The Volokh Conspiracy

Mostly law professors | Sometimes contrarian | Often libertarian | Always independent

Freedom Denied Part 1: How the Culture of Detention Created a Federal Jailing Crisis

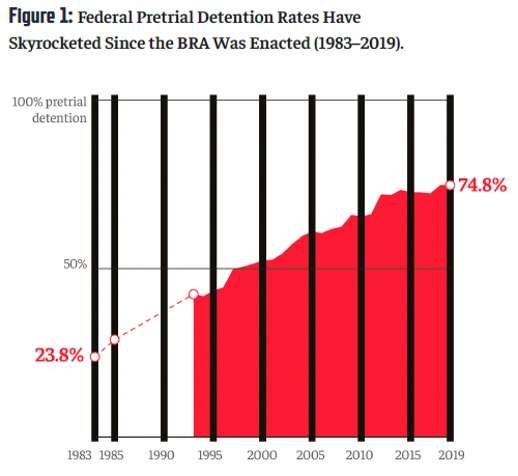

Our Federal Criminal Justice Clinic at the University of Chicago Law School recently released the first comprehensive national investigation of federal pretrial detention—Freedom Denied: How the Culture of Detention Created a Federal Jailing Crisis. We conducted this study to understand why the federal system jails 75% of those pending trial, even though they are presumed innocent and have not been tried or convicted. We discovered that federal judges routinely lock people in jail in violation of the law, which increases jailing rates and exacerbates racial disparities.

In 1987, the Supreme Court upheld the constitutionality of jailing federal defendants before trial in United States v. Salerno, declaring, "In our society, liberty is the norm, and detention prior to trial or without trial is the carefully limited exception." At that time, just 29% of people charged with federal crimes were jailed before trial; the rest were released back to their families. But today, pretrial jailing has become the norm, and we conclude that "the culture of detention" is to blame:

This Report reveals a fractured and freewheeling federal pretrial detention system that has strayed far from the norm of pretrial liberty. This Report is the first broad national investigation of federal pretrial detention, an often overlooked, yet highly consequential, stage of the federal criminal process. Our Clinic undertook an in-depth study of federal bond practices, in which courtwatchers gathered data from hundreds of pretrial hearings. Based on our empirical courtwatching data and interviews with nearly 50 stakeholders, we conclude that a "culture of detention" pervades the federal courts, with habit and courtroom custom overriding the written law. As one federal judge told us, "nobody's … looking at what's happening [in these pretrial hearings], where the Constitution is playing out day to day for people."

The culture of detention is so deeply engrained that it often overrides explicit protections and requirements codified in the Bail Reform Act:

Our primary explanation for the legal violations documented in this Report is the phenomenon we have labeled the culture of detention…. Even when the [statute] contains clear instructions, judges and prosecutors frequently ignore those instructions in favor of longstanding district practices, substituting courtroom habits for the plain text of the statute and overincarcerating people in the process…. [O]ne judge we interviewed justified those deviations by saying: "Oh, that's just the way we do it."

Media coverage of the report corroborates that these "systemic problems are largely the result of what judges and advocates [say] … is a poorly-written, war-on-drugs-era statute known as the Bail Reform Act of 1984, an over reliance on prosecutorial discretion, and risk-averse magistrate judges and federal defenders."

Our report identifies four distinct problems.

First, we found that federal magistrate judges misunderstand and misapply the Bail Reform Act's legal standard at Initial Appearance Hearings, the first bail hearing:

Our study found that there is a severe misalignment between the legal standard that applies during Initial Appearance hearings and the practice that unfolds in courthouses around the country. Judges routinely ignore the legal standard in § 3142(f) [of the Bail Reform Act] and sometimes jail people unlawfully….

Our most troubling finding was that, in 12% of Initial Appearances where the prosecutor was seeking detention, judges detained people illegally.

We also found disturbing racial disparities stemming from this problem:

Moreover, these unlawful detentions were carried out in a racially disparate way…. The unlawful detentions we observed are just the tip of the iceberg…. This is not just an isolated situation in which a few judges or attorneys slightly misunderstand the law; rather, there is a pervasive, systemic deprivation of liberty that is not authorized by statute or case law.

