The Volokh Conspiracy

Mostly law professors | Sometimes contrarian | Often libertarian | Always independent

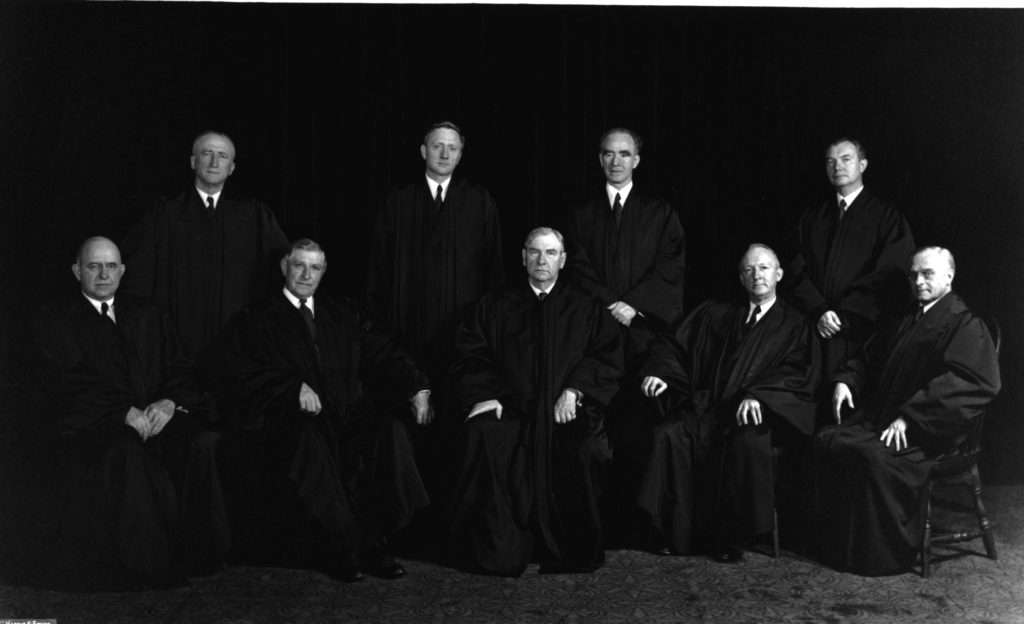

Today in Supreme Court History: August 1, 1942

8/1/1942: Military commissions conclude for eight nazi saboteurs. The Supreme Court upheld the constitutionality of these trials in Ex Parte Quirin.

Editor's Note: We invite comments and request that they be civil and on-topic. We do not moderate or assume any responsibility for comments, which are owned by the readers who post them. Comments do not represent the views of Reason.com or Reason Foundation. We reserve the right to delete any comment for any reason at any time. Comments may only be edited within 5 minutes of posting. Report abuses.

Please to post comments

American Mfrs. Mut. Ins. Co. v. American Broadcasting-Paramount Theatres, Inc., 87 S.Ct. 1 (decided August 1, 1966): Harlan stays state court judgment, affirmed by New York’s highest court, due to argument that contract at issue violated antitrust laws, even though no showing of prejudice from having to pay the judgment and irrelevant that petitioner had not sought cert even though “substantial federal question” (in fact cert was later denied, 385 U.S. 931, 1966, and stay automatically terminated) (at issue was whether agreement to sponsor network news program involved illegal “tying” prohibited by Sherman Act)

Holtzman v. Schlesinger, 414 U.S. 1304 (decided August 1, 1973): Marshall denies stay, which has the effect of allowing continued military operations in Cambodia; suit had been brought by Congresswoman Elizabeth Holtzman on basis of Congressional prohibition of such operations; Marshall’s opinion instructively reviews standards for granting a stay and how they might apply to this “sui generis” situation; he decides that the question should be decided by the full Court.

Note: three days later another application was made, to Douglas, who stayed Cambodia operations; later that day Marshall un-did the stay again, with all the other Justices agreeing with him except Douglas; the Second Circuit heard the full appeal and dismissed suit on August 8 on grounds that issue was political and therefore non-justiciable; cert denied in April 1974

Douglas was always a nutcase, but he was never more of a nutcase than he was in Schlesinger. Just how did he expect his order to be enforced?

How does the Supreme Court expect anything to be enforced if Congress and the executive branch ignore them? It's still valuable to make a correct ruling, if only for their place in history, and it might give some within the other branches greater authority in advocating that correct decision. At the least, it might prompt a resignation or too, and sway public opinion to change the other branches at the next election.

It seems unlikely that Nixon would have resigned or been impeached any sooner had Douglas persuaded the rest of the court, but you never know.

Actually, the courts have a whole bunch of tools of enforcement. For instance, if people disobey an unconstitutional law the courts can refuse to hear their prosecutions or impose sentences. If people fail to pay a judgment the court can attach property or funds. If the government fails to obey an injunction courts can enter orders the protect and enforce the injunction.

