The Volokh Conspiracy

Mostly law professors | Sometimes contrarian | Often libertarian | Always independent

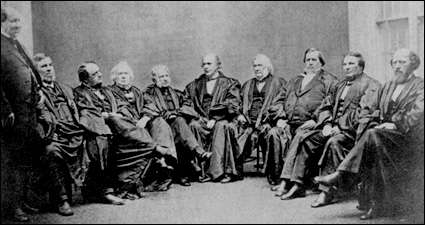

Today in Supreme Court History: July 17, 1862

7/17/1862: Congress enacts the Confiscation Act, which empowers the government to seize the property of the rebels. The Supreme Court considered the constitutionality of that law in The Confiscation Cases (1873).

Editor's Note: We invite comments and request that they be civil and on-topic. We do not moderate or assume any responsibility for comments, which are owned by the readers who post them. Comments do not represent the views of Reason.com or Reason Foundation. We reserve the right to delete any comment for any reason at any time. Comments may only be edited within 5 minutes of posting. Report abuses.

Please to post comments

Rubin v. United States, 524 U.S. 1301 (decided July 17, 1998): Rehnquist denies motion to stay subpoenas for testimony of Secret Service officers as to what they overheard Bill Clinton say in regard to the matters Kenneth Starr was investigating; Rehnquist concedes that “confidentiality” and “the physical safety of the President” are implicated, and assumes for the purpose of the motion that cert would be granted, but then denies the application on the grounds that the Circuit Court’s decision requiring compliance would be affirmed (?). Cert was denied, 525 U.S. 990, with strong dissents from Breyer and Ginsburg noting the history of Secret Service agents in close proximity to the President (and within earshot of his conversations) foiling assassination attempts (IOW, allowing these subpoenas will encourage future Presidents to absent themselves from Secret Service protection whenever sensitive matters are discussed).

Benten v. Kessler, 505 U.S. 1084 (decided July 17, 1992): rejecting pregnant woman’s request for return of the French abortion pill RU-486, which had been confiscated when she entered the country

Reproductive Services, Inc. v. Walker, 439 U.S. 1307 (decided July 17, 1978): In this abortion case involving medical malpractice and false advertising, where records as to five other patients had been subpoenaed, Brennan stays Texas court proceedings pending filing of a cert petition because the parties could not agree on keeping the patients’ names confidential. Brennan says that the issue presented -- whether patient names can be obtained without a protective order -- would merit granting cert, but cert was in fact denied on jurisdictional grounds, 439 U.S. 1133 (1979).

From the District Court decision in Benten v. Kessler:

https://casetext.com/case/benten-v-kessler

The FDA had authorized border inspectors to look the other way when people tried to import unapproved drugs for personal use, with certain named exceptions. The FDA later added RU-486 to the exceptions. Neither action was a formal rulemaking process. The plaintiff flew to London and came back the the forbidden pill, warning the government that she intended to break the law. The government obliged her by seizing her contraband. She convinced the court that the second agency action should not apply to her, the first should, and the discretion to allow importation of unapproved drugs should be treated as a mandate.

The lead plaintiff was really an agent of abortion rights activist Lawrence Lader who found a "a 29-year-old self-described anarchist and West Coast punk from the Bay Area" to create a test case. See The 'wild,' secret history of the abortion pill — found in a Massachusetts archive.

I think one of the "date rape" drugs was also added to the forbidden list in the 1990s. It was easily available in Europe and possibly Canada and Mexico. It was not approved in the United States. Customs used to look the other way. They were told to start confiscating the pill bottles.

Thanks!

I remember the Rubin case. President Clinton was asserting a "protective function" privilege to prevent Secret Service agents from testifying as to things they might have heard. As I recall, former President Bush came out in support of such a privilege, while former Presidents Ford and Carter, came out against it.

While I think such a privilege (limited to the President, as opposed to every Secret Service protectee, or even everyone with a bodyguard) is a good idea, just because something is a good idea doesn't make it a constitutional protection. Congress could certainly create such a privilege legislatively. Though I suspect the Court's recent presidential immunity decision renders the question academic, essentially making future investigations like Starr's nearly impossible, foreclosing prosecutorial inquiries into such matters even remotely tied to a President's "official acts".

As I recall, this act was one of the motivations for the 14th amendment. They understood that this act was, in fact, unconstitutional, and the 14th amendment was intended in part to rectify that before the judiciary got around to actually enforcing the Constitution again. (They'd rather taken a holiday from that duty during the war.)

I don’t see how that could be. The Supreme Court, in a series of cases, had already upheld the suspension of the writ of habeas corpus (in actual rebel-controlled territory), seizure of ships (the Prize Cases), and more, so by the time the Confiscation Cases were decided there was little doubt as to constitutionality. And since the 14th Amendment only applies to states, it didn’t impose any new obligations on the federal government in this respect.

I SAID the judiciary had taken a holiday from enforcing the Constitution during the war, didn't I? That's what a holiday from enforcing the Constitution looks like: The judiciary upholding unconstitutional laws!

They didn't expect that holiday to last, so they wrote themselves an amendment that constitutionalized what they'd been doing.

"And since the 14th Amendment only applies to states, it didn’t impose any new obligations on the federal government in this respect."

What it did, relevantly, was give the federal government new powers.

How is it that you think the fourteenth amendment retroactively empowered the federal government to pass this law?

Obviously, the enabling legislation clause, section 5.

Remember that the judiciary don't actually have the power to repeal laws. When they find a law unconstitutional, that just means that you can't get a court to treat it as a law, it doesn't disappear from the books.

