The Volokh Conspiracy

Mostly law professors | Sometimes contrarian | Often libertarian | Always independent

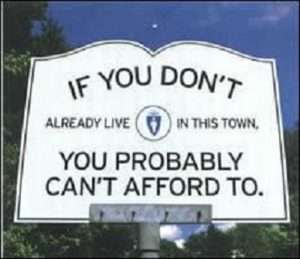

Zoning Restrictions Spread to New Areas, Making Housing Crisis Worse

Harvard economist Edward Glaeser describes a dangerous trend. But a cross-ideological tide of reform might help reverse it.

A broad consensus of experts agree that zoning restrictions on the construction of housing are extremely harmful, and need to be cut back. In a recent City Journal article, Harvard economist Edward Glaeser - arguably the nation's leading scholar on this subject - describes how the problem has gotten worse in recent years, with regulations tightening in many areas:

The overregulation of American housing markets began in the nation's coastal, educated, productive enclaves. Over time, however, barriers to building have spread. Tony suburbs of Phoenix and Austin, which once left their builders free to construct plentiful affordable housing, have now become almost as restrictive as the Boston area.

The expansion of land-use regulations will have an enduring impact on the cost of American housing. The web of restrictions pushes prices up by limiting the number of houses that can be built and deters development through the uncertainty that it creates. Since the permitting process often allows only tiny one-off projects, American builders can't exploit the economies of scale that have made almost every other manufactured good far more affordable.

The consequences of land-use regulations go beyond high housing costs. Since people can't afford to move into areas that don't build, America's most productive places have remained too small. The nation's gross domestic product is therefore lower than it could be with a more rational housing system, and poverty too often gets frozen. Housing-price bubbles are more extreme when the housing stock is fixed, too, so the country courts financial chaos by refusing to make building easier…

While the coasts were the initial epicenters of overregulation, 61 percent of the non-coastal West and 53 percent of the non-coastal East became substantially more regulated between 2006 and 2018. By contrast, 34 percent of the non-coastal East and 28 percent of the non-coastal West reduced regulation; 52 percent of the Sunbelt became more regulated, and 33 percent less regulated……

Across the country, the biggest regulatory changes were seen in minimum lot sizes and the number of entities required to approve any rezoning. In 2006, 28 percent of communities had a minimum lot size of one acre. By 2018, 39 percent of communities in the sample had a minimum lot size greater than one acre. The share of communities where a rezoning required approval by at least three entities went from 22 percent to 45 percent.

This creep of regulation means that restrictive zoning is no longer just a problem for New York and San Francisco. Regulatory curbs on new building are now part of life around much of the United States, and that has pernicious effects that go far beyond just pushing up prices….

This closing of the metropolitan frontier has macroeconomic implications. Again, restricting the supply of something that is in demand will make asset bubbles far more likely—and these, if large enough, can have a massive destructive impact when they burst, as they did in 2007…..

The second macroeconomic point is that restricting housing growth means limiting the movement of poor people to rich, productive places. Throughout our history, Americans have moved in search of economic opportunity….. That process of relocation has slowed greatly because poor people cannot buy or rent homes in the prosperous areas of technological progress, such as Silicon Valley…

Local land-use regulations also make America more unequal. My colleague Raj Chetty and his coauthors have produced an "opportunity atlas" that shows where poor Americans have the best chances of growing up to be successful. Their primary measure of opportunity is the adult income of children whose parents were poorer than three-fourths of their contemporaries at the time when the child was born…. [L]and-use regulations are strictest in areas that offer poor children the most economic opportunity.

The data cited by Glaeser is simultaneously compelling and depressing. It shows that the already severe problem of exclusionary zoning has been getting worse.

If there is some room for optimism here, it's that most of the studies Glaeser cites were conducted too soon to take account of the growing wave of zoning reforms enacted in recent years, such as the abolition of single-family zoning in Oregon, a number of recent enactments in California and Connecticut, and much else. States as varied as New York, Massachusetts, Utah, Montana, and Virginia are in the process of implementing or considering major reforms this year. Progress will be difficult, as there are powerful "NIMBY" ("not in my backyard") interests arrayed against it. Public ignorance of the relevant economics is also a factor.

