The Volokh Conspiracy

Mostly law professors | Sometimes contrarian | Often libertarian | Always independent

Freedom Denied Part 2: Judges Must Follow the Correct Legal Standard at the Initial Appearance,

and stop jailing people unlawfully.

In our Federal Criminal Justice Clinic's new report, Freedom Denied, we sought to understand the current federal pretrial detention crisis that results in the pretrial jailing of three out of every four federal arrestees.

This post addresses the first of our four findings and recommendations: "Judges must follow the correct legal standard at the Initial Appearance hearing and stop jailing people unlawfully."

The Bail Reform Act of 1984 (BRA) allows the prosecution to move for detention at the Initial Appearance in only a limited set of cases.

There is a widespread misperception that prosecutors are entitled to a Detention Hearing every time they request one. However, under the BRA, the prosecutor may move for detention at the Initial Appearance only if authorized by one of the factors in § 3142(f) (the "(f) factors"). The BRA says that "the judicial officer shall hold a [detention] hearing" only "in a case that involves" one of the 7 (f) factors. "If none of the § 3142(f) factors are satisfied, however, the [judge] is prohibited from holding a detention hearing or detaining the defendant pending trial." If no (f) factor applies, the arrestee must, as a matter of law, be released at the Initial Appearance. In this sense, § 3142(f) "serve[s] as a gatekeeper to [pretrial] detention."

The BRA's legal standard at the Initial Appearance was a central reason that the Court in United States v. Salerno upheld the constitutionality of the Act: "The Act operates only on individuals who have been arrested for a specific category of extremely serious offenses. 18 U.S.C. § 3142(f)."

It is therefore especially troubling that

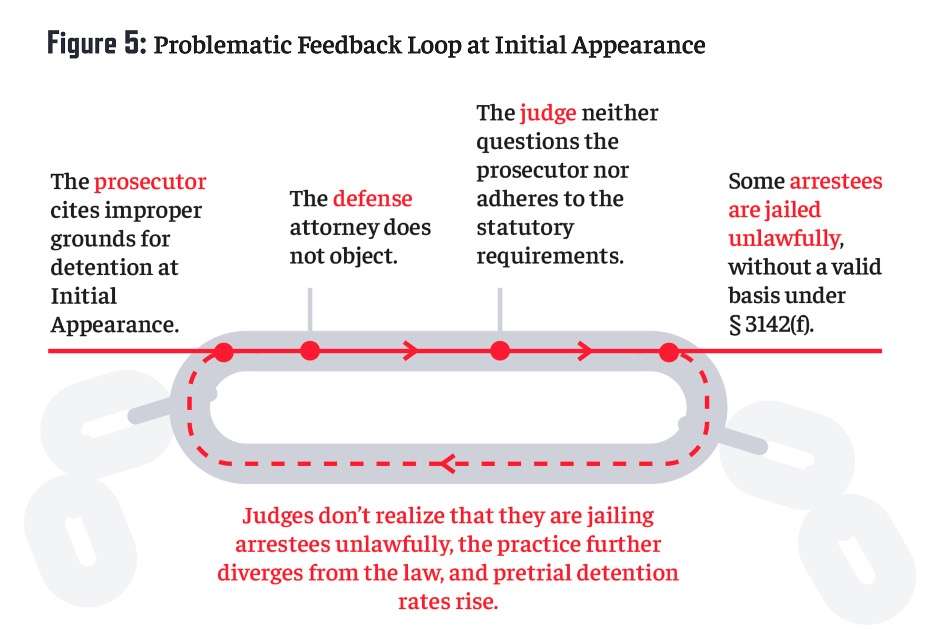

[o]ur data expose a severe misalignment between the BRA's prescribed Initial Appearance process and the practice that unfolds in federal courthouses around the country. We observed a problematic feedback loop play out during Initial Appearances: the prosecutor requests pretrial detention for reasons not authorized by the law, the defense attorney does not object, and the judge neither questions the prosecutor nor adheres to the statutory requirements, sometimes jailing people unlawfully. See Figure 5. When judges rubber stamp prosecutorial detention requests that deviate from the legal standard, prosecutors continue disregarding the law and judges continue jailing people improperly in a subset of cases—in an endless cycle. The illegal detentions that result from this mutually-reinforcing process ultimately lead to higher jailing rates at the Initial Appearance and beyond, and fall disproportionately on people of color.

