The Volokh Conspiracy

Mostly law professors | Sometimes contrarian | Often libertarian | Always independent

MSNBC Pundit's Tweet Accusing Lawyer of "Coach[ing a Witness] to Lie" Is a Potentially Defamatory Factual Assertion, Not an Opinion

Plaintiff (Stefan Passantino, Cassidy Hutchinson's former lawyer) may thus eventually prevail, if the claim is shown to be false, and if the defendant is shown to have spoken with "actual malice" (if plaintiff is a public figure) or negligently (if plaintiff is a private figure).

From Judge Loren L. AliKhan's decision yesterday in Passantino v. Weissmann (D.D.C.):

The following factual allegations drawn from Mr. Passantino's complaint, are accepted as true for the purpose of evaluating the motion before the court. Mr. Passantino has been a lawyer for more than thirty years. In 2017 and 2018, he served as a senior lawyer in the Trump administration. Since then, he has been in private practice.

Following the attack on the U.S. Capitol on January 6, 2021, the House of Representatives established a Select Committee to investigate what had happened. As part of its investigation, the Select Committee interviewed numerous witnesses, including Cassidy Hutchinson, a former special assistant to President Trump who had been serving under the direction of White House Chief of Staff Mark Meadows on January 6, 2021.

Mr. Passantino represented Ms. Hutchinson at her first three closed-door Select Committee depositions on February 23, March 7, and May 17, 2022. While the complaint does not specify exactly when this occurred, Ms. Hutchinson sent text messages to a friend expressing that she "d[idn]'t want to comply" with the Committee's requests. In the same conversation, however, she noted that "Stefan [Passantino] want[ed] [her] to comply."

Following the second deposition, Ms. Hutchinson felt that she had "withheld things" from the Select Committee and wanted to "go in and … elaborate … and kind of expand" on some topics. Unbeknownst to Mr. Passantino, Ms. Hutchinson asked a friend to "back channel to the committee and say that there [were] a few things that [she] want[ed] to talk about." While Ms. Hutchinson deliberately kept this from Mr. Passantino, she explained at a future deposition that, at that time, she "wasn't at a place where [she] wanted to terminate [her] attorney-client relationship with [Mr. Passantino]."

In early June 2022, after the third deposition, Ms. Hutchinson fired Mr. Passantino and retained Bill Jordan and Jody Hunt as her new counsel. She subsequently gave a fourth, televised deposition on June 28, which received substantial media coverage.

After her fourth deposition, Ms. Hutchinson sent a letter to the Select Committee stating that she intended to "waive [her] attorney-client privilege [with Mr. Passantino] in order to share information with the Committee that [was] relevant to [her] prior testimony." The Select Committee accordingly scheduled her for a fifth deposition for September 14, 2022.

At her fifth deposition, Ms. Hutchinson revealed additional details about the preparation she and Mr. Passantino had done ahead of her first Select Committee deposition. Specifically, the two had met "for a couple hours" on February 16, 2022 to discuss her upcoming testimony. When Ms. Hutchinson suggested printing out a calendar so that she could "get[] the dates right" with respect to timelines of events, Mr. Passantino said "No, no, no." He told her that the plan was "to downplay [her] role" and that "the less [she] remember[ed], the better." Id. 30:19-31:2. When Ms. Hutchinson brought up an incident that occurred inside the Presidential limousine on January 6 (which she had been told about by a colleague), Mr. Passantino said "No, no, no, no, no. We don't want to go there. We don't want to talk about that."

Mr. Passantino then told Ms. Hutchinson: "If you don't 100 percent recall something, even if you don't recall a date or somebody who may or may not have been in the room, ['I don't recall' is] an entirely fine answer, and we want you to use that response as much as you deem necessary." Id. 36:7-10. Ms. Hutchinson then asked, "if I do recall something but not every little detail, … can I still say I don't recall?" to which Mr. Passantino replied, "Yes." The morning of the first deposition, Mr. Passantino reminded Ms. Hutchinson to "[j]ust downplay [her] position," telling her that her "go-to [response was] 'I don't recall.'"

