The Volokh Conspiracy

Mostly law professors | Sometimes contrarian | Often libertarian | Always independent

Joke "We Need You Brad Pitt" Post at Start of COVID Pandemic Protected by First Amendment

The post led to the author being arrested for "terrorizing"; so clearly unconstitutional that the police officer lacks qualified immunity, says the Fifth Circuit.

From today's Fifth Circuit decision in Bailey v. Iles, written by Judge Dana Douglas and joined by Judges Patrick Higginbotham and James Graves:

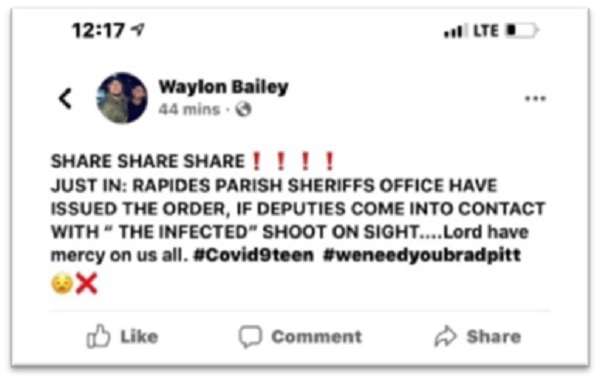

Bailey lives in Rapides Parish in central Louisiana. On March 20, 2020—during the first month of the COVID-19 pandemic—he posted this on Facebook:

Bailey intended the post as a joke and did not intend to scare anyone. The "hashtag" "#weneedyoubradpitt" referenced the zombie movie World War Z, starring Brad Pitt. Bailey included the hashtag to "bring light to the fact that it was a joke." He was bored during the COVID-19 lockdown and used Facebook to keep in touch with friends and "make light of the situation."

Bailey's post was in response to another friend—Matthew Mertens— posting a joke about COVID, and Mertens understood Bailey's post to be a joke. The two continued to post comments underneath Bailey's post. Merterns posted "lol and he [referring to Bailey] talking about my post gonna get flagged � he wins." Bailey posted "this is your fault" and "YOU MADE ME DO THIS." Another person, who Mertens later identified as Bailey's wife, also jokingly commented "I'm reporting you."

Shortly after Bailey posted, Detective Randell Iles was assigned by the Rapides Parish Sheriff's Office (RPSO) to investigate. Iles' supervisors were concerned that the post was a legitimate threat; Iles testified at his deposition that he thought that the post was "meant to get police officers hurt." Iles looked at the post and the comments and concluded that Bailey had committed "terrorizing" in violation of Louisiana Revised Statute § 14:40.1. Iles had no information regarding anyone contacting RPSO to complain about the post or to express fear, or if any disruption had occurred because of the post….

According to Bailey, he was working in his garage when as many as a dozen deputies with bullet proof vests and weapons drawn approached him and ordered him to put his hands on his head, after which Iles told him to get on his knees and handcuffed him. While Bailey was handcuffed, one of the deputies (not Iles) told him that the "next thing [you] put on Facebook should be not to fuck with the police" and the deputies laughed….

In a supplemental investigative report completed after the arrest, Iles recounted that Bailey told him he had "no ill will towards the Sheriff's Office; he only meant it as a joke." Bailey deleted his Facebook post after Iles told him that he could either delete it himself or the RPSO would contact Facebook to remove it….

RPSO announced Bailey's arrest on its own Facebook page, and he was identified in news reports as having been arrested for terrorism. Bailey's wife paid a bond to bail him out of jail. The district attorney subsequently dropped the charges and did not prosecute Bailey.

Bailey sued, claiming his speech was constitutionally protected and that the arrest therefore violated the First Amendment and the Fourth Amendment (because there was no probable cause to believe the speech was criminal). The Fifth Circuit agreed:

[T]he district court concluded sua sponte that Bailey's Facebook post was not constitutionally protected speech under the First Amendment because it created a "clear and present danger," equating "Bailey's post publishing misinformation during the very early stages of the COVID-19 pandemic and time of national crisis" as "remarkably similar in nature to falsely shouting fire in a crowded theatre" and citing to Schenck v. United States (1919). Relatedly, the district court held that "Bailey's Facebook post may very well have been intended to incite lawless action, and in any event, certainly had a substantial likelihood of inciting fear, lawlessness, and violence," citing Abrams v. United States (1919). This was error….

[I]n concluding that Bailey's post was unprotected speech, the district court applied the wrong legal standard. While Schenck and Abrams have never been formally overruled by the Supreme Court, the "clear and present danger" test applied in those cases was subsequently limited by the "incitement" test announced in Brandenburg. As the Fourth Circuit has explained, the "clear and present danger" test from Schenck and Abrams, "[d]evoid of any such limiting criteria as directedness, likelihood, or imminence … applied to a wide range of advocacy that now finds refuge under Brandenburg," such that "Brandenburg has thus been widely understood … as having significantly (if tacitly) narrowed the category of incitement."

