The Volokh Conspiracy

Mostly law professors | Sometimes contrarian | Often libertarian | Always independent

Reflections on Juneteenth

Juneteenth celebrates a great American achievement, and a triumph for the nation's Founding principles. Also, the culture war over the holiday is lame, and hopefuly coming to an end.

Today is Juneteenth, the holiday commemorating the abolition of slavery in 1865—established as an official federal holiday in 2021. In 2021 and 2023, I wrote posts on the meaning of Juneteenth, and why culture war-driven attacks on it are lame, and should stop (they seem less common this year). Most of the points made then remain relevant, and I reprint them in this post with some modifications and additions:

Juneteenth commemorates the abolition of slavery in 1865. Some conservatives who opposed its establishment as a national holiday argued it might somehow detract from Independence Day on July 4, or promote left-wing identity politics. For their part, some on the left may view it as a condemnation of America's history of slavery and racism, or even a celebration of black nationalism.

In reality, however, the abolition of slavery was the greatest achievement of the universal principles underlying the American Revolution, and a rebuke to ethnic nationalism and separatism. Slavery was America's worst injustice, and its abolition is obviously worthy of celebration.

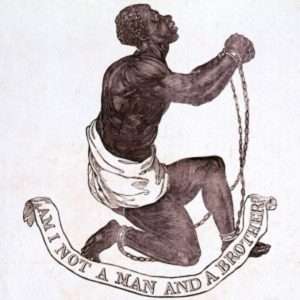

Abolition was only achieved thanks to a multiracial movement that emphasized the universality of the right to liberty, and the moral arbitrariness of distinctions based on race.

It is no accident that the antislavery movement was also accompanied by what historian Kate Masur calls "America's First Civil Rights Movement," which sought equal rights for blacks that went beyond simply abolishing slavery.

As Masur and other scholars have documented, both black and white abolitionists routinely cited the universalist principles of the Founding in making the case for abolition and racial equality, even as many of them also criticized the Founders (and later generations of white Americans) for their hypocritical failure to fully live up to their own principles. From early on, critics of the American Revolution denounced the contradiction between its professed ideals and the reality of widespread slavery. "How is it," Samuel Johnson famously wrote, "that we hear the loudest yelps for liberty among the drivers of negroes?"

While the hypocrisy and contradictions were very real, so too is the fact that Revolution and Founding made abolition possible, in part by giving a boost to universalistic Enlightenment liberalism on both sides of the Atlantic. Among other things, the Revolution inspired the First Emancipation in the US (the abolition of slavery in the North that became the first large-scale emancipation of slaves in modern history). Without the First Emancipation, we could not have achieved the second and greater one.

For all their failings, the Revolution and Founding paved the way for abolition. That happened in large part because they were the first large-scale effort to establish a polity based on universal liberal principles rather than ties of race, ethnicity, or culture.

Those principles are at the root of most of America's achievements, of which the abolition of slavery was among the most important. They are also what enabled America, at its best, to offer freedom and opportunity to people from a wide range of racial and ethnic backgrounds from all over the world.

While right-wing critics fear that Juneteenth is somehow anti-American, some more left-wing commentators emphasize that slavery was not fully abolished on June 19, 1865, which was merely the date when Union troops reached Galveston, Texas, and announced the implementation of the Emancipation Proclamation in one of the last parts of the former Confederacy where it had not yet been implemented. Slavery was not legally banned throughout the United States until the ratification of the Thirteenth Amendment in December 1865, and some slaveowners continued to resist emancipation even after that point.

But the Juneteenth holiday is nonetheless meant to commemorate the end of slavery as a whole, and that is in fact how it has been understood for many decades, long before it became a federal holiday. June 19 is the traditional date for commemoration of abolition, even if it is not the anniversary of the day on which the last vestiges of slavery were actually banned. Similarly, we celebrate Independence Day on July 4, even though July 2, 1776 was the date when the Continental Congress actually voted for independence, and independence was not fully achieved until the Treaty of Paris ended the Revolutionary War in 1783. Until that latter date, large parts of the US remained under British control.

Ultimately, the holiday commemorates a great achievement, even if that achievement was not fully completed on any one day, and in some ways remains incomplete even now. The struggle for freedom is ongoing, and never fully won. But there can still be great milestones along the way, of which the abolition of slavery was likely the most important.

Abraham Lincoln, the president who issued the Emancipation Proclamation whose belated enforcement Juneteenth celebrates, put it best in his famous speech on the Declaration of Independence and its implications for slavery:

I think the authors of that notable instrument intended to include all men, but they did not mean to declare all men equal in all respects…. They did not mean to assert the obvious untruth, that all were then actually enjoying that equality, or yet, that they were about to confer it immediately upon them…

They meant simply to declare the right, so that the enforcement of it might follow as fast as circumstances should permit.

They meant to set up a standard maxim for free society which should be familiar to all: constantly looked to, constantly labored for, and even, though never perfectly attained, constantly approximated, and thereby constantly spreading and deepening its influence and augmenting the happiness and value of life to all people, of all colors, every where.

The success of the antislavery movement's appeal to liberal universalism has been a model for later expansions of freedom, as well - including equal rights for women, the Civil Rights Movement of the twentieth century, and the struggle for same-sex marriage. It is a model that advocates of migration rights would do well to emulate today.

The work of fully living up to the ideals of the Founding wasn't completed in Lincoln's time, and it remains seriously incomplete even now. But Juneteenth commemorates perhaps our greatest step in the right direction. And it reminds us that further progress towards liberty and equal rights depends on applying the same principles that made abolition possible.

Show Comments (282)