At her fifth deposition, Ms. Hutchinson discussed a line of questioning from her first deposition about the January 6 incident in the Presidential limousine. She explained that, during a break after facing repeated questions on the topic, she had told Mr. Passantino in private, "I'm f*****. I just lied." Mr. Passantino responded, "You didn't lie…. They don't know what you know, Cassidy. They don't know that you can recall some of these things. So you [sic] saying 'I don't recall' is an entirely acceptable response to this." He concluded, "You're doing exactly what you should be doing." Ms. Hutchinson explained that, in the moment, she "[felt] like [she] couldn't be forthcoming when [she] wanted to be."

Ms. Hutchinson did, however, state at her fifth deposition: "I want to make this clear to [the Select Committee]: Stefan [Passantino] never told me to lie." She recalled him saying to her: "I don't want you to perjure yourself, but 'I don't recall' isn't perjury. They don't know what you can and can't recall." She then reiterated to the Select Committee, "[H]e didn't tell me to lie. He told me not to lie."

At the Committee's final public session on December 19, 2022, a Congressmember announced that they had "obtained evidence" that "one lawyer told a witness the witness could in certain circumstances tell the Committee that she didn't recall facts when she actually did recall them."

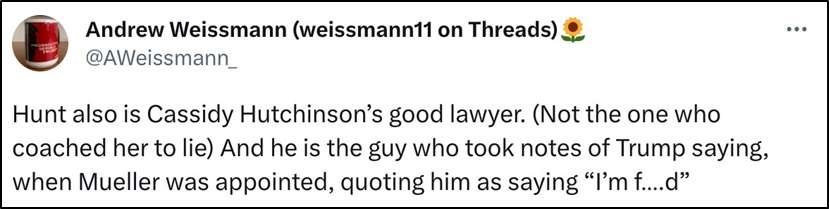

After the Committee released the transcripts from the Ms. Hutchinson's closed-door depositions, multiple news outlets claimed that the "lawyer" referred to by the Select Committee member was Mr. Passantino. On September 15, 2023, Mr. Weissmann—a former prosecutor who now serves as a "political pundit" for MSNBC—posted the following on X (formerly known as Twitter):

Mr. Weissmann made the post in response to an alert that Mr. Hunt had been subpoenaed in an unrelated case. Mr. Weissmann had approximately 320,000 followers on X at the time.

Passantino sued for defamation (and a related tort), and the court allowed the defamation claim to go forward:

Mr. Passantino alleges that Mr. Weissmann's post "deeply damaged [his] 30-year reputation and caused him to lose significant business and income." Prior to the allegations surrounding his representation of Ms. Hutchinson, Mr. Passantino had "never been accused by a client, or anyone else, of unethical or illegal behavior." …

The parties agree that this motion boils down to a core question: was Mr. Weissmann's social media post that "[Mr. Passantino] coached [a witness] to lie" a verifiably false fact, or a subjective opinion? This is not an easy inquiry, and the answer in such cases is rarely clear cut.

{For the purposes of this motion, the parties do not dispute other possible defenses to a claim for defamation, such as whether the content of Mr. Weissmann's post was substantially true. After this court's resolution of the motion to dismiss, Mr. Weissmann is free to raise any such defenses not barred by the Federal Rules. See Long v. Howard Univ.\ (D.C. Cir. 2008) ("[A] defense can be raised [as late as] at trial so long as it was properly asserted in the answer and not thereafter affirmatively waived."). The court is thus only deciding whether Mr. Weissmann's statement is nonactionable as a subjective opinion.}

The first Ollman v. Evans (D.C. Cir. 1984) (en banc) factor requires the court to determine whether the challenged statement "has a precise meaning and thus is likely to give rise to clear factual implications." The touchstone of this inquiry is whether "the average reader [could] fairly infer any specific factual content from [the statement]." As the Ollman court noted, "[a] classic example of a statement with a well-defined meaning is an accusation of a crime." The allegedly defamatory portion of the post can be distilled into: "[Mr. Passantino] coached [Ms. Hutchinson] to lie." …The definition of the verb "coach" is "to instruct, direct, or prompt." While Mr. Weissmann argues that "coached" is "indefinite," "ambiguous," and "can 'mean different things to different people at different times and in different situations,'" the court concludes that the word conveys a sufficiently precise meaning in the challenged social media post.

