The Volokh Conspiracy

Mostly law professors | Sometimes contrarian | Often libertarian | Always independent

Today in Supreme Court History: December 21, 1922

Editor's Note: We invite comments and request that they be civil and on-topic. We do not moderate or assume any responsibility for comments, which are owned by the readers who post them. Comments do not represent the views of Reason.com or Reason Foundation. We reserve the right to delete any comment for any reason at any time. Comments may only be edited within 5 minutes of posting. Report abuses.

Please to post comments

Oregon v. Mitchell, 400 U.S. 112 (decided December 21, 1970): original jurisdiction case; Congress can set voting age requirements for federal elections but not state or local elections (quickly abrogated by Twenty-Sixth Amendment which set national voting age of 18)

Baltimore City Dept. of Social Services v. Bouknight, 488 U.S. 1301 (decided December 21, 1988): Granting stay of Court of Appeals order holding that mother properly invoked self-incrimination privilege when refusing to answer questions from DSS about whereabouts of son (in other words, the trial court’s holding of contempt was back in effect) (this was not a sympathetic contemnor; there was “hard evidence” of mother’s previous physical abuse of child and she had stopped attending parenting classes and appearing for DSS appointments) (the Court eventually affirmed the finding of contempt, 493 U.S. 549, 1990). She was finally released in 1995 after seven years in jail. The judge ordered no contact with her son (fortunately they had found him) unless cleared by a psychiatrist. This is from the story of her release, from the Baltimore Sun: “Ms. Bouknight’s attorneys insisted their client had been victimized for trying to cooperate with police to find Maurice. Every time she started to help again, other lawyers in their case would withdraw their support for her release on the grounds that her cooperation meant that keeping her jailed was having some helpful effect.” ??

Williams v. North Carolina, 317 U.S. 287 (decided December 21, 1942): North Carolina must give “full faith and credit” (art. IV, §1) to Nevada divorces; dismisses bigamy prosecution (at which a jury evaluated proper service of Nevada divorce proceedings and “bona fides” of couple’s residence in Nevada)

The 26th Amendment says "The right of citizens of the United States, who are eighteen years of age or older, to vote shall not be denied or abridged by the United States or by any State on account of age."

I don't see that mandating 18 being the age of majority.

The main impetus of the 26A was Vietnam. A large majority of our dead soldiers never got to see their 21st birthday.

My quick Google says that the average age of soldiers who died in Vietnam was 22.8. There would have been a few soldiers up to their forties so it's likely that the median was a little lower (the youngest were only 16 or so) and it seems just barely possible that the majority were under 21, i.e., the median was 20.8 or something. But that's statistically unlikely and it's extremely unlikely that there could have been a 'large' majority under 21. Perhaps just "[Many] of our dead..." would be more accurate.

Looked it up just now. It was 61%.

Interesting. I have also found another page which gives that number, but gives an even higher number for the averages. I'd be curious to see the distribution of ages that causes such a large difference between the median and mean. The only queryable database I could find gave only the date of death without the birth date. I expect that somewhere there is an electronic database (or just an Excel spreadsheet) with both (or with the age at death), but I haven't been able to find it.

Thanks for the info...

I see some sites (really just other sites copying one, it looks like) that gives the figure, but that also includes some other statistics that would require a pretty unusual data set to work out. I see some other sites with different but not wildly inconsistent numbers, but whose data can’t possibly be right (i.e. the numbers don’t add up correctly). So absent a more authoritative source, I’d be a little hesitant to endorse that figure unreservedly.

None of which, of course, detracts from your basic point: that the example many young people risking and losing their lives in military service played a role in developing a sense that people of that age should have a political voice.

Who said it did?

18 year old shows up to vote. State says, "You're too young!" Denial or abridgement of what is now an enumerated right, the right to vote at 18.

Now if you mean more general purposes than just voting, I don't know.

I discussed the ratification of the ERA.

The exact rules for ratification have received a lot of discussion. Balkanization Blog had some discussions about this subject in the past. Me, someone who comments here regularly, and others had a lot to say. Ultimately, "the rules" are just that -- open to debate.

Explicit and Authentic Acts by David E. Kyvig in an interesting book on amending the Constitution. It was written in the mid-1990s, so was able to cover all twenty-seven amendments, including the failed ratification of the ERA.

