The Volokh Conspiracy

Mostly law professors | Sometimes contrarian | Often libertarian | Always independent

Conflicting Evidence on Public Support for YIMBY Zoning Reform

Recent studies diverge on the extent to which public opinion backs policies that would deregulate housing construction. YIMBYs would do well to learn from both.

Curbing exclusionary zoning and other regulatory barriers to housing construction is essential to reduce housing costs, enable more people to vote with their feet and "move to opportunity," make the economy more productive, and protect property rights. A bipartisan, cross-ideological "YIMBY" ("yes in my backyard") movement has arisen to promote housing deregulation.

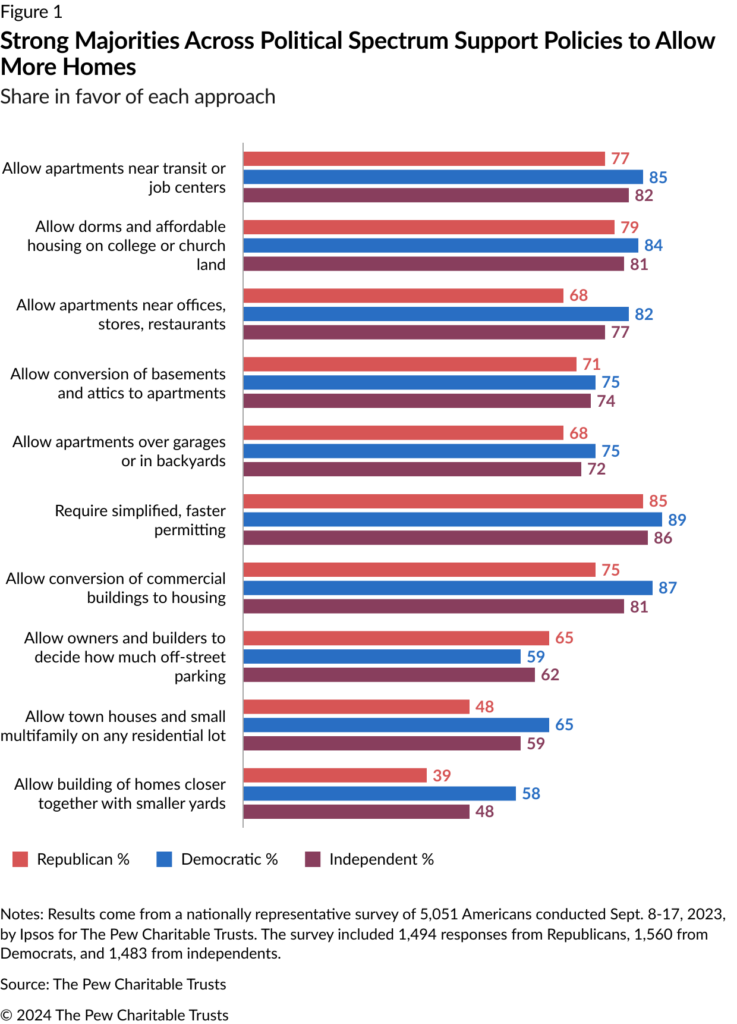

YIMBY policies command broad support among economists and land-use experts across the political spectrum. But how popular are these ideas with the general public? Two recent studies give diverging answers to that question. A September 2023 survey conducted by Pew Charitable Trusts finds broad support for a wide range of YIMBY policies, cutting across partisan lines. By contrast, a recent study by legal scholar Chris Elmendorf and political scientists Clayton Nall and Stan Oklobdzija (ENO) is far more equivocal, finding much less support for housing deregulation.

Which is right? I suspect the truth lies somewhere in between. It may well be that many voters don't know much about these issues, don't have strong opinions about them, and therefore their views (and answers to survey questions) may vary a lot based on context and framing.

The Pew survey finds large majorities supporting many different deregulatory housing policies.