Readers of a statement do not isolate and parse individual words into all of their possible connotations. Mr. Weissmann wrote that Mr. Passantino "coached [a witness] to lie." In that string of text, read as a whole, the clear factual implication is that Mr. Passantino "instruct[ed], direct[ed], or prompt[ed]" Ms. Hutchinson "to lie" to the Select Committee. While it is true that general statements that someone is "spreading lies" or "is a liar" are not categorically actionable in defamation, Mr. Weissmann's post very directly claimed that Mr. Passantino had committed a specific act—encouraging or preparing a specific witness to make false statements. A reasonable reader is likely to take away a precise message from that representation.

[The second factor is the d]egree to which the statements are verifiable ….. Verifiability hinges on a deceptively difficult question: "is the statement objectively capable of proof or disproof?" In some ways, this second factor overlaps with the first because the common usage of the statement's words will determine whether the statement—as a whole—can be proven true or false.

Mr. Weissmann advances two arguments for why the statement is not verifiable. First, he reasserts his claim that "coached" is too ambiguous of a term, and that "a statement with a number of possible meanings is by its nature unverifiable." However, as discussed above, the phrase "coached her to lie" is sufficiently precise to "give rise to clear factual implications." Mr. Weissmann's ambiguity argument is therefore not persuasive.

Second, Mr. Weissmann asserts that there is no objective standard for assessing when someone has coached another to lie—at least in the absence of an explicit instruction to do so. For support, he cites various cases for the proposition that evaluating a lawyer's performance is "not susceptible of being proved true or false." Those cases are not particularly useful, however, because they primarily discuss the quality of an attorney's representation, not whether the attorney committed or engaged in a particular act. There is a difference between calling an attorney's representation "good" or "bad," on one hand, and saying that an attorney "lied" or "told the truth," on the other. The former is a subjective spectrum indicative of an opinion; the latter is a yes-or-no binary indicative of a fact….

As for the cases that do concern the act of witness preparation (rather than the quality of an attorney's representation generally), an "objective standard" is only lacking if the court assumes that the term "coach" is ambiguous. If one reasonably reads "coach" to mean "instruct, direct, or prompt" in the context of Mr. Weissmann's full social media post, then the statement is verifiable. Mr. Passantino either "coached"—that is, he "instruct[ed], direct[ed], or prompt[ed]"—Ms. Hutchinson to lie, or he didn't. The second Ollman factor thus favors Mr. Passantino.

[The third factor is the c]ontext in which the statement occurs…. This inquiry focuses on the immediate context surrounding the challenged statement. For example, a sentence asserting a seemingly factual claim takes on an entirely different meaning if situated in a satirical newspaper column….

Here, Mr. Weissmann's post contained only three sentences. It began by stating that "[Mr.] Hunt is Cassidy Hutchinson's good lawyer." Both parties agree that this is "obviously" an opinion. Then, in a parenthetical, it reads: "(Not the one who coached her to lie)." Finally, it concludes, "And [Mr. Hunt] is the guy who took notes of Trump saying, when Mueller was appointed, quoting him as saying 'I'm f….d.'" Mr. Passantino argues that the final sentence is clearly a factual assertion, and Mr. Weissmann does not contest that characterization.

Nothing about the surrounding context suggests that the reference to Mr. Passantino's "coach[ing]" Ms. Hutchinson "to lie" is facetious or sarcastic. It presents neutrally, nestled between a statement of opinion and a statement of fact. Mr. Weissmann contends that because the challenged statement follows a statement of opinion, it must also be an opinion, especially because it comes in the form of a parenthetical. Mr. Passantino takes the opposite view, arguing that the challenged statement must be a statement of fact because it is followed by a statement of fact. Given how short the full statement is, the court cannot divine much from the contested language's location to determine whether it is presented as a subjective thought or a verifiable fact….

The fourth and final Ollman factor evaluates the broader social context beyond the statement and its immediate surroundings…. Starting with X, the statement's backdrop, Mr. Weissmann asserts that it is generally considered an "informal" and "freewheeling" internet forum. [S]ome courts have held that "the fact that Defendant's allegedly defamatory statement … appeared on Twitter conveys a strong signal to a reasonable reader that [it] was Defendant's opinion."

