Freedom Denied Part 2: Judges Must Follow the Correct Legal Standard at the Initial Appearance,

and stop jailing people unlawfully.

In our Federal Criminal Justice Clinic's new report, Freedom Denied, we sought to understand the current federal pretrial detention crisis that results in the pretrial jailing of three out of every four federal arrestees.

This post addresses the first of our four findings and recommendations: "Judges must follow the correct legal standard at the Initial Appearance hearing and stop jailing people unlawfully."

The Bail Reform Act of 1984 (BRA) allows the prosecution to move for detention at the Initial Appearance in only a limited set of cases.

There is a widespread misperception that prosecutors are entitled to a Detention Hearing every time they request one. However, under the BRA, the prosecutor may move for detention at the Initial Appearance only if authorized by one of the factors in § 3142(f) (the "(f) factors"). The BRA says that "the judicial officer shall hold a [detention] hearing" only "in a case that involves" one of the 7 (f) factors. "If none of the § 3142(f) factors are satisfied, however, the [judge] is prohibited from holding a detention hearing or detaining the defendant pending trial." If no (f) factor applies, the arrestee must, as a matter of law, be released at the Initial Appearance. In this sense, § 3142(f) "serve[s] as a gatekeeper to [pretrial] detention."

The BRA's legal standard at the Initial Appearance was a central reason that the Court in United States v. Salerno upheld the constitutionality of the Act: "The Act operates only on individuals who have been arrested for a specific category of extremely serious offenses. 18 U.S.C. § 3142(f)."

It is therefore especially troubling that

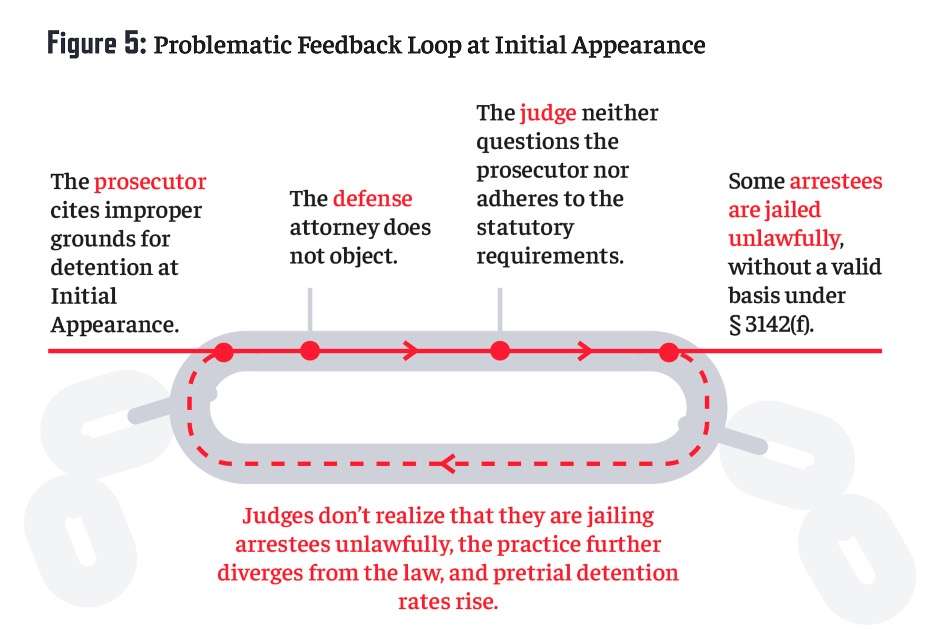

[o]ur data expose a severe misalignment between the BRA's prescribed Initial Appearance process and the practice that unfolds in federal courthouses around the country. We observed a problematic feedback loop play out during Initial Appearances: the prosecutor requests pretrial detention for reasons not authorized by the law, the defense attorney does not object, and the judge neither questions the prosecutor nor adheres to the statutory requirements, sometimes jailing people unlawfully. See Figure 5. When judges rubber stamp prosecutorial detention requests that deviate from the legal standard, prosecutors continue disregarding the law and judges continue jailing people improperly in a subset of cases—in an endless cycle. The illegal detentions that result from this mutually-reinforcing process ultimately lead to higher jailing rates at the Initial Appearance and beyond, and fall disproportionately on people of color.

