The Volokh Conspiracy

Mostly law professors | Sometimes contrarian | Often libertarian | Always independent

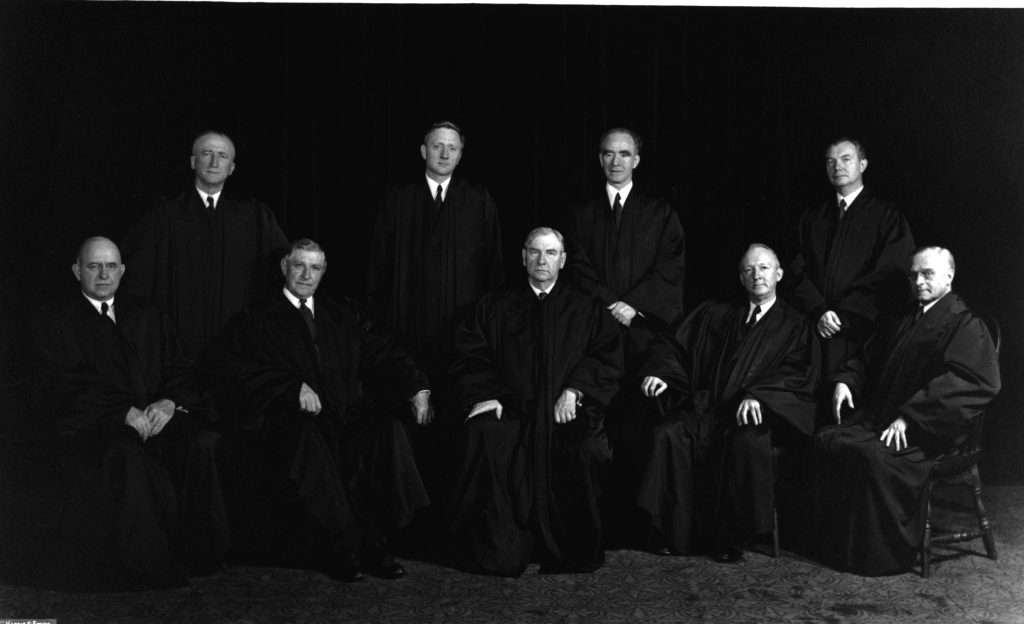

Today in Supreme Court History: November 9, 1942

11/9/1942: Wickard v. Filburn decided.

Editor's Note: We invite comments and request that they be civil and on-topic. We do not moderate or assume any responsibility for comments, which are owned by the readers who post them. Comments do not represent the views of Reason.com or Reason Foundation. We reserve the right to delete any comment for any reason at any time. Comments may only be edited within 5 minutes of posting. Report abuses.

Please to post comments

Harris v. Forklift Systems, Inc., 510 U.S. 17 (decided November 9, 1993): Title VII claimant (“abusive work environment”) need not show that her psychological well-being was “seriously affected”; totality of circumstances but still must be “objectively” abusive (ALJ found supervisor made frequent gender insults, sexual innuendos, “You’re a woman, what do you know”, “We need a man as the rental manager”, “you’re a dumb ass woman”, suggested “we go to the Holiday Inn”, asked her to get coins from his front pocket, etc., etc.)

Wickard v. Fillburn, 317 U.S. 111 (decided November 9, 1942): Congress can regulate amount of wheat farmer grows for his own consumption because it takes away from what he might sell in interstate commerce (my Con Law professor said this case was “the final nail in the coffin” of the Restricted Commerce Clause era, but he was saying this in 1991; the coffin has since popped open)

Ex Parte U.S. Joins, 191 U.S. 93 (decided November 9, 1903): the Court has no power to annul decisions of “Citizenship Court” set up by Congress to (against the wishes of Oklahoma tribes) break up their communal land and sell to individuals; the court had already ceased to exist, having performed its only legislated function

Wickard v. Fillburn first deals with a mostly forgotten discussion answering the opinion below finding fault regarding how the U.S. Secretary of Agriculture campaigned for the measure.

The second section of the opinion provides a broad meaning of what Congress can regulate per the Commerce Clause. The outer limits are somewhat beside the point here given the regulation of the wheat market is not that hard of a call.

Some argue Gonzales v. Raich was an overreach. The opinion suggests otherwise. A large interstate and international marijuana market was involved.

(Many justices applied constitutional principles in ways contrary to their personal policy beliefs. Scalia and Kennedy's votes perhaps are more open to claims of being unprincipled.)

The policy questions are different. Also, the Constitution gives Congress with representatives from the states the power to weigh and balance what merits usage of its power.

I think a liberty interest is a better argument if one is not open under current SCOTUS jurisprudence. Compare, for instance, an article by Justice Tom Clark in the 1970s that argued personal usage of marijuana was likely protected under a right to privacy.

Is there a "right to privacy" in the Constitution (not withstanding the 4th Amendment) or in any law?

Should it be codified and if so how should it be defined.

Many states have explicit rights to privacy in their constitutions. No one agrees on what that meansc and in practice it ends up working out as a license for judges to rewrite laws they don’t like.

See this post for a discussion.

https://reason.com/volokh/2018/11/12/nh-constitution-now-protects-right-to-li/

The First Amendment splits people into many camps and the net result is that the courts have a large say on what they “like.”

I don’t think it is a hard call that Congress can regulate the wheat market.

It also shouldn’t have been a hard call was that Roscoe Filburn was not participating in the wheat market by growing his own wheat and feeding it to his own cows.

That decision would be very unlikely to be issued today.

Congress was regulating the wheat market and his wheat was part of the wheat market as a whole.

His cows were also part of the market. One article on the case (from a chapter from "Constitutional Law Stories" on the case) noted:

Roscoe Filburn raised dairy cattle and poultry. His family welcomed "75 customers ... every day for milk and eggs."