But the Court can do none of those things if the Court orders a military attack to stop. And if anything, the effect on the Nixon impeachment might have been the opposite- having established the right to disobey Douglas on the bombing, Nixon might have been able to disobey the tapes order too.

The mechanisms for enforcement in all cases depend on the proper operation of some other part of government, unless you intend for Supreme Court Justices to deal out justice with their own two fists*. A lot of actions to oppose illegal war, with less effect and greater risk, have been taken, and I would not join you in calling the people who did them nutcases for having done so.

* e.g., https://www.gocomics.com/tomthedancingbug/2015/07/10

The issue isn't the mechanisms involving other branches of government- it's that the military doesn't have to listen to the courts at all.

The best example of this is in the Civil War when Lincoln ignored Taney's habeas writs. Taney was exposed as impotent as a 100 year old man in a strip club.

Would he have been any more powerful if he had issued nothing? Saving your powder makes sense, but never using it means you never had any power.

Inter arma enim silent leges

“In times of war, law falls silent.”

Why would you say that (I'm assuming in response to the Ex Parte Quirin case)?

Decisions were made, defendants maintained their rights throughout the process, and even had a chance to be heard in our highest court.

By that logic, why not try all crimes in front of a military commission?

y = mx + b

Wow!

Your "m" got real slippery.

You said that the "defendants maintained their rights throughout the process". I would think that's not right, since they didn't get a jury or an independent trial court. I'm not sure how that's a slippery slope argument.

The question is what rights did they have? The same as a civilian criminal? As a uniformed POW? More rights? Fewer?

Before you can ask whether their rights were respected you first have to determine what rights they were entitled to. Under civilian law and the Geneva Conventions the answer is, not many.

The Geneva Conventions didn't exist during World War II.

But anyway, there was no war in the United States, so the correct answer was to try these people like common criminals, as the 5th and 14th amendment require. The Supreme Court held otherwise because that was the politically cowardly thing to do. But that was wrong, just like Korematsu was wrong and just like the majority in Liversidge v. Anderson was wrong.

To quote Lord Atkin (in dissent):

today’s movie review: Around the World in 80 Days, 1956

Among Best Picture winners this is often called 1) one of the worst, and 2) one of the most fun to watch. This is a comedy (unlike the Jules Verne book it was based on, which is more like a travelog) with David Niven as a fussy English rich man, Phileas Fogg, who bets his card playing buddies in the Reform Club in 1872 (I think) that one can make it around the world in 80 days. He is accompanied by his servant Passepartout and obviously spends gobs of money as we follow them along on balloons, trains, boats. Unfortunately the day he leaves, there’s a major bank robbery in London and he is pursued by a detective who is convinced he’s financing the trip with the stolen loot. At the end, about to return to the Reform Club on the 80th day, he’s put in jail, and sprung the next day, in a state of dejection until Passepartout sees the morning paper and realizes that because they were traveling east, they’re actually a day ahead.

The movie is composed of a lot of funny bits that you can’t help but laugh at despite their corniness, and lots and lots of cameos. It reflects an earlier age of moviegoing, when there was an intermission, and people stayed to watch the credits. The justly famous cartoon end credit sequence recaps the movie and identifies all the cameos (stars who are largely unknown to us now). My favorite is at the end when Verne appears in the clouds and throws his book down at the director, Michael Anderson.

Passepartout is played by Cantinflas, a Mexican comedian who made lots of movies. My wife watches Spanish TV where his movies run every Saturday afternoon. His best work was wordless; he was a combination of Charlie Chaplin and Harpo Marx.

Best line, delivered perfectly: Niven, idly fingering dust (which he hates) off his long-disused dining room table, believing he’s lost the bet: “At the moment things do not appear to be particularly promising.” The movie both makes fun of Niven’s British stiff upper lip while at the same time respecting it.

A lot of “whitecasting” which would be unacceptable nowadays, but Shirley MacLaine is very good as a shy Indian princess (saved by Fogg from a suttee) and Peter Lorre as a samurai. The British Empire is painted as faintly ridiculous (e.g., the huge-mustachioed Cedric Hardwicke as a self-important jungle guide). At the end, when Fogg brings the princess into the Reform Club — a woman at the Reform Club! (and, unmentioned, a nonwhite one at that) — Fogg, whose mind has been opened by the journey, says the downfall of their males-only rule might mean “the end of the British Empire”. At this shocking thought the place falls apart in a slapstick end sequence.

Not “Best Picture” material, like Amadeus was, but fun.

Great review and not one mention of anything Trump related.

