The Volokh Conspiracy

Mostly law professors | Sometimes contrarian | Often libertarian | Always independent

Today in Supreme Court History: July 21, 1824

Editor's Note: We invite comments and request that they be civil and on-topic. We do not moderate or assume any responsibility for comments, which are owned by the readers who post them. Comments do not represent the views of Reason.com or Reason Foundation. We reserve the right to delete any comment for any reason at any time. Comments may only be edited within 5 minutes of posting. Report abuses.

Please to post comments

NCAA v. Board of Regents of University of Oklahoma, 463 U.S. 1311 (decided July 21, 1983): White (a former NCAA star himself) stays decision against NCAA because certiorari would probably be granted (lower courts had held that arrangement banning televising of teams not selected by networks was illegal price-fixing under antitrust laws); cert was granted but White got pushed back into his own end zone (i.e., the Court affirmed)

Delo v. Blair, 509 U.S. 823 (decided July 21, 1993): stay of execution denied by full Court because facts similar to recently-decided Herrera v. Collins decision (conviction upheld due to uncoerced written confession despite numerous post-trial witness affidavits); Blackmun, Stevens and Souter dissented, as they had in Herrera, basically on the argument that Herrera was wrongly decided

South Park Independent School District v. United States, 453 U.S. 1301 (decided July 21, 1981): Powell turned down stay of desegregation order because facts are similar to recent case where cert was denied, even though he personally would vote to grant cert and had voted to grant cert in the prior case

today’s movie review: Twelve Angry Men, 1957

This movie is justly praised as the greatest jury movie ever made (though that is a small genre). I don’t have to remind you of the great performances by great actors who I won’t name here.

Some extra notes.

The only noticeable flaw in the plot is Juror #8 going to the crime scene neighborhood and buying another of the supposedly unique knife that was used in the murder. A juror is not supposed to do his own investigation. At a later point he dramatically jabs it into the table next to the exhibit knife. Why didn’t he do this at the beginning, when he expressed only vague doubts?

This incident does illustrate (perhaps overly broadly) something I’ve noticed in listening to jurors after a verdict, that each juror brings his own experience to bear on the evidence. It’s the short man (Juror #2) who wonders how the defendant could have stabbed his much taller father with a downward thrust of the knife. It’s the product of gang culture (Juror #5) who notes that a switchblade is always jabbed upwards, not downwards. It’s the painter (Juror #6) who has worked next to an el who notes that the trains are so loud when they pass by (I can testify to this also!) that the boy’s supposed shout could not have been heard. Finally it’s the old man who has never worn glasses (and probably has seen his friends have to put on glasses over the years) (Juror #9) who notices the dent marks on the witness’s nose.

Also notable is the staging. As the film proceeds and tension mounts, the camera lowers and closes in, and finally is looking up at full-screen faces. This was a problem during production because film sets never have ceilings, but one had to be visible toward the end.

Juror #1 is not a very good foreman. Eventually it’s Juror #4 and Juror #8 who control the proceedings. They are on opposite sides but seem to respect each other.

We are made to assume that the bigot (Juror #10), being rejected by everyone else, is having some kind of epiphany while sitting at that desk in the corner, and finally votes not guilty. I’m not sure I can buy that.

It’s been argued that, even if each piece of evidence is called into doubt, the combination of all those almost certain events makes the boy guilty beyond a reasonable doubt. A scientist would not accept this. He would call a guilty verdict a “conjecture” — something that seems to be true but has not been proven. I don’t if anyone here has been the victim of a number of circumstantial (but not true) appearances, but I have.

In high school English class I saw a neglected paperback on the windowsill, “Twelve Television Plays”, which included this one. The “Dramatis Personae” description of Juror #9 was “an old man, defeated by life”. The film, in the brief ending tag, where he shakes hands with Juror #8 and they exchange names, shows that his faith in humanity has been restored. In the background one can see Lee J. Cobb trudging down the courthouse steps. (The earlier TV version play was on TV before it was on film, and is inferior to the film because it is less subtle. For example, two of the jurors actually get into a fistfight.)

The beginning and ending exterior shots are of 60 Centre Street, the New York county trial (“Supreme”) court, where I’ve spent a good part of my career. My best experiences were not in courtrooms but in the Motion Support Office (Room 119). Those guys knew everything, and were courteous and helpful. A world of perversity existed in the Ex Parte Office (Room 315), where after you submitted your Order to Show Cause (a motion for something to be done quick) they sat on your papers, doing nothing with them, and you personally had to come back the next day and submit it to the assigned judge’s clerk for signature.

