The Volokh Conspiracy

Mostly law professors | Sometimes contrarian | Often libertarian | Always independent

Freedom Denied Part 4: Judges Must Follow the Correct Legal Standard in Presumption-of-Detention Cases …

to reduce racial disparities and high federal jailing rates.

Our Federal Criminal Justice Clinic's recent national report on federal pretrial detention—Freedom Denied—revealed a severe misalignment between the Bail Reform Act's requirements and on-the-ground practice. In the preceding two posts, we focused on the Initial Appearance hearing. This post now turns to the Detention Hearing.

This post addresses the third of our four findings and recommendations: "Judges must follow the correct legal standard in presumption-of-detention cases to reduce racial disparities and high federal jailing rates."

The Bail Reform Act clearly favors pretrial release in most cases. At the Detention Hearing, a person must be released unless "the judicial officer finds that no condition or combination of conditions will reasonably assure the appearance of the person as required and the safety of any other person and the community." 18 U.S.C. § 3142(e). But the Act contains a rebuttable presumption of detention for some crimes—most federal drug offenses and § 924(c) gun charges.

This presumption was intended to apply extraordinarily narrowly:

Congress intended this presumption of detention to capture only the "worst of the worst" offenders. "[L]egislators wanted the drug presumption to prevent rich people suspected of high-level drug trafficking from fleeing." But in practice, the presumption now applies in a high percentage of federal cases—including 93% of federal drug cases—very few of which pose any special risks of flight or recidivism.

As a legal matter, the presumption should have, at most, a limited effect:

[C]ase law emphasizes two checks that the BRA and the Constitution impose on the presumption: (1) there is an easy-to-meet standard for rebutting the presumption and the prosecution always bears the burden of persuasion, and (2) the presumption alone does not warrant detention and must always be weighed along with other factors.

But our study revealed that judges often eschew these legal requirements in favor of misguided courtroom practices:

Even though judges have the power and legal responsibility to limit the impact of the presumption of detention, they seldom do. Instead, our research shows that judges routinely ignore the legal checks that the BRA provides and give the presumption of detention more weight than the law allows. This appears to be a nationwide problem, as our courtwatching data were supported by interviews with stakeholders in many additional districts. This misuse of the presumption causes many more people to be incarcerated pending trial than necessary and results in stricter conditions of release in the rare cases where people obtain release. These impacts also contribute to racial disparities in the federal criminal system, since people of color face presumption charges more often than white arrestees.

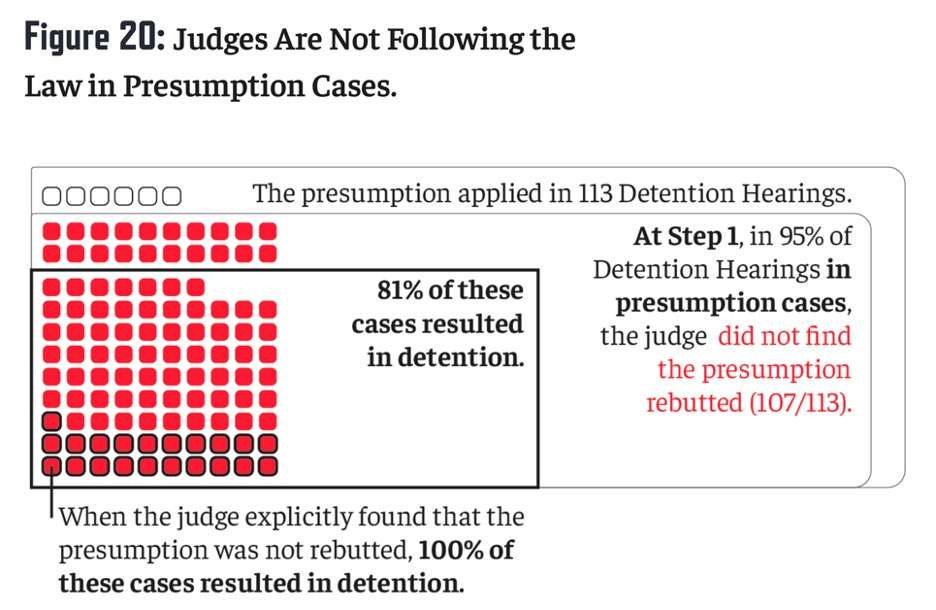

Although the presumption is supposed to be easily rebutted, our research showed that judges rarely find the presumption rebutted:

