The Volokh Conspiracy

Mostly law professors | Sometimes contrarian | Often libertarian | Always independent

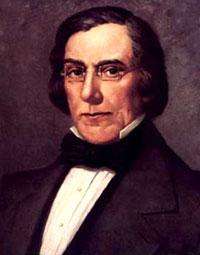

Today in Supreme Court History: January 10, 1842

1/10/1842: Justice Peter Daniel's takes the judicial oath.

Editor's Note: We invite comments and request that they be civil and on-topic. We do not moderate or assume any responsibility for comments, which are owned by the readers who post them. Comments do not represent the views of Reason.com or Reason Foundation. We reserve the right to delete any comment for any reason at any time. Comments may only be edited within 5 minutes of posting. Report abuses.

Please to post comments

Justice Peter Daniel's what?

Good question since his name was Daniel not Daniels.

"(Justice Peter Daniel) also joined the majority in Jones v. Van Zandt (1847) and wrote another concurrent opinion a decade later in Dred Scott v. Sandford (1857), to state that, 'the African negro race never have been acknowledged as belonging to the family of nations.'" (wiki)

I guess we can say he was a man of his times.

Too bad some people are still living in the 19th century.

You forgot to add that he owned slaves and participated in a duel.

Nope, didn't forget.

Just trying to avoid TL;DR.

who didn't in the early 19th century?

Also of interest is that he was nominated by outgoing President Martin Van Buren on February 26, 1841 (one week before William Henry Harrison was due to take office) and confirmed by the Senate four days later on March 2, 1841, two days before Harrison became President. However, for some reason he did not begin his service with the Court until Jan. 1842.

United States v. Georgia, 546 U.S. 151 (decided January 10, 2006): protections of ADA extend to those in state prison (prisoner could not get proper medical care or proper mobility because of lack of ramps, space to move his wheelchair, or accessible toilets)

United States v. Philbrick, 120 U.S. 52 (decided January 10, 1887): navy carpenter entitled to discretionary living allowances; 1835 statute prohibiting such allowances (and setting a fixed schedule) had been repealed in 1866 without any replacement language, so prior practice was permitted

Owens v. Okure, 488 U.S. 235 (decided January 10, 1989): §1983 claim (beaten by police) subject to state's residual 3-year statute of limitations as opposed to state's 1-year statute for intentional torts such as assault

Gonzalez v. Thaler, 565 U.S. 134 (decided January 10, 2012): appeal of conviction under Antiterrorism and Effective Death Penalty Act of 1996 did not require certificate as to which Constitutional violations are alleged; one-year habeas statute of limitations began to run when deadline for seeking cert. in highest state court expired (contention on habeas was that 10-year delay between indictment and trial violated Sixth Amendment speedy trial requirement; Court holds that habeas is time-barred, which is ironic)

Goldberg v. Sweet, 488 U.S. 252 (decided January 10, 1989): Illinois tax on calls only from or to in-state addresses did not violate Dormant Commerce Clause (in effect overruled by Comptroller of Treasury of Maryland v. Wynne, 2015, and by the march of technology)

In Goldberg v. Sweet Stevens observed that the effective tax rate was comparable for intra- and interstate calls. The result is like having both a sales tax and a use tax, each of which in isolation is discriminatory but in combination are complementary.

The "march of technology" also put an end to the so-called Spanish-American War telephone tax. Over a century ago Congress taxed telephone calls that were billed based on distance. Back then interstate wires were expensive and you paid more for calls to farther away. In recent decades calls started to be billed at a flat rate, if at all, avoiding the tax on linguistic grounds rather than moral grounds. The moral argument was, if this tax was a temporary measure to win the war with Spain why couldn't it be repealed? In fact it had been repealed and reenacted several times over the decades.

Thanks! Interesting.

Back then interstate wires were expensive and you paid more for calls to farther away. In recent decades calls started to be billed at a flat rate, if at all, avoiding the tax on linguistic grounds rather than moral grounds.

"Back then" was not so long ago. Long distance calls were billed on distance and time well into the 1980's (and 90's?). Once costs got down to about a nickel a minute it became counterproductive to track and bill individual calls.

I don’t recall distance-based billing in the 90s, but time-based certainly lived into the late 90s in urban/suburban areas, I would assume longer in rural areas.

Re: United States v. Georgia

Facts of the case

(Tony) Goodman, a paraplegic held in a Georgia state prison, sued Georgia in federal court for maintaining prison conditions that allegedly discriminated against disabled people and violated Title II of the Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA). Georgia claimed the 11th Amendment provided the state immunity from such suits. The district court ruled for Georgia, but the 11th Circuit reversed.

Before the 11th Circuit ruled in the case, the United States sued Georgia, arguing that the ADA's Title II abolished state sovereign immunity from monetary suits. Congress could do this, the U.S. argued, by exercising its 14th Amendment power to enforce equal protection.