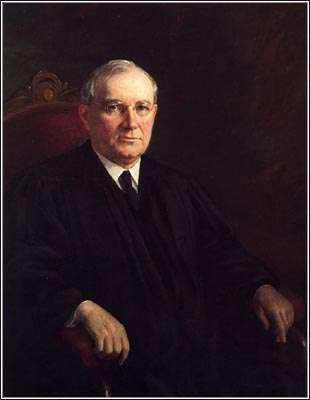

A Supreme Court Justice Is Appointed has been referenced before. It is an interesting account of the confirmation of Pierce Butler. It has a few chapters that go into the theoretical academic weeds, so to speak, and some might want to skip them.

Constitutional amendment is supposed to be an open and tranparent process, with The People making a deliberate, conscious decision to change the rules of how government behaves.

There is no room for weasely debate and little trickies to get your way.

If you say 7 years, and states vote on that, and you rescind or extend the 7, sorry, weasels, game over.

If a state later rescinds its approval before the magic number, again, sorry, game over. The People shall not be dragged kicking and screaming into something they don't want anymore because motivated power mongers weasel their weasel ways. Moreover, although the above is more than sufficient to collapse the house of cards, note that at no point was there an actual 3/4 approving it.

Oh, you say, say, Idaho approved it? Let's ask Idaho! "Fuck no!!"

The weasels, being weasels, fancy they can put the entire nation into a headlock and force them through the door. And think themselves clever for it.

Step away from the Constitution, you freakin' weasels.

Iiirc, Butler was the lone dissenter on Buck v Bell, though he didn’t write an opinion as to why (perhaps the sterilization offended his Catholic beliefs but he could not articulate a legal grounds of dissent within the jurisprudence of his day?).

Justice Butler had a few "right to privacy" type opinions. His conservative views had some libertarian aspects.

His first dissent involved the destruction of liquor which he argued was innocently owned (Samuels v. McCurdy.)

He was one of the dissenters (writing a separate dissent) in Olmstead v. U.S. (wiretapping) and wrote Sinclair v. United States, which noted:

It has always been recognized in this country, and it is well to remember, that few if any of the rights of the people guarded by fundamental law are of greater importance to their happiness and safety than the right to be exempt from all unauthorized, arbitrary or unreasonable inquiries and disclosures in respect of their personal and private affairs.

Another path in Buck v. Bell was possible. Multiple lower court opinions struck down such laws on multiple grounds. The case had serious due process concerns, for instance, and Justice Butler as a lawyer and prosecutor showed respect for due process.

One or more of the other justices also were somewhat concerned about the case. They weren't all as sure about it as Holmes. Taft asked Holmes to tone down his original draft.

Justice Holmes thought Butler's dissent was a result of his Catholicism, which very well might have been an influence. Still, it is far from clear that is the only reason.

Butler often restrained from dissenting even when he didn't like an opinion & tried to write narrow opinions. Too bad he did not write a dissent here.

I suspect your assessment is correct. That was certainly what Holmes thought. During conference on the case, Holmes supposedly remarked, "Butler knows this is good law. I wonder if he will have the courage to vote with us in spite of his religion."

Most of the criticism of Buck v. Bell nowadays falls on Holmes, the author of the opinion, but Chief Justice Taft, who assigned the opinion to Holmes, was also an advocate for eugenics. He had been the chairman of the Life Extension Institution, a non-profit that advocated, among other things, the segregation and sterilization of "defectives".

A great many of the educated and "right-minded" people of the day were enthusiastic about eugenics. It was "scientific". The idea generally fell out of favor after the Germans took it and really ran with it.

Eugenics works with animals so there seemed no reason to suppose it would not work with humans. This is, of course, betrays an incomplete understanding.

I have never been comfortable with Buck v Bell; I find the decision utterly repellant. I do not understand why SCOTUS has not explicitly over-ruled it, esp during the pandemic.

Under what circumstances would the court have had an occasion to overrule it?

They overruled Korematsu by dicta in Trump v. Hawaii, a case that had very little similar issues at play.

They said it was no longer good law but the rationale of the Korematsu case easily supports that result.

