The Volokh Conspiracy

Mostly law professors | Sometimes contrarian | Often libertarian | Always independent

Can a Controversial User Really Get Kicked off the Internet?

In theory, yes; in practice, perhaps soon.

(This post is part of a five-part series on regulating online content moderation.)

When it comes to regulating content moderation, my overarching thesis is that the law, at a minimum, should step in to prevent "viewpoint foreclosure"—that is, to prevent private intermediaries from booting unpopular users, groups, or viewpoints from the internet entirely. But the skeptic—perhaps the purist who believes that the state should never intervene in private content moderation—might question whether the threat of viewpoint foreclosure even exists. "No one is at risk of getting kicked off the internet," he might say. "If Facebook bans you, you can join Twitter. If Twitter won't have you, you can join Parler. And even if every other provider refuses to host your speech, you can always stand up your own website."

In my article, The Five Internet Rights, I call this optionality the "social contract" of content moderation: no one can be forced to host you on the internet, but neither can anyone prevent you from hosting yourself. The internet is decentralized, after all. And this decentralization prevents any private party, or even any government, from acting as a central choke point for online expression. As John Gilmore famously said, "The Net interprets censorship as damage and routs around it."

But while this adage may have held true for much of the internet's history, there are signs it may be approaching its expiration date. And as content moderation moves deeper down the internet stack, the social contract may be unraveling. In this post, I'll describe the technical levers that make viewpoint foreclosure possible, and I'll provide examples of an increasing appetite to use those levers.

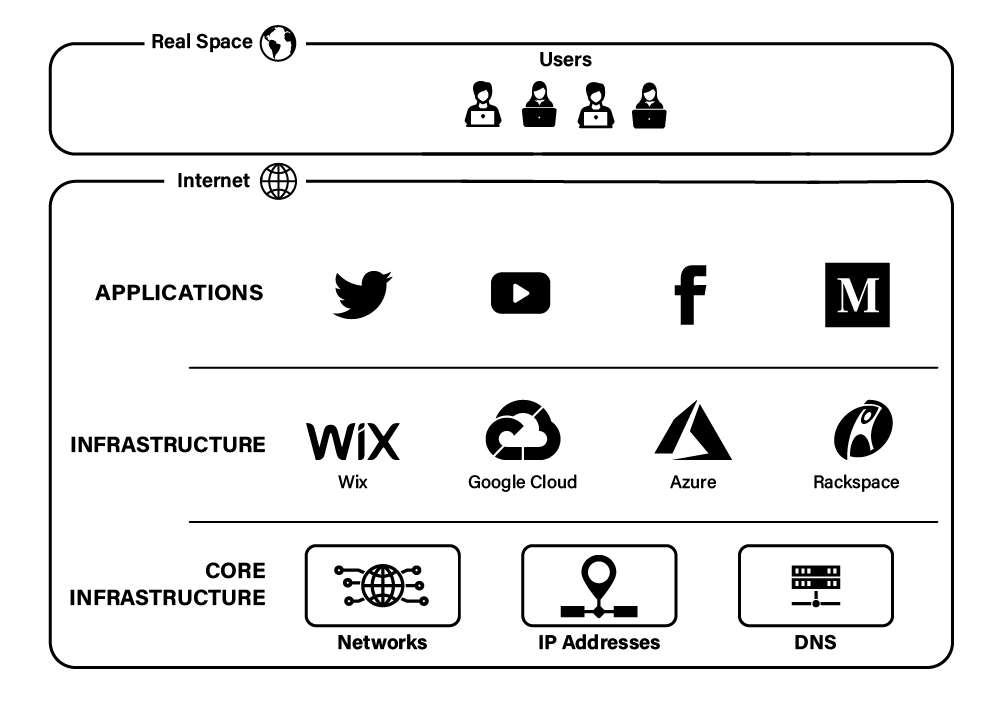

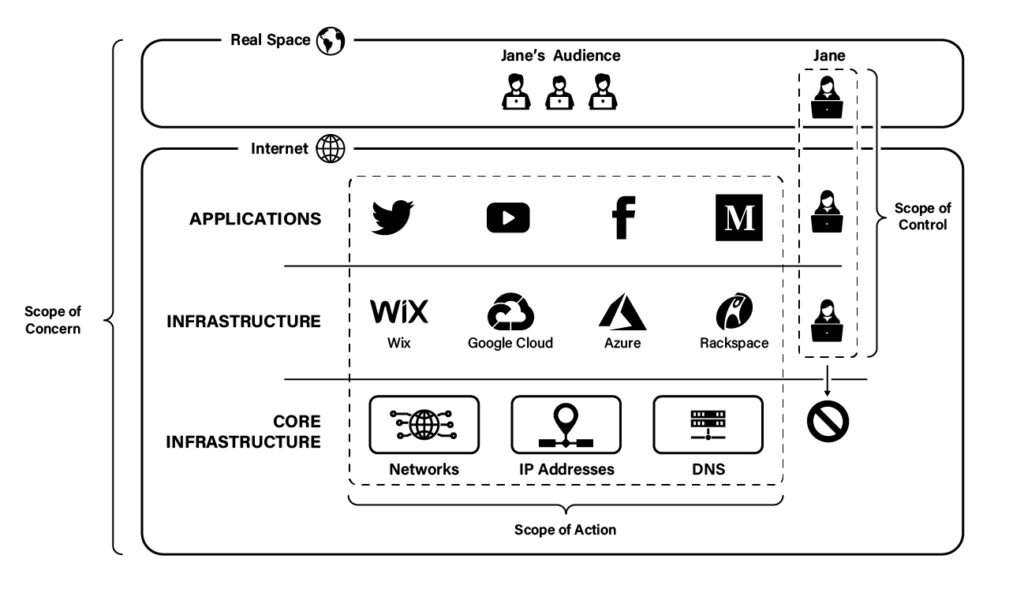

To illustrate these concepts, it's helpful to think of the internet not as a monolith but as a stack—a three-layer stack, if you will. At the top of the stack sits the application layer, which contains the universe of applications that make content directly available to consumers. Those applications include voice and video calling services, mobile apps, games, and, most importantly, websites like Twitter (X), YouTube, Facebook, and Medium.

But websites do not operate in a vacuum. They depend on infrastructure, such as computing, storage, databases, and other services necessary to run modern websites. Such web services are typically provided by hosting and cloud computing providers like WiX, Google Cloud, Microsoft Azure, or Rackspace. These resources form the infrastructure layer of the internet.