Notice that every one of these policies has the support of a large majority, with the exception of allowing homes to be built closer together, with smaller yards, where respondents are evenly divided (49% for, 50% against). Most significantly, a clear majority (58%) supports allowing construction of multifamily homes on any residential lot. This would eliminate single-family-only zoning, the most widespread and pernicious type of exclusionary zoning. It is also notable that Democrats and independents tends to back YIMBY reforms more than Republicans do, despite the latter's reputation as being more sympathetic to property rights.

The Pew study also finds large majorities backing a wide range of rationales for housing policy change, including "To enable people to live closer to offices, stores, restaurants or public transportation" (77% say this is either an "excellent" or "good" rationale for policy change), and "To make housing more affordable" (82%), and "To help boost local economies by helping business owners have more potential employees and customers nearby" (76%). Most impressively, 65% say it would be excellent or good to adopt housing policies that "give people more freedom to do what they want with their property." Almost all building restrictions infringe on homeowners' property rights in that way!

By contrast, the ENO study is far more pessimistic about public support for YIMBYism. Here is the abstract summarizing their findings:

How much has rising political attention to problems of housing affordability translated into support for market-rate housing development? A tacit assumption of YIMBY (``Yes In My Backyard'') activists is that more public attention to housing affordability will engender more support for their policy agenda of removing regulatory barriers to dense market-rate housing. Yet recent research finds that the mass public has little conviction that more housing supply would improve affordability, which in turn raises questions about the depth of public support for supply-side policies relative to price controls, demand subsidies, or restrictions on ``Wall Street'' investors, to name a few. In a national survey of 5,000 urban and suburban voters, we elicited perceptions of the efficacy of a wide range of potential state policies for ``helping people get housing they can afford.'' We also asked respondents whether they support various housing and non-housing policies. Finally, as a way of estimating the revealed importance of housing-policy preferences relative to the more conventional grist of state politics, we elicited preferences over randomized, three-policy platforms. In a set of results that recall the politics of the inflation-ridden 1970s, we find that homeowners and renters alike support price controls, demand subsidies, restrictions on Wall Street buyers, and subsidized affordable housing. The revealed-preference results further suggest, contrary to our expectations, that price controls and anti ``Wall Street'' restrictions are very important to voters. Contrary to the recommendations of housing economists and other experts, allowing more market-rate housing is regarded as ineffective and draws only middling levels of public support. Opponents of market-rate housing development also care more about the issue than do supporters. Finally, we show that people who claim that housing is very important to them don't have distinctive housing-policy preferences.

The major differences between the Pew survey and the ENO study are that the latter asks more complicated and detailed questions, and that they intersperse questions about YIMBY policies with questions about pro-regulatory policies (e.g. - rent control and restrictions on developers), which most experts consider to be ineffective (rent control has a particularly bad reputation among those in the know), but which are clearly popular with many voters. ENO also leave more room for uncertainty and ambiguity (including allowing "don't know" answers), whereas the Pew questions have a "forced choice" format, with no "don't know" or "uncertain" option. The latter approach probably elicits more weakly held views than the former.

I also think the Pew question wording is relatively more favorable to YIMBY policies (sometimes implicitly suggesting they are likely to increase supply), while ENO's question wording often cuts the other way. ENO also include questions that reference corporate and developer interests, which may trigger "anti-market bias" and "supply skepticism." An earlier ENO study found that many people don't understand basic economics of housing and don't believe increasing supply is likely to reduce prices, suspecting instead that it will just benefit nefarious financiers and developers.

Interestingly, while the Pew study finds that Democrats are more supportive of deregulatory YIMBY policy than Republicans, ENO find the exact opposite. I think that, too, is an effect of question wording. The ENO questions more often often refer to developers and corporations, thereby triggering left-wing suspicion of capitalist interests.

Activists and politicians love to tout poll results that indicate their positions are popular, while denigrating those that suggest the opposite. I'm a big supporter of YIMBYism, and therefore wish I could say the Pew survey is right and ENO are wrong. But the truth is far more complicated than that. If anything, the ENO study is the more extensive and sophisticated of the two. As a longtime scholar of voter ignorance, I am well aware that many bad policies are popular, and that I myself have many unpopular views.

