The Volokh Conspiracy

Mostly law professors | Sometimes contrarian | Often libertarian | Always independent

Today in Supreme Court History

Today in Supreme Court History: July 31, 2018

Editor's Note: We invite comments and request that they be civil and on-topic. We do not moderate or assume any responsibility for comments, which are owned by the readers who post them. Comments do not represent the views of Reason.com or Reason Foundation. We reserve the right to delete any comment for any reason at any time. Comments may only be edited within 5 minutes of posting. Report abuses.

Please to post comments

Ex Parte Quirin, 317 U.S. 1 (decided July 31, 1942): allows Nazi saboteurs to argue their habeas petition before the Court, but upholds Presidential order that they be tried by a special military tribunal; admits that all federal courts are functioning normally but defers to Presidential authority in time of “grave public danger” and holds that the tribunal had power to try anyone regardless of citizenship or military status (eight Germans were deposited by submarines off Florida and Long Island with cash and explosives; it was known that the Hitler regime was training saboteurs but J. Edgar Hoover was inept at finding them, preferring to order dragnets on immigrant populations; the plot came to the FBI’s attention only because the leader, a former U.S. Army soldier, decided to turn them in before anything happened; he was one of the two who was not subsequently executed, but was deported to Germany in 1948 and tried for the rest of his life to get back into the United States)

“Regardless of military status?” Not so.

Quirin’s basis was that the petitioners were alleged to be attached to the German military as illegal combatants. Their militaty status was critical to the holding that it was lawful to try them by a military tribunal.

I'll revisit. Thank you.

It’s not stated that these men were in the German military. They arrived in German uniforms, perhaps to blend in with the crew on German naval vessels, but once onto our shores they switched to civilian clothes.

Also I don’t see anything in Stone’s (long) opinion that says only members of armed forces can be tried by military commission. His point is that they were engaged violation of the laws of war, and nowhere does he specify that such can only be committed by military. In a footnote he gives historical examples of civilians tried by military commission.

My understanding is that the uniforms were because the depositing by U-boat was the most likely time for them to be caught, and if they were wearing uniforms they would then need to be treated as POWs, not illegal combatants. Once they were clear they changed to civilian clothes to blend in with the civilian population.

Had they been caught in their uniforms none would have been executed, just held in POW camps and sent back to Germany after the war.

Personal note, my great grandfather was in the German army and was captured in the Mediterranean in 1943, he spent time in a series of POW camps in the US and was repatriated to Germany in 1947. He was never barred from visiting the US and even considered moving here in the early 80s.

Quite interesting, thanks. The men in Quirin were indeed arguing that they were POWs. As Stone put it in a footnote, “a soldier in uniform who commits the acts mentioned would be entitled to treatment as a prisoner of war; it is the absence of uniform that renders the offender liable to trial for violation of the laws of war.”

According to Ernie Pyle, who was writing from the Mediterranean in 1943, many of the German soldiers, scared kids, seemed glad to be captured.

Is a case like this addressed by the Geneva Conventions in any way?

I realize the Conventions came after WWII but was it addressed going forward?

The first Geneva convention was way back in 1864, with revisions/replacements in 1906, 1929, and finally 1949. The treatment of POWs and how legal combatants are defined were in place during WWII, it’s where the uniform/no uniform distinction came from (and it still exists under the current treaty today, hence the tribunals for al Quaeda prisoners during the Bush administration)

German soldiers certainly were more willing to be captured by the British or the Americans (who followed the Convention) than by the Soviets (who didn't).

That's for sure. I had a great uncle (brother in law of great grandfather) who was captured by the Russians. Obviously I didn't know him before the war but I'm told he was never the same afterward.

Quirin referenced and discussed the Hague Convention, which preceded the Geneva Convention.

Unlawful combatants are combatants, as distinct from civilian criminals.

It seems pretty difficult to argue with a straight face that people brought on a German military submarine and issued German military uniforms, and given orders designed to further the German war effort, weren’t “attached to” the German military. These were illegal combatants. But they were combatants all the same.

This clown retired at least 6 years too late.

“the leader, a former U.S. Army soldier”

Wikipedia informs me that a second one (Burger) was also a member of the national guard. Dasch died at age 88.

Quirin left something to be desired. Judgment, executions, full explanation later.

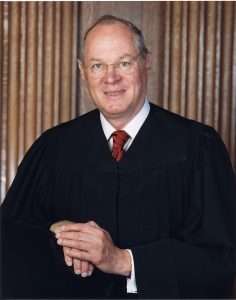

Kennedy’s retirement came after the Court term appeared to be over without any retirement. Then, he announced. He was on the Court for thirty years & was a court of appeals judge.

A few thought his retirement was sketchy but nothing out of the ordinary. It would have been the one no-problem SCOTUS confirmation process for Trump if the Kavanaugh mess didn’t arise.

admits that all federal courts are functioning normally but defers to Presidential authority in time of “grave public danger”

By 1942, FDR had made so many appointments to the Court that the Justices would have deferred to his authority even if he wanted to have the Quirin men summarily shot in front of them. The Supreme Court at that time was simply an extension of FDR.

Quirin is straightforwardly justifiable on constitutional grounds. The Constitution contains exceptions for military crimes. For example, the 5th Amendment contains such an exception. There was a long history of trying spies and saboteurs by military commission in the various wars the US fought in prior to WW2.

The defendants’ lawyer was Kenneth Royall, who had a bit of a profile-in-courage moment. Royall was assigned to defend the saboteurs before the military tribunal, but authorities didn’t want him challenging the tribunal itself. He wrote FDR for permission to challenge the tribunal in civilian court but (here’s a surprise) FDR wouldn’t commit himself one way or another. But Royall went ahead and fulfilled his professional responsibility by taking the case into civilian courts all up the way to the Supreme Court.

It didn’t stop Royall from political advancement. He was the last Secretary of War in U. S. history (before it was renamed Secretary of Defense), then Secretary of the Army.

Then he blotted his copybook by refusing to integrate the army as Truman ordered, thus ending up back in private life.