The Volokh Conspiracy

Mostly law professors | Sometimes contrarian | Often libertarian | Always independent

Today in Supreme Court History: November 21, 1926

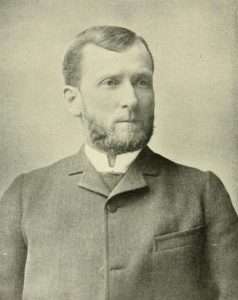

11/21/1926: Justice Joseph McKenna died.

Editor's Note: We invite comments and request that they be civil and on-topic. We do not moderate or assume any responsibility for comments, which are owned by the readers who post them. Comments do not represent the views of Reason.com or Reason Foundation. We reserve the right to delete any comment for any reason at any time. Comments may only be edited within 5 minutes of posting. Report abuses.

Please to post comments

Bank of Marin v. England, 385 U.S. 99 (decided November 21, 1966): bank which had no notice of bankruptcy proceeding not required to turn over to trustee amounts of checks drawn by bankrupt pre-petition but honored post-petition (everything had been squared away with the payee so at issue was only the imposition of costs)

New York, New Haven & Hartford R.R. Co. v. Henagan, 364 U.S. 441 (decided November 21, 1960): Woman stepped in front of train in attempt to commit suicide; train came to sudden stop and waitress in dining car was injured by the jolt (soft tissue injuries plus “paranoid psychosis”). The Court here affirms judgment for the railroad. (P.S. Train did not stop in time.)

State of Washington v. Kuykendall, 275 U.S. 207 (decided November 21, 1927): towing of logs across Puget Sound met statutory definition of “common carrier” even if not registered as such and therefore can only charge scheduled rates even though rate for this job was set by contract between it and private party

If the train did not stop in time, it was probably not just an attempt to commit suicide.

True! I suppose I was trying to create suspense.

McKenna was the third Catholic appointed to the Court after Roger Taney and Edward Douglass White. When President McKinley appointed him in 1898, he joined Justice White on the bench, marking the first time two Catholics were on the Court at the same time. (The current Court has six Catholic justices). He was also the last justice appointed in the 19th century.

McKenna delivered the opinion in the Mutual Film case, which said movie censorship was OK because movies weren’t part of the press protected by the constitution of Ohio (and this was understood as applying by extension to other constitutional free-press provisions, including the First Amendment).

“[Movies’] power of amusement, and, it may be, education, the audiences they assemble, not of women alone nor of men alone, but together, not of adults only, but of children, make them the more insidious in corruption by a pretense of worthy purpose or if they should degenerate from worthy purpose. Indeed, we may go beyond that possibility. They take their attraction from the general interest, eager and wholesome it may be, in their subjects, but a prurient interest may be excited and appealed to. Besides, there are some things which should not have pictorial representation in public places and to all audiences. And not only the State of Ohio, but other states, have considered it to be in the interest of the public morals and welfare to supervise moving picture exhibitions. We would have to shut our eyes to the facts of the world to regard the precaution unreasonable or the legislation to effect it a mere wanton interference with personal liberty….

“…It cannot be put out of view that the exhibition of moving pictures is a business, pure and simple, originated and conducted for profit, like other spectacles, not to be regarded, nor intended to be regarded by the Ohio Constitution, we think, as part of the press of the country, or as organs of public opinion. They are mere representations of events, of ideas and sentiments published and known; vivid, useful, and entertaining, no doubt, but, as we have said, capable of evil, having power for it, the greater because of their attractiveness and manner of exhibition. It was this capability and power, and it may be in experience of them, that induced the State of Ohio, in addition to prescribing penalties for immoral exhibitions, as it does in its Criminal Code, to require censorship before exhibition, as it does by the act under review. We cannot regard this as beyond the power of government.”

https://supreme.justia.com/cases/federal/us/236/230/

Needless to say, that didn't last ("only" for about 37 years). It was overruled in Joseph Burstyn, Inc. v. Wilson, 343 U.S. 495 (1952).