While Mr. Weissmann is correct that X is seen by many as a free market for the exchange of subjective ideas, its use is not always one-sided. Journalists and reporters use X to post news alerts and factual content…. [I]nferring that Mr. Weissmann's statement was an opinion based solely on his use of the X platform risks overlooking "society's expectations of journalistic conduct on [X]." That is especially so when Mr. Weismann is a public figure connected to a news organization and not a private user.

This leads to Mr. Weissmann's status as a "political pundit." … Mr. Passantino asserts that Mr. Weissmann's career as a former prosecutor, his twenty-plus years of experience in the Department of Justice, and his record as an accomplished author of a book about federal prosecutions make his audience more likely to view his statements as facts. And while Mr. Weissmann currently serves as a political commentator on MSNBC, Mr. Passantino argues that that should not shield his comments from liability.

Mr. Passantino is correct that "there is no blanket immunity for statements that are 'political' in nature … [because] the fact that statements were made in a political context does not indiscriminately immunize every statement contained therein." Individuals who immerse themselves in political commentary are still capable of defaming others with verifiably false assertions. And, presumably, Mr. Weissmann does not limit his social media activity strictly to offering opinions. After all, at least one-third of the social media post in question was an expression of objective fact. Clearly, then, Mr. Weissmann's audience of followers can expect him to present some statements of fact.

At the same time, Mr. Weissmann is correct that reasonable readers know to expect subjective analysis from commentators. As a political pundit (rather than, say, a news anchor), his statements possess a general air of opinion rather than fact. "Reasonable consumers of political news and commentary understand that spokespeople are frequently (and often accurately) accused of putting a spin or gloss on the facts or taking an unnecessarily hostile stance toward the media or others." And numerous courts have held that the average reader, viewer, or listener tempers his or her expectations of hearing factual reporting in the world of punditry….

On balance, the fourth factor weighs in Mr. Weissmann's favor. But even so, the court concludes that the overall analysis of the Ollman factors suggests that his statement was not a subjective opinion.

Again, keep in mind that this merely resolves that the statement is a factual assertion; to prevail, plaintiff must still show that it's false and that defendant said it with the requisite mental state.

Editor's Note: We invite comments and request that they be civil and on-topic. We do not moderate or assume any responsibility for comments, which are owned by the readers who post them. Comments do not represent the views of Reason.com or Reason Foundation. We reserve the right to delete any comment for any reason at any time. Comments may only be edited within 5 minutes of posting. Report abuses.

Please to post comments

Seems right. Proving damages may be tricky but tear tweet seems irresponsible.

As is incentivized by a segment of media consumers. Here for the drama.

I'm surprised this is such a close question on the grounds discussed.

Twitter allows and encourages statements to be taken out of context. In a longer essay where the author summarized the factual background the word "lie" could be an opinion based on disclosed facts.

Apparently Mr. Passantino has escaped formal punishment for the Hutchinson affair. He must take a class where he will learn that third party payments for legal services require a written agreement.

Piss-poor analysis of the Ollman factors. The second factor collapses into the first; the third comes out as a wash; the fourth is in defendant's favor. But the conclusion is that this is a statement of fact? Come the fuck on.

Statements on Twitter are necessarily abbreviated, often abstracting away from context, and tend towards a kind of rhetoric designed to grab headlines. No reasonable person familiar with the internet would read the Tweet as doing other than summarizing a general impression - and opinion - of what actually happened.

This can't be the standard applied to every political commentator, especially those that are fond on commenting on the corruption in the Trump orbit (where the targets are themselves keen on abusing defamation law to shut down criticism). Does every bit of invective need to carry "allegedlys" and "arguablys," now?

This is about the deposition where Hutchinson told a bunch of implausible stories, including that Trump tried to grab the steering wheel from his driver, only to be restrained by the Secret Service.

It appears that Passantino was doing his job by coaching her to stick to the facts.

"Hutchinson detailed a conversation she had with Tony Ornato, White House deputy chief of staff for operations, and Bobby Engel, who headed Trump's security detail, at the White House after Trump's speech at the Ellipse, in which he told rallygoers that he would be marching to the Capitol with them as Congress completed its formal tally of the 2020 election results.

