The Volokh Conspiracy

Mostly law professors | Sometimes contrarian | Often libertarian | Always independent

Freedom Denied Part 4: Judges Must Follow the Correct Legal Standard in Presumption-of-Detention Cases …

to reduce racial disparities and high federal jailing rates.

Our Federal Criminal Justice Clinic's recent national report on federal pretrial detention—Freedom Denied—revealed a severe misalignment between the Bail Reform Act's requirements and on-the-ground practice. In the preceding two posts, we focused on the Initial Appearance hearing. This post now turns to the Detention Hearing.

This post addresses the third of our four findings and recommendations: "Judges must follow the correct legal standard in presumption-of-detention cases to reduce racial disparities and high federal jailing rates."

The Bail Reform Act clearly favors pretrial release in most cases. At the Detention Hearing, a person must be released unless "the judicial officer finds that no condition or combination of conditions will reasonably assure the appearance of the person as required and the safety of any other person and the community." 18 U.S.C. § 3142(e). But the Act contains a rebuttable presumption of detention for some crimes—most federal drug offenses and § 924(c) gun charges.

This presumption was intended to apply extraordinarily narrowly:

Congress intended this presumption of detention to capture only the "worst of the worst" offenders. "[L]egislators wanted the drug presumption to prevent rich people suspected of high-level drug trafficking from fleeing." But in practice, the presumption now applies in a high percentage of federal cases—including 93% of federal drug cases—very few of which pose any special risks of flight or recidivism.

As a legal matter, the presumption should have, at most, a limited effect:

[C]ase law emphasizes two checks that the BRA and the Constitution impose on the presumption: (1) there is an easy-to-meet standard for rebutting the presumption and the prosecution always bears the burden of persuasion, and (2) the presumption alone does not warrant detention and must always be weighed along with other factors.

But our study revealed that judges often eschew these legal requirements in favor of misguided courtroom practices:

Even though judges have the power and legal responsibility to limit the impact of the presumption of detention, they seldom do. Instead, our research shows that judges routinely ignore the legal checks that the BRA provides and give the presumption of detention more weight than the law allows. This appears to be a nationwide problem, as our courtwatching data were supported by interviews with stakeholders in many additional districts. This misuse of the presumption causes many more people to be incarcerated pending trial than necessary and results in stricter conditions of release in the rare cases where people obtain release. These impacts also contribute to racial disparities in the federal criminal system, since people of color face presumption charges more often than white arrestees.

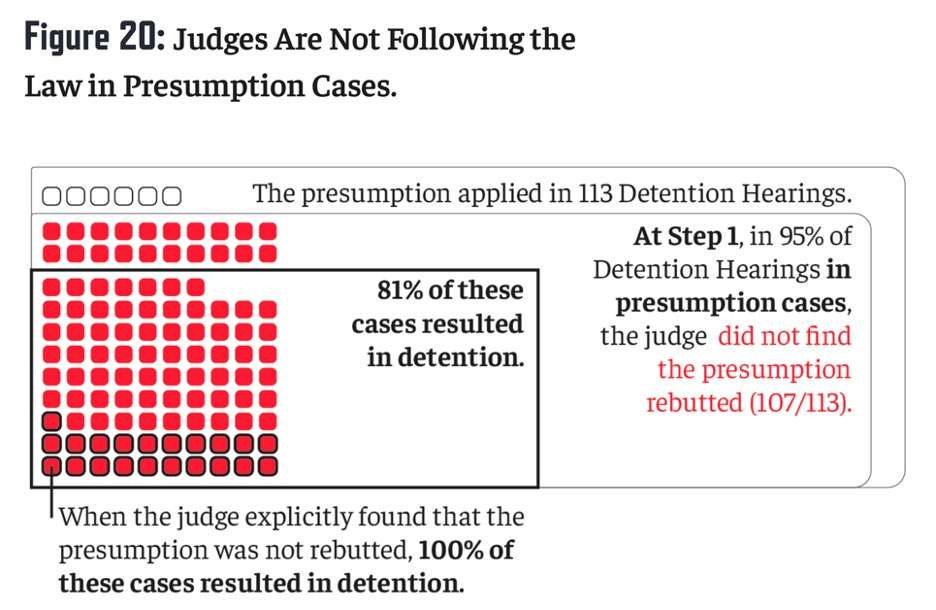

Although the presumption is supposed to be easily rebutted, our research showed that judges rarely find the presumption rebutted:

[I]n 95% of presumption cases that held a Detention Hearing in our study, judges either concluded that the arrestee had failed to rebut the presumption or did not mention whether the presumption was rebutted.

When we asked a judge from a district where we had court-watched why it is so rare for courts to find the presumption of detention rebutted, the judge explained: "I don't understand [the presumption]…. I really don't think judges, including this judge, even though I did some research into trying to understand what it means—what does it mean? What do you need to provide to rebut it? I don't think that's litigated enough. I think that it needs to be brought to the court's attention more often to know what standard applies." This sentiment was echoed in a Detention Hearing we observed, in which the presiding judge remarked: "Candidly, I don't know whether the presumption is rebutted or not. Case law is murky as to what level of evidence is required to rebut …. I don't know if that is met here. So, I'll just base this [detention order] on preponderance of evidence that there is no condition that would prevent flight."