Nonetheless, it is noteworthy that there is a substantial cross-ideological movement for reform. Glaeser's take on the issue has much in common with that of people as varied as Virginia Republican Gov. Glenn Youngkin and Hawaii Democratic Senator Brian Schatz, who recently made the case for reform in the Slate:

As a Democrat, I come from a long tradition of progressivism based on helping people. But one of the areas where I think the Democrats have it wrong, traditionally, is that we're actually creating a shortage of the thing that we say we want. We are making it incredibly difficult to create housing, and then we sort of puzzle through what to do about it. And the solution is very simple, in fact. We need to make it legal to build housing of all kinds.

This should be attractive to people who are progressive, because we have a massive nationwide housing shortage. But also, people who are right of center should be attracted to the basic property rights argument, which is that, hey, it's your land—you own it.

I couldn't have put it better myself! This is indeed the biggest American property rights issue of our time, more so even than eminent domain abuse, even though I have devoted much of my work to the latter. It's also blocking opportunity for the poor, and thereby stunting economic growth and innovation. And the solution is indeed "to make it legal to build housing of all kinds."

Editor's Note: We invite comments and request that they be civil and on-topic. We do not moderate or assume any responsibility for comments, which are owned by the readers who post them. Comments do not represent the views of Reason.com or Reason Foundation. We reserve the right to delete any comment for any reason at any time. Comments may only be edited within 5 minutes of posting. Report abuses.

Please to post comments

It’s not the zip code that determines successful children. It’s the parents. Biologically intact natural families generally produce successful children. Other configurations generally do not.

And who has to pay the cost of the externalities of putting slums in the suburbs? The section 8 slumlord, or the victims of his taxpayer subsidized tenants?

BCD, you are correct. The cities want to export the inner city's negative externalities to the suburbs so that gentrification can enhance the big city's tax base.

My answer is you created those problems, you FIX them. Do not shove them off on the suburbs. Skip the 3 sports stadiums and invest in YOUR decaying neighborhoods. The big city in my Metropolitan Area has the money but they prefer to buy nice things while pushing the residents of their rotting Wards onto the nearby suburbs. That should not be America's public policy.

BTW, we have light rail to get suburbanites (who no longer work there) to Downtown but the urban planners deliberately routed it around the rotting inner city neighborhoods leaving those residents no transportation to areas where jobs going begging. The Democrat city politicans solution is to destroy the big city's high crime/low employment neighborhoods by exporting the people to somewhere else.

Biologically intact is not enough. 85 IQ African DNA will never lead to successful schools.

Does one Volokh Conspirator -- just one -- have enough character to say something about the routine bigotry that constitutes an important element of this blog?

If not, your children will follow one of two courses:

1) They will be better than you, and will disrespect your cowardice and conservatism.

2) They will be no better than you, and will follow you to America's intolerant and obsolete right-wing fringe, destined to be bitter culture war casualties who hate modern America -- until they are replaced by better Americans.

I hope your children follow the first path.

We are the only ones having children that can procreate.

I grew up in a small town on the Erie canal. The north side was workign class ethnics (Germans, Italians, Irish, Dutch) and the south side more WASPish. Had a huge field across the street from my parents house. Used to fish, play, ride minibikes..then in in the early 70's the NY State Urban Renewal Corporation decided to put in dense public housing. No more field, or streams or fish. A development that looked right out of some East German dream was created and guess what? my parents (working class ethnics) house dropped in value by 50%, the usual public housing degenerates moved in..unwed moms with five kids, druggies, and various losers. I got jumped by some thug when I was 13 in my own yard, my Dad a WW2 combat vet beat the crap out of the guy. Today my Dad would be sent to jail by some Soros commie DA. No, you have the right to decide who lives in your town. Free assoication..you can't afford to buy a modest single family home in my hometown..then better yourself first. End ALL public housing. It just perpetuates bad culture and behavior

Maybe you should save your unhinged rant for a post that actually addresses public housing.