"I looked at Tony, and he had said, 'Did you f-ing hear what happened in the Beast?'" Hutchinson recalled, using the nickname for the presidential vehicle. "I said, 'No Tony, I just got back, what happened?' Tony proceeded to tell me that when the president got in the Beast, he was under the impression that the off-the-record movement to the Capitol was still possible, and likely to happen, but that Bobby had more information."

"So once the president had gotten into the vehicle with Bobby, he thought that they were going up to the Capitol, and when Bobby had relayed to him, 'We’re not, you don’t have the assets to do it, it’s not secure, we’re going back to the West Wing,' the president had a very strong, very angry response to that."

Hutchinson said Ornato described Trump "as being irate."

Either Ornato said it, or he didn't, but at no point was Cassidy Hutchinson claiming first hand knowledge of what had happened in the car.

And it's worth noting that at no point has Ornato straightforwardly denied that he said it (let alone doing so under oath).

And it’s worth noting that the Secret Service agents who were actually there denied Trump ever tried to grab the wheel. And they were willing to testify to that effect if called to the Jan 6 committee. Yet the committee never did so. Gee… I wonder why? Another reason why a partisan political committee is not a reliable source of anything.

https://www.theguardian.com/us-news/2022/jun/29/secret-service-agent-testify-trump-wheel-jan-6

Mr. Weissmann's post very directly claimed that Mr. Passantino had committed a specific act—encouraging or preparing a specific witness to make false statements. A reasonable reader is likely to take away a precise message from that representation.

I count myself a reasonable reader. When I read Hutchinson's book, I concluded that Passantino was practicing double talk, covering advocacy that Hutchinson should at least break an oath to tell the whole truth, with verbatim words to the contrary, to cover his own ass. I confess that I supposed that to be routine conduct by legal counsel, but not a reason to presume lawyers are always virtuous.

I thought it was remarkable testament to her forthright character that Hutchinson insisted to the committee that Passantino said not to lie. But I concluded also that she had been coached at least to distort the truth, and it seems unequivocally true that Hutchinson concluded likewise.

That it seems to me was the context of Weissman's remark. How Passantino can overcome the onus to prove actual malice on that basis remains a mystery to me. Perhaps a lawyer commenting here can clear that up for me presently. If so, I would prefer correction by someone who does not presume lawyers are always virtuous.

Saying “I don’t recall” to events she isn’t certain about is not “distorting the truth”. If she had taken that advice, we would have at least been spared all the media hype about one event that never happened (Trump supposedly assaulting a Secret Service agent)

"Ms. Hutchinson then asked, 'if I do recall something but not every little detail, … can I still say I don't recall?' to which Mr. Passantino replied, 'Yes.'"

"Mr. Passantino responded, 'You didn't lie…. They don't know what you know, Cassidy. They don't know that you can recall some of these things. So you [sic] saying 'I don't recall' is an entirely acceptable response to this.'"

Do you have kids, Mr. Rohan? If you asked one if he broke something that he did in fact break, would you think it OK if he answered "I don't recall" because he doesn't recall every little detail, or because you yourself don't know what he actually can recall? That's ludicrous, and you (should) know it.

Maybe the legal standard here is different. But *IF* the above quotes are accurate, then Passatino most certainly coached Hutchinson to lie in the ordinary, conversational sense of the word.

My kid saying yes or no to breaking a vase is different than me asking excessive details about it e.g "did the vase fall to the left or right?", "was it two or three kids that were playing around the vase?", what was the exact time the vase broke?" Answering "I don't recall" is better than trying to fill in details you aren't certain of, especially if you are recounting events you didn't even witness but just heard about second hand.

I'm more ambivalent than the other commenters.

Let me put it this way-- I think there's a lot of room to say that the standard instructions lawyers give their clients about depositions ARE a sort of permission slip to lie. I.e., they are at least encouraging witnesses to falsely say they don't remember when they do, or to seize on one specific small element of a question to give a misleading portrayal in the answer.

I think the lawyerly response is to say "well sure, but that isn't perjury". And maybe it isn't, but there's room for more common sensical, colloquial notions of the word "lie". And under those definitions, you can very much say that lawyers coach their clients to lie.