There was a 2014 movie “Cantinflas” that gives you an idea why he was a big enough deal to get into “Around the World in Eighty Days” in the first place. Not great, but it has its moments and the best scene (a routine he did to “Bolero”) is over the closing credits. I'd like to see his pantomime work.

I've found a couple on Netflix so I'll get my wish.

The British Empire died on July 26, 1956 when Nasser seized the Suex Canal -- and got away with it.

Eisenhower refused to get involved and neither England nor France could do anything about it, the war had bankrupted them, and the rest is history. And in 1954, when the line was written, the cracks were probably viable.

"Eisenhower refused to get involved . . . . "

Yeah, no.

The US was heavily involved - diplomatically - but not militarily.

This is, of course, not remotely what happened. England and France (and Israel) could and did do something about it, seizing the Suez Canal by force. Eisenhower did not "refuse to get involved." Rather, he got very involved — by siding with Egypt against Britain and France. It was that — showing that Britain had no ability to act if the U.S. opposed it — that signified that Britain was no longer anything resembling a world empire.

It would be better if the Academy recognized more comedies. A couple of them won Oscars in the 1960's.

There is a general feeling amongst “them” that comedies somehow don’t deserve full recognition as great works of art the way that serious works do. If in a list of the greatest operas, I mention Don Giovanni, Magic Flute, Don Carlo, The Ring, Boris Godunov, etc. other opera lovers and critics (the overlap is not perfect) would nod their heads even if they might not agree 100% (“Wot, no Bellini, Puccini. R Strauss?” etc etc). But if I said, as I truly believe to be the case, that the greatest opera ever written is The Barber of Seville, more than a few would be shocked and would dispute it as loudly as Birgit Nilsson, as Brunnhilde, riding Grane into the flames.

How about 563 miles in a day or so?

Don't forget to buy a squirrel. And enjoy that Barbie Museum!

Quirin was decided on July 31, 1942.

It seems really, really odd, in a segment that is supposed to be on Supreme Court anniversaries, to always be giving anniversaries of things that only have some small connection to the Supreme Court. Even here, the date of an actual important Supreme Court decision could have easily been given, the opportunity was bypassed yesterday, and instead, the date connected with lower tribunal proceedings is given.

It appears the tribunal waited for the Supreme Court’s judgment, which was announced the previous day, July 31, 1942, before finally concluding.

Blackman's choices are often bad. Ignoring a more significant case is probably the worst of it, whether for an obscure appointment, birthday, retirement or death, but playing Quirin out over successive days is also egregious. But I think I'd rather have a tenuous SCOTUS connection to something more significant than hearing about an episode of Supreme Court Building maintenance.

Conservatives seem drawn to random capitalization; refraining from capitalizing Nazi in this context seems especially odd, though.

Are you feeling disrespected?

I'm feeling victorious in the culture war.

The Volokh Conspirators and their right-wing fans wouldn't understand.

Bud Light lost billions for hiring a typical Democrat spokesperson. 100s of Bud Light Democrats are getting laid off.

lol

Don't be such a Democrat

But to a wrong result. Whether the President did or did not overstep the law is not a “political question”; it is the kind of “controversy” (and separation of powers issue) the Court was set up to address.

"kind of “controversy” (and separation of powers issue) the Court was set up to address"

National security is not a "judicial power".

Whether the President did or did not overstep the law is not a “political question”; it is the kind of “controversy” (and separation of powers issue) the Court was set up to address.

Stopping a bombing is absolutely a political question (one textually assigned to other branches of government that SCOTUS has absolutely no power over) and the Court has absolutely no business deciding such a thing. I can't think of a subject area where the Justices would be more ignorant.

No, but making a determination of whether the President is doing thing X that Congress forbade is.

In an undeclared war? What a can of worms.

Congress has the power of the purse, and people opposed to bombing in Cambodia can retroactively flip flop on what would later br called the MQD and suddenly find it's a useful and important principle.

Congress has the power to make rules and regulations for the military. There was a rule they not bomb Cambodia. Seems like something a judiciary could decide had been broken or not.

And then they rule it and Nixon says "I don't care, they had no power to rule this", and continues bombing. And at that point, the Supreme Court looks like a bunch of fools.

People are addicted to this notion that the Rule of Law is everything. Well, the Rule of Law is important. But there are some things where courts have zero legitimacy, zero power, and zero expertise to decide. And in those situations, if the President wants to violate the law, that's why we have an impeachment provision. (And indeed some members of Congress tried to impeach him over the bombing of Cambodia, which was fully within their power.)

You can't have an unelected life tenured Supreme Court making decisions about military targeting. Indeed, the argument that they should is absolutely crazy, which is why Thurgood Marshall- no fan of Nixon and no fetishist of executive power- properly put a stop to this unrealistic enterprise.

