The Volokh Conspiracy

Mostly law professors | Sometimes contrarian | Often libertarian | Always independent

Today in Supreme Court History: January 29, 1923

Editor's Note: We invite comments and request that they be civil and on-topic. We do not moderate or assume any responsibility for comments, which are owned by the readers who post them. Comments do not represent the views of Reason.com or Reason Foundation. We reserve the right to delete any comment for any reason at any time. Comments may only be edited within 5 minutes of posting. Report abuses.

Please to post comments

Marchetti v. United States, 390 U.S. 39 (decided January 29, 1968): I didn't know until I read this case that something can be against the law and still be taxed. "Wagering" (handling bets) is (or was) an example. Not only did (do?) "wagerers" have to pay taxes, they were required to register and publicly post their licenses. Defendant here refused to do any of this, citing the Fifth Amendment privilege against self-incrimination. The Court agrees, noting that the information gathered by the statutory scheme is used by prosecutors, and holding that asserting the privilege is a complete defense. (In other words, I admit that I broke the law and therefore you can't prosecute me.) The Court notes "different" circumstances where "a taxpayer is not confronted by substantial hazards of self-incrimination", but I can't imagine how that would ever be true if the taxed activity is illegal.

Haynes v. United States, 390 U.S. 85 (decided January 29, 1968): decided the same day as Marchetti, with a similar situation. Small firearms, i.e., capable of being concealed, were presumed to be used "principally by persons engaged in unlawful activities", and therefore were subject to special taxation and registration requirements. Also included were small firearms actually constructed by the owner. Ownership of an unregistered firearm is a criminal offense. (The statutes, 26 U.S.C. §§5841 and 5845, are still in force.) The Court here holds that one cannot register a small firearm without incriminating oneself, because the registration requirements include providing personal information and whether he has ever been convicted of a crime; therefore it reverses a conviction for ownership of an unregistered firearm as defined.

United States ex rel. Lowe v. Fisher, 223 U.S. 95 (decided January 29, 1912): Descendants of former slave of Cherokees had no claim because he did not return to reservation (and get his allotted land) within six-month deadline set by Court of Claims. The opinion has an interesting historical discussion of tribes' attitudes towards being forced to give up their slaves; whether freed black people should have the same rights as tribesmen; and how Congress dealt with the issue over the years.

Teitel Film Corp. v. Cusack, 390 U.S. 139 (decided January 29, 1968): Chicago "censor" process violated First Amendment because 1) gave the censor too much time to decide whether a film could be shown and 2) did not provide for prompt judicial review (the films, "Rent-a-Girl" and "Body of a Female", can be found online; they're what "Carnival of Souls" would look like if written by a sex-obsessed 14-year-old boy)

Provident Tradesmens Bank & Trust Co. v. Patterson, 390 U.S. 102 (decided January 29, 1968): owner of car whose insurer was being sued in connection with accident didn't have "absolute, substantive right" to be joined as defendant because joining him was "infeasible" due to destroying diversity and therefore he was not an "indispensable party" under FRCP 19. What?? (my Civ Pro professor complimented Harlan's analysis, but my Complex Litigation prof called this case "incomprehensible", which made me feel better, because this logic seems circular to me, even 34 years later)

Income earned through illegal activities can (and must, in order to avoid potential tax evasion charges) be declared as "miscellaneous income" without directly implicating oneself. And if an IRS agent knocks on your door and asks, "What's this $10 million in miscellaneous income?" you can answer, "I plead the Fifth."

Of course, most criminals aren't going to bother to this because it amounts to a flashing light to law enforcement that says, "Watch me, I'm doing illegal stuff."

That would be different from a box that said "list income from illegal drug dealing [or whatever] here," which is more analogous to the cited case.

About 35 years ago, Maine decided to require tax stamps for marijuana -- then still illegal -- with the intention of taxing confiscated marijuana. I don't remember the exact reason why they were going this route instead of criminal fines, but it made sense at the time. Maine had no intention of ever actually printing the stamps, merely assessing the tax on confiscated marijuana.

But then there were the Philatelics -- stamp collectors -- who wanted to buy these stamps because they collected stamps. Seems that there was no law against paying a tax that one did not owe and last I heard, Maine had to design & print pot stamps to sell to collectors.