Yeah. I feel similarly.

I think that it's a tricky area. There are both the lawyers who instruct their clients to ... let's say ... misinform during depositions.

And there are also even worse examples. I was at a deposition, and the deponent said "X did not happen." X happened to be an element of the claim. It was unequivocal. Before the deponent's attorney asked questions, he asked for a short five minute recess.

Afterwards, he asked a series of questions over the course of two minutes that led the deponent to say, "X happened." Deposition over.

(As a matter of truth, X did not happen. And any one with a brain, including a judge that looked at this later, came to the conclusion that the five minute break and subsequent questioning didn't pass the smell test ... but before there was any ruling, the case was dismissed by the deponent.)

There is a fine line, and ethical attorneys make sure to instruct deponents to tell the actual truth, not the "truth" attorneys want them to say. You can coach a witness to answer questions well, not to over-answer, and so on- but you don't coach a witness to lie, or to just barely escape perjury. At least, I don't.

Less alert lawyers notice after the deposition and submit affidavits from their clients contradicting their deposition testimony.

... don't get me started.

Heck, I will say this.

Also, is there anything more annoying that having a summary judgment that is a slam dunk, and seeing that SELF-SERVING affidavit filed, that was drafted by the attorney solely to create a dispute of fact, and that contradicts what was previously sworn to?

Okay, there are more annoying things. But that is right up there.

Eh. That doesn't bother me; it happens so often that I have a macro to paste the string cite telling the court why the sham affidavit must be disregarded.

Well, I guess l'm like Charlie Brown with the football.

I keep expecting a certain level of ethics and professionalism....

(There are a lot of good and ethical attorneys out there, but there are also a fair number of individuals who I wouldn't trust to watch my bag at a Starbucks.)

Even ethical lawyers have a problem with clients who mistakenly think you're telling them how to answer a question. No matter how many times you drill into them that your advice and instructions about how to answer questions do not override the primary instruction to tell the truth, you're going to have a client who says, after the fat, "But you told me to say that!" (Insert the Picard face palm meme here.)

With respect to "I don't recall," clients are usually "clever" (if that's the right word) to think of that on their own. I can't count the number of witnesses I'm prepping who've said, "Okay, I won't lie; I'll just say I don't remember. They can't prove that's false." Sometimes the best I can do is show them sample video of how bad it looks when deponents keep saying that.

Weissman clearly was trying to impugn the lawyer.

He didn't subscribe to your interpretation at the time of his tweet, as a straight reading of it reveals.

While that may be true, a fundamental weakness of the social network formerly known as Twitter is that it doesn’t allow enough space to permit people to provide context to qualify their opinions. There’s no space to, for example, state verified facts and then provide an opinion interpreting those facts.

So I think people who use it have to be aware that they may be subject to greater liability risk than in other media that allow space to provide nuance and context. The space only allows room for a short statement which the law is entitled to interpret as a statement of fact even if, on a different platform, people might post a longer statement that allows room for nuance, context, and qualification and permits people to see the oversll statement, after this additional content, as one of opinion.

What the author intended just doesn’t matter. What matters is how people in the audience can perceive it. It doesn’t matter if all the qualifiers were in the author’s head but didn’t get written down because there was no space to write them.

Use X, accept the risk.

"If you can truthfully say 'X', you get money. If you can't, you don't. Can you truthfully say 'X'?"

The decision seems to be correct as far as it goes. But I did want to flag one particular statement by the lawyer that seems to support the assertion that Cassidy was coached to lie:

"I don't want you to perjure yourself, but 'I don't recall' isn't perjury. They don't know what you can and can't recall."

What the questioner does or doesn't know doesn't determine whether the witness's statement is perjury. The witness either does or doesn't recall; whether the questioner doesn't know what the witness can or can't recall is irrelevant. There is no good reason for the lawyer to mention what the questioner doesn't know during advice to the to the witness except as a wink and nod about what she could get away with. Or at least a jury could so find.

Yes. My assessment too. And therefore, without going and reading the pleadings, I'm unclear on how did this not get tossed on ‘actual malice’ grounds. How can Passantino possibly allege that Weissmann knew/was reckless about his accusation's falsity?