[I]n 95% of presumption cases that held a Detention Hearing in our study, judges either concluded that the arrestee had failed to rebut the presumption or did not mention whether the presumption was rebutted.

Our interviews with judges revealed a striking lack of awareness about how the presumption is legally supposed to operate:

Our interviews with judges revealed a striking lack of awareness about how the presumption is legally supposed to operate:

When we asked a judge from a district where we had court-watched why it is so rare for courts to find the presumption of detention rebutted, the judge explained: "I don't understand [the presumption]…. I really don't think judges, including this judge, even though I did some research into trying to understand what it means—what does it mean? What do you need to provide to rebut it? I don't think that's litigated enough. I think that it needs to be brought to the court's attention more often to know what standard applies." This sentiment was echoed in a Detention Hearing we observed, in which the presiding judge remarked: "Candidly, I don't know whether the presumption is rebutted or not. Case law is murky as to what level of evidence is required to rebut …. I don't know if that is met here. So, I'll just base this [detention order] on preponderance of evidence that there is no condition that would prevent flight."

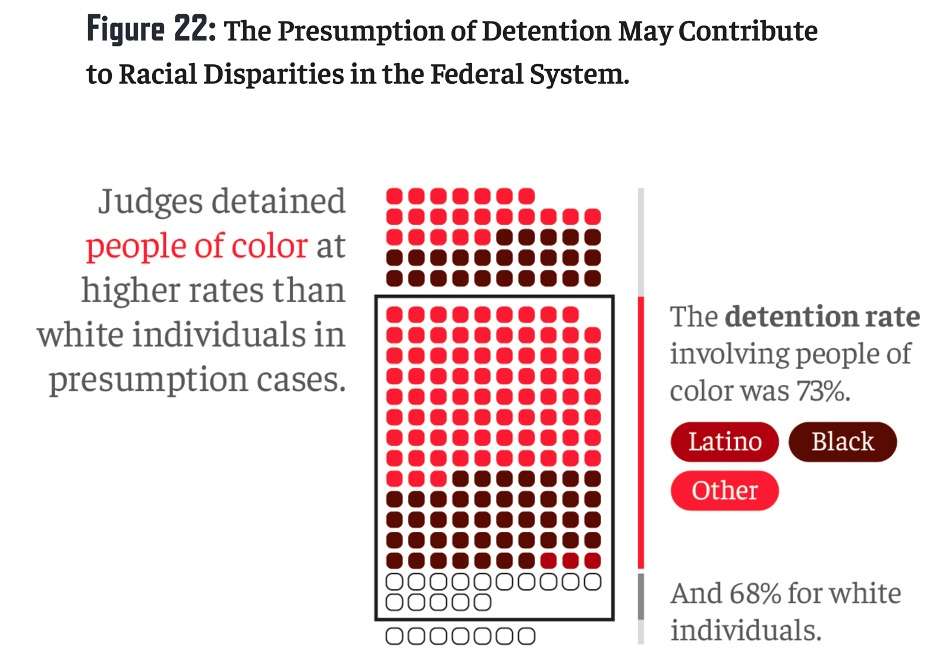

The presumption also has disparate effects for people of color:

The presumption is especially pernicious for people of color because the offenses to which it is tied can dovetail with racial disparities and stereotypes. One judge spoke candidly about this problem. "[A]nother type of case we get in our district a lot are … so-called 'gang cases,'" the judge remarked, "and I think there's a lot of racism involved in calling someone a gang member and then arguing about their dangerousness. Because as soon as you label someone that way, the thought that comes into … a judge's mind is, 'Oh, this person is violent. They're living the kind of lifestyle of violence and committing crimes and that type of thing.' … [O]ne of the things I think is really important to do is not to have things devolve into these types of meaningless labels."