In Brandenburg, the Court held that "advocacy [that] is directed to inciting or producing imminent lawless action and is likely to incite or produce such action" is not protected by the First Amendment…. A comparison with Supreme Court precedent makes clear that Bailey's post was not "advocacy … directed to inciting or producing imminent lawless action" nor "likely to incite such action." …

The post did not direct any person or group to take any unlawful action immediately or in the near future, nobody took any such actions because of the post, and no such actions were likely to result because the post was clearly intended to be a joke. Nor did Bailey have the requisite intent to incite; at worst, his post was a joke in poor taste, but it cannot be read as intentionally directed to incitement….

Despite Bailey's arrest for "terrorizing," his Facebook post was also not a "true threat" unprotected by the First Amendment…. On its face, Bailey's post is not a threat. But to the extent it could possibly be considered a "threat" directed to either the public—that RPSO deputies would shoot them if they were "infected"—or to RPSO deputies— that the "infected" would shoot back—it was not a "true threat" based on context because it lacked believability and was not serious, as evidenced clearly by calls for rescue by Brad Pitt….

In United States v. Perez (5th Cir. 2022), we held that Facebook posts made in April 2020 in which the speaker falsely claimed that he had paid a person infected with COVID-19 to lick everything in two specific grocery stores in San Antonio was a true threat…. Bailey's absurd post is entirely different from the believable threat in Perez, which, unlike Bailey's post, threatened specific harm at specific locations and triggered complaints from the public to law enforcement.

The Court also held that the law was so clear that defendants should be denied qualified immunity for the arrest. That was so as to the First Amendment, largely for the reasons above. And it was so for the Fourth Amendment:

According to Louisiana courts, the crime of terrorizing requires (1) "false information intentionally communicated" and (2) "an immediacy element concerning the false information or threat that causes sustained fear or serious public disruption." The statute also requires (3) "specific intent … i.e., the intent to cause members of the general public to be in sustained fear for their safety, or to cause evacuation of a public building, a public structure, or a facility of transportation, or to cause other serious disruption to the general public."

The relevant facts and circumstances known to Iles at the time of the arrest were: (1) his supervisors asked him to investigate the post; (2) the content of the post itself; (3) Bailey was the author; (4) the comments below the post; (5) Bailey's statement to Iles that he meant the post as a joke and had no ill will toward RPSO; (6) nobody reported the post to law enforcement; and (7) the general social conditions during the early onset of the COVID-19 pandemic.

These facts and circumstances are not sufficient for a reasonable person to believe that Bailey had violated the Louisiana terrorizing statute. The statute's requirement that the communication have "an immediacy element concerning the false information" is lacking. Moreover, "causation of 'sustained fear' is clearly an essential element of this part of the statute." Here, however, there were no facts that would lead a reasonable person to believe that Bailey's post caused sustained fear. No members of the public expressed any type of concern. Even if the post were taken seriously, it is too general and contingent to be a specific threat that harm is "imminent or in progress." Nor would a reasonable person believe, based on these facts, that Bailey acted with the requisite "specific intent" to cause sustained fear or serious public disruption….

[T]he district court stated that the timing of the post during the first month of the COVID-19 pandemic—a time of dramatic change, fear, uncertainty, and misinformation—was "central" and "critical" to its probable cause analysis. While the social context of COVID-19 is certainly a relevant consideration, the general fear and uncertainty around COVID-19 does not turn Bailey's otherwise-inane Facebook post into a terroristic threat under Louisiana law….

Having determined that there was no actual probable cause for the arrest, we hold that Iles is not entitled to qualified immunity because he was "objectively unreasonable" in believing otherwise….

Instead, Iles relies on a recent unpublished decision, Stokes v. Matranga (5th Cir. 2022). In Stokes, this court granted qualified immunity to an officer who arrested a student for violating Louisiana's terrorizing statute when he posed for a photograph beside a drawing labeled "Future School Shooter" that was published on social media. Though Iles argues that this case is instructive because likewise in Stokes, the officer was aware that the social media post was done in jest, we find it distinguishable in at least one important way. In identifying the officer's knowledge at the time of the arrest, we stressed that he was aware that parents had contacted the school to express concerns and ask about taking their kids out of school. No such thing happened in this case. This, combined with Iles' knowledge that the post was a joke, severely undercuts probable cause for an arrest. As noted by the dissent in Stokes, "[o]fficers may not disregard facts tending to dissipate probable cause," and "[n]o decision by any court contradicts [this principle]."

Bailey is represented by Benjamin Field and Caroline Grace Brothers of the Institute for Justice, and by Garret S. DeReus. My students Samantha Frazier, Jonathan Kaiman, and Katelyn Taira and I filed an amicus brief supporting Bailey, on behalf of Profs. Profs. Rodney Smolla and Clay Calvert and myself.

Show Comments (20)