The common sense point that Juror #9 makes at the beginning when he’s the first to side with Juror #8 — that it’s not easy for one person to stand alone — was ignored by the Supreme Court in Williams v. Florida, 1970, where it said a six-person jury was o.k. instead of twelve. In a six person jury it is more likely that there will be one person against the others; in a twelve person jury it’s equally probable that there would be two, and each would support the other.

Juror #11, the watchmaker from an unspecified (probably Eastern European) country, gives a little speech about how he is impressed by the American jury system. He is as appreciative of our trial by jury as Juror #7 is apathetic about it. By now I know a lot of people who are from other countries (mostly from what we used to call the Third World), and they would applaud what Juror #11 has to say. They are glad to be here and have the rights we enjoy here.

Finally, I’m most impressed by Juror #4, his calm objectivity. When he’s just one of 3 in favor, he states his case, beginning by admitting to Juror #8, “you’ve made some excellent points”. And when the old man points out the dents in the witness’s nose, the camera focuses on his face for a long time. He knows exactly what that means and it means game over for the pro-guilty argument. But he’s not disappointed. He calmly says, “I have a reasonable doubt now”, and switches his vote.

My problem with 12 Angry Men, and perhaps it's from practicing criminal law on both sides, is, frankly, the Kid is obviously guilty, or at least is certainly proved to be beyond a reasonable doubt.

Here is all the evidence you must discount to believe he is innocent:

1. The Kid loudly tells his father, "I'm going to kill you!" A few hours later, his father is killed.

2. The old man down the hall saw the Kid flee the father's apartment after he heard the father scream.

3. The old lady across the street saw the Kid stab his father through the window.

4. The Kid's alibi is that he was at the movies, but, no more than a few hours later, when questioned, he can't remember any of the titles or any details whatsoever about the movies he saw.

5. The murder weapon (the switchblade), by the Kid's own admission, is identical to one he owns, but, in an incredible coincidence, he claims he lost it THAT VERY DAY.

The jury engages in illogical absurdity. In isolation, sure, any one of those could be explained away, but ALL of them? For example, it is suggested that the old man who testifies he saw the Kid flee the apartment is either hallucinating or lying. Pretty weak. The cumulative nature of the evidence certainly adds up to guilt beyond a reasonable doubt to me.

Compare and contrast to "My Cousin Vinny" as to what counts as reasonable doubt.

Number 5 is the only one that's particularly meaningful. The whole point is that the old man down the call couldn't see the kid flee the father's apartment, and therefore didn't. Ditto for the old lady across the street. The "I'm going to kill you" is a joke as evidence. I'll give some minor points for the movie issue, but I don't think it's like going to Mission Impossible or the latest MCU offering and then forgetting; I think you're projecting modern sensibilities here.

People went to the movies a lot more often then, and saw double features. Also, as is pointed out in the film, if the kid was innocent it meant he was in grief and shock seeing his father stabbed to death on the floor, with scary police all around pressing him for answers. He probably could barely remember his own name.

I remember a movie review long ago that stated you would probably enjoy the movie but also forget that you ever saw it later that day; tellingly, I cannot remember what the movie reviewed was.

If the kid was like I was at his age, he would have been too busy kissing (etc.) the girl he went with and paying no attention to the movie whatsoever. (And in my case it was sometimes a drive-in outside of town, and that being even more true.)

Hah, been there at least once, and I remember the name of that movie (Greedy).

David, the fact the old man may have worn glasses is meaningless unless you know WHY the old man wore them, and you don't.

Let me present three possibilities, all quite reasonable.

1: He is old and hence his lens isn't as flexible as it used to be, and thus needs reading glasses. Most adults over the age of 40-50 do, while their distance vision is still excellent.

I'm not going to go into optics here because you clearly aren't bright enough to understand focal lengths and the rest, but distances of less than 6-10 feet are far more sensitive to the correct mixture of lenses (your eye has three and glasses makes four) than is "down the hall." LOTS of old men can see "down the hall" fine, but can't read a label without their glasses.

Many have bifocals that they wear all the time -- or just the half lens for reading.

Second, old men often have cataract surgery, the replacement of a cloudy lens with a plastic one -- that has a fixed focal length and that is for distance vision. So they wear reading glasses -- sometimes just the half lens reading glasses.

Third, there are sometimes imperfections in the lens. Called astigtimism, they are optically corrected by glasses -- although the person would be able to identify a person "down the hallway" without them. The image might be a little wavy, but clearly identifiable.

You don't know what you are talking about -- without knowing WHY the man wore glasses, you DON'T know that he couldn't see down the hall without them!

And then people often adapt -- I know a woman who got her drivers license and had a perfect driving record for 4 years without ever knowing that she had 20/200 vision (the E on the top of the chart). She could recognize me and everyone else at a distance without her glasses...

The prosecution should have shown 1) either that the witness didn’t wear glasses at all or 2) why not wearing them was irrelevant in that situation. As Juror #8 pointed out, the jury shouldn’t have to guess about that.