Our data support the idea that the presumption may fall even more heavily on arrestees of color….

[In presumption cases,] judges detained people of color at higher rates than white individuals: the detention rate in presumption cases involving people of color was 73%, while the detention rate in presumption cases involving white arrestees was just 68%.

"The Solution: At the Detention Hearing, Judges Must Adhere to the Low Standard for Rebutting the Presumption of Detention and Never Treat the Presumption as a Mandate for Detention."

[Caselaw establishes a two-step framework for judges in presumption cases:]

At Step 1, the judge should make a finding about rebuttal. As a matter of law, if the defense has presented "some evidence" of the arrestee's history and characteristics (such as ties to the community, family ties, or employment) or some evidence that mitigates the circumstances of the offense, the judge should find the presumption rebutted. If the defense has not presented any evidence, the judge should examine the Pretrial Services Report to determine if there is any evidence that "rebuts" the presumption. Following this first step in every presumption case will limit the damage the presumption causes, minimizing its weight from the outset—as Congress intended.

At Step 2, the judge should consider all of the § 3142(g) factors together, viewing the presumption as, at most, just one factor in the mix—and never treating the presumption as the determinative factor. The judge should recognize that the existence of a rebutted—or even an unrebutted—presumption does not limit their discretion to release. The rebuttable presumption must never operate like a mandatory minimum or a mandate for detention.

Congress can also take action to address the pernicious effects of the presumption of detention. Senator Durbin's Smarter Pretrial Detention for Drug Charges Act of 2021 would advance this goal by eliminating the presumption of detention in all federal drug cases. Such reform is necessary given a government study showing that the presumption results in the unnecessary jailing of low-risk individuals and "has contributed to a massive increase in the federal pretrial detention rate, with all of the social and economic costs associated with high rates of incarceration."

All block-quoted material comes from the Clinic's Report: Alison Siegler, Freedom Denied: How the Culture of Detention Created a Federal Jailing Crisis (2022).

Editor's Note: We invite comments and request that they be civil and on-topic. We do not moderate or assume any responsibility for comments, which are owned by the readers who post them. Comments do not represent the views of Reason.com or Reason Foundation. We reserve the right to delete any comment for any reason at any time. Comments may only be edited within 5 minutes of posting. Report abuses.

Please to post comments

Using the phrase "worst of the worst" in successive posts really undermines the argument when the actual list of eligible charges include any crime of violence, any drug crime with a long sentence, any felony involving a child, firearm, destructive device or "other dangerous weapon", a third strike, serious risk of flight or obstruction of justice, and more. If those are the "worst of the worst" offenses, how low is the bar for mere "worst" offenses, and how shockingly low is the bar for other offenses?

I think the actual answer is the presumption of detention statute is a classic example of something that is very common in legislation– an attempt by the legislature to have it both ways.

On the one hand, they wanted the BRA to pay lip service to the idea that only strong showings of flight risk or dangerousness could justify denial of bail. On the other hand, they didn’t want some very bad guy to get let out on bail because the high standard couldn’t be met. So they passed a self-contradictory statute. And of course, Congress is way too dysfunctional to fix something like this.

What probably should have happened is the Eighth Amendment should have been interpreted to require stringent showings to deny bail, and prohibiting presumptions like this except in situations where they were traditionally allowed (e.g., capital cases). But SCOTUS blessed the Bail Reform Act in the Salerno case, and we are left with this mess.

Does it matter? They could write whatever they wanted, but the actual facts on the ground are going to go how they're going to go, regardless. SCOTUS said that the issuance of no knock warrants require individualized determinations by judges; they can't just say, "It's a drug case, so… granted." But of course in the real world, that's exactly what judges do say.

