The Volokh Conspiracy

Mostly law professors | Sometimes contrarian | Often libertarian | Always independent

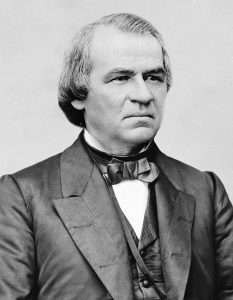

Today in Supreme Court History: February 21, 1868

2/21/1868: President Johnson orders Secretary of War Edwin Stanton removed from office. In Myers v. U.S. (1926), the Supreme Court found that Johnson's actions were lawful.

Editor's Note: We invite comments and request that they be civil and on-topic. We do not moderate or assume any responsibility for comments, which are owned by the readers who post them. Comments do not represent the views of Reason.com or Reason Foundation. We reserve the right to delete any comment for any reason at any time. Comments may only be edited within 5 minutes of posting. Report abuses.

Please to post comments

How very interesting Myers was decided today.

Myers was decided October 25, 1926. Professor Blackman noted that on February 21, 1868 President Andrew Johnson gave the order for Secretary of War Edwin Stanton to be removed from office.

Digital Realty Trust, Inc. v. Somers, 583 U.S. 149 (decided February 21, 2018): whistleblower statute did not allow damages for retaliatory termination where employee had reported securities laws violations to senior management but not to the SEC

Class v. United States, 583 U.S. 174 (decided February 21, 2018): defendant pleading guilty can still appeal on grounds that statute under which he was charged is unconstitutional (carrying a gun on U.S. Capitol grounds, 40 U.S.C. §5104(e)(1), which he argued violated Second Amendment; the D.C. Circuit ended up rejecting this argument, 930 F.3d 460, but that was before New York State Rifle & Piston Ass’n v. Bruen, 2022, where the Court, disagreeing with both parties in front of it, held that cases such as Class applied too lax a standard of scrutiny, see Bruen fn.4)

Ministry of Defense of Iran v. Elahi, 546 U.S. 450 (decided February 21, 2006): Elahi, an Iranian citizen, sued the Islamic Republic of Iran (he claimed it murdered his brother) in federal court and got a default judgment. Meanwhile Iran’s Ministry of Defense won an arbitration award in Switzerland on an unrelated matter and went to federal court to confirm it, thus locating the award in the U.S. Here Elahi moves to attach it so as to satisfy his judgment. The Foreign Sovereign Immunities Act does not apply to commercial activities of an “agent or instrumentality” of a foreign state but the Court, relying on the opinion of the Solicitor General, holds that the Ministry of Defense is not an “agent or instrumentality” but part of the foreign state itself. Therefore the Ministry of Defense has immunity and the petition for attachment is dismissed.

Gonzalez v. O Centro Espirita Beneficente Uniao do Vegetal, 546 U.S. 418 (decided February 21, 2006): Religious Freedom Restoration Act prevented prosecution of religious sect for using hallucinogenic tea in their services

Blanchard v. Bergeron, 489 U.S. 87 (decided February 21, 1989): 40% (!!) contingency fee arrangement between plaintiff and his lawyer did not place ceiling on amount of fees recovered from losing side in §1983 action (I can personally testify to the ridiculous over-lawyering by plaintiff counsel in §1983 actions, knowing they can recover for it or at least use it as leverage for settlement)

McElrath v. Georgia, 601 U.S. 87 (decided February 21, 2024): “not guilty by reason of insanity” verdict precluded retrial of malice-murder charge on Double Jeopardy grounds even though state court had struck it as logically inconsistent along with same jury’s “guilty but mentally ill” verdict on aggravated assault charge arising from same conduct

Digital Realty Trust, Inc. v. Somers, 583 U.S. 149 (decided February 21, 2018): whistleblower statute did not allow damages for retaliatory termination where employee had reported securities laws violations to senior management but not to the SEC

Companies to all employees: If you want whistleblower protection, make sure you report us to the government!

I think they didn’t want the statute to reach into internal business affairs — might run afoul of the Business Judgment Rule and raise privacy or interstate commerce concerns.

McElrath v. Georgia, 601 U.S. 87 (decided February 21, 2024): “not guilty by reason of insanity” verdict precluded retrial of malice-murder charge on Double Jeopardy grounds even though state court had struck it as logically inconsistent along with same jury’s “guilty but mentally ill” verdict on aggravated assault charge arising from same conduct

We correctly hold that an acquittal is sacrosanct, even if the judge or jury made a clear error regarding the verdict. Is the US the only country with this rule? I've heard and read countless times of other free nations successfully appealing acquittals.

Yes, it's rare. Many countries do not use the American jury system, which is a prerequisite for understanding the double-jeopardy concept. In civil-law countries (Japan included), appellate courts can examine additional evidence, and acquittals would come with a judicial opinion, not just a checkmark on a paper.

In those countries, a single case (including appeals) constitutes a single jeopardy.