Ha!

Other states did the same thing. In Massachusetts your tax stamp was supposed to be affixed to the marijuana at all times. Unless you used the paper to roll a joint it was going to be separated eventually and you would be liable for tax evasion despite paying the tax. The Supreme Judicial Court of Massachusetts ruled that a charge of evading tax on a controlled substance had to be charged in the same indictment as possession or distribution of the substance on which tax had not been paid. Judges probably weren't willing to give defendants longer sentences for the combined crime. Prosecutors gave up.

This is exactly right. Indeed, the principle goes much farther back than 1968- it's how they got Capone for tax evasion.

It's an area where you need a lot of legal advice, and I have no idea how many criminals actually do it. And if you put the wrong thing on your tax return, you can waive your Fifth Amendment right. But yes, you have to (1) make sure you pay your taxes on the income while (2) refusing to report exactly how it was made. If you report it and the IRS wants to audit you they probably would have to offer you immunity to conduct a full audit.

What I don't understand is why the 13th Amendment didn't apply to the Cherokees -- they didn't free their slaves until a treaty was negotiated in 1866, over a year later.

The larger issue is that four(?) tribes were the last slaveowners in America, which sorta runs afoul of the "woe is us'" mantra they'd like us to believe.

the films, “Rent-a-Girl” and “Body of a Female”, can be found online; they’re what “Carnival of Souls” would look like if written by a sex-obsessed 14-year-old boy

Glad to see you put in the time and did the research.

I’m a dedicated person.

I mean, sure you did. The most famous example is Al Capone.

EDIT: (A point I see several other people made before me.)

I knew they got him on tax evasion but I assumed it was as to his “legit” activities.

"The Court notes “different” circumstances where “a taxpayer is not confronted by substantial hazards of self-incrimination”, but I can’t imagine how that would ever be true if the taxed activity is illegal."

Consider the Nebraska tax stamp for importing illegal drugs. It may be purchased anonymously with cash, may (by statute) be purchased for legal purposes such as collecting, and in practice is often purchased by collectors or for novelty. No way is the purchase incriminating.

Since they need only be affixed to the container, not necessarily in a way casually visible, that requirement is also non-incriminating to my eye.

Mind you, the penalty is civil and not too draconian: You pay double tax on anything you're caught with. I don't have a strong opinion on it as policy (I have opinions on what should and should not be a controlled drug, though) but I think it holds up to 5A, and could carry criminal penalties without offending the Constitution.

The Court was busy on this day in 1968!

The way I understand it -- which might be wrong -- is that that's exactly what the Feds finally got Al Capone on.

Bootleggers operating in dry states also were supposed to pay taxes.

This included state taxes on alcohol as well as federal income taxes. IIRC, Mississippi used to collect, peacefully, quite a lot money this way.

Specifically, he didn't pay taxes on illegal income.

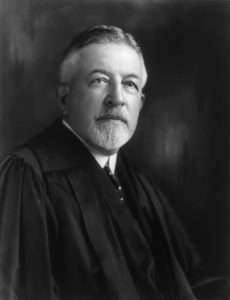

This is at least the fourth time this blog has commemorated Edward Sanford's oathtaking.

I sense this feature is going to continue repeating the flawed installments, too.

Profs. Blackman and Barnett are just mailing it in, recycling envelopes and not even using proper postage at this point. Is Georgetown proud of its association with this?

QuantumBoxCat's observation concerning an earlier iteration of this content:

This blog’s management and fans seem quite content with falsehood and shoddy work.

Carry on, clingers. So far as your betters permit, anyway.

In November 1972, the ABA Journal rated all the justices of the final incarnation of the Taft Court, who sat together from 1925 to 1930. Holmes, Brandeis, and Stone were rated as "great"; Taft and Sutherland were rated as "near great"; and Van Devanter, Mcreynolds, and Butler were rated as "failures". To Sanford alone was reserved the rating of "average".