Question

Did Title II of the Americans with Disabilities Act of 1990 validly abrogate state sovereign immunity for suits by prisoners with disabilities challenging discrimination by state prisons? Was Title II a proper exercise of Congress's power under Section 5 of the Fourteenth Amendment, as applied to the administration of prison systems?

Conclusion (Unanimous!)

Yes and yes. In a unanimous decision authored by Justice Antonin Scalia, the Court ruled that Title II abrogates sovereign immunity in cases where violations of the 8th Amendment are alleged. The 14th Amendment incorporates the 8th Amendment (that is, applies it to the states). Congress can enforce the 14th Amendment against the states "by creating private remedies against the States for actual violations" of its provisions, which can involve abrogating state sovereign immunity. However, the Court did not address the question of whether Title II validly abrogates sovereign immunity when the 8th Amendment is not involved. (oyez)

Thanks!

This was interesting!

My dumb question: If this case codified the incorporation of the 8th amendment by the 14th, does that imply that Congress could do away with the 8th amendment simply by saying that prisoners do not get equal protection in the legal system while adjudicating death penalty cases? It cannot be that easy, right?

I would think not. Congress can likely remove the private remedies, but I believe suing in federal court would remain an option. To do away with the 8th amendment thusly would require a constitutional amendment to create an exception for death penalty cases, or for SCOTUS to overturn its decision as it applies to such cases.

This is just an off the top of my head response without knowing a lot of the details of US v. Georgia, just applying general constitutional law as I understand it.

In 1836, Peter Daniel was appointed a district judge for the Eastern District of Virginia by President Andrew Jackson upon the recommendation of former President James Madison. Daniel succeeded Philip Barbour, whom Jackson had elevated to the Supreme Court. In 1840, while still a district judge, Daniel chaired the Virginia State Democratic Convention that nominated his good friend Martin Van Buren, the incumbent vice president, as the party's presidential candidate. Van Buren would win the 1840 presidential election, the last sitting vice president to do so until George H.W. Bush in 1988.

Van Buren would lose his 1844 re-election bid to Whig candidate William Henry Harrison. The Whigs also increased their majority in the House and captured the majority in the Senate, but, as it was in those days, the new President and Congress would not take office until March 4, 1841. On February 21, Supreme Court Justice Philip Barbour, the same man Daniel had succeeded as a district judge, died. On February 27, Van Buren nominated Daniel to the Court, and the Democratic Senate confirmed him on March 2, two days before the new Whig president and Senate took office.

Daniel was the last of the old-school Jeffersonians. He believed in a federal government of very limited powers and state governments of very expansive powers. His views were out of step and reactionary, even by the standards of the Taney Court. Of the 74 opinions he authored, 50 were dissents. He was a fierce defender of slavery, and an opponent of the federal government's ability to regulate it. His concurrence in Dred Scott made Chief Justice Taney's majority opinion look almost tame in comparison.

As his jurisprudence was out of date, even for his time, he left little enduring legal legacy, with one notable exception, his majority opinion in West River Bridge Co. v. Dix, 47 U.S. (6 How.) 507 (1848). In 1795, the State of Vermont had granted a charter to the company, allowing it to build a bridge over the West River and to collect tolls for 100 years. However, in an 1839 statute, the state converted the bridge to a free, public highway and gave the company $4000 in compensation for the taking. The company sued, claiming this was an impairment on the obligation of a contract, in violation of the Contracts Clause of the Constitution. (Daniel Webster represented the company and argued the case before the Court).

The Court sided with the state. While acknowledging that the charter was a contract, a state's power of eminent domain was an inherent governmental power, essential to sovereignty, and was not limited by the Contracts Clause:

Id.at 532-33.

Damn it! Sorry, I got my dates mixed up. Van Buren won the 1836 election and lost his re-election bid 1840.

Do you know if the $4000 compensation was based on the value of the bridge or the value of the contract? I would assume the 5th amendment would require the latter but that seems low for 56 years worth of tolls, even in the 19th century.

It seems the state commissioners deemed $4000 "full compensation for all real estate, easement, or franchise belonging to said corporation", and the Vermont Supreme Court accepted that.

This was, of course, before the Fourteenth Amendment (1868) and the incorporation of the Takings Clause against the states (1898), so the Fifth Amendment only applied to the federal government at the time. The determination of the amount of compensation would therefore have been wholly a state issue, unreviewable by the Supreme Court.

"On February 21, Supreme Court Justice Philip Barbour, the same man Daniel had succeeded as a district judge, died. On February 27, Van Buren nominated Daniel to the Court, and the Democratic Senate confirmed him on March 2, two days before the new Whig president and Senate took office."

I was assured that nominating Amy before the election was a break with precedent! Weird how that was wrong.

Well, especially since Daniel was nominated after Van Buren had lost the election and only a week before his term would expire and a new president was to be sworn in.

It was a break with the Garland precedent, you sad person.