We found that in some cases, judges illegally jail people who should be released back to the community:

Our most troubling finding was that, in 12% of Initial Appearances where the prosecutor was seeking detention, judges detained people illegally. See Figure 9. These were non-(f)(1) cases where, as a matter of law, there was no offense-specific ground for detention under § 3142(f)(1). In these non-(f)(1) cases, prosecutors did not cite or present evidence of any § 3142(f)(2) factor to support their detention request (the only possible statutory basis for detention). Instead, 97% of the time the prosecution cited improper grounds, like danger to the community or ordinary risk of flight.

Our other quantitative findings about the extent to which judges and lawyers misunderstand and misapply the BRA's legal standard are eye-opening:

In 81% of Initial Appearances in our study where the prosecutor requested detention, the prosecutor asked the judge to hold a Detention Hearing without citing any legal basis under § 3142(f). In some of these cases, prosecutors cited invalid bases for requesting a Detention Hearing, such as danger to the community or non-serious risk of flight. See Figure 9.

In over 99% of Initial Appearances where the prosecutor requested detention without citing a valid basis under § 3142(f), judges detained people without questioning prosecutors' grounds for detention. See Figure 9. This created a problematic feedback loop in which a prosecutor's request for detention at the Initial Appearance almost always resulted in a judicial order of detention, even when based on improper grounds. See Figure 5.

Our qualitative findings—gleaned through interviews with key stakeholders—corroborate this crisis:

Our interviews demonstrated that judges throughout the country mistakenly believe that prosecutors are entitled to a Detention Hearing whenever they request one—a position that disregards both the statute and well-established appellate case law. Most of the judges we interviewed either admitted to not knowing the legal rules that apply at the Initial Appearance or evinced a misunderstanding of the legal standards. More than half of the Chief Federal Defenders we interviewed likewise expressed confusion about the legal standard that applies at the Initial Appearance. Over and over, judges and attorneys alike were mystified when we began asking questions about the § 3142(f) requirements, and some expressed surprise at the basic idea that there is, in fact, a legal standard that applies during the Initial Appearance.

Our study revealed that unlawful jailing at the Initial Appearance falls disproportionately on people of color:

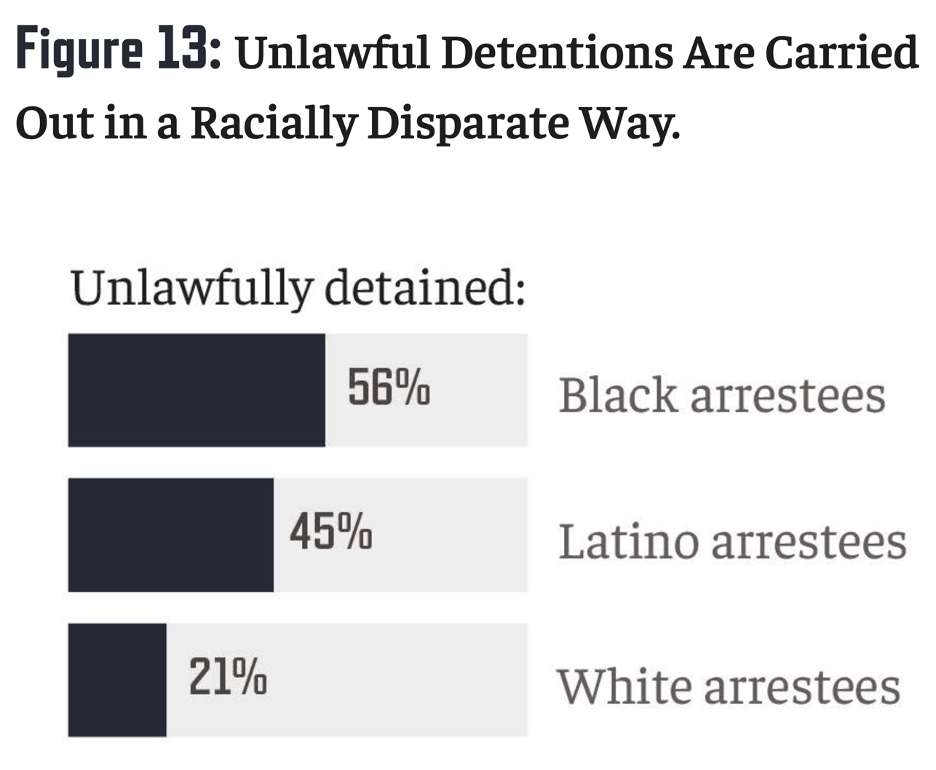

Moreover, these unlawful detentions were carried out in a racially disparate way. Among non-(f)(1) cases, 56% of Black arrestees and 45% of Latino arrestees were jailed on improper grounds at the Initial Appearance in non-(f)(1) cases, compared to just 21% of white arrestees.

Federal prosecutors contribute to these disparities:

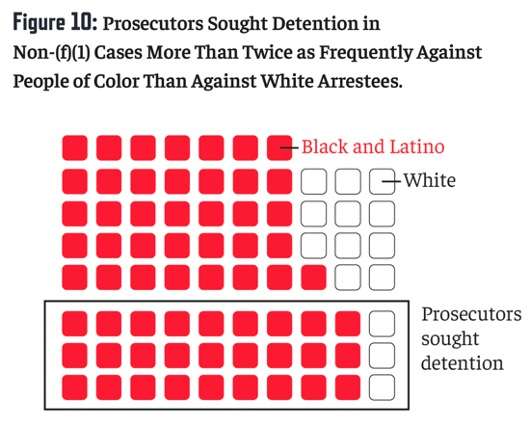

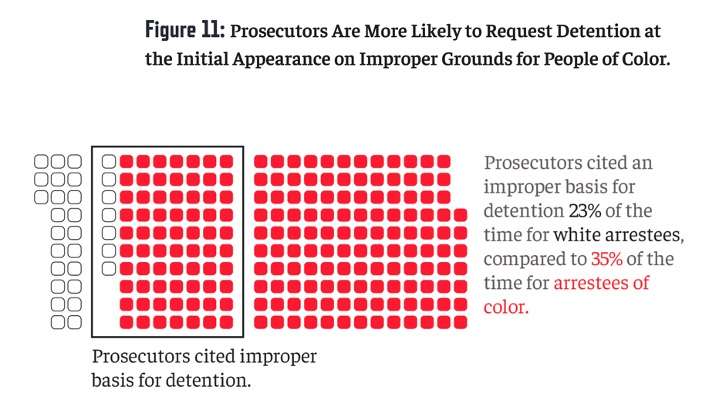

Prosecutors are more likely to request detention at the Initial Appearance for arrestees of color. In the non-(f)(1) cases we observed, the prosecution sought detention 43% of the time for people of color, but only 21% of the time for white arrestees. See Figure 10. Alarmingly, looking across all Initial Appearances, prosecutors cited an improper basis for detention 35% of the time for arrestees of color as compared to 23% of the time for white arrestees. See Figure 11. Arrestees of color are more likely to be illegally jailed at the Initial Appearance than their white counterparts.

"The Solution: At the Initial Appearance, Judges Must Prevent Unlawful Detentions by Following the § 3142(f) Legal Standard."