Yet even infrastructural providers do not control their own fate. To make internet communication possible, such providers depend on foundational resources, such as networks, IP addresses, and domain names (DNS). These core resources live in the bottommost layer of the internet—the core infrastructure layer.

The below figure depicts this three-layer model of the internet.

With this structure in mind, we now turn to content moderation. As we'll see, content moderation has evolved (and thereby become more aggressive and more concerning) by capturing more real estate within the internet stack. In the following discussion, I divide that evolution into four primary stages: classic content moderation, deplatforming/no-platforming, deep deplatforming, and viewpoint foreclosure. And to make the concepts relatable, I'll use a running case study of a fictional internet user who finds herself a victim of this evolution as she is eventually chased off the internet.

With this structure in mind, we now turn to content moderation. As we'll see, content moderation has evolved (and thereby become more aggressive and more concerning) by capturing more real estate within the internet stack. In the following discussion, I divide that evolution into four primary stages: classic content moderation, deplatforming/no-platforming, deep deplatforming, and viewpoint foreclosure. And to make the concepts relatable, I'll use a running case study of a fictional internet user who finds herself a victim of this evolution as she is eventually chased off the internet.

Classic Content Moderation

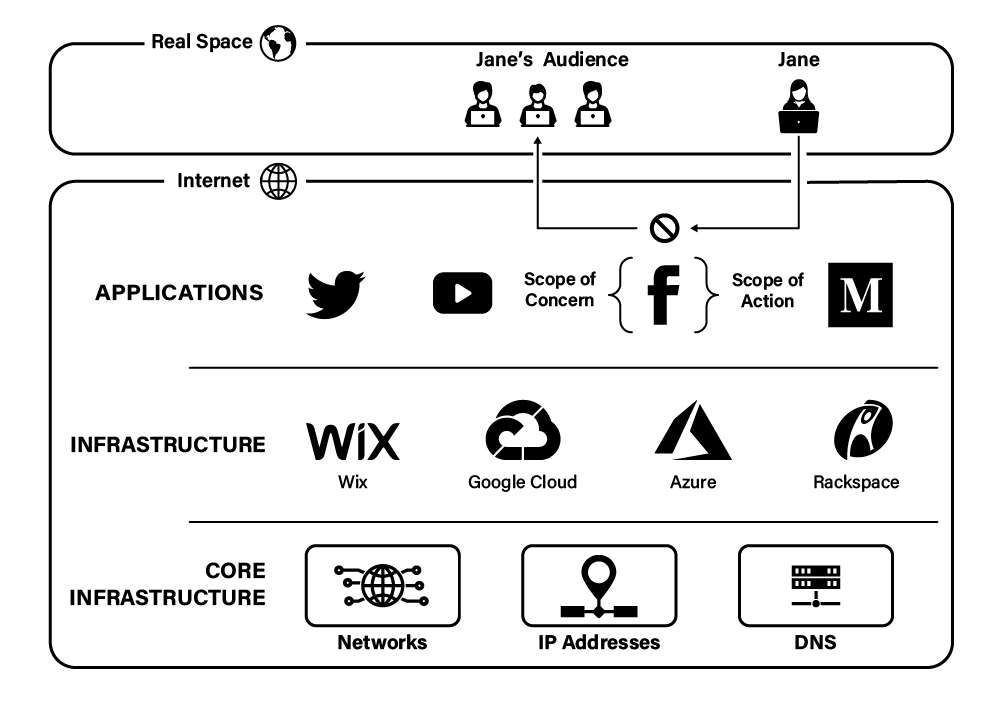

In the typical, classic scenario, when a website takes adverse action against a user or her content, it does so because the user has violated the provider's terms of service through her onsite content or conduct. For example, if a user—let's call her "Jane"—posts an offensive meme on her timeline that violates Facebook's Community Standards, Facebook might remove the post, suspend Jane's account, or ban her altogether.

Here we see classic content moderation in action, as defined by two variables: (1) the scope of concern and (2) the scope of action. At this point, Facebook has concerned itself only with Jane's conduct on its site and whether that conduct violates Facebook's policies (scope of concern). Next, having decided that Jane has violated those policies, Facebook solves the problem by simply deleting Jane's content from its servers, preventing other users from accessing it, or terminating Jane's account (scope of action). But importantly, these actions take place solely within Facebook's site, and, once booted, Jane remains free to join any other website. Thus, as depicted below, classic content moderation is characterized by a narrow scope of concern and a narrow scope of action, both of which are limited to a single site.

Deplatforming / No-Platforming

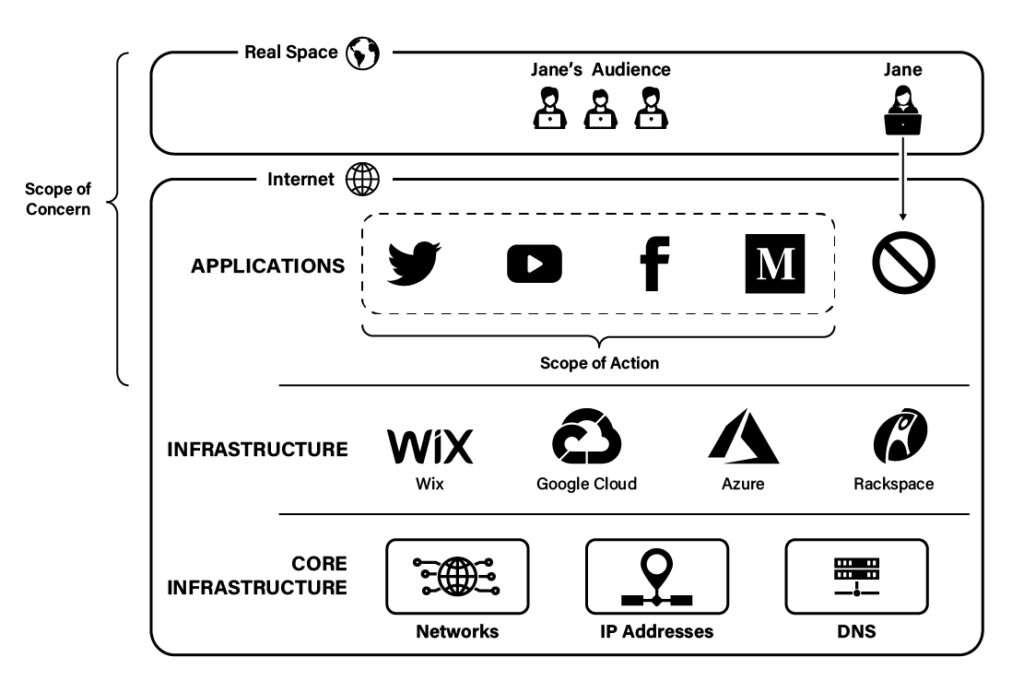

If Jane is an obscure figure, then the actions against her content might stop at classic content moderation. Even if Facebook permanently suspends her account, she can probably jump to another site and start anew. But if Jane is famous enough to create a public backlash, then a campaign against her viewpoints may progress to deplatforming.