Second, although federal law requires judges to provide lawyers for everyone who appears in court, we documented "a national access-to-counsel crisis":

In many federal courts, judges lock poor people in jail without a lawyer during their Initial Appearance, in violation of federal law. Our study uncovered a national access-to-counsel crisis: judges in more than one-quarter of the 94 federal district courts do not provide every arrestee with a lawyer to represent them during the Initial Appearance….

Locking people in jail without counsel violates the U.S. Code and the Federal Rules of Criminal Procedure, may be unconstitutional, and is not sound public policy….

Unsurprisingly, our data show that detention rates at the Initial Appearance increase as representation decreases.

This access-to-counsel crisis falls disproportionately on people of color:

Black and Latino individuals were also more likely than white individuals to face the Initial Appearance without the full assistance of counsel. While just 13% of white arrestees were only partially represented at their Initial Appearance, over 30% of Black and Latino individuals faced the same problem—more than twice as many. Moreover, white arrestees received full representation in 80% of their Initial Appearances, while Black and Latino arrestees received full representation in 60% and 53% of their Initial Appearances, respectively.

Third, we learned that "[c]ourts misunderstand and misapply the [statutory] presumption of detention [that applies in most federal drug cases], further contributing to the culture of detention":

The statutory presumption of detention that applies to many federal offenses during the Detention Hearing is a primary driver of sky-high pretrial detention rates. The practice surrounding the presumption—and the presumption itself—contradict the sacred promise of "innocent until proven guilty" and reverse the BRA's "clear preference for pretrial release."

This misapplication of the presumption of detention falls most heavily on people of color:

The burden of the presumption of detention is not borne equally by all arrestees. Using sentencing data as a proxy, we estimate that most arrestees facing a presumption are people of color, since they make up 75% of those convicted of qualifying drug offenses nationwide. In this study, the proportion of people of color was even higher: 89% of presumption cases involved people of color, while only 11% involved white arrestees.

Fourth, we found that judges regularly disregard the Bail Reform Act's prohibition against jailing people who cannot afford to pay a monetary bail—also contributing to racial disparities:

Our courtwatching study shows that federal judges consistently impose financial conditions of release that result in pretrial detention. This practice violates the explicit statutory language of the Bail Reform Act, perpetuates a system where wealth buys release and people are jailed for poverty, and has a disproportionate racial impact. These detentions, which violate the law, contribute to rising detention rates as well as racial and socioeconomic disparities in the federal system.

Overall, we found that high federal jailing rates fall overwhelmingly on people of color and low-income individuals. In our study, people of color were significantly more likely to be illegally jailed at their Initial Appearance hearing, to be deprived of counsel at that hearing, and to be jailed unlawfully on financial conditions they could not meet.

This culture of pretrial detention inflicts severe and enduring damage on people and their communities:

Pretrial detention has myriad pernicious consequences, harming individuals, as well as their loved ones and communities. First, it prevents people from accessing necessary healthcare, subjects them to dangerously overcrowded living conditions, exposes them to physical violence, and increases their vulnerability to infectious diseases. Second, people who are jailed pending trial in the federal system are more likely to be convicted, sentenced to longer terms of incarceration, and sentenced pursuant to a mandatory minimum than their released peers. Finally, pretrial detainees experience employment and housing instability at a higher rate than their released peers, and they can lose custody of their children after even a few days in jail.

The crisis that our study identifies is extraordinarily serious, but it is not insurmountable. The simple solution is that judges must adhere more closely to the letter of the law. Our report provides recommendations for judges and attorneys alike to realign courtroom practices with the protections ensconced in the Bail Reform Act:

Fear may inform many of the harms we identify in this Report. It is incumbent upon judges to act boldly and to be guided by data, not institutional pressures…. We hope that our Report empowers federal judges to continue shifting the culture that has brought the federal system to this calamitous point…. Ultimately, federal judges have the power to uphold the rule of law, to make detention prior to trial the rare exception, and to be champions of liberty.