If Congress makes a law that says that the army can't drop any bombs on Cambodia, I don't see why the courts can't check whether the army complied with that law or not.

So what you guys want is a meaningless declaratory judgment by a court with no power saying "uh uh uh, what a naughty boy you are, Mr. President". And what will that accomplish other than Nixon saying "this is an illegal judgment and you jerks have no power to stop me"?

No, if you don't have the power over the subject area (which, again, is textually committed to the other two branches of government), you don't have the power to say it is illegal either. The Supreme Court's opinion of the bombing of Cambodia is irrelevant, and Marshall was right that they should keep it to themselves.

It's not a major question. The Constitution literally gives the power over military targeting to the President (commander in chief) and the power to make rules over the armed forces to Congress. There's no judicial power here whatsoever and you don't need a made up doctrine to get there.

I guess there's a segment of the Left that sees the whole political question doctrine as made up (possibly because of its role in gerrymandering and redistricting cases?) but it's not. Certain things are not part of the judicial power, and deciding who the military targets is one of them.

Lots of comedy in it, but more a serious movie than not.

Replying to Queen:

Just what we need; 535 generals weighing in.

There is a rules and regulations grant, which is enforceable through impeachment or cutting off funds (both of which were pursued in the 1970's).

What there isn't is judicial power. Literally no country in history with an independent judiciary lets judges conduct war.

Your idea has no stopping point. Congress passes a law. The President oversteps it. The Court weighs in and voids whatever thing he's doing, whatever executive order he's issued. Doesn't that happen all the time? And here, wasn't Congress exercising its war power and the President overstepped it?

My interpretation has a definite stopping point, which is questions that are textually committed to the other branches where there is no judicial power.

Again no country in history with an independent judiciary has ever said judges can conduct a war. This is not a thing and if you guys can't understand why even Thurgood Freaking Marshall got this I don't know what to tell you.

Why did Nixon obey the Court in 1974? Why didn’t he just hold onto the tapes?

Your position is that the power of Congress to declare war is meaningless — because the President can just wage it (or not) whenever he wants.

The point of President being the Commander-in-Chief is to prevent a split of lines of military authority -- when war is fought.

Right. A movie like Airplane!, one of the best of all time, doesn't even get taken seriously as an Oscar contender. Same with Blazing Saddles.

Here's a way of getting at it. There are at least 2 colorable arguments that the Kosovo operation was illegal. Suppose Rehnquist had issued an injunction against it. What do you think Bill Clinton would have done?

It seems to me the only plausible answer is "ignore it" and why shouldn't he? Why should he ever listen to Rehnquist?

"This is not a thing and if you guys can’t understand why even Thurgood Freaking Marshall got this I don’t know what to tell you."

Well said.

I think President Clinton would have obeyed the Court. And I think that if he hadn't, he should have been impeached. And I think that the Supreme Court should apply the law regardless of what it thinks may or may not happen subsequently.

The political question doctrine IS the law, Martinned. And it's the law because only an idiot would found a country that gave unelected independent judges the power to dictate military tactics and decide how a war will be fought. Thankfully, at least in this respect, our country was not founded by idiots.

The purpose of the President being Commander in Chief of the armed forces was to prevent a split of military authority — when a war is being fought.

The Framers called the upper house the “Senate”, appropriating the Roman term, and maybe they were conscious of what happened in the late Republic, where Senators had their own armies and there was civil war.

Nixon obeyed the Court in 1974 because the Court had enormous power over a criminal case that charged Nixon with serious crimes, and could have imposed sanctions on Nixon that would have resulted in his imprisonment after leaving office had he refused.

And the one branch of government that DOESN'T have "military authority" in a war is the judiciary.

I'll see that and raise you Dr. Strangelove, which lost to My Fair Lady. To be fair, at least Dr. S got nominated, unlike The Producers.

You think that the courts should take into account whether the President will obey their rulings or not? The same President that has a constitutional duty to see that the laws be faithfully executed, and who can be impeached if he refuses to do that?

Well stated.

Let alone a single Justice! Not even as a temporary measure.

I absolutely think the Supreme Court should not do things that establish the principle that the political branches should ignore its rulings, or to establish the principle that it enters orders on stuff it knows nothing about and has no authority over.

The Supreme Court isn't a tribunal of platonic guardians. It's a group of 9 people we have granted a lot of power to on the condition that they not get out in front of their skis. That's how the law actually works- the political question doctrine is just as much "law" as any supposed constitutional restriction on Nixon bombing Cambodia. Disobeying the law on political questions so that you can make a meaningless ruling that Nixon has no obligation to obey would be a terrible thing for SCOTUS to do, and again, Thurgood Marshall is no conservative and no lover of executive power and he got this.

Airplane! is funnier than Dr. Strangelove.

Strangelove was too scary to be funny.

That too.