As one dictionary put it, to "deplatform" is "to prevent a person who holds views that are not acceptable to many people from contributing to a debate or online forum." Deplatforming, thus, targets users or groups based on the ideology or viewpoint they hold, even if that viewpoint is not expressed on the platform at issue. For example, in April 2021, Twitch updated its terms of service to reserve the right to ban users "even [for] actions [that] occur entirely off Twitch," such as "membership in a known hate group." Under these terms, mere membership in an ideological group, without any accompanying speech or conduct, could disqualify a person from the service. Other prominent platforms have made similar changes to their terms of service, and enforcement actions have included demonetizing a YouTube channel after its creators encouraged others (outside of the platform) to disregard social distancing, suspending Facebook and Instagram accounts for those accused (but not yet convicted) of offsite crimes, and banning a political pundit (and her husband) from Airbnb after she spoke at a controversial (offline) conference. Put differently, deplatforming expands the scope of concern beyond the particular website in which a user might express a disfavored opinion to encompass the user's words or actions on any website or even to the user's offline words and actions.

Moreover, in some cases, the scope of action may expand horizontally if deplatforming progresses to "no-platforming." As I use the term, no-platforming occurs when one or more third-party objectors—other users, journalists, civil society groups, for instance—work to marginalize an unpopular speaker by applying public pressure to any application provider that is willing to host the speaker. For example, Jane's detractors might mount a Twitter storm or threaten mass boycotts against any website that welcomes Jane as a user, chasing Jane from site to site to prevent her from having any platform from which to evangelize her views. As depicted below, the practical effect of a successful no-platforming campaign is to deny an unpopular speaker access to the application layer altogether.

Deep Deplatforming

"But Jane couldn't be booted entirely from the application layer," you might say. "Surely some website out there would be willing to host her viewpoints. Or, worst case, she could always stand up her own website."

As long as content moderation remains confined to the application layer, those sentiments are indeed correct. They capture the decentralized nature of the internet and the putative ability of any enterprising speaker to strike out on her own.

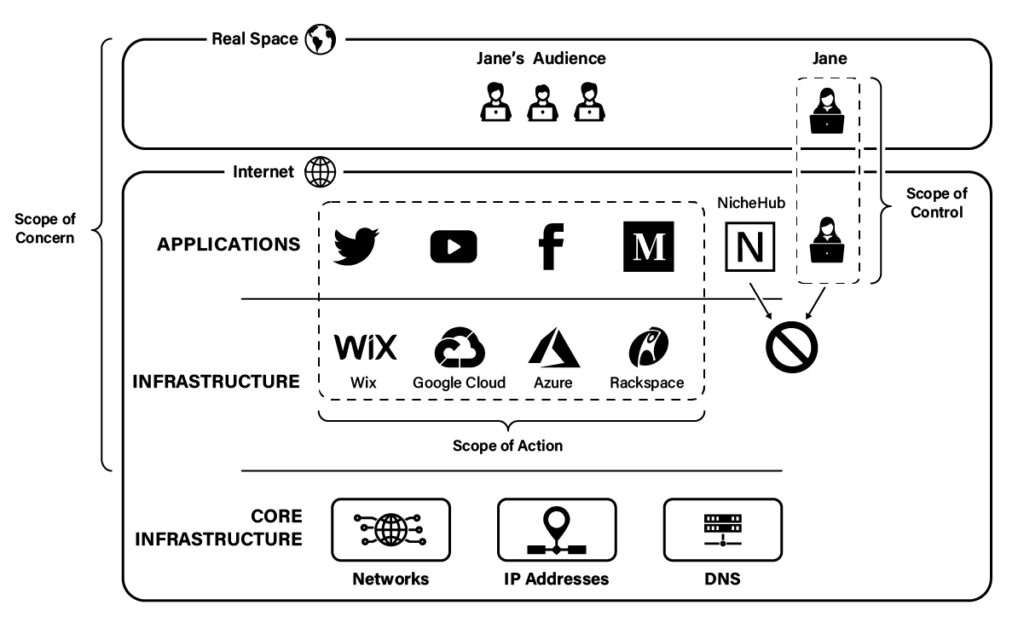

But they become less true as content moderation expands down into the infrastructure layer of the internet. As explained above, that layer contains the computing, storage, and other infrastructural resources on which websites depend. And because websites typically rely on third-party hosting and cloud computing vendors for these resources, a website might be able to operate only if its vendors approve of what it permits its users to say.

Thus, even if Jane migrates to some website that is sympathetic to her viewpoints or that is simply free speech-minded—"nichehub.xyz" for purposes of this case study—NicheHub itself might have dependencies on WiX, Google Cloud, Microsoft Azure, or Rackspace. Any of these providers can threaten to turn the lights out on NicheHub unless it stops hosting Jane or her viewpoints. Similarly, if Jane decides to stand up her own website, she might be stymied in that effort by infrastructural providers that refuse to provide her with the hosting services she needs to stay online.

These developments characterize "deep deplatforming," a more aggressive form of deplatforming that uses second-order cancelation to plug the holes left by conventional techniques. As depicted below, deep deplatforming vertically expands both the scope of concern and the scope of action down to encompass the infrastructure layer of the internet stack. The practical effect is to prevent unpopular speakers from using any websites as platforms—even willing third-party websites or their own websites—by targeting those websites' technical dependencies.

Perhaps the best-known instance of deep deplatforming concerned Parler, the alternative social network that styled itself as a free speech-friendly alternative to Facebook and Twitter. Following the January 6 Capitol riot, attention turned to Parler's alleged role in hosting users who amplified Donald Trump's "Stop the Steal" rhetoric, and pressure mounted against vendors that Parler relied on to stay online. As a result, Amazon Web Services (AWS), a cloud computing provider that Parler used for hosting and other infrastructural resources, terminated Parler's account, taking Parler, along with all its users, offline.