This hole was plugged in “My Cousin Vinney” when the Austin Pendleton character (poor guy) noted the glasses in the witness’s pocket and the witness answered that they were only for reading.

Blah blah blah. I'm glad you think your job as a janitor who thinks he can teach high school social studies makes you an expert on optics, but this is all irrelevant blather from someone who hasn't seen the movie, because the reason the old man couldn't see him down the hall was not lack of glasses, but because he couldn't get to the hallway in time because of his physical disability.

Oh, and as someone who has worn glasses for the last 47 years or so, and progressive lenses for at least the last ten, your explanation was utterly unhelpful anyway.

So says everyman.

"an old man, defeated by life"

Dr. Ed? Mr. Bumble?

Eh, that's just mean. Facts, let alone life, don't seem to defeat most commenters here, and especially not Dr. Ed 2. And I see little evidence that Bumble is old, anyway.

It’s been argued that, even if each piece of evidence is called into doubt, the combination of all those almost certain events makes the boy guilty beyond a reasonable doubt. A scientist would not accept this. He would call a guilty verdict a “conjecture” — something that seems to be true but has not been proven. I don’t if anyone here has been the victim of a number of circumstantial (but not true) appearances, but I have.

FWIW, this really is just an issue of what constitutes reasonable doubt.

Because it really is true that each coincidence reduces the likelihood of innocence. To see this, take the example of a surely guilty person, OJ Simpson. For OJ to be innocent, among any number of coincidences, all of these things had to happen:

1. The murderer had to own a pair of relatively expensive gloves exactly like the extremely rare, not available in Los Angeles gloves that OJ’s ex-wife purchased 2 pairs of and OJ was seen wearing at football games.

2. The murderer had to wear size 12 Bruno Magli Lorenzo shoes, rich man’s shoes that were in OJ’s shoe size.

3. The murderer had to have committed the murders at the exact time when OJ had no alibi.

4. Mark Fuhrman had to have picked up the second glove from the scene after numerous cops had inspected the scene and not seen a second glove, and he had to have done this not knowing either:

a. That he would be asked to go to OJ’s house and would have an opportunity and a moment of total seclusion to drop it there; and b. That OJ had no alibi, that there were no witnesses or recordings of the murders, and that nobody had come in and confessed to the murders at a police station.

5. The murderer had to have driven a 1992-1993 Ford Bronco that deposited carpet fibers onto the murder scene, just like OJ owned.

6. The murderer had to have committed the murder on a night when OJ had a bloodstain in his car (the defense theory was that bloodstain was already there, because it had been photographed, and Ron and Nicole’s blood was later planted on top of it).

7. The murderer had to have committed the murder on a night when OJ had multiple knife lacerations on his hand, the same hand that matched the glove that DID fall at the scene (strongly suggesting OJ lost the glove in his fight with Ron and then cut himself).

Etc.

The point is, each of those coincidences ABSOLUTELY decreases the probability of innocence, and when taken together they decrease the probability of innocence to an extreme degree.

And then the question is when is doubt no longer reasonable?

I see your point.

(Though the evidence in the O.J. case was a lot stronger.)

I was thinking via multiplication, where if you take five things that are each 90% possible, you end up with (0.9)^5 = 59% possible. But it should be via addition, where you're working at each step with what is left over from the last step. .9 + (.9 * .1 = .09) + (.9 * .01 = .009) + (.9 * .001 = .0009) + (.9 * .0001 = .00009) = .99999, i.e. 99.999% possible.

If any one piece of evidence was a 90% indicator of guilt, then yes. Take the complement of the inculpatory evidence prob – here, 10% – and multiply those together and subtract from 1.

So 10%^5 = 0.001%. 1- 0.001% = 99.999%

But if all of them needed to be in place for guilt, then you do indeed multiply: 90%^5.

And note the – here we go again, Frank D! – Bayesian reasoning approach that apparently Dershowitz didn’t get. When it turned out that OJ had beaten his wife, Dershowitz tried to argue that as only (e.g.) 1 in 1,000 men who beats their wives murders them, so it shows low probability. One of the defence team then pointed out that if, say, 1 in 100,000 men who do not beat their wives murders them, knowing that a man beats his wife makes it a thousand times more likely than he murdered her.

Also, if you look at the percentage of wives, ex-wives, girlfriends, and ex-girlfriends who are both (1) physically abused and (2) later turn up murdered, the percentage of cases where the culprit turns out to be the abuser is very, very high.

Yup - it's not "what percentage of abusive men murder their partners", but "what percentage of murdered partners had been abused by their men?"

It's "what percentage of the time is the abuser guilty of murder when the battered spouse turns up dead?".

