The Volokh Conspiracy

Mostly law professors | Sometimes contrarian | Often libertarian | Always independent

How Has Legal Academia Changed Since Posner on Meltzer?

Revisiting Posner's 2007 essay.

Back in 2007, Richard Posner published a very interesting reflection on the state of the legal academy in the form of a memorial essay to his colleague Bernard Meltzer. It's a very brief essay, only 3 pages long. But Posner's essay laments the loss of the former generation of lawyer-scholars that used to populate law schools. In the old days, Posner says, there were lots of law professors who were superb lawyers steeped in lawyering. These days, Posner says, that model is largely gone. Today's professors see themselves as academics first and lawyers second. Posner suggests that the best education and the best scholarship is a mix of the two. Both the lawyer-model and the academic-model are useful in their own ways. A student should get a healthy mix of the two, and scholarship of both kinds is very useful.

Over at X, in response to a tweet from me on the essay, Adam Unikowsky asked a good question:

Do you think the relationship between lawyering and legal academia has changed since Posner wrote that 16 years ago? If so, in what direction?

I don't have any special expertise on this question, but I have two tentative thoughts on it.

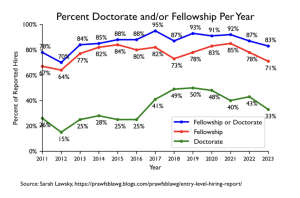

First, in some ways, the trend towards the academic model has only accelerated. Sarah Lawsky keeps numbers on the entry-level classes, and her annual report includes a chart on the percentage of new hires with doctorate degrees:

The green line is the key here. Note the jump from around 25% from 2011 to 2016 to the 40-50% range starting around 2017. And as Lynn LoPucki noted in his 2016 essay, Dawn of the Discipline-Based Faculty, the trend is even more pronounced at the "elite" schools. At my own institution, UC Berkeley Law, having a Ph.D. is effectively now the norm for entry-level hires. It's certainly not required. But a majority of entry-level hires have one.

Doctorates, or their absence, isn't a perfect proxy for the dynamic Posner describes. But it's in the ballpark. And the trend toward even more Ph.Ds suggests that, on the whole, the trend Posner noted has accelerated.

That's one part of the picture. But there's another set of developments that cuts the opposite way.

In the last fifteen years, many law schools have made significant improvements in expanding programs that are beyond the scholarship-line tenure-track professors, as well as breaking down barriers that used to divide the different parts of the faculty. Many schools have expanded clinics, hiring new faculty to teach clinics who are outstanding practitioners as well as academics. They have expanded legal writing programs, bringing in excellent lawyers as professors of legal writing. Some schools have added "professors from practice", leading senior practitioners who join the faculty to teach classes and participate in the life of the law school but are not on the tenure track.

This is a big generalization, and I hope I'm not too far off in this description. Describing a diverse area like legal academia reminds me of the parable of the blind men and the elephant. You never know if what you experience is just one part of the elephant. (If you think I'm off, please let me know in the comment threads.) But my sense is that these changes have had a significant impact on the kinds of faculty that a law student might encounter. When I was in law school, three decades ago, it was common to go through three years pretty much only encountering the regular podium scholarship faculty. But my sense is that's rare today, if not entirely unheard of. Today's law students are going to be taught by legal writing professors, clinical professors, professors from practice, and of course adjunct professors. All of them are likely to be excellent lawyers steeped in lawyering.

In short, I think there have been two changes since Posner's critique that cut in somewhat opposite directions. On one hand, the trend Posner saw has accelerated, with more Ph.Ds. than before. On the other hand, schools have made very helpful and important strides towards recognizing the critical role of faculty beyond the podium tenure track.

Editor's Note: We invite comments and request that they be civil and on-topic. We do not moderate or assume any responsibility for comments, which are owned by the readers who post them. Comments do not represent the views of Reason.com or Reason Foundation. We reserve the right to delete any comment for any reason at any time. Comments may only be edited within 5 minutes of posting. Report abuses.

Please to post comments

Sounds like you're describing Blackman. Except that he is neither an academic nor a practicing lawyer...rather a shameless fame whore

All of these guys are—they are lazy and didn’t want to use their big brains to design rocket ships to Mars. They are wasting a national resource (brain power) on this nonsense.

Having read several of his books, I've always been a fan of Posner, a great scholar and a great judge. My son has always been very proud of getting a A in Posner's legal writing class.

Are there any identifiable trends for which schools are hiring the doctorates? Are they concentrated at T-14s or T-50s? Or are lower ranked schools and schools that are generally more regionally focused in their student bodies and training also seeing increases in this type of candidate?

Are there any trends in the subjects the schools are hiring those with doctorates for?

Are there any identifiable trends for which schools are hiring the doctorates? Are they concentrated at T-14s or T-50s?

"And as Lynn LoPucki noted in his 2016 essay, Dawn of the Discipline-Based Faculty, the trend is even more pronounced at the "elite" schools. At my own institution, UC Berkeley Law, having a Ph.D. is effectively now the norm for entry-level hires."

Doh scrolled too fast. That is about what I expected.

I wonder if this is driven by "scholar envy." My only basis for this is law professors I know, who tell me no one wants to teach the nuts and bolts of legal practice.

Instead, they consider themselves deep scholars, with research interests that transcend mundane matters like torts and contracts, and whatnot.