The above figure also introduces a new concept when it comes to evading deplatforming: the scope of control. As long as Jane depends on third-party website operators to provide her with a forum, she controls little. She can participate in the application layer—and thereby speak online—only at the pleasure of others. However, by creating her own website, she can vertically extend her scope of control down into the application layer, thereby protecting her from the actions of other website operators (though not from the actions of infrastructural providers).

Viewpoint Foreclosure

"Ah, but can't Jane simply vertically integrate down another layer? Can't she just purchase her own web servers and host her own website?"

Maybe. Certainly she can from a technical perspective. And doing so would remove her dependency on other infrastructural providers. But servers aren't cheap. They're also expensive to connect to the internet, since many residential ISPs don't permit subscribers to host websites and don't provide static IP addressing, forcing self-hosted website operators to purchase commercial internet service. And financial resources aside, Jane might not have the expertise to stand up her own web servers. Most speakers in her position likely wouldn't.

But even if Jane has both the money and the technical chops to self-host, she can still be taken offline if content moderation progresses to "viewpoint foreclosure," its terminal stage. As depicted below, viewpoint foreclosure occurs when providers in the core infrastructure layer revoke resources on which infrastructural providers depend.

For example, domain name registrars, such as GoDaddy and Google, have increasingly taken to suspending domain names associated with offensive, albeit lawful, websites. Examples include GoDaddy's suspension of gab.com and ar15.com, Google's suspension of dailystormer.com, and DoMEN's suspension of incels.me.

ISPs have also gotten into the game. In response to a labor strike, Telus, Canada's second-largest internet service provider, blocked subscribers from accessing a website supportive of the strike. And in what could only be described as retaliation for the permanent suspension of Donald Trump's social media accounts, an internet service provider in rural Idaho allegedly blocked its subscribers from accessing Facebook or Twitter.

But most concerning of all was an event in the Parler saga that received little public attention. After getting kicked off AWS, Parler eventually managed to find a host in DDoS-Guard, a Russian cloud provider that has served as a refuge for other exiled websites. Yet in January 2021, Parler again went offline after the DDoS-Guard IP addresses it relied on were revoked by the Latin American and Caribbean Network Information Centre (LACNIC), one of the five regional internet registries responsible for managing the world's IP addresses. That revocation came courtesy of Ron Guilmette, a researcher, who, according to one security expert, "has made it something of a personal mission to de-platform conspiracy theorist and far-right groups."

If no website will host a user like Jane who holds unpopular viewpoints, she can stand up her own website. If no infrastructure provider will host her website, she can vertically integrate by purchasing her own servers and hosting herself. But if she is further denied access to core infrastructural resources like domain names, IP addresses, and network access, she will hit bedrock. The public internet uses a single domain name system and a single IP address space. She cannot create alternative systems to reach her audience unless she essentially creates a new internet and persuades the world to adopt it. Nor can she realistically build her own global fiber network to make her website reachable. If she is denied resources within the core infrastructure layer, she and her viewpoints are, for all intents and purposes, exiled from the internet.

While Parler did eventually find its way back online, and even sites like Daily Stormer have managed to evade complete banishment from the internet, there can be little doubt that the appetite to weaponize the core infrastructural resources of the internet is increasing. For example, in 2021, as a form of ideological retribution, certain African ISPs publicly discussed ceasing to route packets to IP addresses belonging to an English colo provider that had sued Africa's regional internet registry. And in March 2022, perhaps inspired by the above examples, Ukraine petitioned Europe's regional internet registry to revoke Russia's top-level domains (e.g, .ru, .su), disable DNS root servers situated in Russian territory, and withdraw the right of any Russian ISP to use any European IP addresses.

In sum, while users today are not necessarily getting kicked off the internet for expressing unpopular views, there are technical means to do just that. It also seems that we are moving toward a world in which that kind of exclusion may become routine.

Editor's Note: We invite comments and request that they be civil and on-topic. We do not moderate or assume any responsibility for comments, which are owned by the readers who post them. Comments do not represent the views of Reason.com or Reason Foundation. We reserve the right to delete any comment for any reason at any time. Comments may only be edited within 5 minutes of posting. Report abuses.

Please to post comments

There... are... seven... layers!

(I had to work with a standard that followed the OSI seven layer model of networking. An appendix mentioned as an afterthought that one could also use TCP/IP, which is what everybody did in practice.)

The OSI model covers network layers specifically. It's a perfectly useful model but hardly the only way of representing layers on the Internet.

(FWIW, IP sits at layer 3 and TCP at layer 4 in the OSI model; TCP/IP is not a full replacement for the OSI model, which would include technologies like WiFi lower down the stack and HTTP(S) higher up the stack.)

All models are wrong but some models are useful.

The 7-layers model is very useful for understanding information security and a host of highly technical subjects. This simplified 3-layer model probably wouldn't work in those situations but it's plenty adequate for the topic being discussed above. To be blunt, it's going to be a stretch for the author to clearly explain these 3 layers to a non-technical audience (which is, after all, his target). Trying to explain all 7 just to come back to the three he cares about would be an example of pedantry getting in the way of effective communication.

"To be blunt, it’s going to be a stretch for the author to clearly explain these 3 layers to a non-technical audience (which is, after all, his target). Trying to explain all 7 just to come back to the three he cares about would be an example of pedantry getting in the way of effective communication."

Exactly! [Over-]Simplification is often the only way to begin an explanation.

App stores are another chokepoint. If you want your app approved by Apple it should not allow access to undesirable content. Some Ukrainians who wanted their war tracker app approved got in trouble with Apple censors because they called the Russians names. Mostly "кацап", which I think you can say here. The bad words do not need to be in the app. As long as the app allows access to external content with bad words or bad viewpoints it risks removal.

Choke points are the fundamental problem. We've allowed too many to accumulate, all through our society. In the internet, publishing, financial services, you name it.

They accumulated because there was trust, which at one time was actually justified, that they wouldn't be abused, and they did provide a bit of efficiency. But once they existed, they attracted people who saw and treasured the power abusing them provided.

We have to somehow find our way back to social arrangements that provide for fewer choke points. Because it's an established fact:

Choke points WILL be abused.

Brett continues to not believe in markets.

I mean who can believe in markets when there are liberals around to participate in them, liberalishly?

Oh, dear, I'm not as cartoonish as you'd like me to be.

These choke points are taking place in private marketplaces.

You want to dictate to Apple what apps it allows. Because liberals gonna use it for evil.

