The Volokh Conspiracy

Mostly law professors | Sometimes contrarian | Often libertarian | Always independent

Freedom Denied Part 3: Judges Must Stop Unlawfully Jailing Poor People Without Lawyers at the Initial Appearance Hearing

In Part II of our series describing the culture of detention that pervades the federal pretrial system, we explained how our Federal Criminal Justice Clinic's new report, Freedom Denied, found that judges and lawyers frequently misapply the Bail Reform Act's standard for detention at the Initial Appearance—often resulting in illegal jailing.

This post addresses the second of our four findings and recommendations: "Judges must stop unlawfully jailing poor people without lawyers at the Initial Appearance hearing."

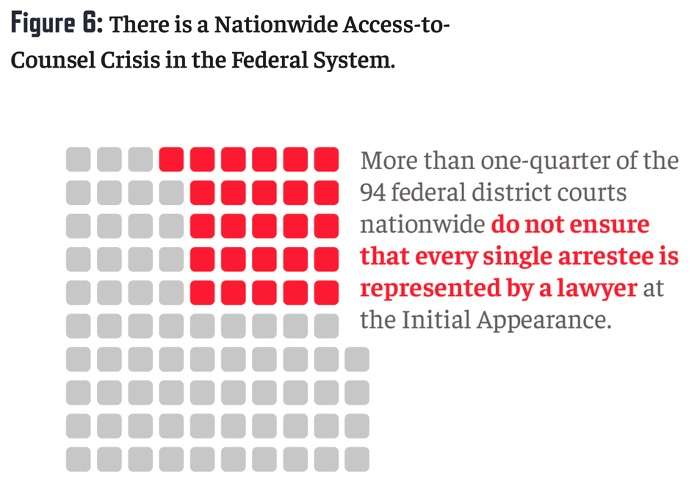

We were the first to uncover a serious and previously unexplored "access-to-counsel crisis" in the federal system. In more than a quarter of federal district courts across the country, an indigent individual can be jailed without a lawyer by their side:

In many federal courts, judges lock poor people in jail without a lawyer during their Initial Appearance, in violation of federal law. Our study uncovered a national access-to-counsel crisis: judges in more than one-quarter of the 94 federal district courts do not provide every arrestee with a lawyer to represent them during the Initial Appearance. See Figure 6. In fact, 72% of the districts where we interviewed or surveyed stakeholders deprive at least some individuals of counsel at this first bail hearing. While the scope of the problem varies across districts and divisions, in every court that exemplifies this particular crisis, arrestees are jailed without counsel. These widespread deprivations of counsel contribute to the culture of detention and drive high jailing rates at Initial Appearances nationwide….

Additionally, in interviews with and surveys of stakeholders, we learned that in at least 26 federal districts, judges fail to ensure that arrestees are represented by counsel at the Initial Appearance in some—and often many—cases. In certain courts, 100% of arrestees are deprived of counsel during their Initial Appearance. Our findings surely understate the scope of this particular crisis, as we were unable to interview stakeholders in 58 federal districts (62% of the total districts).

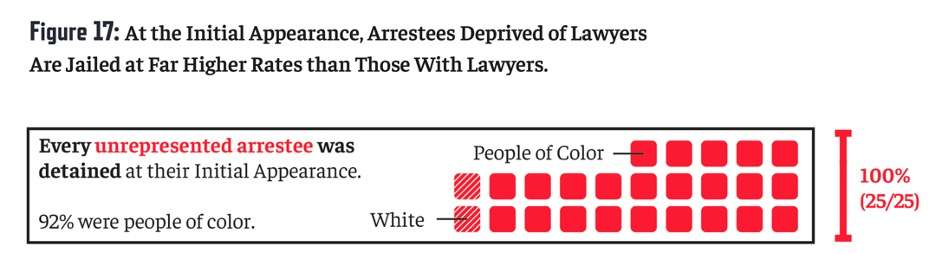

Indigent people who went unrepresented were locked in jail 100% of the time in our study; 92% were people of color:

Our data show that these legal failures come with serious consequences. Every uncounseled Initial Appearance we observed ended in pretrial detention—a far higher detention rate than at the Initial Appearances where arrestees were represented by counsel. See Figure 17. And nearly every single arrestee we observed who faced an Initial Appearance without a lawyer was either Black or Latino, exacerbating the already pronounced racial disparities in the criminal system. See id. These findings are particularly troubling given that most people charged with a federal crime do not have the money to hire their own lawyer and therefore rely wholly upon judges to appoint counsel at their Initial Appearances.