Obscurity has been the unfair lot of the great Edward Terry Sanford, in great part because he was often seen in the shadow of his friend and mentor, William Howard Taft (no fat joke intended). Sanford was a man of towering intellect, yet a man so affable, everyone seemed to like him. He enrolled in the University of Tennessee at the age of 16, was a member of Phi Beta Kappa, and graduated at the top of his class in two years with two degrees, an A.B. in political science and a Ph.B. After that, at the age of 18, he enrolled at Harvard, earning another A.B. in two years, and an M.A. an LL.B. two years after that. He was also an editor of the Harvard Law Review, which had been founded during his first year in law school.

He took the Tennesse bar exam while still in law school. At the time, the bar exam was still an oral examination, usually conducted by a judge. Sanford's examiner was Horace Lurton, then a member of the Tennessee Supreme Court. Lurton asked Sanford a question about mining interests and was so impressed by Sanford's answer that he giddily went on for thirty minutes about how he had ruled on a similar question in a recent case, declared Sanford the finest applicant to the bar he had ever encountered, seeing no need for any further questions. Twenty years later, when Sanford was sworn in as a federal district judge, it was his friend Horace Lurton, now a member of the U.S. Supreme Court, who would administer his oath.

He was appointed an Assistant Attorney General by Theodore Roosevelt, where he shared the President's enthusiasm for trustbusting, acquiring a reputation for effectiveness and tirelessness in his work. It was here that he began his lifelong friendship with William Howard Taft, Roosevelt's Secretary of War. In this position he also served as the chief prosecutor in United States v. Shipp, 203 U.S. 563 (1906), the only criminal trial ever conducted by the U.S. Supreme Court. Jospeh Shipp was the sheriff of Hamilton County, Tennessee. He and others were charged with criminal contempt of the Supreme Court for allowing a lynch mob to kidnap and murder Ed Johnson, a black man who had been convicted and sentenced to death for the rape of a white woman, while Johnson had a habeas petition before the Court while he was in Shipp's custody. In a 5-3 decision, all the defendants were found guilty. Shipp and two other defendants were sentenced to 90 days imprisonment in the D.C. jail; three other defendants received 60-day sentences.

Sanford initially declined Roosevelt's offer of a district judgeship, averring that he had too much unfinished business in his current position, but eventually relented. He served as the District Judge for the Middle and Eastern Districts of Tennessee from 1908 to 1923. And while he conducted his duties diligently and to the universal acclaim of the attorneys that practiced before him, Sanford longed for a position on an appellate court, which was more suited to his deliberative temperament.

When Justice Mahlon Pitney resigned at the end of 1922, now-Chief Justice Taft lobbied President Harding to appoint his friend Sanford to the vacancy, and Harding acceded. Sanford was very well liked by his fellow justices. Even the old, curmudgeonly Holmes said. "He was born to charm". Sanford was an industrious opinion writer, and though he did not always side with Taft, the press continued to lump them together. Taft would retire from the Court on February 3, 1930. Finally, Sanford would be able to get out of Taft's shadow.

But, alas, Fate had other designs. On Saturday, March 8, 1930, the members of the Supreme Court were gathering at noon to celebrate the 89th birthday of Justice Holmes. Sanford planned to attend, but stopped by the dentist first to have a tooth attracted. After the procedure, he rose from his chair, complained of dizziness, and immediately collapsed. A cart rushed him home, as Sanford muttered, "Twelve o'clock, twelve o'clock..." apparently having in mind the scheduled noon meeting with his colleagues. Edward Terry Sanford would die at home at 12:20 PM, but the media would take little notice because a few hours later that same day, Death would also claim former President and Chief Justice William Howard Taft.

Thanks.

I wonder how the Shipp trial was conducted. Who was the presiding judge? Did the Justices sit like a jury? Or was all the evidence before a special master?

https://famous-trials.com/sheriffshipp/1118-home

Thanks.

So a clerk was appointed to act as a judge!

SCOTUS, as always, tries to avoid original jurisdiction mandates with special masters. A tale as old as time.

I was intrigued by the possibility that just for once a Justice might have actually tried a case.

Rehnquist had never been a trial judge. When he got to be Chief Justice he decided he wanted to see what it was like so a trial was arranged for him. IIRC he did okay but was too liberal in admitting questionable evidence.

Trial judges have to make split-second decisions that will be second-guessed by appellate judges who can spend months thinking after reading thousands of words of briefs.