First, judges must understand the legal standard that applies during Initial Appearances and must recognize the strict limitations the BRA places on the types of cases in which a judge may hold a Detention Hearing or detain an arrestee at all….

Second, judges must be highly vigilant in ensuring that federal prosecutors comport with each element of the BRA's legal standard at the Initial Appearance. When a prosecutor requests detention and a Detention Hearing for reasons that Congress has deemed inappropriate or otherwise impermissible—like danger or ordinary flight risk—they are asking the judge to violate the law. Rather than rubber-stamping this improper invitation to detain, judges must be on guard, stand as the bulwark against illegal detention, and deny such requests….

Third, judges must be especially careful in the types of cases where we documented illegal detentions. These are non-(f)(1) cases where there is no offense-specific factor that authorizes a judge to hold a Detention Hearing, and where the only possible basis for detention is "serious risk" of flight or obstruction of justice under § 3142(f)(2)….

Fourth, judges can use their influence to mitigate the culture of detention [by ensuring that prosecutors' detention requests comport with the legal standard]….

By following these recommendations, judges can uphold the law, interrupt the culture of detention, and protect the liberty interests of the people who appear before them.

All block-quoted material comes from the Clinic's Report: Alison Siegler, Freedom Denied: How the Culture of Detention Created a Federal Jailing Crisis (2022).

Editor's Note: We invite comments and request that they be civil and on-topic. We do not moderate or assume any responsibility for comments, which are owned by the readers who post them. Comments do not represent the views of Reason.com or Reason Foundation. We reserve the right to delete any comment for any reason at any time. Comments may only be edited within 5 minutes of posting. Report abuses.

Please to post comments

Federal prosecutors and judges are a bunch of scoff-laws?

Say it ain't so!

I did not see anything in the article to indicate the prosecutors or judges are facing any kind of discipline over their illegal acts. Perhaps yet another useless House Committee hearing would help?

Discipline? On the rare case where a prosecutor's misconduct is called out by appellate courts, a bunch of prosecutors' organizations will throw a hissy fit of the judges so much as name the prosecutor.

It does appear from my experience that a memo has gone out to magistrate judges on this point within the last year. If that’s a result of your work, congratulations and thank you.

The report says that practitioners in Chicago noticed a change in people citing the correct standard after you pointed out that they weren’t. Have you noticed any corresponding change in detention rates? My intuition (and experience) is that the cases where the discussion of detention is cursory tend to be the ones where the case for detention is very strong—obviously it should still be done pursuant to the statute, but I wouldn’t necessarily think that that conformity would actually make a substantive difference.

Also, I noticed that the report has a lot of “figures” that are just illustrations of what a percentage is. Does anyone find that illuminating?

I'm curious whether the 12% (of arrestees detained where no legitimate reason existed) counts people who probably were flight or obstruction-of-justice risks, but the court just didn't make an explicit finding to that effect. 12% is at least 3% too high, per Blackstone's ratio, but it is much less worrying if the failure was a failure to document the reason rather than a failure to apply the right standard.

I think the figures are meant for use outside the work, for example as an eye-catching illustration on social media. For people who spend the time to read, I don't think the figures add any value.

Right, that's my point. Obviously it's not feasible for the people in the project to make that assessment at the time, but it would have been useful to note at least a random subset of cases and try to assess from the docket later on.

The admitted ignorance as to the law of both judges and defense attorneys is horrifying and unacceptable.

"gleaned through interviews with key stakeholders"

Anonymous interviews are the best kind of evidence!

Bob doesn't like polls, or interviews, or statistics. The only evidence he'll accept is what he hears on Tucker Carlson.

One can make up anything and say it is based on "interviews" with unnamed persons. How does one verify any of the claims? We don't even know who they allegedly talked to.

Most people don't operate in bad faith like you do, Bob.

Very interesting content, unusually libertarian.

Still no respect for Jaden Lessnick with respect to attribution.

He does have a bio if you click on his name:

Not sure why it's not included in the actual post.

Are we conflating several issues here?