You don't believe in free markets. You're fully advocating for the old definition of conservativism: "Conservatism consists of exactly one proposition, to wit: There must be in-groups whom the law protects but does not bind, alongside out-groups whom the law binds but does not protect."

Historically, both progressives and conservatives have been concerned about accumulations of private power, not just state power. Hence we have legal rules and doctrines regarding antitrust and monopolies, common carriers, antidiscrimination, etc. It's dishonest and childish to say that all the thinkers who created those and other such doctrines "didn't believe in free markets": they believed that markets required regulation, by legislation or common law, to ensure that they served the common interest.

Yeah, liberals are down with regulated markets as creating the environment for markets to function best, like muscular antitrust, etc.

Conservatives aren't.

This isn't about the market functioning properly, this is about the market not giving conservatives what they want so they're gonna force it to.

That kind of pinpoint outcome-orientation is well beyond where any liberals are, much less 'the party of small government.'

LOL. If you want to believe that progressives only regulate to prevent genuine instances of market failure based on theoretically sound analyses, whereas conservatives are "outcome-oriented," go ahead, but no one takes you seriously.

There’s some on the left who hate markets and want communism.

Leaving them aside, the liberal consensus is that markets are good, capitalism is good, but 1) markets are not good for all applications, and 2) markets need some regulatory structure in which the function for them to deliver.

Conservatives supposedly like markets in most places, and think deregulation is what you need to set markets awhirlin'.

But here, and increasingly, conservatives don't like how the market is doing stuff they don't like. Not failing, or providing efficiency when you want equity, or anything like that. They don't like the market's operation and want to forbid certain specific market operations, and pretend that's fixing the market.

No one is fooled; this is just another sign of the right's discarding democracy and liberty for authoritarianism 'in service of returning liberty.'

Let me get this straight: Perfectly fine to force a single proprietorship to provide service, involuntarily, to a client they don't want to serve, when they could just go next door for their damn cake.

But how dare we not permit megacorps to collude in denying particular people service? The horror!

Yes, refusing to serve blacks or gays is not the same as refusing to serve Nazi assholes.

One refusal to serve is based on prejudice against someone you have never met.

The other is based on actual individualized past experience with said asshole being an asshole you don't want to be associated with.

Alleged</i< Nazi assholes. We all know the left's definition of "Nazi": "Anyone I'd like to punch."

As soon as Nazi assholes lose their rights, everybody those in power don't like become 'Nazis'.

It’s more the asshole than the Nazi. Twitter banned plenty of assholes on the left as well. As I said, it's not about being part of a class of people. Twitter bans were about individualized actions.

That is the distinction between prejudice and disassociation.

The Nazi part is because that is specifically who you seem concerned about.

LOL. "groomers."

An excellent description of what's going on, on a technical level. I might quibble with this:

"In the typical, classic scenario, when a website takes adverse action against a user or her content, it does so because the user has violated the provider's terms of service through her onsite content or conduct."

TOS are written sufficiently vaguely, and enforcement is sufficiently lacking in anything resembling due process, that invocation of the TOS is often just a formality hiding an entirely arbitrary decision.

Moderation of content is a thankless job which most normal people stay well away from, so it has largely ended up the domain of what can best be described as "professional busybodies"; The sort of people who actually enjoy exercising the power to force people they dislike or disagree with to STFU.

I'm not saying that there isn't any real TOS enforcement out there. But the real issue is just arbitrary censorship that is masking itself as TOS enforcement.

Sounds like DMV employees.

I wrote about the LACNIC example in yesterday's comments. I don't think it supports the notion that IP registries are engaging in deplatforming or content moderation. Rather, as Professor Nugent notes, there's a specific researcher trying to deplatform Parler and others, and he discovered that DDos-Guard was registered in Belize as a ruse to get IP addresses from LACNIC as opposed to legitimately doing business there. He reported this rules violation (based on the fact that DDos-Guard operated out of Russia rather than Latin America) and got their IP addresses revoked, but it really had nothing to do with Parler or its content.

Having said that, I remain sympathetic to the notion that lower-layer infrastructure providers shouldn't be allowed to terminate service based on legal but controversial content and I doubt that the providers would hate such a mandate since they wouldn't have to dedicate energy to making judgment calls in these situations.

I think Nicholas understands this, which explains why he doesn’t expressly describe LACNIC’s decision to boot Parler as based on that platform’s intentionally being designed to enable and foster domestic terrorism. He instead points to the motivations of the person who highlighted Parler’s subterfuge.

The more we’re seeing from Nicholas, the less reason we have to believe he’s engaging in good faith. His initial framework was theoretically suspect, his first substantive post included fatal obfuscation, and in this post he feels no need to avoid value-laden terminology or to accurately describe the “de-platforming” examples he chooses to cite. He’s also continuing the pattern of beginning every discussion of “viewpoint disclosure” with a long digression into content moderation on the “app level,” which (for a certain target audience) is a way of priming the intuition pump to lead to a particular conclusion.

When Nicholas first started posting here, I was impressed that the VC managed to find a contributor who had actually spent some time practicing in the real world - and who, moreover, achieved the difficult task of transitioning from an in-house role to academia. I had hoped to read the contributions of someone with an intense passion for intellectual rigor and academic discourse. It is disappointing to find that he may be, in actuality, just another hack with an axe to grind - one who happens to agree with Eugene.

If I have any complaint about his description of the deplatforming of Parler, it's that he makes it sound too benign, omitting any discussion of the way they got hit almost simultaneously from multiple directions, by nominally independent services cutting them off in what looked a lot like a coordinated takedown.

Yes, Brett, I think we’re all aware of the way right wingnuts like yourself perceive “bias” whenever someone fails to speak to your narrow grievances.

The Krebs piece that Prof. Nugent links to is actually pretty interesting. It might be reasonable to think about the Parler takedown as being "coordinated" but not in the way you think. Rather than execs meeting in a smoke-filled room and deciding to take down Parler because they hate conservatives, it turns out there was a single researcher running around looking to make trouble for Parler, apparently with quite a bit of success!

I think it's fair to say that he had quite a bit of success because they hated conservatives, though. He was trying to roll a stone downhill...

He'd have had an uphill battle if his target had been notably left-wing.

The content on Parler was rancid. In the days leading up to the deplatforming event, it was filled with racism, antisemitism, homophobia, pornography (that intermixed with all of the above), and calls to violence. There were lawsuits by Parler against AWS and plenty of discovery and evidence for anyone interested in those details.

You’re saying people took action to distance themselves and their private firms from this because “they hated conservatives?” If so, then your definition of conservative is pretty radical.