Yeah, the place I lived when I was a kid was right next to a field too, and now it's developed. Not public housing; just a regular development. It happens. Free association does not mean you get to choose who buys the lot next to you.

No. It's not "your" town, and you have no such right. You have the right to decide who lives in your property. "Your" town is not your property. Zoning is about telling other people what they can do with their own property.

And then property owners should collectively have the right to put restrictive covenants in place to stop human excrement from moving in.

But then you'd be in a cardboard box under a bridge.

Another fine example of "democracy" meaning "rule by the Democrat party". Butter clingers have no say in the decisions made by their betters!

What did DMN say that made you think he was saying something partisan, or about dairy products?

over 80% of the village voted against public housing..and NY State shoved it down our throats. Our "betters" who lived in more exclusive areas said it would be good for their kids to associate with the less fortunate (the working-class ethnics I suppose were not the kind of "poor folk" they wanted their kids to know). A town or villlage has every right to decide on their zoning nothing wrong with only allowing single family houses and no apartments.

Yeah, you you live in a village and also a state. A village is not an island.

Though you calling those nasty libby libs in the state bigoted, as you yourself are raging against undesirables.

A town or villlage has every right to decide on their zoning nothing wrong with only allowing single family houses and no apartments.

This paean to structural racism is not true. But you DO have a right to whine on the Internet all you want!

I bought both a house and a neighborhood. Screw with either and you reduce the value of my investment to me. Sorry, Economists, but that investment consists of ROI that is not neatly captured in "market value". I am a multi-millionaire but, like billionaire Warren Buffett, I stil CHOOSE to live in a house and neighborhood I purchased 50 years ago. So do my neighbors as the less than 5% turnover rate demonstrates.

Slums are like rotten apples. Move a portion to a suburb and rot occurs there. All I have to do is match the low price housing map with the increased crime map in my metropolitan area. The overlay is near 100%. The presence of the apple slice does not enhance anyone's life for more than 2 years. That is a fact.

You cannot "improve" a decaying, crime-ridden inner city by spreading the rot. Gentrification in one place means decay in another.

You did not, in fact, buy a neighborhood.

No, he did buy into a neighborhood.

You quip does not actually answer he complaint. But it does respond that externalities change

Having money does not make you immune from changes outside your property.

You can be grumpy about it, you can try and make policies to deal with the core issue. But you have no right to demand nothing in your neighborhood change in 50 years, that's idiotic.

Like most ideologues, Somin cares less for the ostensible topic under discussion than he does to vindicate preferred ideology. With ideologues, backward reasoning can happen. First you establish axioms, then you reason from those to posit facts. Thus with supply and demand axioms for Somin: if more housing gets built, the price of housing will go down. Is that what happens? Somin doesn't know.

Real estate developers who are not ideologues see it differently. They take each deal as a unique factual case, with its own attendant premises. They build accordingly—with an eye to making flexible choices about places, land values, labor availability and costs, materials costs, market demand, building standards, financing costs and availability, politically manipulable regulatory standards, and adjacent or near-adjacent future prospects for more work and more profits. All those and more figure in.

Unsurprisingly, that more-complicated approach does not deliver results which march in lockstep with Somin's simpler ideological expectations. Sometimes developers' calculations deliver results opposite of Somin's expectations—more development sometimes means prices will increase instead of decline. That is an occurrence which delights the developers, and rivets their attention, not to mention the allied attentions of similarly-interested financiers, labor leaders, and politicians. All of those are not merely boosters of development projects, but investors in them, as the developers typically are themselves.

Thus, when Somin calculates results of adding more housing to a particular place, he always knows what will happen—prices will always go down—or they will rise less quickly, or some such ideologically consistent outcome. Naturally, optimistic ideology like Somin's delivers optimistic facts like the ones which fill Somin's imagination.