Note though that the double jeopardy rule does apply to bench trials also.

Provided there is jeopardy in the first place, of course, e.g., my favourite instance, People v Aleman

If not unique, it is at least highly unusual; indeed, many individual states didn’t even apply things that way until the Supreme Court said they had to in 1969.

Some of the cases from around the turn of the 20th century do suggest that the doctrine seems to have snuck in as a misunderstanding of the common law rule, and I think Oliver Wendell Holmes makes a decent case that it’s neither practically nor doctrinally very compelling in his dissent in Kepner v. United States, 195 U.S. 100, 134-137 (1904). But it’s certainly not going anywhere any time soon.

The job of a defense attorney is not to seek justice for his client, but to prevent a conviction.

Not only is that not accurate (in many cases, a conviction is assured, and the attorney’s role is mitigating the consequences of that), but it also doesn’t seem to have much to do with my comment, or SMP0328’s.

The old joke of the junior attorney sent to try a case in the boondocks, after the trial sends a telegram back to HQ, "JUSTICE WINS" and gets the response, "APPEAL"

That was pretty much my point.

You can hear Roberts say "Gonzalez v. O Centro Espirita Beneficente Uniao do Vegetal" with some verve, amusing Ginsburg, at Oyez.com.

It only took them about half a dozen decades to decide the question.

Call it Stanton's Executor.

The Supreme Court decided three cases today, two unanimous (false claims issue & right to bring Holocaust lawsuit against Hungary in U.S. courts denied), one 5-4 (Kavanaugh for Roberts & the liberals) summarized by Chris Geidner:

"In a 5-4 win for unemployed workers, the Supreme Court allows their lawsuit to proceed alleging that Alabama is illegally delaying their benefits."

It has federalism implications which helps explain the vote split.

In Williams v. Reed (Alabama unemployment), Thomas seems to disagree with what I thought was settled law. A state court of general jurisdiction must accept claims based on federal law. A court of limited jurisdiction need not. Plaintiffs sued under section 1983 in state court. Thomas would let Alabama say "all claims are welcome in circuit court except section 1983 claims which have not been administratively exhausted." Policy arguments aside, isn't Thomas clearly on the wrong side of Supreme Court precedent? The courts called circuit courts are ordinarily the state courts of general jurisdiction.

Part I of Thomas’s opinion is entirely dedicated to explaining why he thinks those cases are wrong. This is presumably why the remaining three justices joined only Part II.

Policy arguments aside, isn't Thomas clearly on the wrong side of Supreme Court precedent?

Thomas has been clear throughout his time on SCOTUS that he couldn't care less about precedent he dislikes. To him, stare decisis is a dirty word. That's why many times, like in this case, he will stand alone while railing against decisions he dislikes.

As I understand it:

Alabama: "You can't go to court until you've exhausted your claims, and so if we're doing nothing to move your claim forward such that it can be exhausted, you can't go to court to get us to move it and you're SOL."

SC: "Nope"

Thomas: "Yup"

President Johnson in part argued that he fired Stanton to test the law in court. So, he thought the courts should have a key role in deciding who a president can fire. Sounds familiar.

The reach of Myers (not misspelled this time) was later limited. It also was a 6-3 opinion with the dissenters including Brandeis and Holmes. This is far from surprising since originally the rules regarding the power to remove split the first Congress around four ways and Hamilton changed his position from the one he outlined in the Federalist Papers.

I agree with Kagan in her Seila Law dissent that this is "[t]he best view is that the First Congress 'was deeply divided' on the president's removal power" and it is not the job of the courts to artificially pick and choose one path.

If the courts are to be involved, just what is their job?

Say what the law is, so that the Executive knows what it can and cannot do. You will of course agree that it would be a violation of Separation of Powers if the Executive took upon itself to exercise judicial, not merely Executive, power.

At his impeachment trial, Johnson did argue the Tenure of Office Act was unconstitutional, but he also argued that, even if it was constitutional, he did not violate it at all. The Act provided that Cabinet officers "shall hold their offices respectively for and during the term of the President by whom they may have been appointed and for one month thereafter, subject to removal by and with the advice and consent of the Senate." Secretary of War Stanton had been appointed by President Lincoln, not Johnson, and Lincoln's "term", argued Johnson, had ended when he died.

That the First Congress "was highly divided" on a question is not a legal argument. People may be "highly divided" on any number of legal questions, but the courts must still decide them. I believe common sense dictates that a President should not have to be saddled with a principal officer, one entrusted with carrying out his policies, who is his avowed opponent. Would someone seriously argue that Congress could grant life tenure to a Cabinet officer? How about just 10 years?

The FBI director has a statutory term of 10 years. Should a Democrat succeed Donal Trump in 2029, he will very likely fire the recently appointed Director, Kash Patel. Should that happen, I suspect most of the individuals screaming about Trump's dismissal of Director Wray will be silent. I, for one, can promise you my position will not change. I do not believe Trump should be involuntarily saddled with Biden appointees, nor do I believe a Trump successor should be saddled with Trump appointees.