The reason they did it was the lack of censoring of conservatives. Literal porn sites had less trouble with this sort of thing.

If all this is really a problem, it can be solved at a stroke. Outlaw after-publication takedowns and edits by third parties. Replace them with private editing prior to publication. Except among internet utopians—admittedly a dauntingly large and vehement cohort—prior editing is uncontroversially practiced at level one, and not practiced at other levels. So the lower level functions will escape meddling. Problem solved. To do it, just repeal Section 230.

But by the way, so far unmentioned has been the subject of government activities which routinely attack the lower layers of communications infrastructure to maximize the efficiency of vacuuming up user content and storing it all, just in case.

Riiight. Turn every platform into a newspaper. Count on you to come up with that stupid idea.

But,

"But by the way, so far unmentioned has been the subject of government activities which routinely attack the lower layers of communications infrastructure to maximize the efficiency of vacuuming up user content and storing it all, just in case."

This is the sort of reason why I've never been tempted to mute you. You're right on target about that.

In fact, I suspect this is why SpaceX's Starlink is under attack: In principle, once the constellation is in place, you could totally and completely bypass all those points where the surveillance state vacuums up content. DNS lookups, website hosting, switches, EVERYTHING can be handled by Starlink, the only ground infrastructure it will ultimately need is the individual user terminals.

Government faces a nightmare scenario of end to end encryption with the physical packet handling outside its reach. No wonder Musk faces so much regulatory interference!

Setting aside the fact that trading the government for Musk is likely not an improvement... "EVERYTHING," cannot be handled by Starlink. Musks constellation doesn't have a long lifespan, either. Musks sky full of routers works great as long as they continue to get government permits to launch or barring private or government attempts to withhold necessary resources (like IP addresses).

I'm not saying that the government couldn't shut Starlink down by acting against Musk on the ground. I'm saying that the full implementation of Starlink offers them no convenient points at which they can tap/block communications.

Not like ground based internet, where the major switching centers are literally built with hardware dedicated to government spying.

L, as they say, OL.

What theory of the first amendment would permit that?

In short, give all the power back to Lathrop and his cronies.

Lathrop deems everyone except himself to be an "Internet utopian." But of course the irony is that the exact opposite is true. Everyone except Lathrop understands that the Internet has tradeoffs, and Lathrop's real problem is that he doesn't like the tradeoffs that everyone else on the planet does. So he pretends that all problems would be solved if we would just adopt his archaic and failed 19th century model.

maybe to the hacker collective “anonymous” rebrands as “Jane”?

Well, which is it, facetious power mongers? Common carrier, so you can regulate it, or private bozos who can kick you off?

False dichotomy. Could be both depending on the layer.

It's just a guess but I'm going to predict that the author will argue for common carrier (or some equivalent) for the core infrastructure layer and maybe for the infrastructure layer but private entities for the applications layer.

Given his posts so far this week, that absolutely seems to be where he's going. And I think that's right (at least outside a truly libertarian world where the market is solely self-regulating). A DNS is not a publisher/distributor like social media companies are.

Agreed. I find the line of argumentation a lot more supportable than Professor Volokh's arguments that we should treat the social media platforms as common carriers.

I am wary of laws that purport to regulate content moderation by owners of web sites.

I have posted in comments on other blogs the ethics of content moderation. But a law that, for example, was meant to guarantee free speech on X could easily be applied to require Holocaust education web sites to allow posts and comments denying the Holocaust on comments sections and discussion forums that it hosts.

I do concur with DNS. The people in charge of core infrastructure have absolutely no business regarding the content of web sites.

Suppose all pharmacies refuse to sell a drug to a patient who needs it to survive. The reason is that the pharmacies trace their customers' online activity and it turns out that this person spreads what the companies deem "hateful speech" that they believe imperils others. In principle, this is perfectly legal, and not out of the realm of possibility, given the nature of our public world. Now imagine grocery stores, mechanics, banks, colleges etc. all do this. You could--without the assistance of government--literally starve and kill a person, deprive him of investment earnings, under this libertarian nightmare, one in which only private parties are involved.

This, of course, raises the question of whether the consortium of private entities has--by their conspiring--become a "de facto" government: they have absolute power, pass laws, and exercise police powers.

The old public/private model is obsolete.

This is the sort of topic that was routinely discussed among libertarian theorists back when I joined the movement in the 70's. It's clear that nominally 'private' organizations can take on enough of the character of government that they can't really be considered private anymore, especially as they approach monopoly status, or coordinate with other market players.

Try Theodore Roosevelt. He was very concerned some business operations got so large they wielded power properly only wielded by democracy.

I would add, "...if even that." Outside war.

Anyway, when government threatens media companies worth more than the Big 3 with laws (or repeals) that will massively reduce them, it is hardly private entities freely exercising choice to ban those the politicians want.

Yes, twitter is basically a life-saving drug.

Gaslighto, as a bureaucrat, you really ought to understand this.

I have a prescription for Antibiotic A which has been prescribed to be electronically by my MD. But because it doesn't like what I post on Twatter and Farcebook, Walgreens computer deletes it. As does CVS's. As then do those of the various grocery store pharmacies and WalMart. Who's left?

There AREN'T any independent pharmacies anymore.

Ed doesn't get Antibiotic A...

Ah yes insane hypotheticals nowhere near happening as though this is a crisis.

Yeah, Ed, I understand what your posts are about. Better than you do, I think.

Isn't this pretty much what the Chinese "Social Credit" system is all about?

Pretty much. A lot of left wing activists in government AND private industry think their Social Credit system is very nifty, and are trying to implement it here, too, via the back door.

Literally the only people talking about social credit are right wingers.

I didn't say they were openly talking about it, I said they were doing it.

Another sekret liberal agenda with zero actual evidence! Add another to the Brett counter!

Is this observation before or after NY warned banks to be careful servicing gun companies lest it tarnish their reputation, and they lose state business?

And a "social credit" system does not become any more morally acceptable if the people or entities imposing it are in the private sector. As such entities as Visa and PayPal are already trying to do by denying dissidents access to the banking system. If existing anti-monopoly facilities such as the anti-trust authorities are unwilling to categorically prevent any such denial, then it is morally imperative that courts do so.

One of my longtime Usenet allies, Christopher Charles Morton, wrote this on another discussion forum.

https://forum.pafoa.org/showthread.php?t=379059&p=4499368#post4499368

- Chris, dba Deanimator

Chris makes a very good point. If people are being excluded from the almost limitless number of transactions and endeavors that constitute ordinary civic life in a free society, what do they have to lose by killing those who are excluding them?