What the combination of the two studies shows is that public perceptions of housing policy are heavily influenced by frames and question-wording. If you ask about YIMBY policies in isolation, and imply they may increase the availability of housing and reduce costs, you will get strong majority support for them. If you have less favorable question wording, reference capitalist interests, and include questions about increased regulation, you get more negative results.

Similarly, if you frame deregulation as "giv[ing] people more freedom to do what they want with their property," it will get more support than if you frame it as letting developers and other business interests do what they want - even though these two are often the exact same thing! Business interests are owners, too, after all, and one of the things that an ordinary property owner might want the "freedom" to do with her land is sell it to a developer to build new housing that can accommodate more people.

Both the seller and the developer may be motivated by profit, rather than any high-minded desire to increase affordable housing. But, to paraphrase Adam Smith's famous statement about butchers, brewers and bakers: "It is not from the benevolence of the builder and the developer, that we expect our housing, but from their regard to their own interest."

While ENO use a more sophisticated methodology, it's not clear their approach better captures voters' responses to real-world political campaigns. In the real world, voters rarely carefully compare a wide range of policy options with nuanced wording. They often just see or hear about just one or two ideas at a time. Thus, I still think libertarians and YIMBYs would be well-advised to use referenda to promote their policies, in states where it is relatively easy to get questions on the ballot. A referendum question focuses on one policy at a time, and can be worded in a way that creates a favorable frame. Effective framing might also facilitate passage of traditional legislative proposals.

That said, ENO are right to warn that increased public focus on housing issues won't necessarily lead to better policy. Even if more YIMBY reforms get adopted, they may be vitiated by populist policies that actually make housing harder to build:

Our results imply that the more the public tunes in, the more likely it is that the hoped-for balance will be upset by populist candidates demanding stricter rent controls, tighter limits on corporate ownership of housing, and ever more demanding standards for deed-restricted affordability in new projects. Some relaxation of zoning restrictions may be achieved, but its effect is likely to be vitiated by a host of other requirements that make new housing economically infeasible to build.

This warning is well taken. But it doesn't mean YIMBYs should eschew political action entirely, or even that they should always avoid calling greater attention to housing issues. Far from it. still, the threat of ignorance-driven populism should engender some caution. It also reinforces the case for combining political action with strategic litigation, using the Takings Clause of the Fifth Amendment and various state constitutional provisions. Such a combination of strategies has served many previous reform movements well, and could work for this one, too.

Editor's Note: We invite comments and request that they be civil and on-topic. We do not moderate or assume any responsibility for comments, which are owned by the readers who post them. Comments do not represent the views of Reason.com or Reason Foundation. We reserve the right to delete any comment for any reason at any time. Comments may only be edited within 5 minutes of posting. Report abuses.

Please to post comments

Question should be: Do you favor doubling the density of your residential neighborhood in order to help make room for Libertarian proposals to import millions of Third World migrants?

So many take all Somin posts as an excuse to tiredly post tepid old and busted nativist talking points.

There is something anti-American in most of what he posts.

Yeah, he supports anything that would make life worse for US citizens. Maybe he's working for a foreign government.

“Reducing housing costs” is another way of saying “reducing housing values.” Some 65% of Americans own their homes. For most of them, their home is by far their most valuable asset. Many have spent decades slowly building up equity in those homes. Under Somin’s proposed course of action, these homeowners would be robbed of trillions of dollars in equity.

Of course, they will never willingly agree to this, so the great libertarian calls upon the iron fist of government to force them. Somin does not see the United States as a place with a people bonded by a common culture, history, and values; in fact, as he has frequently noted, he despises such a notion. Rather, he sees the United States as some sort of international economic opportunity zone and shopping mall.

How do you figure?

What am I missing? I thought Somin’s point was to push down housing prices. Get rid of zoning and make houses cost less, right? Part of it would be increased supply (maybe, if demand does not continue to exceed supply), and another part would be the hit to value accomplished by degrading neighborhoods with unwanted density (for certain).