Nixon played L. Patrick Gray like a cheap violin. It is dangerous to democracy to allow a President to use the law enforcement powers of the federal government to attack his political adversaries. That is why Congress established the 10-year term. Presidents have accepted that rule (don’t you think Bill Clinton would have loved to fire Louis Freeh?) until Trump smashed it.

It's odd you should mention Clinton, as it was he who fired FBI Director Sessions after Sessions refused to resign. As to why Clinton didn't fire Freeh (his appointee), he likely felt it would be too much to fire two directors, particularly one he himself had appointed, which, I suspect, is the same reason Trump did not fire Wray in his first term.

The impetus for the ten-year term was to prevent another Hoover. In other words, it was merely viewed as a maximum length of tenure. But if you like "independent" (i.e., "unaccountable") law enforcement, then you have the Hoover model to guide you. Though, let's face it, for many on the Left today, a left-wing Hoover is exactly what they want. I always felt Comey aspired to be another Hoover, but lacked the intelligence or gravitas to pull it off.

Sessions was caught in a ethical violations. That's why he was sacked, after he refused to resign. His work in the job had been praised by even by Democrats.

The 10 years was not in any way viewed as a maximum term; if you think that, you haven't read the statute: "the term of service of the Director of the Federal Bureau of Investigation shall be ten years. A Director may not serve more than one ten-year term." As to why a 10-year term necessarily leads to a 48-year Hooverian term, you've lost me.

You mean the statute, which you quoted, saying that 10 years is the maximum term?

He meant that the term could be anything up to 10 years. He was wrong.

"Ethical violations" that happened to come to light just as a new President was assuming office. Gee, they couldn't possibly have been pretextual at all. But, yes, I was certain that was the answer you would give. Clinton had good reasons; Trump had ignoble ones. I guess that should be the test of constitutionality of Congressional restrictions on a President's removal powers.

As for my conclusion that the ten years was viewed by Congress as a maximum, I refer you to my below citation from the Congressional Research service in 2014. As to whether a Director may serve beyond the ten years, contra the text you have so ably reproduced, the Senate apparently decided he could, given its extension of Mueller's term in 2011, as requested by President Obama, as I recall. Another president "smashing" those sacred rules.

There was little opposition to Obama’s request. It was not a corrupt act, like Trump’s was.

"Though, let's face it, for many on the Left today, a left-wing Hoover is exactly what they want."

That should be "the Left" (TM), a stereotypical, often fantastically large and kneejerk group that is a result of some transference.

It was not "merely" seen as a maximum tenure. There was also a general belief that the ten-year tenure would provide some independence and removal would be used warily.

It was a compromise between a Hoover and some tool for the president. They would not be "unaccountable" which is not the same as "independent." There would be a middle ground.

https://news.law.fordham.edu/blog/2017/05/18/why-did-congress-set-a-ten-year-term-for-the-fbi-director/

Congressional Research Service, FBI Director: Duration and Tenure 15 (2014)

That the First Congress "was highly divided" on a question is not a legal argument. People may be "highly divided" on any number of legal questions, but the courts must still decide them.

Okay?

The courts should decide that the question is not settled by the Constitution in various respects. It is a political question that divided Congress and should be broadly left to them to decide.

What you think is "common sense" is duly noted. The First Congress split on what "common sense" dictated and this is about much more than Cabinet officers.

Also, the very concept of a Cabinet was a creation of the Washington Administration as discussed by Lindsay M. Chervinsky. The rules are not patently obvious. For instance, John Adams felt obligated to keep Washington's Cabinet in the beginning.

William Wirt was Attorney General from 1817-29. Not likely today.

The exact scope of the role of the secretary of treasury also was not clear early on. Some thought Hamilton would serve almost like a prime minister. As someone involved in economic policy, he had a closer relationship with Congress than others.

The exact contours of appointments and removals developed over time. The courts have some role in applying the rules but the Constitution as Kagan notes provides Congress much discretion.

You'll have to forgive me, as you are clearly more emotional about this issue than I am (though I imagine this would be true of most issues). Rather obviously, I am merely relating my opinion, which happens to be in accord with nearly a century of legal precedent, but I have certainly disagreed with such precedent in the past. I hardly begrudge anyone for having a different opinion.

I recall a recent discussion we had about "neutral principles" and the modern leftists' seeming inability to apply them. I approach this issue as, "What may the President do?", whereas they often approach it as "What may President Trump do?" or "What may President Biden do?" to which they reach opposing conclusions. My opinion on Article II removal powers will not change when a Democrat assumes the presidency, though I suspect, many of the vociferous leftists here and elsewhere will assume a different view, as one of the political party's mottos increasingly seems to be, "It's (D)ifferent when we do it."