Specifically, are all of these detentions without bail, or does it include defendants who would not or would not post bail? Are all of the Sec. 3142(f) hearings seeking pre-trial detention without bail, or is that being used as a shorthand for a conventional bail hearing where the judge/magistrate decides the conditions of release?

Sec 3142 is a little vague on the process to be used to make the findings necessary under (b) or (c). Sub (f) is the only provision that actually talks about a hearing.

Subsections (e) and (f) are required for a detention order (i.e. an order that someone cannot be released under any circumstances). Setting release conditions (including requiring bail to be posted) is permitted in any case.

Burn the BRA.

Enough of this good-czar-bad-ministers nonsense.

If the judges can’t handle their detention power responsibly, take that power away from them. Assuming for the sake of argument that there’s a responsible way to deny bail in a noncapital case.

And it's time to reconsider this abolish-cash-bail nonsense, since we're seeing what it could lead to: (a) a regime which presumes in favor of detention without bail, or (b) a regime where political prisoners are detained pretrial while regular hoodlums are simply turned loose on the community without bail.

” the defense attorney does not object”

In my mind this constitutes a waiver of the BLA rules, of sorts. Of course, why don’t defense attorneys object? Because they are incompetent, because they don’t know the law, or for other reasons**?

If judges are unaware of the law, I partly blame the defense attorneys who are not objecting in the first place.

**For example, perhaps because they expect a conviction or plea bargain, and tell the client “may as well get your sentence started now” ??

I am thinking to have an appealable case the defense has to a) object and preserve the issue for appeal; b) have a client wrongfully prosecuted or found not guilty. I am thinking people who are eventually convicted or plead do not appeal wrongful detention.

IME with folks looking at prison time, even when it comes as a result of a plea bargain, it is quite useful to have time to get their affairs in order. I can't think of many folks who would seriously consider "might as well get it started now" to be good advice.

Not saying it's impossible, but there's not much (if any) advantage to starting the clock at the time of arrest, and there are good reasons to have a scheduled surrender date.

I haven't looked into it, but I'd think a BRA violation is quickly appealable and doesn't turn on b) - if the appeal occurs before conviction and sentencing, when a person can still be released. You may be right that there aren't appeals after sentencing, as there's not much of a remedy at that point. But that doesn't preclude immediate appeal if the trial hasn't happened yet.

"I’d think a BRA violation is quickly appealable" -> maybe. But the defense attorneys are not objecting in the first place. Which makes me wonder.

That is correct, a magistrate's detention order is immediately appealable to the district judge, and if the district judge continues detention you have the right to an interlocutory appeal with the circuit court.

In my experience, it's either because it's obvious that the person is going to be detained, or because it's obvious that any viable release plan is going to take time to arrange.

Ugh, the graphic design & layout of the full report is a crime in itself.

Maybe it looks better in dead-tree format, but I'm skeptical.

This article got off to a good start explaining the requirement to assess the detention hearing against the 7 factors from § 3142(f). Unfortunately, rather than teaching what those factors are, the article then rambled back into the same "it's horrible" statistics with inferences (but not actual evidence) of racism.

Since I had to look them up myself, here's my synopsis. Detention hearings may be requested for cases involving:

1. a crime of violence (a pretty broad term) or certain other offenses carrying a maximum penalty of 10 yrs

2. any office with a maximum penalty of life or death

3. a different subset of offenses carrying a maximum penalty of 10 yrs

4. any felony if it's your third strike

5. any felony that involves a minor victim, use of a firearm or a couple other caveats

6. a serious risk that the person will flee

7. a serious risk that the person will obstruct or attempt to obstruct justice (such as by threatening a witness)

Taken in total, I am a lot less convinced by the analysis above. The definitions in that list of 7 are so broad that almost any case could be shoehorned into it. I wouldn't be surprised to hear that prosecutors were too lazy to cite their reasons 99% of the time but the implication of the article was that they couldn't cite a valid reason 99% of the time. That seems a lot less likely now.