We found that in some cases, judges illegally jail people who should be released back to the community:

Our most troubling finding was that, in 12% of Initial Appearances where the prosecutor was seeking detention, judges detained people illegally. See Figure 9. These were non-(f)(1) cases where, as a matter of law, there was no offense-specific ground for detention under § 3142(f)(1). In these non-(f)(1) cases, prosecutors did not cite or present evidence of any § 3142(f)(2) factor to support their detention request (the only possible statutory basis for detention). Instead, 97% of the time the prosecution cited improper grounds, like danger to the community or ordinary risk of flight.

Our other quantitative findings about the extent to which judges and lawyers misunderstand and misapply the BRA's legal standard are eye-opening:

In 81% of Initial Appearances in our study where the prosecutor requested detention, the prosecutor asked the judge to hold a Detention Hearing without citing any legal basis under § 3142(f). In some of these cases, prosecutors cited invalid bases for requesting a Detention Hearing, such as danger to the community or non-serious risk of flight. See Figure 9.

In over 99% of Initial Appearances where the prosecutor requested detention without citing a valid basis under § 3142(f), judges detained people without questioning prosecutors' grounds for detention. See Figure 9. This created a problematic feedback loop in which a prosecutor's request for detention at the Initial Appearance almost always resulted in a judicial order of detention, even when based on improper grounds. See Figure 5.

Our qualitative findings—gleaned through interviews with key stakeholders—corroborate this crisis:

Our interviews demonstrated that judges throughout the country mistakenly believe that prosecutors are entitled to a Detention Hearing whenever they request one—a position that disregards both the statute and well-established appellate case law. Most of the judges we interviewed either admitted to not knowing the legal rules that apply at the Initial Appearance or evinced a misunderstanding of the legal standards. More than half of the Chief Federal Defenders we interviewed likewise expressed confusion about the legal standard that applies at the Initial Appearance. Over and over, judges and attorneys alike were mystified when we began asking questions about the § 3142(f) requirements, and some expressed surprise at the basic idea that there is, in fact, a legal standard that applies during the Initial Appearance.

Our study revealed that unlawful jailing at the Initial Appearance falls disproportionately on people of color:

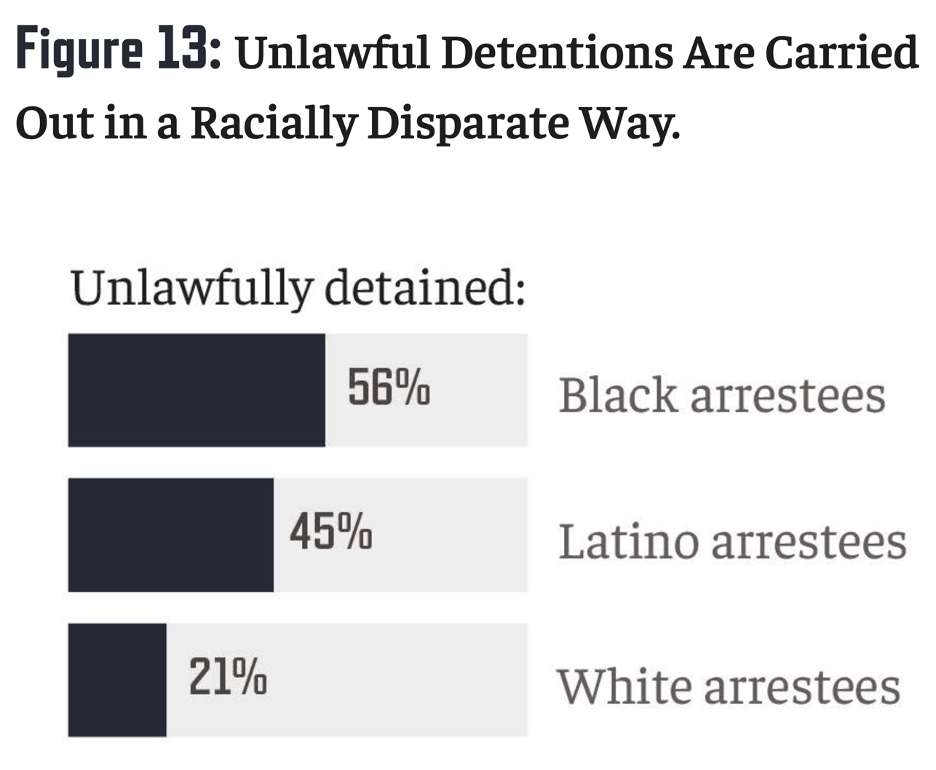

Moreover, these unlawful detentions were carried out in a racially disparate way. Among non-(f)(1) cases, 56% of Black arrestees and 45% of Latino arrestees were jailed on improper grounds at the Initial Appearance in non-(f)(1) cases, compared to just 21% of white arrestees.

