The Volokh Conspiracy

Mostly law professors | Sometimes contrarian | Often libertarian | Always independent

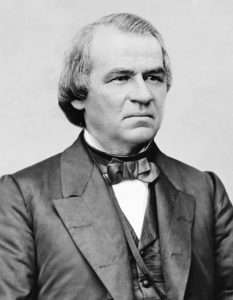

Today in Supreme Court History: May 26, 1868

5/26/1868: Senate acquitted President Andrew Johnson and adjourned as court of impeachment. Chief Justice Chase presided over that trial. Johnson is one of four presidents that did not appoint any Supreme Court Justices. The others are William Henry Harrison, Zachary Taylor, and Jimmy Carter.

Editor's Note: We invite comments and request that they be civil and on-topic. We do not moderate or assume any responsibility for comments, which are owned by the readers who post them. Comments do not represent the views of Reason.com or Reason Foundation. We reserve the right to delete any comment for any reason at any time. Comments may only be edited within 5 minutes of posting. Report abuses.

Please to post comments

United States v. Salerno, 481 U.S. 739 (decided May 26, 1987): upholding Constitutionality of Bail Reform Act of 1984 which requires denial of bail if after a hearing the court determines that release would be a danger to the community

Kellogg Brown & Root Services v. United States, 575 U.S. 650 (decided May 26, 2015): qui tam (“private attorney general”) action against contractors who allegedly falsely billed the government for logistical services in Iraq was time-barred; Wartime Suspension of Limitations Act applied only to criminal prosecutions, not civil actions

Camreta v. Greene, 563 U.S. 692 (decided May 26, 2011): refusing to entertain social worker’s petition to review holding as to Fourth Amendment violation when conducting a warrantless interview with child as to possible sexual abuse because even though the Court can sometimes entertain an appeal by a successful party (judgment had been in social worker’s favor due to qualified immunity) the case was moot; the child did not appeal her loss, had grown up and moved across the country

Montejo v. Louisiana, 556 U.S. 778 (decided May 26, 2009): statements made after defendant was appointed counsel admissible even though defendant not aware that counsel has been appointed because Miranda warnings were sufficient (overruling Michigan v. Jackson, 1986)

United States v. Classic, 313 U.S. 299 (decided May 26, 1941): Congress has power to criminalize misconduct in primary elections for Congress (thereby sustaining convictions of election commissioners who switched votes in favor of Hale Boggs) (I remember him — this election started his long career. He disappeared in a plane crash in Alaska just before winning re-election in 1972. His daughter, Cokie Roberts, became a Beltway talking head.)

Quill Corp. v. North Dakota, 504 U.S. 298 (decided May 26, 1992): Dormant Commerce Clause prohibits a State from collecting sales or use taxes from out-of-state companies selling to its residents (overruled by South Dakota v. Wayfair, Inc., 2018)

Commil USA v. Cisco Systems, Inc., 575 U.S. 632 (decided May 26, 2015): good-faith belief that there is no valid patent is not a defense to charge of infringement and inducing others to infringe (devices for accessing wireless networks were manufactured and sold by defendant)

United States v. Tinklenberg, 563 U.S. 647 (decided May 26, 2011): time spent on making and getting decision on Government’s pretrial motions does not count toward the 70-day deadline of the Speedy Trial Act of 1974 (18 U.S.C. §3161) even if it doesn’t actually delay trial

Haywood v. Drown, 556 U.S. 729 (decided May 26, 2009): a State cannot close its courts to plenary 42 U.S.C. §1983 lawsuits (striking down New York statute requiring any lawsuit against correctional officers to be brought in Court of Claims, where there is no jury trial, punitive damages, or injunctive relief)

Reagan v. Farmers’ Loan and Trust Co., 154 U.S. 362 (decided May 26, 1894): federal suit against State railroad commissioners for actions undertaken in their official duties (setting rates) was not in violation of Eleventh Amendment because suit was not actually against the state (Texas) but the commissioners and the State statute could be read to allow suit in federal court

"good-faith belief that there is no valid patent is not a defense to charge of infringement and inducing others to infringe"

I am surprised this was an open question in the 2015. A similar question came up at work in the 1990s when we had patents and the other company might not realize it was infringing them. Us non-IP professionals determined that innocent infringement (as it would be called in a copyright case) was a defense to triple damages but not to liability.

Thanks.

Maybe the question didn't come up so much in the predigital age. Nowadays we sit on our butts and assemble things at the keyboard, not realizing that some of the sub-programs or widgets might be patented.