(I assume Passantino must be at least a limited purpose public figure.)

Sounds like it's because of the context. Right after that, she said, "[H]e didn't tell me to lie. He told me not to lie."

Taken by itself, the statement you quote sounds like he's implying that she could lie about what she recalls. But if he's explicitly telling her not to lie, not so much.

Also, we don't know what he was referring to when he said "It's not perjury..." He didn't say that "I don't recall" is never perjury.

That's why I think it's a fact issue. There are at least two plausible readings of the remark.

I should say, though, that in 30-odd years of preparing witnesses, I've never made any mention of the unlikelihood of the questioner knowing whether the witness is telling the truth or not, and I am hard-pressed to think of a legitimate reason to mention that.

I am amazed that Stefan Passantino wants to see the truthfulness of Andrew Weissman’s implied assertion determined by a jury.

In 1982, CBS News broadcast that General William Westmoreland had deliberately understated Viet Cong troop strength during 1967 in order to maintain US troop morale and domestic support for the war. Westmoreland filed a lawsuit against CBS. He withdrew the suit mid-trial when it looked like the jury was likely to find the statement was true.

He may feel confident after escaping bar discipline. Or, in my opinion based only on widely published facts, getting away with behavior that warrants bar discipline.

Let's suppose that the case is tried with "lie" as a factual statement rather than an opinion based on all the accusations floating around.

The plaintiff will swear under oath that he never never never even hinted that a client should be at all dishonest. What admissible evidence says otherwise? Can the defendant get Cassidy Hutchinson to testify?

This case illustrates the difference between defense lawyers and everyone else. With defense lawyers, as with criminals, lying MEANS the government can convict you of lying. If the government can’tt convict you of lying, you didn’t lie. Ms. Hutchinson was clearly confused by this viewpoint.

Here the defense lawyer takes the view that the government can’t see inside your head, and what the government can’t see isn’t there and didn’t happen.

The criminal takes this same epistemological concept and merely applies varying degrees of affirmative action. The government can, of course, be actively prevented from seeing things. Activities can be concealed. Witnesses can be eliminated. Buf it’s essentially the same epistemology.

George Orwell’s 1984 dealt with additional means of epistemological affirmative action. It’s not enough that we merely see things. We have to notice them, and we have to remember seeing them. So in addition to manipulating the objects seen, there is the opportunity to minipulate the subject seeing. Memories and records in particular can be manipulated.

As with James Joyce, George Orwell was an atheist who had a worldview based on theological assumptions. Orwell wrote an essay on Ulysses in which he explained it as an attempt to address what happens when a person with a fundamentally theologically based worldview loses his faith. It reflected Joyce’s grappling with the anguish of losing his faith, a creative effort trying to fill the emptiness.

It was central to Orwell’s worldview that things exist and happened independently of our seeing and remembering them. To the theist this comes easily. Nothing is completely invisible. But atheism is premised on the proposition that if we can’t see things, they aren’t there. And this quickly becomes a very unworkable proposition in practice if a society wants to avoid degenerating into systematic criminality where those in power determine what everybody sees and remembers.. If we take the proposition to its logical conclusion, or even a few steps in its direction, ethics become easily circumventable.

A fundamental claim of people like Richard Dawkins is that beimg serious about science means we accept that if we don’t see things, they don’t exist. After all, Ms. Hutchinson’s perspective must look pretty naive and Mr. Passantino’s wise and worldly. But if that’s so, perhaps criminals and tyrants are the most serious scientists we have. And if that’s so, perhaps serious scientists are not the best people to run societies.

I think that was George Orwell’s real worry. Ultimately non-sollapsism depends on an assumption of an external reality that exists independently of us whether we can see it or not — the exact opposite of what is claimed to be “serious science. As Orwell noted, gasping with it as he gasped for breath, this is a very, very hard problem.

Oddball analysis, because it leaves out the primary verbs associated with the word ‘coach’, which are to teach or train, neither of which necessitates that the coach explicitly directed the pupil to commit or even understand that they were committing the concluding act. A classic coaching example would be “wax on, wax off”.

Having left out “teach” and “train”, the judges use of “instruct, direct, or prompt”, is a choice that is downright convenient to the decision.