So, if you enact a law in 1862, and several years later amend the Constitution so that it's constitutional, at that point the courts have no basis for refusing enforcement anymore. The fact that it wasn't constitutionally authorized at the time of enactment is irrelevant.

At most, people who'd been subject to enforcement prior to the amendment would have a case for relief. But not going forward.

This wasn't the first time that something was retroactively made constitutional, and it won't be the last.

Not sure why Noscitur is trying to split hairs here. Maybe it's a slow day at work?

"Split hairs"? Brett Bellmore made a very specific claim about this law which doesn't seem to make a whole lot of sense. I'm trying to give him the benefit of the doubt and see if there's something I'm missing rather than just assume that it's one of his anti-government just-so stories. So far, not looking good.

But what part of the fourteenth amendment do you think the Confiscation Act could have been seen as enforcing? And why is it that you think they forgot to talk about that in the Confiscation Cases?

"But what part of the fourteenth amendment do you think the Confiscation Act could have been seen as enforcing?"

Well, for starters, the act of '61's confiscation of slaves would have been an uncompensated taking, but for Section 4's "But neither the United States nor any State shall assume or pay any debt or obligation incurred in aid of insurrection or rebellion against the United States, or any claim for the loss or emancipation of any slave;"

The '62 act presumed to disqualify from public office any insurrectionists, but statutes cannot constitutionally add to the qualifications for federal office, and Section 3 of the 14th amendment cured that deficiency.

"And why is it that you think they forgot to talk about that in the Confiscation Cases?"

Hello, "holiday"?

The 14A arose from events after the Civil War, including concerns that the civil rights acts passed and/or proposed surpassed the powers of Congress.

“They” did not all think even that. Congress was divided on the question.

Different provisions also addressed specific concerns.

They also wanted to clearly put things in writing so if future congresses were not controlled by Republicans, certain basic things were clearly in place by constitutional amendment.

The idea that the Taney (Chase near the end) Supreme Court took a so-called "holiday' in cases like the Prize Cases was not what they were concerned about.

"They" was not meant to imply that the concern was universal, but perhaps I could have been more explicit about that.

And, "in part"; Of course the 14th amendment was doing other things, too.

And, yes, I think the Court did take a holiday; Not out of ideological sympathy with the war, but out of fear of what they might face if they didn't. They were already facing public calls to arrest them, particularly Taney, and Lincoln was not shy about jailing political adversaries.

I realize you think that.

And, yes, when tossing around “they,” it very well implies that it was a general opinion and significant concern.

There were also not some serious calls to arrest Supreme Court justices. Lincoln would know that that wouldn’t fly. The talk about Taney didn’t amount to much in the end.

The justices in the majority were also war unionists, including Southerners following the path of Andrew Jackson, who strongly opposed secessionist talk. The 14A also covers peacetime, when the rules are more strict.

Yes, general, just not unanimous.

Taney's autobiography indicated he expected to get arrested over Merryman, and in fact judge Merrick WAS arrested for refusing to comply with Lincoln's suspension.

So the threat was a lot more serious than you're making it out to be.

Sort of. Lincoln prepared to veto the Second Confiscation Act on various Constitutional grounds. Congress passed a joint resolution explaining and limiting the Act. Lincoln eventually signed the Act and sent his veto message to Congress, annoying a lot of people. Opponents of the law sought to publish the veto message, but were filibustered.

But basically if you want to consider Constitutional issues with the Act, Lincoln's veto message provides the ammunition. But how did the joint resolution change things, and did Lincoln's veto message serve as sort of a signing statement as to how he was going to enforce the law?

The reality was the Act was not enforced because it had no enforcement mechanism. The military continued to confiscate contraband under military law. Chase worked out a deal with the military to share the cotton seized. I think this background explains a lot of why Justice Chase believed an enforcement mechanism was necessary to implement Section 5.

And it’s still good law. The Suoreme Court for example upheld suspension of the writ of habeas corpus in an actual war zone during World War II. It merely held that once a couple of years had passed after Pearl Harbor and the fighting had moved further east, Hawaii was no longer a war zone.

Fighting moved east from Hawaii?

Easily 270 degrees East!

Yes — Japan is in the western Pacific.

That sound you're hearing is a roughly oblate spherical sphere flying past you along a great circle line.

I suspect that had Rubin been decided today, the court would have quashed the subpoena.

It’s remarkable how the judicial system never gave Clinton a break, while consistently giving Trump a pass.

Well, it's not like Trump has a law license, so they couldn't disbar him.

It's true that they enforced against Clinton a law he'd himself signed with great pomp. Bet he didn't see that coming.

Different Courts, different laws. We are certainly in a different era of executive permissiveness by the judiciary, however.

It is of zero legal import who signed the law and with what pomp.

No, business licenses and such would be more relevant. And, other penalties.

Clinton signs a law and in some fashion, he along with everyone else is bound by it?

No. I don't think he would find that problematic.

Poor Bill Clinton!

Married to Hillary AND no slack from the SC?

No wonder he got into one of a kind humidor collecting and fingerpainting intern dresses.

Sometimes a good hobby helps us forget how unfair the world can be.

Justice Strong wrote the Confiscation Cases. The opinion is a trudge to read. The opinion in part notes that the matter was addressed in an earlier case.

Benten v. Kesler had two public dissents.

"Justice Blackmun dissents and would grant the application to vacate the stay."

Stevens wrote an opinion. He argued there was an undue burden on her right to choose an abortion. The per curiam says that the only issues at hand are the Administrative Procedure Act and FDA regulations claims.

Note, this was decided after Planned Parenthood v. Casey & it can be realistically assumed [if not necessarily conclusively the case] that the plurality votes in that case did not dissent from this order.