A judge who does not ensure that every single individual who appears before them is represented by counsel at the Initial Appearance violates a number of federal laws.

First, forcing someone to appear without counsel violates 18 U.S.C. § 3006A:

Section 3006A states in mandatory terms that every indigent arrestee "shall be represented … from initial appearance." The plain text of this law requires several things. First, it mandates "represent[ation]"—meaning a lawyer must actively appear on behalf of every arrestee and represent them as counsel, not just passively standby in an advisory capacity. Second, the plain language of the statute requires that each person be represented during their Initial Appearance. Dictionary definitions and case law define the word "from" inclusively, as a "starting-point" for a series. It follows that requiring representation "from initial appearance" does not mean a judge can provide counsel toward the end of that hearing, let alone after that hearing concludes. Rather, the law requires judges to provide each arrestee with a lawyer to stand up on their behalf and represent them for the entire duration of the Initial Appearance hearing.

Second, failing to provide counsel violates the Federal Rules of Criminal Procedure:

The Federal Rules of Criminal Procedure likewise require judges to provide counsel to represent every arrestee during the Initial Appearance. The text of Rule 44, which governs appointment of counsel, states that any arrestee unable to retain counsel shall have an attorney appointed to "represent the defendant at every stage of the proceeding from initial appearance through appeal." In its notes on the 1966 amendment to Rule 44, the Advisory Committee explained, "The phrase 'from his initial appearance before the commissioner or court' is intended to require the assignment of counsel as promptly as possible after it appears that the defendant is unable to obtain counsel." Rule 5, which discusses Initial Appearances specifically, also states that "[t]he judge must allow the defendant reasonable opportunity to consult with counsel" during the Initial Appearance hearing itself. Much like the CJA, these rules establish that every arrestee has the right to be actively represented by a lawyer for the entire duration of the Initial Appearance.

Third, the only way someone can meaningfully navigate the complexities of the BRA's legal standards is through counsel:

Beyond the laws requiring representation by counsel, every arrestee needs a lawyer to enforce the complex legal standard that applies at the Initial Appearance, ensure that the judge does not hold an unwarranted Detention Hearing, and prevent the person from being locked in jail in violation of the BRA. Every federal Initial Appearance involves a determination of detention or release governed by the BRA. When the prosecution moves for detention at the Initial Appearance, § 3142(f) sets forth the only lawful bases for detention and the holding of a Detention Hearing; courts are required to release the arrestee when no § 3142(f) factor is present. Unrepresented arrestees cannot effectively enforce their own rights under that statute, make their own bond arguments, or hold prosecutors and judges to the law's strictures.

Fourth, there is also a serious question as to whether the absence of counsel at the Initial Appearance violates the Constitution:

The federal Initial Appearance is a critical stage[, thus requiring appointment of counsel]. All available evidence illustrates that the outcome of the Initial Appearance may adversely affect an arrestee's rights, and that counsel is necessary to protect those rights under the BRA and navigate the pretrial labyrinth. The attachment rule is supposed to ensure that a person has a right to counsel at the point when "the accused 'finds himself faced with the prosecutorial forces of organized society, and immersed in the intricacies of substantive and procedural criminal law'"—such as the intricacies of the legal standard that applies during the federal Initial Appearance.

"The Solution: At the Initial Appearance, Judges Must Follow the Law and Appoint Lawyers to Actively Represent Every Indigent Arrestee."

The responsibility for this access-to-counsel crisis falls squarely on the judges' shoulders…. Every time a federal judge fails to provide a lawyer for an arrestee during the Initial Appearance and forces that person to appear pro se across from a prosecutor, they violate the law. Locking people in jail without lawyers is a perversion of the adversarial system.

Courts must ensure that every person accused of a federal crime is actively represented by a lawyer from the start of their Initial Appearance, and at least before any detention or release determination is made….