It depends on how much effort SCOTUS wants to put in to policing the rule.

I'll give you an example- the Ninth Circuit and its District Courts spent a lot of time not strictly adhering to AEDPA. A lot of the judges out here thought it was a bad statute (I basically agree that it is) and decided they were going to make every effort to get around it. SCOTUS saw that, a majority of the Justices thought this was bad, so they started granting cert on a bunch of 9th Circuit habeas cases and sometimes even summarily reversing, until the 9th Circuit finally got the message.

SCOTUS can do that if it sees the issue as a priority. SCOTUS did not want to get involved in that way in the bail system, despite the express terms of the Eighth Amendment.

(But as I said, the central villain here was Congress, for passing a contradictory statute.)

[citation needed]

Here's just one recent example. It sure looks like 9th Circuit is applying AEDPA the way SCOTUS wants it to now.

https://webcache.googleusercontent.com/search?q=cache:EegiNUf26kIJ:https://cdn.ca9.uscourts.gov/datastore/opinions/2022/09/06/20-16800.pdf&cd=1&hl=en&ct=clnk&gl=us

I was mostly joking, of course, and they are getting better, but there's a wide gulf between "getting it better than in the Reinhardt days" and "getting it right".

How can you read the eighth amendment to say anything at all about denying bail?

No bail is the same as setting bail at infinity. It's absolutely ridiculous to say that a provision that prohibits excessive bail does not prohibit bail denial.

In any event, even if you want to take that position, that would just mean we'd need to interpret the Due Process clause to prohibit the deprivation of liberty of presumptively innocent arrestees without specific showings. Either way you get to the same place.

I don't think that's right. "Excessive" is not an absolute term; it's a relative one. Excessive in relation to what? Presumably, excessive in relation to what's necessary to serve the purpose of bail, given the facts of the case. If the charge is jaywalking, then $500 may be excessive; if it's killing someone, then $500,000 may not be. And if it's espionage, then ∞ may not be.

I don't deny that infinity bail is sometimes constitutional. I am refuting the argument that the Excessive Bail Clause does not apply at all as long as the Court just denies bail.

Your refutation is unsuccessful.

Isn’t that precisely the authors’ point?

The authors' point seems to be that courts are implementing bail in a wide variety of cases (and not following procedure), in violation of Congress's asserted intent. But if courts are applying the substance of the rule that Congress actually wrote into law, I think the authors' criticism leaves out key context.

How is it that there is no VC article on the Sixth Amendment violation currently happening to hundreds of detainees in the DC jails following the demonstration at the Capitol on January 6, 2021?

The Volokh Conspiracy seems to have the insurrection filed "on the down low."

For the same reason there is no VC article about the vicious battle between the unicorns and leprechauns that has been raging on the streets of Sheboygan, Wisconsin for the past three months.

Heh, Sheboygan.

This series has been very worthwhile. Thank you.

Sadly statements such as “the correct legal standard in presumption-of-detention cases to reduce racial disparities” and “The presumption also has disparate effects for people of color:” greatly diminish the value of this article.

It's almost as if the authors are arguing that Judges should check the race/ethnicity of previously detained defendants prior to deciding on whether or not to detain the current defendant.

We have a Judicial Conference of the United States chaired by Chief Justice Roberts. It sounds like we have a lack of leadership from them.

In some cases doctrine comes to the lower courts via SCOTUS decisions. But in cases like in these blog posts, shouldn't it come in the form of directives and education from that Judicial Conference?

Wiki says, "Even though the Federal Rules of Evidence are statutory, the Supreme Court is empowered to amend the Rules, subject to congressional disapproval." I assume the same applies to the other Federal Rules.

"But in practice, the presumption now applies in a high percentage of federal cases—including 93% of federal drug cases—very few of which pose any special risks of flight or recidivism."

