicial vacancy on the Supreme Court would not be filled. SCOTUS would drop down to five justices. Jeffersonians were appalled and responded with their own court bill. The battle over the courts continued.

Congress in the 1930s did pass a judicial retirement bill that helped to convince a conservative justice to retire, resulting in the first of many FDR appointments to the Supreme Court. A good retirement plan has encouraged many judges to retire.

One thing different back then from now was that "nine old men" was on the bench & there was a good chance some would soon retire. Generally, justices did not serve as long as they do now. A similar change in personnel in the short term is not likely now.

The Supreme Court majority also accepted the constitutionality of the New Deal. That was already was starting to be clear when the expansion plan was voted down. The legislation probably in some fashion influenced one or more justices.

Getting what you want without expansion doesn't seem as much of a thing today. People challenge using expansion to get certain things. But, granting it, the situation is different.

Those who support court expansion today also allege multiple nominations were tainted. Many challenge this on the merits. So be it. Again, I am not aware of a similar concern regarding the conservatives on the Supreme Court in those days.

I think expansion of the Supreme Court today is pretty much a non-starter. It isn't even supported (as compared to term limits) by a significant number of congressional Democrats (a small minority of them support proposals). It might be worthy of discussion, including talking of 15 justices with panels, and so forth.

But like in the 1930s, it very well might be the case that the ends are realistically to be obtained some other way. We shall see.

"One thing different back then from now was that "nine old men" was on the bench & there was a good chance some would soon retire. Generally, justices did not serve as long as they do now. A similar change in personnel in the short term is not likely now."

That brings up an interesting idea. Would we get fewer dramatic swings if justices were replaced more often, such as every five years? Or just to be contrary, what if the last thing every President did was appoint all new justices, deliberately meant to slow down the incoming President?

Though President Roosevelt would ultimately make nine appointments to the Supreme Court, second only to President Washington's eleven, he did not make any during his first term. Naturally, he found this frustrating and "unfair". His immediate predecessor, President Hoover, had, after all, made three appointments to the Court during his single term. The last president not to make any Court appointments during a full four-year term in office had been Woodrow Wilson, in his second term. The last president not to have made any Court appointments during his (full, four-year) first term had been James Monroe, more than a century earlier.

The last president not to make any Court appointments during a full four-year term in office had been Woodrow Wilson, in his second term.

Then came Jimmy Carter.

Presidents who made zero Supreme Court appointments during a full four-year term:

Madison (second term), Monroe, (first term), Wilson (second term), F. Roosevelt (first term), Carter (only term), Clinton (second term), G.W. Bush (first term), Obama (second term).

The three other presidents (besides Carter) who made no appointments to the Court were William H. Harrison, who died one month into office; Zachary Taylor, who died one year and four months into office; and Andrew Johnson, who, despite nearly serving a full four years, was stymied from making an appointment by the Radical Republicans in the Senate and his own ineptitude.

Proposed amendment regarding Article III

The judicial power of the United States, shall be vested in one Supreme Court consisting of nine judges and in such inferior courts as the Congress may from time to time ordain and establish. The judges, both of the supreme and inferior courts, shall hold their offices during good behavior, and shall, at stated times, receive for their services, a compensation, which shall not be diminished during their continuance in office.

The judges of the Supreme Court shall nominate, and by and with the advice and consent of the Senate, shall appoint the Attorney General for the United States. The Attorney General shall hold their office during one term of ten years.

The Attorney General shall nominate, and by and with the advice and consent of the Senate, shall appoint Attorneys for the United States for any district for which a Judge having criminal jurisdiction shall have been provided by law. They shall hold their offices for a term of eight years, eligible to succeed in office for one additional term of office.

The Attorney General and all appointed Attorneys of the United States shall be removed from office on impeachment for, and conviction of, treason, bribery, other high crimes and misdemeanors, or other behavior that renders them unfit for office

Explanation – Strengthening Judicial Independence and Reforming the Department of Justice

This proposal reforms the structure and appointment process of the federal judiciary and federal prosecutors to restore constitutional balance and protect the rule of law from political interference.

First, this amendment fixes the number of Justices on the Supreme Court at nine—permanently ending the destructive and recurring threat of court-packing. The size of the Court should not fluctuate with political winds. The independence of the judiciary depends on the stability of its structure, not on partisan attempts to reshape its composition for short-term advantage. This provision restores that stability.

Second, by preserving life tenure for judges under the “good behavior” standard and ensuring undiminished compensation, this amendment retains the core protections of Article III necessary to judicial independence. But it goes further: it removes the President from the appointment process for the Attorney General and the federal district prosecutors—positions that are too often politicized in modern governance.

Under this amendment, the Supreme Court nominates the Attorney General, who is then confirmed by the Senate. This structure ensures that the chief legal officer of the United States is accountable not to the President, but to the judiciary and to the states through their representation in the Senate. The Attorney General is appointed to a single ten-year term—long enough to remain insulated from the electoral cycle, but limited enough to ensure renewal and accountability over time.

Further, the Attorney General, once in office, nominates the United States Attorneys for each federal judicial district where criminal jurisdiction exists. These prosecutors also serve fixed terms—eight years, renewable once—ensuring continuity while avoiding entrenched fiefdoms. The power of criminal prosecution is among the most potent in government, and it must be wielded with independence, not political calculation.

This design achieves several essential goals:

Depoliticization of Federal Prosecution: By transferring appointment authority from the President to the judiciary and Senate, this amendment ensures the Department of Justice serves the law, not the executive branch’s political priorities.

Separation of Powers Reinforced: No longer will the same individual who leads a political party and seeks reelection also control the machinery of federal criminal enforcement. That conflict of interest is eliminated.

Judicial Legitimacy Protected: Fixing the number of Supreme Court Justices at nine permanently ends the periodic threats to expand or shrink the Court for political gain—preserving its independence and reputation.

Predictability Without Politicized Retirement: While some proposals seek to impose term limits on Justices, doing so without structural reform risks giving the appearance of predictability while incentivizing partisan retirement timing. This amendment maintains life tenure while other proposed amendments address political distortion in other critical areas.

Finally, by subjecting the Attorney General and all United States Attorneys to removal by impeachment and conviction—not at the pleasure of the President—this amendment further safeguards the legal system from abuse. Prosecution is too powerful to be political, and justice too sacred to be swayed by temporary officeholders.

In sum, this proposal strengthens the separation of powers, professionalizes and insulates the federal legal system, and permanently secures the independence of the Supreme Court—reaffirming the rule of law in both form and function.

This amendment fixes the number of Justices on the Supreme Court at nine—permanently ending the destructive and recurring threat of court-packing. The size of the Court should not fluctuate with political winds.

The size of the Supreme Court has changed over the years, starting at six and reaching 10 for a short time & then set at nine. The needs of the country changed. See also the size of the House of Representatives. There is a good reason an amendment involving the size of the House was not ratified.

Fixing the number at nine, only changeable by an amendment, is ill-advised. The court expansion effort reflects a wider political battle that can be applied in a variety of ways. This artificial limit won't even do much about that.

judicial independence

Judicial independence is not absolute. There is a requirement for "good behavior." The legislature has different means of regulating the courts. There are a variety of things to balance.

Given that, it is reasonable as a whole to set forth a term limit, perhaps of 18 years, including because historically judges often did not have such long terms and judges now have much more power, and so on. A look at practice in other nations reaffirms that limited tenure can be balanced with independence.

I'm not going to respond in depth to the attorney general component except to say I'm open to the idea that the AG should be more independent of the president. Many state AGs are & the current politicization of the Justice Department is troubling.