“United States v. Salerno, 481 U.S. 739 (decided May 26, 1987): upholding Constitutionality of Bail Reform Act of 1984 which requires denial of bail if after a hearing the court determines that release would be a danger to the community”

For once, Brennan and Marshall got it right: They believed this Orwellian law from 1984 was unconstitutional, and they dissented.

All but two of the states admitted to the Union since 1789 guaranteed bail in noncapital cases, indicating that this was - what's the term? - a right retained by the people.

The statute seemed to violate separation of powers and was probably enacted in response to a man out on bail murdering someone (a la Willie Horton). It should be strictly up to the judge, under a court's traditional powers, to determine whether to set bail; there may be cases where the judge will let a defendant out on bail even if a danger to the community. It could be that the defendant will be too closely watched to do any harm, or it could be that he would be more dangerous in jail. It takes some imagination, but I think there would be such instances.

I can think of reasonable arguments against the Bail Reform Act. "It's unfair that a judge who thinks that there's clear and convincing evidence that a defendant will unreasonably endanger the public can't release them anyway" isn't one of them.

Setting bounds to the discretion of judges is a key function of the Constitution and of crminal legislation. What more powers can judges seize – the power to ignore sentencing restrictions?

Why?

Because without any attempt to find out which rights were retained by the people, the 9th Amendment is useless, and the Privileges and Immunities Clause of the 14th Amendment is deprived of much of its power.

And because if we’re trying to find what the retained rights of the people were, its useful evidence to find what the people put in their own state constitutions dating back to the Founding and afterward, with the consent of Congress in admitting these states to the Union.

And in this context, a right against excessive bail would be of much less value if it simply meant “reasonable bail if Congress, as a matter of grace, declares the offense bailable, otherwise no bail at all.”

And because leaving the right to bail up to the Justices’ idoisyncratic interpretation of an accordion-like substantive due process, then the right is not secure, as we’ve seen in practice.

"Federal judge James A. Parker eventually apologized to [Wen Ho] Lee for denying him bail and putting him in solitary confinement. He excoriated the government for misconduct and misrepresentations to the court."

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Wen_Ho_Lee

Montejo v. Louisiana, 556 U.S. 778 (decided May 26, 2009): statements made after defendant was appointed counsel admissible even though defendant not aware that counsel has been appointed because Miranda warnings were sufficient (overruling Michigan v. Jackson, 1986)

I don't think this is quite correct. The defendant here was brought in for questioning about a murder. He was given his Miranda warnings, which he waived. During questioning, after changing his story several times, he admitted to shooting the victim in a botched robbery attempt. He was brought before a judge who appointed him counsel. The judge had not asked whether he wanted appointed counsel; nor had the defendant requested counsel. He had simply stood mute as the court appointed counsel, as it did automatically as a matter of course.

Later, the police Mirandized him again, and again he waived his rights. The defendant agreed to help police find the murder weapon, which he had earlier indicated he had thrown into a lake. During the trip, he wrote an inculpatory letter of apology to the widow of the victim. This letter was later admitted at his trial at which he was convicted and sentenced to death. The issue before the Court was whether that letter should have been excluded. (Though it seems there was a mountain of evidence besides the letter to sustain the conviction).

So, your summary is essentially correct, but I think the main point is whether a defendant has affirmatively invoked his right to counsel. I think this 5-4 decision is a close call and am not really sure which side I would have come down on.

Thanks. Perhaps I should rephrase.

Andrew Johnson, Zachary Taylor, William H. Harrison, and Jimmuh Cartuh, could be sort of a Reverse Mount Rushmore.

Andrew Johnson was probably the best of the 4, which is saying something.

Frank

The reason Andrew Johnson didn’t get to appoint any Supreme Court Judges is because the Radical Republicans played games with the size of the the Supreme Court, allowing it to shrink as Justices died, to deny Johnson any appointments. They of course reversed this when Grant became President.

Harrison and Taylor didn’t appoint any for obvious reasons, and Carter was an accident. If George W. Bush had lost in 2004, he would have joined Carter.

The surprising thing is that Garfield did appoint a Justice during the few months before Guiteau shot him. He almost didn't get one: The vote on Stanley Matthews was 24 - 23.

Surprising thing about Garfield's Assassin, (besides that he was executed less than a year after shooting Garfield) was...

"Upon his autopsy, it was discovered that Guiteau had the condition known as phimosis, an inability to retract the foreskin, which at the time was thought to have caused the insanity that led him to assassinate Garfield."

Jeez, today he'd get a Phimosis Reduction (or maybe even "Transition") spend a few months in Group/EST at St. Elizabeth's and be set free to stalk Jodie Foster....