I'd like to see some evidence of a lack of recidivism. The majority of these cases seem to be drug cases, likely drug distribution or possession with intent to distribute, i.e. drug dealing.

People who commit these crimes are, for the most part, professional drug dealers. That is their job, for want of a better term. When they get out of jail, they return to their jobs, so they can make money.

Of course, recidivism does not seem to be relevant to the pre-trial detention analysis, but I'm not the one who brought it up.

I assume the authors are using “recidivism” to mean “violating release conditions”, or perhaps “committing a new crime while on release”.

I would estimate the likelihood of a drug dealer returning to drug dealing while out on bail at close to 100%. I would welcome evidence that arrest and bail sets them on the path of righteousness (or at least non-drug-dealingness), but I have not seen much so far.

In what context do you observe the relevant conduct?

Are you a frequent purchaser of drugs? Are you a drug dealer?

Do you work in law enforcement or spend time in West Virginia?

Are you an avid consumer of Law and Order, Blue Bloods, and Last Man Standing reruns?

Do you watch a bunch of Fox News, One America, Newsmax, the National Desk, QAnon videos, and NewsNation?

I agree with the authors that the case law on the presumption of detention is largely incoherent. That said, the case that it’s being improperly applied in a way that harms defendants seems pretty underwhelming here: in the one concrete example given, it sounds like the judge ignored the presumption altogether, which makes the situation more favorable for a defendant. I am also unclear whether the report is saying it would be a good idea for judges to independently search for evidence to rebut the presumption if the defense doesn’t come foreword with any, or if the claim is that it is in fact legally required under current doctrine and if so what their authority for that proposition is—the report’s inexplicable choice to put its citations in endnotes doesn’t help on that point, of course.

Finally, I note that the authors have yet to address the glaring issue that was noted multiple times in their first posts: the fact that a high detention rate isn’t necessarily cause for concern, given the obvious correlation between factors that appropriately make someone a more likely target for federal prosecution and the factors that legitimately justify pretrial detention. I grow less optimistic that we’re going to see this core assumption articulated, much less justified.

I agree they should address your last point, but I don't think it is as strong a point as you are implying.

Basically, all pre-trial detention is a gross, horrible infringement on freedom, because every time the system interferes with the liberty of an innocent person for even one second it is a terrible wrong that can never be undone.

If you have any doubt about what I just wrote, compare the way the tort and criminal justice systems treat false imprisonment and assault. There's no "de minimis" defense. Physically restraining someone's liberty is one of the fundamental evils that a free society is supposed to try and prevent.

So the rule that allows pre-trail detention of flight risks and people who pose particular danger is not some free floating power of the government to just keep in prison anyone one might think to be dangerous. It's a highly limited power. It is supposed to almost never happen.

And against that backdrop, a statement that "perhaps it should happen a little more often in the federal system because federal crimes are on average more serious and charges on average more well founded" is, I will concede, a point, but not a very strong one given the absolute numbers here.

And that's especially true when it comes to drug offenses, the subject of this post. Unless a particular alleged drug offender has a specific record of prior VIOLENCE, it should literally never be the case that public safety can't be secured by using monitoring devices rather than jailing the person.

I would also note that despite the confidence of some, federal prosecutors actually charge lots of innocent people. One out of every seven defendants gets acquitted. So when you are applying presumptions, you are almost certainly imprisoning the innocent.

And I will close with a point I always made about Justice Scalia's disgusting, murderous opinion (the worst in his entire career) in Herrera v. Collins. Just like it is easy for Scalia to advocate executing innocent people knowing he and his friends won't be executed, it's easy for people here to advocate imprisoning innocent people knowing that folks of our social class and standing will never be among them. If you think it is OK to jail an innocent person for months or years, you should volunteer to be that person. As Kant pointed out, humans are not means to an end.

So the rule that allows pre-trail detention of flight risks and people who pose particular danger is not some free floating power of the government to just keep in prison anyone one might think to be dangerous. It’s a highly limited power. It is supposed to almost never happen.