The best practice is to have a duty federal defender or CJA lawyer actively represent arrestees at every Initial Appearance, and for judges to secure additional CJA lawyers whenever the federal defender's office is conflicted out.

Prosecutors, too, have the responsibility and the power to address this access-to-counsel crisis:

Federal prosecutors should never participate in any hearing in a criminal case when there is no advocate on the other side. Instead, there should be a blanket DOJ policy requiring prosecutors to insist on the appointment of counsel at the Initial Appearance before any hearing is held—especially any hearing where they seek to jail the accused. If DOJ adopts such a policy, it is imperative that judges and other stakeholders hammer out the logistics so that counsel is provided promptly and the Initial Appearance is not delayed to procure counsel.

In fact, the Department of Justice recently issued internal guidance to Assistant United States Attorneys aimed at rectifying this access-to-counsel problem: "[P]art of the deputy attorney general's guidance on best practices for prosecutors [regarding pretrial detention] included an explicit reminder that federal law states that 'a defendant who is unable to obtain counsel is entitled to have counsel appointed to represent the defendant at every stage of the proceeding [including] initial appearance,' except where 'the defendant waives this right.'"

Finally, the Judicial Conference of the United States should take action to address this deprivation-of-counsel crisis by, at a minimum, releasing a policy statement reaffirming that federal law requires representation by counsel during every Initial Appearance hearing. The Judicial Conference's Guide to Judiciary Policy already makes clear that counsel must be appointed to represent indigent defendants at the Initial Appearance hearing before the government requests pretrial detention, but judges are not following this guidance. It is incumbent on the Judicial Conference to remind judges of their responsibility to provide appointed counsel at the beginning of the Initial Appearance hearing for every person charged in a federal criminal case.

Anything short of complete representation falls short of what the law requires and tramples on the liberty interests of people who have yet to be tried or convicted.

All block-quoted material comes from the Clinic's Report: Alison Siegler, Freedom Denied: How the Culture of Detention Created a Federal Jailing Crisis (2022).

Editor's Note: We invite comments and request that they be civil and on-topic. We do not moderate or assume any responsibility for comments, which are owned by the readers who post them. Comments do not represent the views of Reason.com or Reason Foundation. We reserve the right to delete any comment for any reason at any time. Comments may only be edited within 5 minutes of posting. Report abuses.

Please to post comments

Instead of spending money on this "study", wouldn't you be better off putting those funds toward a dedicated attorney or two to actually raise these claims of illegality in court?

On what evidence?

Hitring a lawyer would help one person one time. But to change things systematically, through e.g. new legislation, a class-action suit, or attempting to educate judges as a group, you need to show that there’s a systematic problem.

And for that, you need a study.

Poor person is indicted for murder. Doesn't have lawyer present at indictment. Judge follows Seigler & Lessnick's advice and frees defendant on own recognizance. Defendant goes home and kills someone else - a witness to the first crime he is accused of committing.

The above is a good all-around result exactly how?

At least based on this post, I don't see that the recommendation is to release anyone if they can't arrange for a lawyer to be there. Rather, the recommendation is to make sure that the court does arrange to have a lawyer there:

Given that the guy you're responding to doesn't know the difference between indictment and arraignment, I'm not sure he's going to grasp this.

In any case, note how he assumes the defendant is guilty. Framing it as "What if you release a guilty person and he commits another crime?" is stacking the deck. Frame it as, "Poor person is charged with murder. He doesn't have a lawyer and so the magistrate automatically remands him, or sets bail he can't afford. He languishes in jail, unable to help assist in his defense. Eventually he pleads guilty because of the burden of incarceration. The real killer goes out and kills someone else because the government stopped looking since they assumed they had the right person. The above is a good all-around result exactly how?"

Yep. Thank you for this. Hardly anyone outside of criminal lawyers understands anything about pretrial detention.

Instead of responding in lawyerese Dave, try addressing the concept as a whole. How is justice served, as a whole, when the public is in danger?

Conservatives are big “law and order” advocates . . . unless insurrectionists are being held to account, or the defendant is Trump, or the Catholic Church is the criminal’s employer, or a white gun nut kills a black guy, or the governor some assholes plotted against is a Democrat, or the defendant is Michael Flynn, or an in-American kook like John Eastman is being investigated, or . . ..