That's OK, I guess, but then do away with the silliness of law reviews, and subject their scholarship to the kind of rigor that other academic disciplines require.

I wonder if it's driven by the larger institution's (eg UCLA) accreditation because that gets hurt by % of faculty who don't have a terminal degree, i.e. PhD.

The bigger question is what do they have PhDs *in*. That's the question you want to ask...

For example, someone teaching education law likely will have an EdD, and someone teaching environmental law may have a Biosciences PhD -- there's so much that isn't law that you have to know.

OTOH, are people going the LLM/Law Doctorate route? 0r do they have doctorates in social justice or womens studies?

.

No. This has been yet another episode of Simple Answers to Stupid Questions.

May I ask the basis of your conclusion?

If there is incredible pressure to have accounting and nursing taught by people with doctorates, why would law be treated differently by the regional accreditators?

Remember while the program is accredited by the ABA, the university is accredited by the regional accreditor, who is going to say that X% of the faculty lack terminal degrees.

UCLA is not in danger of losing their accreditation because they graduate too many JDs and not enough PhDs.

You are correct in your assertion, but have missed the actual point on what accreditors *are* doing. Accreditors care about the DEGREES HELD BY THE FACULTY. In other words, they have concerns that a "mere" R.N. is not qualified to teach nursing and a "mere" M.D. is not qualified to teach pharmacology. Though the schools could argue with their accreditor, it's explensive and there's not a great legal basis on the schools' sides to challenge the accreditator's imposed standard--it's easier to just go along and only hire faculty with a terminal degree.

It's worse than that -- they rehect people with Master's degrees -- i.e. MSN teaching Nursing or MBA teaching accounting. The worst part of this is that most of the people with Master's degrees have real experience in the field.

J.D. is a terminal degree, and is a doctorate.

When I hear the name Bernard Meltzer I think of the comforting voice of the old guy who gave advice, financial and personal, on WOR Radio when I was growing up.

Captcrisis,

I can still hear his voice in my head when I go to bed.

Me also, sometimes, speaking from the little 6-transistor radio on my pillow.

Thanks, Orin. I would draw a connection between your two observations.

(As an aside, I'm surprised at the high-Ph.D numbers. Maybe those with doctorates are being unevenly distributed (which makes some sense), but I've only seen a handful of such candidates coming through my school on interviews in recent years. Lots of fellowships, though.)

Apart from this, I think the real dynamic is that the expansion of "practical" faculty you describe has made schools feel freer to indulge their appetites for "non-practical" faculty, whose interests and scholarship likely diverge from the workaday concerns of most lawyers in practice. After all, if the "practical" teaching were being done by podium faculty, the sorts of people likely best at that task would be different from the sorts of people great at writing dense tracts attempting to provide a Kantian analysis of Bulgarian evidence law, a topic which Orin the thing or two about.

At least, that's been my own sense. But there's a caveat, that perhaps cuts both ways. Taking part in Appointments matter for the first time in years recently, I was struck by how many candidates - regardless of teaching interests - were invested in the "scholar-advocate" model. That is (for example): "I'm writing about X issue in Con Law because I hope to change the law in accord with certain values I hold."

You can guess from what direction those values emanate, and while not generally my own, that is a separate matter.

If this new model is as widespread as my unscientific sample suggests, we may entering a new era of scholarly engagement with the law (mostly directed to "movement" lawyers appearing before courts and legislatures), in which "non-practical" faculty are in fact intensely focused on achieving real-world changes, rather than merely providing analysis of phenomena that, however influential they may become, are not expressly centered on advocacy.

Whether this is good or bad is worth thinking about. But in any event, it complicates our understanding of the current relationship between the academy and law practice.

Thanks for posting, Orin.

I graduated law school 2004 and went to a downtown Chicago law school. Perhaps because it was in a large city, our school had 'connections' to many prominent law firms to get practicing attorneys to come in to teach various classes/seminars. My 1L year (seminar type classes) every professor was a grad of an ivy. By time I got to second semester 2L and into 3L and could pick some electives, I got non-tenured practicing attorneys in whatever field the class was about. My legal writing professor was a practicing assistant attorney general (in the appellate division). My secured transactions professor was a partner at a major international firm whose practice was dedicated to that field of law.

I think a mix is great. I don't want to take a criminal procedure class with someone who has never represented a defendant (or prosecuted one) in court. Anybody (lawyer or not) can read US SUP CT decisions. Applying them to real world examples that we could encounter upon our graduation made it more interesting. My federal criminal law professor was a retired assistant US Attorney (prosecutor) for the northern district of Illinois. He had 100s of trials under his belt. When they speak on a topic and can bring in real life examples from their days practicing it in real life with real lives at stake, it adds a level of authenticity or maybe interest that you wouldn't get otherwise.

Do I need that for every class? No of course not. Especially the 1L courses where we were just learning how to be law students, how to read opinions and analyze them etc... But once the basics were done, give me someone who both knows it, and did it. Much more enjoyable experience.

I am an adjunct professor at a T25 law school, and have been doing that part time for 6 years. I have not observed any changes over that period, but I spend the vast majority of my time not on or near campus. My sense is that adjuncts have little integration with real professors, although I’m sure we have some responsibility in that. None of my scholarship has been through or by the law school.