I'm not quite sure whether you are freely floating from should-land into is-land here. (A fault in this series of articles too.)

In is-land the 8th Amendment's prohibition of "excessive bail" is somewhat vague, in that "excessive" is open to a wide range of interpretations in different circumstances. But the prohibition itself

1. plainly contemplates that pre-trial detention and

2. refers only to the excessiveness of bail, and says nothing at all about, and imposes no limitation on, what offenses should attract pre-trial detention

If there is a constitutional rule that pre-trial detention is only permissible for "worst ot the worst" offenses, it is one of those silent, penumbral ones. There's nothing in the text about it.

As to should-land, that's another matter. I have some sympathy with your indignation, in theory, but in practice I'm a bit more relaxed. IMHO it would not be an offense against liberty if anyone previous convicted of a crime of the requisite seriousness was, as part of the sentence for the previous offense, exposed to pre-trial detention when accused of subsequent offenses. Saving my indignation at pre trial detention for the pristinely innocent - ie those who had never been convicted.

In practice, I suspect that the vast majority of the folk whose pre-trial detention provokes your indignation are prior offenders.

"There’s nothing in the text about it."

What's the 9th Amendment, chopped liver?

And how about the due process clause, which specifically prohibits deprivations of liberty without due process of law?

It's very obvious to me that "excessive bail" applies to bail set at infinity just as it does to any other bail. But if people really want to rely on the silly, hyper-technical counter-argument, it's still ridiculous to say that a Constitution replete with protections against restraint and imprisonment is just fine with indefinite detention of the innocent.

Your interpretation of due process would seem to exclude arrest.

Even Siegler and Lessnick might be surprised by that.

If you think they meant "infinite bail" then why would they have written "excessive bail" ?

The Bail Reform Act provides the process that is due before someone is detained.

Who said anything about indefinite?

Due process contains a substantive component, and this is absolutely a perfect example of why.

I'm not sure the 9th Amendment is a magic wand that can summon rights from the aether. I think you have to make an effort to demonstrate that the right you would like to summon was an actual well established right at the time of adoption.

I don't claim to be an expert on the history, but I think if you're going to claim that the 9th protects a right not to be held in custody before trial and conviction, you need to knead a few historical facts into your dough. For myself, I'm struggling to see how the writ of habeas corpus could have developed in English Law, if it was commonly understood that the authorities could not hold accused persons pre trial.

“if you’re going to claim that the 9th protects a right not to be held in custody before trial”

Let me know when you find someone who believes that, and I’ll refute them for you.

I found three Founding Era state constitutions with the right to bail on noncapital cases, and that doesn’t count the states where this was the practice but it wasn’t specifically mentioned in their constitution.

Up to 1984 the feds recognized a right to bail in noncapital cases. Was this simply a matter of grace, or were they following the Constitution?

Here we go – Judiciary Act of 1789, NW Ordinance of 1787, the constitutions of all but two states admitted to the Union after 1789, plus the constitutions of North Carolina and Pennsylvania – seems like as close as one gets in the real world to a consensus about the right to bail in noncapital cases.

Donald B. Verrilli, Jr.,”The Eighth Amendment and the Right to Bail: Historical Perspectives,” Columbia Law Review, Vol. 82, No. 2 (Mar., 1982), pp. 328-362, at 351-54.

(Verilli calls this a developing, “nascent” right, which seems too modest a claim. The existence of a nigh-unanimous consensus after 1789 shows what the people believed their rights to be and therefore what they meant by retained rights in the 9A and privileges and Immunities in the 14A. Also, Verilli focuses on the 8th Amendment, which is OK, I guess, if you’re into that sort of thing)

It took out modern, enlightened era to deny the right to bail in noncapital cases.

Right. And remember, substantive due process protects deeply rooted traditions.

Why do the evil ministers fail to implement the Czar’s benevolent decrees?