I am certain this sort of thing was practiced against civil rights activists in the 1950's and 1960's, and we are lucky there was no retaliatory violence.

Imagine if a sopcial credit system existed during the Jim Crow era.

Um, it did. Are you unaware that black people who tried to register to vote (let alone actually voting!) would find themselves denied employment, bank loans, etc.?

I agree that "The old public/private model is obsolete" but the most ancient one is not. Stopping the discussion of libertarian theory in the 1970s would omit valid libertarian points made by Karl Marx (https://twitter.com/goldman/status/1108778703671062529) regarding the fact that every form of socialism ultimately demands authoritarianism: while it's heartening to believe that "sharing is caring," in practice sharing is both an invitation for and a means of command and control. The antibiotic example (and the automobile example farther below) are appropriate and to some degree lead to the conclusion that there must be some level of necessary interoperability intrusion into which is verboten and protection of which is mandated.

The Roman law doctrine of trinoda necessitas continues to apply and continues to be controversial: the practical requirements of life transcend the usual boundaries of the highest laws and become a "tax though not a tax." (see Butler v. Perry [also Kazminski, Herdon, Immediato, Steirer, etc]). Compulsory public service is not new: some mechanisms of daily life must be maintained and publicly provided even if ordinary rights must be set aside.

I'm pretty sure that you can't prove that reality is bad by inventing a science fiction hypothetical.

An excellent summary of the architecture, roles, and scopes. Another commenter above mentions that technically there are seven layers in the actual Internet, not three, but I think this simplification into just network > platform > application layers is perfectly fine for understanding the issues.

I would only add, as I seem to be doing on every installment in this series, that the deeper one goes into the layers to force someone off the Internet, the more the operators and vendors must intentionally circumvent and subvert the system to do so.

What I mean is that below the top Application layer, it takes an intentional, malevolent act to detect and block specific requests and services, breaking the normal functioning of that service. A database engine, for example, is not supposed to know anything about the politics or practices of the person making the request.

The analogy of a car on a publicly free road is useful. The pavers of the road aren’t supposed to care if “Joe” is driving on it. The car itself isn’t supposed to care, either. To make the car or the road aware of “Joe” so he can be blocked would require the insertion of monitoring and blocking practices and controls that are not needed for normal functioning.

The words we in IT use for this kind of thing are “anti-pattern”, ” dark pattern”, and “malware”. It was understood from the earliest beginnings that people would try to subvert the design of the system.

While that’s true, we’re not mostly seeing lower level attacks on individual users, but instead on institutions on the next rung up that refuse to cooperate in attacks on individual users.

So, the DNS server doesn’t do a detailed inquiry to find out you’re trying to look at a comment on Parler by Bob. It refuses to resolve Parler’s url because Parler won’t take down Bob’s comment, and Joe’s comment, and Earl’s comment.

At the top layer the attacks may target individuals. Further down, the attacks target institutions on the net layer up that refuse to target specific sorts of individuals.

This represents an effort to recruit the entire IT ecology to enforce an ethos of censorship by punishing those who won't play along.

We can draw a different analogy - to the financial system.

As with the internet, we generally want people to have access to banking services and be able to legally transact through it with anyone they please. Also as with the internet, financial institutions should generally be indifferent as to the substance of those underlying transactions. Among other things, that’s why the hubbub over credit card companies being pressured not to transact with gun companies or vendors was such a big deal.

But we do expect banks to comply with sanctions requirements and to not knowingly provide banking services to terrorists - even if the underlying transactions are perfectly lawful. These prohibitions require banks to go out of their way - that is, to engage in “intentional” and “malevolent” acts - to shut certain actors out of the financial system.

Should we revisit the understanding that these kinds of restrictions on financial institutions are acceptable?

The problem here is that "terrorism" is a crime subject to legal adjudication, which quite naturally can carry legally enforceable penalties.

Those legally enforceable penalties can, and typically would be, enforced at the top level of the system. You're denied a credit card by the bank, they don't identify your card transactions and thwart them lower in the system.

What we're talking about here is largely about penalizing wrongthink, not adjudicated crimes.

The financial system is not regulated only or even primarily through the criminal justice system. KYC does not only apply to convicted criminals.

Are you being intentionally or unintentionally obtuse?

Parler wasn’t getting deplatformed for “wrongthink.” It was set up specifically to enable right-wing domestic terrorist networks.

No, I'm intentionally not parroting the excuse they used for shutting down a platform that refused to censor wrongthink.

Show your evidence that was pretext.

The government expects banks to comply with their arbitrary and onerous sanctions requirements. And I imagine some real people do, too. I do not. Banks are not police and the government should not be able to simply coopt them into acting as police. If the government wants to accuse X of a crime, the government should do the hard work of gathering and analyzing the evidence.

Sanctions laws suffer the same disability as tariffs - they most hurt the very people they claim to be about protecting. No, those kinds of restrictions on financial institutions are not acceptable.

I mean, maybe check into what government does in investigating financial crimes.

But libertarians don't tend to like their airy principles to contact reality.

"we generally want people to have access to banking services and be able to legally transact through it with anyone they please."

We all saw what happened to the trucker protesters in Canada.

"I would only add, as I seem to be doing on every installment in this series, that the deeper one goes into the layers to force someone off the Internet, the more the operators and vendors must intentionally circumvent and subvert the system to do so."

It's true that you've said it before, and it's also the case that it continues to be wrong. All the vendors need to do is turn off the service, just like any other utility. The water company doesn't need to do anything complicated to turn off your water; they just close a valve. (And yes, the pipes don't care if you're watering your lawn or making beer or bottling it and selling it as Dasani, but that doesn't change the shutdown mechanism.). Similarly, Amazon just needs to shut down your virtual machines or load balancers, and a DNS provider just needs to withdraw your DNS records. It's true that the further down the stack, the less tailored the remedy (e.g., when LACNIC withdrew DDos-Guard's IP addresses, it affected thousands of other customers) but that's not "circumventing the system".

That doesn't answer the question of whether they SHOULD do these things, but let's have the discussion on the basis of facts not cukoo theories of how the Internet works.

He was obviously assuming a tailored attack aimed at a particular person, which, yeah, depending on the level and location it took place at would require subverting the system, not a blunderbuss, "The target is in NYC, let's take down the whole city's internet service to stop him." style attack.