Somin seems not to consider that one man's optimism may be another man's bad news. Which is a point especially salient among investors.

When a real estate developer makes his kind of calculation, he never knows what will happen, until an extensive factual investigation followed by a lot of mathematicized hypotheses have their say. After that, the developer gets to do something Somin does not reckon into his simplifications—the developer gets to make a choice, whether to build or not. Guess which way the developer chooses, if after calculating he supposes as Somin does, that prices will go down, or maybe just that price increases will be impeded?

Before answering with a Somin-like simplification of your own, consider that the developer's choice is typically made in the alternative, not just for a targeted particular site. The developer isn't looking to vindicate ideology, he isn't looking to make the best of a marginal situation, he is looking for a rare bird and a big score. That is something the developer is more likely to find when ideological expectations break down, which happens. The developer compares many sites, many sets of economic premises, and many ways to develop projects.

Given ability to choose between building in places where development will increase prices, and building in places where development will depress prices, what do you think a developer will choose to do? What choices do you suppose those allied interests—the financiers, the labor leaders, and the politicians—will most readily back?

Somin's repeated reliances on free market ideology get ironically and Quixotically overturned by . . . free market ideology. Turns out, free market ideology is much more about choices than it is about predictable certainties. Thus, free market ideology, put in practice, does a better job to support people who choose with an eye to make prices go up, than it does to support people who choose with an eye to make prices go down.

Observers less ideological than Somin take note of that.

Yes. This has been yet another episode of Simple Answers to Stupid Questions.

True, but SL gave us a looonnngggg simple answer.

No, Nieporent. Adherence to ideology in defiance of facts is a short route to bad decisions.

The places in the U.S. where housing demand is greatest—and thus where demand to reduce prices is felt most keenly—got that way because far more folks want to live in those places than existing housing stocks can accommodate. Those places now feature excess demand so great that no conceivable amount of new development will alleviate it.

They are famous places, and commonplace. They include among others: Portland ME, Portsmouth, NH, eastern Massachusetts in its entirety, numerous places along the Connecticut shore, the New York City Area, Northern New Jersey, Wilmington, DE, Washington, DC, and the central North Carolina region. On the west coast all the major cities are similarly under demand, from Seattle to San Diego. In Texas, Austin has become notorious as a place formerly accessible, and now expensive to access.

I suggest that in none of those places will decreased zoning do anything at all to reduce housing prices. Demand to live in all of them comes from numerous would-be buyers with more wealth than needed to make it convenient to live there. There are many other such places across the nation. Those wealthy buyers know how to bid for what they want.

Geographic constraints apply. To build too far away takes the supposed remedy right out of the demand-affected area. Developers who try that increase their risks, sell for less, and reduce their profits—while encouraging supply-and-demand ideologues to applaud a largely irrelevant decrease in statistical housing prices.

Note also that buyers of mis-located homes in extreme outer-suburbia have not been subtracted from excess urban demand. That is something in which they could never afford to participate in the first place. They expect to pay in commuting costs, service scarcity, health insecurity, and increased investment risk for a housing decision to which they were driven by meager available resources—a decision they would not have made otherwise.

By contrast, to build in the excess-demand places stimulates interest, but cannot clear demand. Newer housing is typically built at higher cost. Sales at increasing prices excite interest still more. Rising prices suggest investment opportunity—even a too-high price can be a bargain, if it keeps increasing. Developers and financiers understand that their activities do stimulate prices. Thus, to invest in their own projects delivers continuing opportunity to profit—and even to profit from the effects of subsequent projects undertaken by others. The history of urban economic booms shows that they become self-sustaining for many decades.

It is against that backdrop that the dynamic introduced by developers’ agency to decide which projects to build, and which projects to shun, must be reckoned. If such practically insatiable housing markets were not commonplace, a would-be developer might indeed have to defer to the discouraging dictates of supply and demand, if only to stay in business. So developers remain delighted that fortune has spared them from such dismal constraint.

