Why are housing prices in America so unbelievably high, especially in the country's most desirable locations? The superficial answer is "supply and demand," but the deep answer―the reason supply is so low―is a regulatory system that treats developers like criminals.

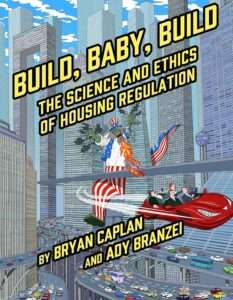

In Build, Baby, Build: The Science and Ethics of Housing Regulation, economist Bryan Caplan makes the economic and philosophical case for radical deregulation of this massive market―freeing property owners to build as tall and dense as they wish. Not only would the average price of housing be cut in half, but the building boom unleashed by deregulation would simultaneously reduce inequality, increase social mobility, promote economic growth, reduce homelessness, increase birth rates, help the environment, cut crime, and more.

Combining stunning homage to classic animation with careful interdisciplinary research, Build, Baby, Build takes readers on a grand tour of a bona fide "panacea policy." We can start realizing these missed opportunities as soon as we abandon the widespread misconception that housing regulation solves more problems than it causes.

And here are some early endorsements:

"Bryan Caplan and Ady Branzei have written a fantastically accessible and fantastically fun book explaining why housing is so expensive in the U.S. It is full of insight and sound economic reasoning. I can think of no better book to read for an introduction to understanding why land-use regulations have caused so much damage. It is a perfect book for your 17-year-old daughter or your 70-year-old uncle, for intro econ students or Nobel laureates, and for everyone in between." -- Ed Glaeser, Fred and Eleanor Glimp Professor of Economics and chairman of the Department of Economics, Harvard University

"Bryan Caplan is a pioneer in the use of graphic novels to expound economic concepts. His new book Build, Baby, Build is thus a landmark in economic education, how to present economic ideas, and the integration of economic analysis and graphic visuals. If you want to learn the economics, ethics, and political economy of YIMBY― namely the freedom to build this is the very best place to start." -- Tyler Cowen, Holbert L. Harris Chair of Economics at George Mason University and founder of Marginal Revolution

"The issue of building more is too important to be left for dry monographs. Fortunately, Bryan Caplan is on the case with another in his string of original, brilliant, and important books that is also readable and engaging. After my son read Open Borders, he asked me for recommendations of other graphic novels that were just as educational, insightful, and engaging. I finally have a second book to recommend to him." -- Jason Furman, former chair of the Council of Economic Advisers and Aetna Professor of the Practice of Economic Policy, Harvard University

"Fabulous! Housing deregulation is an issue in which the libertarians have been changing the minds of the liberals (whether or not they admit it), as we see in liberal YIMBYism. This is the book where you can find the arguments advanced, both rigorously and entertainingly." -- Steven Pinker, author of Enlightenment Now: The Case for Reason, Science, Humanism, and Progress

I will add that I have read the book myself, and I think it's a great achievement, even though I'm not normally a fan of the graphic novel format. In that respect, it's a worthy successor to the author's previous book in the same format, Open Borders (which I discussed here).

I was about to make another comment about your all-white, all-male universe but then I saw you have a white woman as eye candy in the back seat.

Two critical points of destructive contact between the ecological well-being of humanity, and its day-to-day customary activities, are the real estate development industry, and GMO agriculture. Simply to leave each of those activities to its accustomed level of regulation is to invite ecological disasters. Both require far more regulation, world-wide, not less.

There is little sign that will happen promptly, of course. Only a tiny percentage of humanity have any inkling what ecological issues even are, let alone insight into why getting them wrong creates public peril.

As an educational challenge, it is far from trivial to introduce nature-related issues to life-long urban-area denizens whose daily routines since birth have relied on other people paid to manage against natural impingements, and suppress general awareness of them. Thus, vital industries such as the property insurance industry, the energy generation and distribution industry, and even industrial agriculture itself, depend critically on a lack of public awareness. They rely on current practices which will foreseeably prove unsustainable; it is not their interest to let naturally imposed future risks get publicized.

Already, there are very large urban areas—in this nation, and abroad—which would be promptly depopulated if ongoing information suppression efforts were interrupted. People can be expected to flee foreseeable economic risk even before it is actually realized. The most alert people will figure it out, and depart first. Others will hang back and hope for the best.

Thus, educational effort necessary to inculcate necessary ecological information will probably begin relatively late, during a process of natural de-stabilization so advanced that it impinges inconveniently and unavoidably on almost everyone. Even when that happens, a business population whose paychecks depend on not understanding necessary truths will pose an impediment. They increasingly will organize politically to defend their paychecks instead of their lives—which will likely become imperiled by that inattention, along with the wellbeing and lives of everyone else.

Enduring economic interests, including not only those of business corporations, but also those spread piecemeal among the population, will be seen as threatened. Eventually, a great many people who don't know, and don't want to know, will nevertheless prove alert to understand that broader knowledge would instantly imperil the stability of an economic regime reliant on imposed and guarded ignorance. Those, too, at least on a momentary basis, will have an interest to continue to suppress broader insight, but they won't stick with it.

For a glimpse of a future which operates that way today, take a look at the real-estate reinsurance industry. To allay disruptive insight into economic perils now manifest in especially dangerous regions, the reinsurance industry has stressed to the breaking point the tolerance of people with real estate investments in safer areas—who recently began to endure gigantic and otherwise inexplicable cost increases. Those increases have been imposed to pay off losses—both losses already suffered, and losses anticipated to be suffered—by the more-endangered elsewhere. The aim has been to get the most ill-advised risk takers paid off, without sending them price signals so unmistakable that they and others would begin to flee, and thus undermine local political systems.

The book recommended in the OP is part of that effort to organize against insight now. That will leave the question of future insight to the chance of jostles and jolts from natural systems. Those will raise the stakes later.

We have a housing shortage because the USA has been flooded by legal and illegal migrants. Caplan and Somin are big advocates of open borders. Thanks, guys!

Wow. Tyler Cowan thinks this is a great book.

BFD.

Ilya, let me tell you something. I have read the George Mason econ gang's blog off and on for years. Some of them, not all, are indeed bright guys.

But the collective egomania is boggling. If Caplan looks out the window and says, "It's raining," the rest of them howl about what a magnificent insight that is. Hansen is the worst, or rather the treatment he gets is. He doesn't even need to do more than just nod to be hailed as one of the great geniuses of all time.

And it's not just collective. The individual levels of self-regard are also stunning. They know everything. Remember when Caplan disproved the existence of mental illness?

So I'm unimpressed by his endorsement.

As for the others, well, Glaeser has been on this horse for a long time, so predictable, and Pinker seems unaware that many liberals have been supportive of these ideas for a long time - before Caplan was heard of.