True!

Lost in DC one night, I came across a major fountain & monument to "Taft" -- looking it up, I see it is to his *son.* Someone I've never heard of.... https://www.aoc.gov/explore-capitol-campus/art/robert-taft-memorial-and-carillon

Richard Nixon said in a 1983 interview that Bob Taft was the best politician he ever saw.

Senator Robert Taft was known as "Mr. Republican", and, as the standard-bearer for the conservative wing of the party was the chief rival of Dwight Eisenhower, who was favored by the moderate and liberal wings of the party, for the presidential nomination in 1952. The first ballot at the convention was 595 for Eisenhower, 500 for Taft, 81 for Earl Warren, 20 for Earl Stassen, and 10 for Douglas MacArthur, putting Eisenhower just shy of the 604 needed for a majority. The Stassen delegates switched to Eisenhower, and Taft moved that Eisenhower be unanimously nominated by the convention, which he was. Taft loyally backed Eisenhower through the campaign.

Taft had been diagnosed with cancer, which he kept from the public, and died on July 31, 1953. So, had he been elected President in 1952, his tenure would have been short.

" Neither slavery nor involuntary servitude, except as a punishment for crime whereof the party shall have been duly convicted, shall exist within the United States, or any place subject to their jurisdiction."[emphasis added]

Indian territory was subject to US jurisdiction, and there is no mention of the citizenship of the slave owner.

The legal relationship between the U.S. government and the Indian tribes has always been murky at best. Essentially, as things have developed, they are treated as sovereign nations, though Congress can take away any or all their sovereignty as it pleases.

The Thirteenth Amendment would not have been seen as applying to the Indian tribes any more than any of the Bill of Rights was. Indian tribes were not under any obligation to guarantee freedom of speech or religion, refrain from unreasonable searches or seizures, guarantee a speedy trial, etc., until these and several other elements of the Bill of Rights were included in the Indian Civil Rights Act of 1968.

Would someone be so kind as to explain "jurisdiction" of the US as regards its use in the Constitution and in law?

Thanks!

Indeed -- until 1871, the United States regularly made treaties with Indian tribes. Congress stopped then as a broad matter of government policy, but that was still several years after what Dr. Ed asked about.

Reading pre-Heller gun cases is a strange experience. I’m never sure if they would be decided differently today. Some seem quite restrictive, but none have been explicitly overruled (at least not the ones I’ve commented on).

Yes — the Indian Appropriation Act of 1871 — https://coloradoencyclopedia.org/image/indian-appropriations-act-1871

But in the 19th Century, US States were also seen as largely sovereign and here was the 13th (and 14th/15th) Amendment imposing major infringements on what had traditionally been considered state’s rights/state authority.

A sovereign nation, e.g. Mexico, is free to ally itself with hostile foreign governments, as Mexico allegedly tried to do during WWI. And during the 18th Century (actually up through the War of 1812), some of the Indian Tribes did exactly that — allying first with the French and then the British.

But what I don’t understand is that once the “Indian Territory” was formally declared to be a US territory, why the army which had imposed a ban on slavery by White persons didn’t just continue into the Cherokee/Creek/etc villages and ban it there, too. Yes, there likely were language barriers, but still…

NB: US Territory as opposed to British/Canadian or French Territory.

I’ve learned a great deal here.

One case you posted recently had the court deciding long guns could be regulated as because they were only used for hunting. A handgun restriction would have judged more harshly because you could use a handgun in self-defense. By the 1980s or 1990s there was a popular argument that guns should be regulated in the opposite way, with long guns legal and handguns banned.

You might be thinking of:

“United States v. Powell, 423 U.S. 87 (decided December 2, 1975): 18 U.S.C. §1715, criminalizing mailing of concealed-carry-capable weapons to general public (for example, defendant’s 22-inch sawed-off shotgun), was not unconstitutionally vague (so far as I know, this statute survives Heller and McDonald)”

Takes me back to my childhood, when there were so few gun laws that you could literally buy anti-materiel rifles mail order through ads in the backs of magazines. And I could have afforded one, too! Pity I didn't, it would have been a great collectable by now.

It was a very different country before the gun control movement started getting traction.