Filburn's wheat was not just for his personal use. Not only was it used for cattle/poultry that he raised for profit, he sold some of it.

He was a market participant.

Congress had the power to regulate his wheat production. The case should be decided the same way today.

The case could have been decided against Filburn on narrower grounds?

Were any of his customers out of state?

The original claim, to keep track, was that he was "not participating in the wheat market."

I don't see a breakdown in the article of his customers.

The overall national nature of the wheat market, including the commercial flow of products used by the wheat, makes the question somewhat trivia.

Being a part of the market isn't what the Commerce Clause requires for federal regulation. *Interstate* commerce is. This is the most far-reachingly wrong of all the bad SCOTUS decisions during the New Deal. And it's the one on which the Federalist Papers have the most to teach the Court, if the Court ever wants its legitimacy back.

It also shouldn’t have been a hard call was that Roscoe Filburn was not participating in the wheat market by growing his own wheat and feeding it to his own cows.

Except for the inconvenient fact that he was participating in the wheat market.

Yeah, he was participating in the market even when he was not selling the wheat he grew on his farm, says the common man sarcastically.

But if we assume that it is never marketed, it supplies a need of the man who grew it which would otherwise be reflected by purchases in the open market. Home-grown wheat in this sense competes with wheat in commerce, says the court.

So you admit the wheat farmer Filburn grew would not be in commerce, let alone interstate commerce, unless actually marketed, but you still insist the interstate commerce clause reaches his activity -replies the common man.

If it competes with wheat in commerce, then it affects the market and so can be regulated, says the court (in so many words).

So if Filburn and other farmers had grown corn instead of wheat and fed that corn to their livestock, they also would have been competing with wheat in the market. Or if they had decided to slaughter their cows rather than be subject to the AAA, that also would have a substantial effect in defeating and obstructing its purpose to stimulate trade therein at increased prices. Pray tell, is there any end to the reach of the Commerce Clause?

Why do you ask? Says the Court.

Because "aggregate effects" when combined with the "substantial effects" doctrine creates an extension of the reach of the commerce clause that has no bounds, even our individual economic decisions are subject to regulation under such an expansive view of the reach of the commerce clause, says the common man.

In fact, economic and financial decisions are activity that is commercial and economic in nature, so of course such decisions fall squarely within the reach of the commerce clause, said 4 members of the Court.

But why not all 9 members of the court? Asks the common man.

Explain, says the Court.

If this aggregate effects doctrine is true, then surely all 9 members of the court should have embraced Justice Ginsberg's reasoning in NFIB. Why didn't they? Asks the common man.

JoeFromTheBronx pointed out that he grew other wheat on the same farm that he sold to others.

Perhaps the judgment could have been justified on the facts.

I still disagree with the reasoning.

My heretical opinion: both Wickard and Raich are not only right, but obviously right, and the constitutional design that makes them right was a very good decision.

Why heretical?

Because those cases are the bêtes noires of most of my conservative and libertarian fellow travelers.

How about NFIB, was Ginsberg's opinion also obviously right?

From PPACA:

EFFECTS ON THE NATIONAL ECONOMY AND INTERSTATE

COMMERCE.—The effects described in this paragraph are the following: (A) The requirement regulates activity that is commercial and economic in nature: economic and financial decisions about how and when health care is paid for, and when health insurance is purchased.

Ginsberg opinion (NFIB):

First, Congress has the power to regulate economic activities “that substantially affect interstate commerce.” Gonzales v. Raich, 545 U. S. 1, 17 (2005). This capacious power extends even to local activities that, viewed in the aggregate, have a substantial impact on interstate commerce. See ibid. See also Wickard, 317 U. S., at 125 (“[E]ven if appellee’s activity be local and though it may not be regarded as commerce, it may still, whatever its nature, be reached by Congress if it exerts a substantial economic effect on interstate commerce.”

"The outer limits are somewhat beside the point here given the regulation of the wheat market is not that hard of a call."

Similarly, it's not a hard call that one has no need to shade one's eyes looking East in the morning, given that the Sun rises in the West...

The problem here is that the interstate commerce clause is not a grant of power to regulate 'markets'.

It's a grant of power to regulate commerce across specified boundaries, and ONLY commerce across those boundaries. Not commerce in general, not 'markets', not anything that hypothetically or actually might have an effect on such commerce.

Just that subset of commerce, and nothing more.

In the running for alltime stupid and unjust ruling is Wickard v. Filburn.

Would be cool to have a plebiscite on it. I bet a landslide would oppose it. It has 3 horrendous faults to it.

1) Everything you do affects something, so your entire life is subject to this ruling.

2) Even if it were true that your private use has public repercussions, did we fight for freedom only if everyting turns out wondeful? Maybe it will all turn out badly but let's ensure that no matter how it turns out we allowed for a good outcome. Which would be "I can grow some damn crops for my animals"

3) THis is the crucial reasoning that leads to things like negative interest rates at banks!! YES , it has been done already

The Swedish experience with negative central bank rates in 2015-2019

Lars Jonung Fredrik Andersson / 8 May 2020

Negative interest rates were once seen as impossible outside the realm of economic theory. However, recently several central banks have imposed such rates, with prominent economists supporting this move. This column investigates the actual effects of negative interest rates, taking evidence from the Swedish experience during 2015-2019. It is evident that the policy’s effect on the inflation rate was modest, and that it contributed to increased financial vulnerabilities. The lesson from the experiment is clear: Do not do it again.

https://cepr.org/voxeu/columns/dont-do-it-again-swedish-experience-negative-central-bank-rates-2015-2019

TELL ME WHERE I AM WRONG ON THIS