Frank

With Johnson, it was reverse court-packing.

Congress passed the Tenth Circuit Act in 1863, which created the new circuit out of California and Oregon and a new tenth justice to preside over it. President Lincoln appointed Stephen Field to the newly-created position. In 1864, Chief Justice Roger Taney died, and Lincoln appointed Salmon Chase to succeed him. This would be the last iteration of the brief existence if the ten-member Court.

In May 1865, a month after Lincoln’s assassination, Justice John Catron died. In April 1866, President Andrew Johnson nominated his Attorney General Henry Stanberry to succeed Catron. In response, Congress passed the Judicial Circuits Act, which gradually reduce the size of the Court to seven as sitting justices died or retired. Johnson signed the act, effectively nullifying his nomination of Stanberry. It is uncertain why Johnson did not veto the act. Perhaps he was just certain Congress would override his veto. (Of his 21 regular vetoes, Congress overrode 15.)

In July 1867, Justice James Moore Wayne died, reducing the membership of the Court to eight. Shortly after President Ulysses S. Grant took office, Congress passed the Judiciary Act of 1869, restoring the membership of the Court to nine, where it has remained ever since. Grant would appoint Joseph Bradley to the newly-created seat.

"(...Hale Boggs) (I remember him — this election started his long career...)"

Do you remember Congresswoman Lindy Boggs, Cokie's mother? Between them, Hale and Lindy Boggs held that Louisiana House seat from 1942 to 1991.

I met her three times in the mid 1980's, at the annual Christmas parties she threw in her huge Watergate co-op. No, not my usual circle...while stationed at Andrews AFB 1980-1986, I sang with the Alexandria Choral Society and as fundraisers, we rented out small groups of ourselves as Christmas party entertainment for the healthy DC party circuit. She paid well and after our 30 minutes plus another 10 leading carols (which she joined lustily), she invited the 7-10 of us to raid the buffet.

Thanks.

Questions arise:

1. Is danger to the community another traditional reason for denying bail (in addition to flight risk)?

2. Was Fat Tony really a danger to the community? Or only to certain “targets”?

3. Would he have made bail if he had put on 100 pounds, limiting his mobility (so as to become Really Incredibly Grossly Fat Tony)?

Watched that whole stupid movie, don't remember a memorable scene. Not saying it's bad, but what's the "Luca B Sleeps with the Fishes" moment??

Frank " Our True Enemy, has something something"

For reasons that I would hope are obvious, thats not an argument for release. The standard is whether any "no condition or combination of conditions will reasonably assure the appearance of the person as required and the safety of any other person and the community". 18 U.S.C. § 3142(e)(1).

At the time of the 1987 SCOTUS decision, Anthony Salerno had been convicted after a jury trial on unrelated charges and sentenced to 100 years' imprisonment. In that the government could have taken him into custody to begin serving that sentence, the case should have been dismissed as moot to Salerno. 481 U.S. 739, 757 (1987) (Marshall, J. dissenting).

The other defendant, Vincent Cafaro, had become an informant and was released on bail with the government's consent in 1986. Id., at 758. The Supreme Court did not have a justiciable controversy before it at the time of the ruling.

How's that?

The traditional right to bail in noncapital cases (see below) hasn't suddenly become outdated with new sociological insights. It's the institutional embodiment of the presumption of innocence.

Considering the safety of the community in deciding whether to release someone is a perfectly reasonable thing to do - if he's been convicted of a crime. If he's only been accused, he's presumed innocent, and by getting into the dangerous Department of Pre-Crime business of imposing what may be heavy sentences on the unconvicted (and pretrial delays can be quite long - I'd hate to see how long they be if there *weren't* speedy trials).

The old common-law device of the peace bond was specifically geared to keeping someone in prison until he posted bond to guarantee his peaceable behavior (as the name of the bond indicates) - merely showing up in court doesn't get him the money back (as in a criminal prosecution) but they have to behave themselves. We could go back to this method...or we could act like Congress in the auspicious year 1984 and invent ways to keep nonconvicted people in prison without trial.

Very interesting...is there a case to be made that the opinion was merely advisory, if the Court had no real dispute to act upon?

No. Chief Justice Rehnquist's rationale was that though Salerno had been sentenced in the other case, he had not yet been confined pursuant to that sentence. The authority for Salerno's incarceration at the time of the decision remained the District Court's pretrial detention order which was under review. 481 U.S. at 744, n.2.

Disingenuous, but the decision remains binding precedent.

I didn't think that would work, after all a decision on the books for a half century where the plaintiff sought the right to do something no longer possible.