Sure, if my ISP took a disliking to me, they could disconnect me, and a couple hours later I'd be back online again, because the high speed internet market is absurdly competitive here. I've got three different companies asking for my business.

But if my ISP wanted to keep OTHER people in their customer base from connecting to me after they'd shut off my cable? Kinda tough to do without a subversively detailed look at everybody else's data traffic, which was DaveM's point.

...but no one is doing that* so if that's his point it's also cukoo.

* Other than, apparently, that ISP in Idaho that got mad at Facebook and Twitter and didn't want to let their users access those services.

That’s a good try at rehabilitating DaveM’s point but it’s still wrong. In this analogy, your ISP is not trying to keep other people in their own customer base from connecting to you by monitoring everyone’s direct connections. They are doing it by first cutting off your cable then convincing the other ISPs to not take you on as a customer.

Back to the car example, the road isn’t aware of “Joe” – except that at a billing level, it is. Joe needs to pay a toll to get on the road. The road isn’t aware of Joe while he’s on it but it’s definitely aware of him at the on-ramp. Which illustrates the breakdown in DaveM’s analogy. He starts by postulating a car on a “publicly free” road. Absolutely nothing about the Internet meets that criteria. Every layer in the stack is privately owned and available to you only for fee.

No, I am not assuming a tailored attack on an individual. It could be an attack of any scope. China attacks the entire population of its country. AWS attacked an entire company.

What sets it apart is that it is an attempt to intentionally deny access based on content but doing it at an improper technical level. This is the anti-pattern. It attempts to shoe-horn a targeted denial into a common access resource.

All the vendors need to do is turn off the service, just like any other utility.

I will try this again, since you seem to be having difficulty with the concept. The vendor of a paved roadway is not expected to be able to selectively "turn off" their paving machine. There's just the one road, everyone rolls on it. Similarly, there's just the one Internet behind all these applications. We're all using the same resources such as network connectivity, name resolution, address space, and so on.

You are perhaps confusing the Application layer with these other, lower down resources. From the end users point of view, it does indeed look like access is gated individually. But that is only at the top. Not below it. Below that, it's all like the paved roads: common, public resources.

Again, DaveM, your error is starting from the analogy to a road built with public funds and therefore open to the public without fee. Nothing about the internet matches that description. It's all private infrastructure available to you only for fee or by the grace of the actual property owner. That makes the analogy a toll road rather than a "free" road - and unless you pay strictly with cash (an option not really available for internet transactions), toll road operators very much know who you are.

If the right wing 'make everyone play with us' ends up with net neutrality, I'll be pretty pleased.

Net Neutrality wasn't net neutrality, Sarcastr0. I'm sure you know this and are just doing your thang.

"You private companies cannot hinder streams in favor of your own! But hinder our political opponents a-ok! We daren't unethically stop you!"

I now await the hemming and hawing and threading the tortuous needle to discern a valid chimeral difference in government control good...wait bad...wait good...

I am glad that Nick Nugent explained some of the technology. The Internet is not magic, but suddenly more people are exposed to details of network technology than they have ever been previously. Network layers have been around for a long time. The FCC used to know how to deal with network layers.

Title 47 nowhere mentions Telex. Telex is a telecommunications service and common carriage service which is layered on top of the switched telephone network telecommunications service and common carriage service. The FCC has adequately regulated Telex for almost 100 years.

As I mentioned yesterday, the declaratory sections of 47 U.S. Code § 230 seem to declare the Internet to be a public forum (something on which SCOTUS must rule).

In addition, § 230 (f)(1) tells us that the private and public networks within the Internet are inextricably intertwined. This inextricable intertwining means that a business, which like Facebook operates within the Internet, is inextricably intertwined with the government as “Eagle Coffee Shoppe” was in Burton v. Wilmington Pkg. Auth, 365 U.S. 715, 716 (1961). Thus state action doctrine applies.

Furthermore, 42 U.S. Code § 2000a applies because the Internet belongs to the set of [§ 2000a (b)] "Establishments affecting interstate commerce or supported in their activities by State action as places of public accommodation." The Internet is something established that affects interstate commerce. The Internet is supported by State action AS a place of public accommodation. The statute does not say supported in their activities by State action TO BE places of public accommodation. The statute says "AS places of public accommodation." "AS" indicates a simile. The Establishment need only be metaphorically like or as a place of public accommodation.

We analyze the Internet as we analyze a public drinking fountain.

The public drinking fountain is not a place like a hotel or a restaurant, where a person sits at a table and is served. The public drinking fountain is a valve on a water pipe. The public drinking fountain is an establishment, a facility, or a device just as the Internet is.

The Internet is a place of exhibition or entertainment.

Thus, § 2000a applies to the Internet, and 42 U.S. Code § 2000a (b)(4) applies to every entity within the Internet.

Noah v. AOL Time Warner Inc., 261 F. Supp. 2d 532 (E.D. Va. 2003) was a ridiculous decision. Noah was a pro se litigant, who understood neither the law nor the technology of the Internet.

As I mentioned yesterday, you can't read and you don't understand statutory interpretation. And at some point you just have to accept that when every court tells you that you're wrong, the problem doesn't lie with them.

Feel free to explain the basis on which 42 U.S. Code § 2000a desegregated a public drinking fountain.

The phrase "public drinking fountain" is ambiguous. It could refer to a drinking fountain operated by the government, in which case it would not be a place of public accommodation covered by 2000a. Or it could refer to a privately owned and operated drinking fountain that is open to the public, in which case it would also not be a place of public accommodation, but rather a service or privilege of a place of public accommodation.

SCOTUS may settle the common carriage issue this session. The Solicitor General has recommended that SCOTUS rule on this issue, but SCOTUS does not always listen to the Solicitor General.

Only one poorly argued District Court case [Noah] addresses the CRA Title II issue, and the Court of Appeals merely affirmed.

Please explain how the principle of eiusdem generis applies to a public drinking fountain, which belongs to the set of [§ 2000a (b)] “Establishments affecting interstate commerce or supported in their activities by State action as places of public accommodation.”

Assuming that this is a reference to the twin NetChoice cases, the SG has recommended that SCOTUS grant cert., but not on any spurious "common carrier" issue. (Indeed, other than quoting in passing Judge Oldham's insane opinion that referenced it, the SG doesn't even use the phrase in its brief.)

Of course your claim is incorrect: there are several poorly argued District Court cases that address the CRA Title II [non-]issue, including, of course, Martillo v. Twitter. But the rulings were fine; it was just the plaintiffs that made terrible arguments.