Federal prosecutors contribute to these disparities:

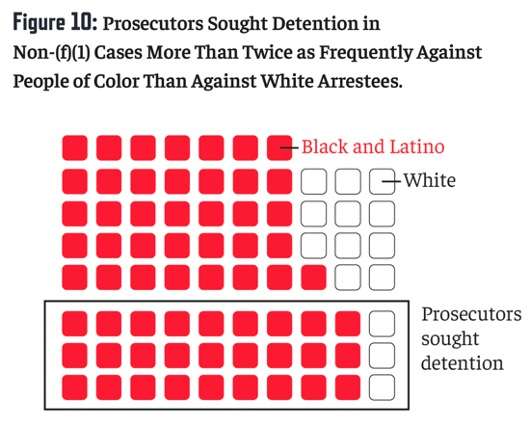

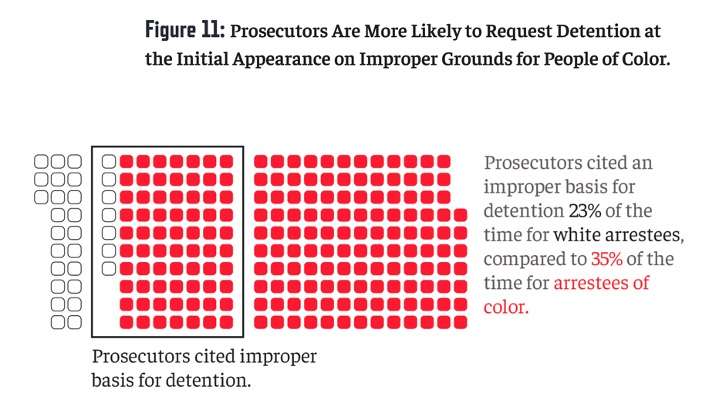

Prosecutors are more likely to request detention at the Initial Appearance for arrestees of color. In the non-(f)(1) cases we observed, the prosecution sought detention 43% of the time for people of color, but only 21% of the time for white arrestees. See Figure 10. Alarmingly, looking across all Initial Appearances, prosecutors cited an improper basis for detention 35% of the time for arrestees of color as compared to 23% of the time for white arrestees. See Figure 11. Arrestees of color are more likely to be illegally jailed at the Initial Appearance than their white counterparts.

"The Solution: At the Initial Appearance, Judges Must Prevent Unlawful Detentions by Following the § 3142(f) Legal Standard."

First, judges must understand the legal standard that applies during Initial Appearances and must recognize the strict limitations the BRA places on the types of cases in which a judge may hold a Detention Hearing or detain an arrestee at all….

Second, judges must be highly vigilant in ensuring that federal prosecutors comport with each element of the BRA's legal standard at the Initial Appearance. When a prosecutor requests detention and a Detention Hearing for reasons that Congress has deemed inappropriate or otherwise impermissible—like danger or ordinary flight risk—they are asking the judge to violate the law. Rather than rubber-stamping this improper invitation to detain, judges must be on guard, stand as the bulwark against illegal detention, and deny such requests….

Third, judges must be especially careful in the types of cases where we documented illegal detentions. These are non-(f)(1) cases where there is no offense-specific factor that authorizes a judge to hold a Detention Hearing, and where the only possible basis for detention is "serious risk" of flight or obstruction of justice under § 3142(f)(2)….

Fourth, judges can use their influence to mitigate the culture of detention [by ensuring that prosecutors' detention requests comport with the legal standard]….

By following these recommendations, judges can uphold the law, interrupt the culture of detention, and protect the liberty interests of the people who appear before them.

All block-quoted material comes from the Clinic's Report: Alison Siegler, Freedom Denied: How the Culture of Detention Created a Federal Jailing Crisis (2022).