These reformers don’t want to criticize the law itself (BRA) presumably because it would interfere with their “abolish cash bail” fetish and restoring the pre-BRA world would mean cash bail would be available in all noncapital cases.

No, they want to reserve the right to detain people pretrial, without bail, in some cases (“just the tip!”), but they are shocked (shocked!) that judges would run with this and deny bail in even more cases than they’re “supposed” to.

But if you’re a judge, and you have the power to deny bail to someone because they might commit a crime while out on bail, what are you going to do? Release the guy and end up reading accusatory media headlines about the crimes he committed after release? Or take the less risky course and just lock the guy up, just to be sure?

The countervailing pressure, I suppose, would be to release more defendants pretrial because of perverse conceptions of "racial justice," without any bail at all, while detaining a minority of political defendants without bail. A two-tiered system which basically grants or denies bail based on the social rank of the people who would be placed at risk. Turn loose those who would only prey on the poor and middle class, lock up those who threaten the interests of the wealthy.

One point Matthew Yglesias likes to make is that the tic in activism and academia that one must constantly talk about the racial impacts of everything is often counterproductive to reform. I.e., if you pitch an argument as benefitting everyone, it tends to get broader support than if you pitch it as an issue of racial justice.

But the incentives in academia, where Siegler and Lessnick work, are obviously towards overemphasizing racial angles, so this is how they wrote the paper.

Exactly. I kept making this point with regards to abortion: progressives couldn't help themselves; they had to keep talking about how overturning Roe would have a disproportionate impact on ______ group. (And of course they're so mindless on that subject that they threw LGBTQ in there, even though, obviously, a ban on abortion has a relatively small effect on gays and lesbians.) But if you go around telling white middle-class women, "This isn't really your problem; this is a problem for poor women, and 'BIPOC' women," then what do you expect the reaction of white women will be?

I'm not saying, of course, that people should or do only care about things that impact them. I'm saying, of course, that people will always care significantly more about things that impact them.

We see the same problem with welfare. When progressives are trying to destigmatize it, they will argue that actually whites make up most welfare recipients. But when budget votes are being held, and the GOP is trying to slash welfare, the activists revert to calling it racist because it will disproportionately affect minorities. Even if that's mathematically true, why on earth do they think it's a good idea to remind people of that?

Back in the earlier days of AIDS, activists recognized this issue, and made as their pitch the notion that AIDS can affect anyone, and that just because it started in certain communities didn't mean it wasn't going to be a problem for non-IV-drug-using heterosexuals. It mostly wasn't true, but it nevertheless was the right strategy to build support.

It may or may not be counterproductive to reform, but it's certainly counterproductive to persuading readers that the writers assertions about the law (ie what it is and whether it is being applied correctly) is believable.

If everything you say about the law is marinated in considerations of what the law should be and what impact it has on this or that, then that drains confidence in your statement of the facts and your analysis of the meaning of the law.

I confess that my patience for this series withered rapidly. It had a strong flavor of Irina Manta. Three parts "should" to one part "is."

I think that's the point. Judges should be following what the law is. When the vast majority don't, then you'll get lots of should.

“Back in the earlier days of AIDS, activists recognized this issue, and made as their pitch the notion that AIDS can affect anyone, and that just because it started in certain communities didn’t mean it wasn’t going to be a problem for non-IV-drug-using heterosexuals. It mostly wasn’t true, but it nevertheless was the right strategy to build support.”

I read an article with a different spin – that the specific association of AIDS and gay people actually made Americans *more* sympathetic to gays. Americans tend to sympathize with the sick and dying, and most were actually disgusted by the fringe who rejoiced in gay people suffering. If Americans were actually as hate-filled as the myths say, they would have been toasting each other over bad things happening to sexually-active gay people.

Sadly, the take-home lesson of the elite is not to criticize unhealthy behavior to avoid "stigmatizing" people - and the next frontier seems to be the "fat pride" movement.