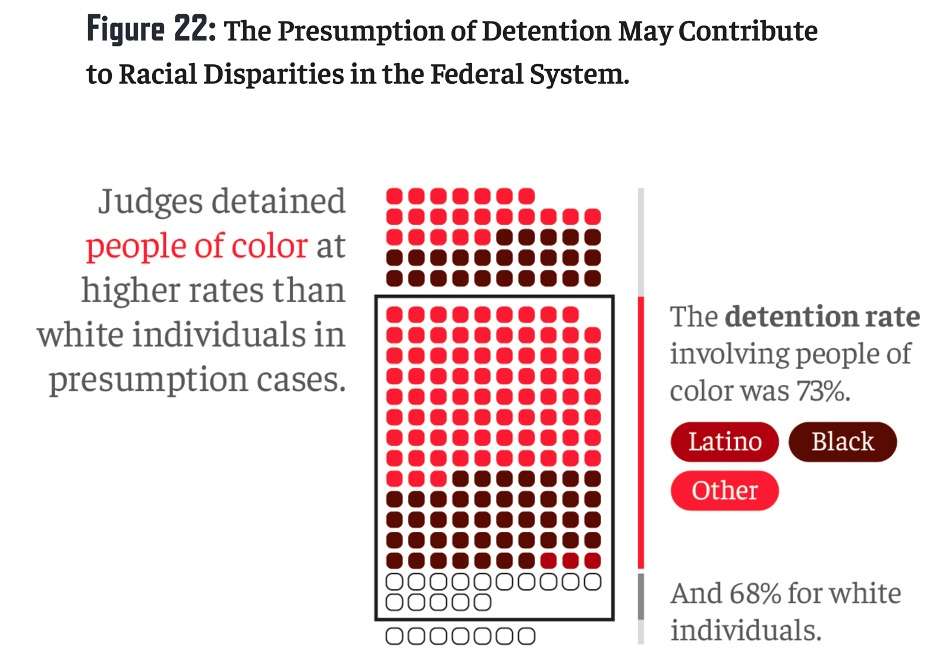

The presumption also has disparate effects for people of color:

The presumption is especially pernicious for people of color because the offenses to which it is tied can dovetail with racial disparities and stereotypes. One judge spoke candidly about this problem. "[A]nother type of case we get in our district a lot are … so-called 'gang cases,'" the judge remarked, "and I think there's a lot of racism involved in calling someone a gang member and then arguing about their dangerousness. Because as soon as you label someone that way, the thought that comes into … a judge's mind is, 'Oh, this person is violent. They're living the kind of lifestyle of violence and committing crimes and that type of thing.' … [O]ne of the things I think is really important to do is not to have things devolve into these types of meaningless labels."

Our data support the idea that the presumption may fall even more heavily on arrestees of color….

[In presumption cases,] judges detained people of color at higher rates than white individuals: the detention rate in presumption cases involving people of color was 73%, while the detention rate in presumption cases involving white arrestees was just 68%.

"The Solution: At the Detention Hearing, Judges Must Adhere to the Low Standard for Rebutting the Presumption of Detention and Never Treat the Presumption as a Mandate for Detention."

[Caselaw establishes a two-step framework for judges in presumption cases:]

At Step 1, the judge should make a finding about rebuttal. As a matter of law, if the defense has presented "some evidence" of the arrestee's history and characteristics (such as ties to the community, family ties, or employment) or some evidence that mitigates the circumstances of the offense, the judge should find the presumption rebutted. If the defense has not presented any evidence, the judge should examine the Pretrial Services Report to determine if there is any evidence that "rebuts" the presumption. Following this first step in every presumption case will limit the damage the presumption causes, minimizing its weight from the outset—as Congress intended.

At Step 2, the judge should consider all of the § 3142(g) factors together, viewing the presumption as, at most, just one factor in the mix—and never treating the presumption as the determinative factor. The judge should recognize that the existence of a rebutted—or even an unrebutted—presumption does not limit their discretion to release. The rebuttable presumption must never operate like a mandatory minimum or a mandate for detention.

Congress can also take action to address the pernicious effects of the presumption of detention. Senator Durbin's Smarter Pretrial Detention for Drug Charges Act of 2021 would advance this goal by eliminating the presumption of detention in all federal drug cases. Such reform is necessary given a government study showing that the presumption results in the unnecessary jailing of low-risk individuals and "has contributed to a massive increase in the federal pretrial detention rate, with all of the social and economic costs associated with high rates of incarceration."

All block-quoted material comes from the Clinic's Report: Alison Siegler, Freedom Denied: How the Culture of Detention Created a Federal Jailing Crisis (2022).

Show Comments (44)