Collectively, you can expect developers to respond to any efforts to restrict zoning by confining their activities to areas where that will do nothing to affect housing prices. The excess demand for housing which people want addressed will go unaddressed. It is not a demand for housing in the abstract. It is a demand for housing in places featuring good employment, home investment security, superior educational opportunities, reliable healthcare, and plentiful amenities. For that mix, there is excess demand without practical limit. Given that, developers will simply not decide to build in places where the housing price constraints you and Somin tout seem likely to happen. Such places do not feature the market attractions which create excess demand.

It seems peculiar that self-professed libertarians cannot grasp that developers do business where conditions favor their prospects. Why would developers elect instead to do business in places less favorable? What would make anyone suppose that reduced zoning and lower housing prices would create conditions more favorable to profit from housing development?

It's amazing how many words you can type without actually saying anything. But, no, it's obviously absurd to claim that new development can't meet demand.

I did not say new development cannot meet demand. I said new development would choose not to meet demand at lower prices, if it could continue to supply demand at higher prices.

I suppose a corollary is that no amount of effort to encourage lower-priced supply will prove sufficient to reduce higher-priced demand, so development interests will choose to serve the latter and ignore the former.

A further problem might be that high-priced demand for housing in this nation's more-expensive cities is world-wide, while development capacity to serve that demand is notably less than world-wide. Also, acreage on which to put the product is strictly local, strictly limited, and can be enlarged only at a rate far slower than development can make use of it. The customers who drive the prices up for everyone are mostly not candidates for the exurbs, where more acreage is readily available.

If you loosen zoning restrictions, people might get the insurrectionist idea that they can own property.

Getting rid of zoning, like open borders advocacy, is one of those issues that makes makes most people realize that hardcore libertarians live in cloud-cuckoo land.

While Prof. Somin has talked about opening the borders, I don't know if I've seen him say get rid of zoning. Just that it's too much used right now.

Which I find hard to argue, especially seeing how the pro-zoning advocates who come around and seem to be pretty awful.

"I don’t know if I’ve seen him say get rid of zoning."

Baby steps?

What most of us know but need frequent reminding of (because it seems so obvious) is that the people who impose zoning restrictions and make building permits so complicated, expensive and prolonged do not have benefiting the poor and working classes with plenty of housing options as their primary motivation. They respond to pressure from NIMBY homeowners, affordable-housing Federal grant agencies, organized environmental protection groups and public sector employee unions. Their only goal is to get elected, re-elected or move up the career ladder as elected officials, not to make progressive programs achieve progressive goals based on facts, logic or real-world experience.

Yes. I'm an individualist and therefore like the zoning restrictions and complex permitting requirements that help maintain or increase the value of the property I own.

Welcome to Galt's Gulch.

Zoning originated on Manhattan Island to keep Jews from living in neighborhoods where they were unwelcome. That alone ought to inform the professors, legislators, and judges who support this government-authorized taking of land development opportunity without compensation. The most adequate comparison of the effect of zoning is between Los Angeles and Houston, where patterns of land use are virtually indistinguishable. Evidently, the principal difference between the two jurisdictions is that Houston lacks officials to bribe for spot-zoning and variances.

Or else it lacks Jews.

I do understand the bad effects of overzealous zoning. But I also had to move away from an area because of uncontrolled development and sprawl, changing it from rural to highly developed suburban. I don't know what the solution should be, but I would hope it would lie somewhere in the middle between the two poles.

As always, don't say, "NIMBY." It's a morally dubious term, mostly chosen to shame folks who are trying to protect themselves from uncompensated losses, usually inflicted by government. I am always caught off guard when I hear libertarians use that term. What are they thinking?

They're thinking that people who try to obstruct other people's ability to use their own property as they see fit are disreputable people who should be disparaged.

Blue state, red state, doesn't matter, when it comes to property values everyone is a conservative.

No, just the NIMBY people are loud.