I think they want to pretend the problem is with the implementation of the law, not with the law itself.

I share your frustration that the article did not discuss the “(f) factors” more in-depth but I wanted to clarify a few things about the factors.

1. The first (f) factor is the “crime of violence,” sex trafficking and terrorism crimes. You’re certainly correct that “crime of violence” is defined broadly. So broad, in fact, that the Supreme Court has found the definition’s residual clause to be unconstitutionally vague in similar worded statutes elsewhere in the United States Code. But even without the residual clause, I think you’re right to say that “crime of violence” def’n gives the prosecution a lot of wiggle room to ask for a detention hearing for violent crimes.

2. The second (f) factor is the “life or death” offenses. Pretty self-explanatory. We’re talking about the most serious crimes.

3. The third (f) factor is limited to certain drug offenses involving “a maximum term of imprisonment of ten years or more.” Based on my cursory review, this would likely apply to most trafficking and manufacturing offenses but not simple possession (Please correct me if I’m wrong).

4. The fourth (f) factor is not “any felony if it’s your third strike.” Rather, it’s “any felony” if the defendant has a history of “offenses described in subparagraphs (A) through (C).” For instance, if the defendant is charged with felony mail fraud (an offense not covered by subparagraphs (A) through (C), the prosecution may request a detention hearing if the person has a history of violence, sex trafficking, terrorism, drug offenses, etc.

5. The fifth (f) factor is “any felony . . . that involves a minor victim,” “involves the possession or use of a firearm or destructive device, or any other dangerous weapon,” “or involves failure to register [as a sex offender].”

All in all, I’m not sure the (f) factors “are so broad” that they cover “almost any case.” For instance, it’s not apparent to me that any of the factors would typically apply to criminal cases involving fraud, theft, embezzlement, money laundering, and other financial crimes unless the defendant presented a “serious” flight or obstruction risk. Those types of cases accounted for roughly 10% of federal criminal cases in FY 2021. Anyway, just food for thought.

I'm still skeptical of publishing a "study" that claims to be scientific that's really just your opinion about the legality of a particular practice.

In reading through this, it seems to me that the "study" was very sloppily done. It seems to have involved sending law students to sit in federal court and take notes and the professor wrote an article based on those notes. Here is an example cited in the report as an erroneous "For example, during an Initial Appearance in a mail fraud case involving an indigent Black arrestee, the prosecutor cited legally erroneous bases for detention: “We seek pretrial detention based on risk of flight and danger to the community.”" The source cited is "Verbatim Notes Form of Initial Appearance." So, some law student was watching an Initial Appearance and filled out a form. These notes are obviously incomplete. Or there is more to them that they don't disclose in the report. In any event, 3142 (f)(2)(A) makes "a serious risk that such person will flee" grounds for filing a motion to detain. It is not necessary to say verbatim "a serious risk that [the defendant] will flee" to communicate to the judge and the other party that the basis for the motion is 3142 (f)(2)(A). The motion clearly did that. Given that "a serious risk that such person will flee" is not a defined term, it is really just the authors' opinion that the risk of flight was not serious in a given case. That doesn't make the detention illegal. The judge is within her prerogative to disagree. Danger to the community is specifically listed as a factor to consider under 3142 (g) when making the determination required under 3142 (e). Contrary to the statement in the report, there is nothing illegal about considering those factors in making the determination. In that instance, the detention hearing was scheduled 5 days later and the judge issued a detention order. It's interesting to note that there is no argument in the report regarding the sufficiency of the evidence presented at that hearing. The sole argument is that there was no basis to hold the hearing in the first place, except that there was a basis cited under 3142 (f)(2)(A). This is just one example in which it is clear solely from the authors' own report that their conclusion that it was illegal to hold a detention hearing in that case is erroneous. If this is the prime example that the authors are going to highlight, I really question their conclusions and the quality of their "study."