By the way, you know how right-wingers trumpet the housing-price advantages of moving to places like Houston? It is worth reflecting how much of that is attributable to the virtuous right-wing political character of Texas, and how much attributable to the fact that a no-zoning housing policy degrades value.

Zoning is alive and well in Texas. The only major area without zoning is the City of Houston. And, even there, there is de facto zoning in most neighborhoods through deed restrictions. So the lack of zoning has not led to any sort of housing renaissance.

Housing is cheaper in Texas largely because there is so much available land, good highways, no unions, a relatively easy permitting process, and fewer regulations that would allow activists to sue and run up the cost of projects.

I do agree that zoning (whether by government design or private action) is an affirmative good. The only major area in Houston that lacks effective deed restrictions (i.e., private zoning) is the Heights where auto repair shops and single-family homes exist side by side. The Heights stands as an example to all HOAs to vigilantly enforce the deed restrictions before they are deemed to have been waived. So, HOAs don't make that mistake any more.

In any event, few, if any, neighborhoods are built in Texas without deed restrictions and HOAs even where zoning exists. Why? Because developers know that deed restrictions add value.

I should also note that the lack of zoning in Houston leads to really stupid stuff like building homes in the runoff areas below flood control dams.

No. The idea isn't that a house on an acre at 123 Main Street would become cheaper. It's that you could, say, subdivide that into four quarter acre lots, or even build a multi-unit building on that acre. Each new house would be cheaper than the original one. But precisely because of the new potential value being unlocked, the original lot would increase in value. So it's good for the homeowners if they want to sell, and no skin off their back if they want to stay.

It's only good for the one homeowner who builds multi units on his lot, all the neighbors lose the value of their properties once there is a multi-family next door with section 8 tenants' kids burglarizing the neighborhood.

They did not "spend decades" doing any "building." These aren't generally people who acquired fixer-uppers and then did the work to improve the home. Rather, they just passively lived somewhere, and outside forces sometimes caused their homes to increase in resale value.

A home is not primarily an investment vehicle; it's a place to live. These people would continue to be able to live in their homes — and if the values decreased, so would their property taxes. It's true that if that happened, then if/when they choose to move, they would realize less money. But, then, they would be able to acquire a necessary new place to live more cheaply as well. The only people who really suffer are their heirs, but artificially propping up prices to benefit people who did nothing to earn those values is perverse.

"They did not “spend decades” doing any “building.” These aren’t generally people who acquired fixer-uppers and then did the work to improve the home. Rather, they just passively lived somewhere, and outside forces sometimes caused their homes to increase in resale value."

This is uncomfortably close to Marx's view of capital owners as "parasites." It is also ignores the absolute (not percentage) change in value. If I own a $1 million house today and downsize to a $500,000 one, I am left with $500,000 cash. If we cut the value of my house and the replacement house by 50%, I am left with only $250,000. A primary residence may not be a pure investment, but it is most definitely an asset. And massively cutting the value of those assets would have a tremendous negative effect on the economy that needs to be taken into account alongside any projected benefits from expanded, cheaper housing options.

"....if the values decreased, so would their property taxes. It’s true that if that happened, then if/when they choose to move, they would realize less money."

The first sentence is objectively false, at least to the extent that the claim is that the amount of decrease will be proportionally the same. Population growth entails infrastructure and other costs that are expensive to procure and maintain. More schools and teachers (with their bloated overhead), more parking, more roads, more police (with their bloated overhead), more sanitation (with their bloated overhead), more gas lines, more sewer lines, etc.

To oversimplify slightly, if population doubles and housing prices are cut in half, infrastructure costs will double, and thus property taxes will need to stay the same absent new, outside sources of funding. Of course there may be some synergies and economies of scale, but the population increase will most certainly not be a wash to existing homeowners.

"They did not "spend decades" doing any "building." These aren't generally people who acquired fixer-uppers and then did the work to improve the home. Rather, they just passively lived somewhere, and outside forces sometimes caused their homes to increase in resale value."