The thing with the glove was "if it doesn't fit, you must acquit."

Would it have been permissible for the State to obtain another pair of the same gloves, demonstrate that OJ could wear them, and then soak them in blood overnight, let them dry, and then show that OJ now couldn't wear them?

I understood exactly what happened -- they got wet and shrank, fine leather will do that. Cheap leather as well, but I digress.

I'm also surprised that OJ was only a size 12 -- I'm size 13 and as a pro athlete, you'd think he'd have developed the muscles in his feet.

As I recall when OJ tried them on in court he already had on latex gloves. Nobody's gloves go on smoothly if you already have latex gloves on. Try it yourself.

(Why protect the gloves with latex? What were they saving them for?)

The prosecutors brought in a fresh pair of size XL Aris Isotoner gloves the next day. They fit OJ's hands perfectly.

Chris Darden screwed up. But in the hands of a jury that wasn't nullifying, that would have never mattered.

A juror is not supposed to do his own investigation

Wasn't there a recent 5th Circuit case where the Court said that the jury could have done their own investigation on the effectiveness of using a knife as a screwdriver?

Isn't that common knowledge? I've often used a butterknife as one.

Common knowledge, like common sense is hardly common.

South Park Independent School District v. United States

Paging Eric Cartman, Paging Eric Cartman...

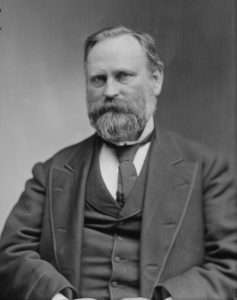

Stanley Matthews was first nominated to the Supreme Court by President Rutherford B. Hayes on January 25, 1881, 37 days before the end of Hayes’ presidency. The Senate Judiciary Committee took no action on the nomination.

On May 14, 1881, Hayes’ successor, and fellow Republican, James A. Garfield, re-nominated Matthews. His nomination was reported out of the Judiciary Committee with a negative recommendation. Despite, this, the Senate confirmed Matthews by a vote of 24-23, the only justice to date confirmed by a single vote.

The vote breakdown in the Senate was interesting for the Republican president’s Republican nominee. Democrats voted 14-9 in favor of confirmation, while Republicans voted 10-13. Independent David Davis, former Supreme Court justice and Lincoln campaign manager, voted "nay".

What had Matthews done to irritate his fellow Republicans? Well, a few things, but, chiefly, in 1859, as the U.S. Attorney for the Southern District of Ohio, Matthews, though an avowed abolitionist, had prosecuted a newspaperman under the Fugitive Slave Act for harboring runaway slaves. In 1861, Matthews resigned as U.S. Attorney and was commissioned a lieutenant colonel in the Union Army. In 1862, President Lincoln nominated him for a promotion to brigadier general, but the Senate took no action on the nomination. Nineteen years later, it seems, all was not forgotten and forgiven.

Matthews died at the age of 64, having served just shy of eight years on the Court. His most notable opinion is probably Yick Wo v. Hopkins (1886), in which a unanimous Court held that a facially neutral statute, administered in a racially biased manner, was invalid under the Equal Protection Clause.

Scalia's concurrence in Herrera is unconscionable and shows you how his judicial philosophy and "I'm smarter than everyone else and right when everyone else is wrong" ego could lead him to the darkest places.

If Justice Scalia had known anyone in his privileged, upper class life who might actually be falsely accused a murder, he would have never in a million years concluded that the Constitution is just fine with innocent people getting executed. And he was too stupid and too evil- I am sorry, those are the only two words to apply to this- to see that. He congratulated himself for being so principled. He's so principled that you see, he's willing to say it's legal for the state to murder innocent people! That's sticking to your principles. As long as someone else gets to be the victim, of course.

Yes - and the conservative justices' response would be, AEDPA, now fuck off and die.

Herrera was in all likelihood innocent, fwiw.

It was a 6-3 decision written by Rehnquist. Why the hair up your ass over Scalia's concurrence?

Also, the son of a college professor at Brooklyn College and an elementary school teacher hardly seems upper class.

Because Scalia wrote a bloodthirsty, immoral, evil, disgusting, smug, incredibly dumb-while-thinking-he-was-brilliant concurrence that, if it became law, would mean the state could literally murder an innocent person (whom Scalia could rest assured would never be himself or anyone he cared about).

Not inclined to get in a pissing contest with someone as angry as you. There is more going on then your hardon over Scalia's concurrence on this decision.

I'll say again that it was a 6-3 decision with Rehnquist as the one who wrote the opinion of the court and I don't see anything in Scalia's concurrence that fits with your description.

In any case, Scalia is dead and nothing in his concurrence "became law".

Still claiming his childhood was upper class?

If you can't see the problem, you are part of it.