The dissent expressly argued that the majority’s reasoning was equivalent to Korematsu, inviting the majority opinion to discuss it. No one (as far as I know) seriously argued that any COVID measures were comparable to Buck v. Bell, so there would have been no real occasion to bring it up (much less “overrule” it).

To Commenter_XY’s point, individual justices haven’t been shy about voicing their thoughts on the case. See, e.g., Box v. Planned Parenthood, 587 U.S. 490, 499-500 (2019) (Thomas, J., dissenting); Tennessee v. Lane, 541 U.S. 539, 534-535 (2004) (Souter, J., concurring). But until a state actually follows through on trying to forcibly sterilize someone in broadly similar circumstances, there’s not much occasion for the court to jettison it. To put it differently: the Buck v. Bell principle has been so roundly rejected by the American people that it’s not likely that a case will arise requiring the Supreme Court to reject it explicitly.

One case that was frequently referenced during the COVID-vaccine debates was Jacobson v. Massachusetts, 197 U.S. 11 (1905), in which the Court upheld Massachusetts' smallpox vaccine mandate.

People often remember the most infamous sentence in Holmes' Buck v. Bell opinion, but tend to forget the sentence that preceded it:

274 U.S. 200, 207 (1927)

That would have seemed to provide a rather fitting opportunity, and certainly one less awkward than Trump v. Hawaii provided to overrule Korematsu/

Wasn't Jacobson only fined $10 and not actually required to take the shot? That makes it seem quite dissimilar, especially in hindsight after seeing thousands of people keel over from "died suddenly." Ultimately those responsible, including the conflicted Dr. Fauci, are going to have to pay the price under the Nuremberg Code. I expect the Trump DHHS very soon to open the door to begin this process.

Jewish space aliens have nothing to do with this.

1) The Nuremberg Code is not a law.

2) The Nuremberg Code was about experiments, not treatment. (And no, saying that a treatment is experimental is not the same thing.)

3) Nobody, let alone thousands, keeled over and died suddenly from covid vaccination.

4) What role do you think HHS would have in criminal punishments?

Other than that, great comment!

I’m not sure I see how. Holding that the Jacobson principle wasn’t sufficient to justify a COVID restriction might implicitly overrule Buck v. Bell, but I can’t see how overruling the latter would shed much light on the propriety of the former.

Oh, I'm sure you'd be clever enough to think of something if you had to.

Skinner v. Oklahoma (equal protection argument) limited its scope and later opinions put more teeth into restraints of nonconsensual medical treatment.

Skinner v. Oklahoma ex rel. Williamson, 316 U.S. 535 (1942), was not grounded in limitations imposed on states by the Due Process Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment. Justice Douglas, a New Dealer, was loath to invoke Substantive Due Process, likely because he remembered the Lochner era of the Supreme Court. The decision did not hold that compelled vasectomy or salpingectomy exceed the police power of the states, but ruled that the habitual criminal statute at issue violated Equal Protection.

Even in Griswold v. Connecticut, 381 U.S. 479 (1965), Douglas's majority opinion did not rely expressly on Substantive Due Process (except to note that Lochner is no longer good law, id., at 481-482).

Skinner and Griswold did later come to be regarded as a Substantive Due Process case. See, Washington v. Glucksberg, 521 U.S. 702, 720 (1997).

Yes, as noted, Skinner was decided using an equal protection argument. Stone relied on due process. Jackson relied on both due process and equal protection.

Buck v. Bell ridiculed an equal protection argument as "the usual last resort of constitutional arguments."

Skinner cited that language but then said that the law involved "basic civil rights of man" including marriage and procreation. Of course, so did the earlier law upheld by Holmes.

The opinion (as noted by Victoria Nourse's interesting book on the case) was a turning point in the understanding of liberty and equal protection. Douglas might not have wished to recognize it as an exercise of substantive due process but ultimately equality and substantive due process were joined. See, e.g., the same-sex marriage cases.

Once you start using fundamental rights language, such laws would be put to a higher degree of scrutiny. Buck v. Bell might never have been formally overruled but it is questionable how much it functionally survives.

IIRC, Butler (or his family) destroyed his papers, and he never cultivated a following of sycophantic law professors. Unsurprisingly, Butler's historical reputation is less than Oliver Wendell Holmes'.

One thing Butler and Holmes had in common: Neither were progressives or liberals.