They built equity by paying off a mortgage instead of paying rent and inflation added to their value.

"A home is not primarily an investment vehicle"

All my homes over 50 years have been my best investment vehicles. The best one I bought for $28k and sold for $195k.

They did not “spend decades” doing any “building.” These aren’t generally people who acquired fixer-uppers and then did the work to improve the home. Rather, they just passively lived somewhere, and outside forces sometimes caused their homes to increase in resale value.

Nieporent, not in the DC area. Not in Eastern Massachusetts. When real estate appreciates in value, that delivers economic means to the owners. It enables the formerly penurious to improve their improvements, and thus leverage the value increase. To take advantage of that opportunity is commonplace to the point of near-universality.

I grew up in a tract subdivision in the 1950s, built by a developer who subdivided a disused golf course, offered a choice of 3 model homes to would-be buyers, and covered the ex-golf course with repetitions of those designs, all shoddily constructed.

That was just what my parents needed; we were not rich enough for the better suburbs. The newly-built house they bought at the then-outer-limits of the DC suburbs cost a whopping 4-figure price.

Twenty years later, my parents were delighted to discover they could sell that same house for more than $100,000. Like almost everyone else in that subdivision, they had done little to improve the house except to correct on an as-needed basis the developer's shoddy construction practices. The entire subdivision still looked almost exactly as it had, except with taller trees and bushier bushes.

Today, if there is any home in that subdivision which has not been renovated and rebuilt beyond recognition, I cannot find it. The whole former golf course looks like an assemblage of architect-designed originals. I doubt there is any home in it that can be had under a million dollars, with many going for twice that. The architects who did the redesigns could have done better. But no one seems to care that the place looks like a fever-dream outcome from a bad-taste contest. Everyone got rich except my parents, who sold way too soon.

That same process has only recently begun in the eastern Massachusetts neighborhood where I fled at the outset of the pandemic, to downsize and begin retirement. The house I bought had, like its neighbors, already multiplied several-fold in price, compared to typically 1960s baselines.

That touched off the mass renovation process locally. In the nearly 4 years since I purchased it, my home has nearly doubled in value, propelled upward by neighboring improvements. And of course I am using some of that increased value to fund improvements of my own.

If the process continues around me, as I expect, local home owners all around me will enjoy near-millionaire status less than 5 years hence. Most live in subdivisions which have yet to see their first paved road. But they are renovating furiously, to leverage their windfalls.

Whether that process is good or bad for housing policy I will leave to others to decide. But it is by no means the lackadaisical passivity you describe. None of my neighbors started out rich or exclusive-minded—folks like that would not have stepped foot in these swamp-Yankee environs.

Seems like YIMBY really should be YISEBY (Yes, in someone else’s backyard).

Especially in the cases where a governor is involved because they want to do the exact OPPOSITE of YIMBY and instead push YIMS (Yes in my state) policies.

Montana TOOK AWAY the right of local communities, i.e., THE PEOPLE WHO OWN THE "BACK YARDS," to determine local housing/zoning policies.

How exactly is that YIMBY?!?

Prof. Somin makes some decent points about housing and zoning - BUT YOU ABSOLUTELY CANNOT CALL IT YIMBY when the local community is cut out.

"Communities" don't have rights; only people do.

But the people who live in local communities certainly have rights.

It is normative vs positive. Sure, a state legislature can, generally speaking, arrogate to itself the authority to set zoning standards and classifications statewide. But that doesn't meant they should.

As a matter of policy, I and I suspect most others, favor zoning decisions to be made at as local a level as possible.

Democrats tend to live in denser neighborhoods. Some of these questions are asking them whether they would allow something that already exists.

I want to see the results sorted by urban/suburban/rural.

I want to see results of a poll that asks about these sorts of policies applied to the respondents' own neighborhoods.

A good side effect of more housing and more housing at lower prices is broadening the tax base as the problem many are facing is property taxes combined with school taxes are pricing some out of their homes