This is the first post of a five-part series. Later posts will take a closer look at each of the four problems and our recommendations. All block-quoted material comes from the Clinic's Report: Alison Siegler, Freedom Denied: How the Culture of Detention Created a Federal Jailing Crisis (2022).

Editor's Note: We invite comments and request that they be civil and on-topic. We do not moderate or assume any responsibility for comments, which are owned by the readers who post them. Comments do not represent the views of Reason.com or Reason Foundation. We reserve the right to delete any comment for any reason at any time. Comments may only be edited within 5 minutes of posting. Report abuses.

Please to post comments

Wow! That's pretty shocking stuff.

Who has standing to challenge it nationwide?

Can you interest a TV magazine show in this subject? That might accomplish more than 100 written articles published in obscure places.

Since the Bail Reform Act allows each defendant the opportunity to challege a detention order in their individual cases - including through an expedited interlocutory appeal with recourse to certiorari - it's hard for me to see how anyone would.

"Second, people who are jailed pending trial in the federal system are more likely to be convicted, sentenced to longer terms of incarceration, and sentenced pursuant to a mandatory minimum than their released peers. "

I'm wondering whether the report determines whether this is a causal relationship or just a correlation. It wouldn't surprise me if people against whom there is substantial evidence of guilt are both more likely to be jailed pretrial and more likely to receive more severe sentences.

It could easily be coincidental in a system with a 90+% conviction rate.

Defendants who are detained pending trial are less able to help their attorneys prepare for trial, which increases their chances of being convicted. My only major felony experience is that twenty years ago I represented a client who was accused of attempted murder. He was able to get bail, and his ability to help me track stuff witnesses and other information was invaluable in my case preparation. He was acquitted, and if not for his help with case prep I'm not at all certain that outcome would have been the same.

Detained people have more incentive to accept plea deals, which may be related.

This does seem like a clear issue: the factors (e.g. a history of serious criminal behavior, commission of a serious violent crime, likelihood of conviction and a lengthy sentence that make someone more likely to be detained also seem like factors that would make someone more likely to become one of the small percentage of lawbreakers who gets prosecuted federally.

I look forward to learning how Prof. Siegler and Mr. Lessnick untangle this.

Got a semi-unrelated question: what proportion of federal defendants are charged with "white collar" crimes, or non-violent crimes, or other crimes where repeat offenses while out on bail are not a danger to the community in the same way that murderers or carjackers or home burglars are, and how does this compare to state and local defendants?

I realize the War on (Some) Drugs is hard to ignore in this regard. I'm just curious as a general matter. 10%? 50%? 90%

That's actually an interesting question, with a more complicated answer. It's important to note that Federal Crimes tend to be far different in their breakdown when compared to state crimes.

The breakdown is in the US Sentencing Report Commission for 2021. But about 10% of crimes are classic "white collar" (Fraud, embezzlement, money laundering). ~30% of Federal Crimes are Immigration, where some may say there is a significant risk of not showing up to the hearing. Another ~30% are drug charges (typically manufacturing, trafficking, sales. A very minor % are possession). The last 20% is a mix (Firearms, child porn, sex assault).

What's interesting is 98% of defendants plead guilty.

https://www.ussc.gov/research/sourcebook-2021?utm_medium=email&utm_source=govdelivery

Thanks -- hadn't known immigration was so high, nor sexual assault.

What percentage of Immigration crimes are the Coyotes who smuggle them?

Law school clinics have too often been cesspools of left wing activism masquerading as lawyer training. Seems Chicago is not the exception.

Bob apparently thinks that detaining people pre-trial should be the norm. Color me shocked.

How does the clinic's professors complying statistics and writing a predetermined [its about race!] report help a student become a good lawyer?

Clinics are for training lawyers, not political activism.

That it was predetermined assumes facts not in evidence.

These are your fans, Volokh Conspirators.

And a substantial reason mainstream legal academia disrespects you.

And you are the Rev.olting Jerry L. Sandusky,

seems like you're posting more than last year, so Stuttering John Fetterman wouldn't commute your sentence, but got you some extra time on the Prison computer?? Good for you!!

Frank

Because data and research about the world are relevant to practice in criminal law and other fields. Maybe you don’t need any real world data for your work but actual lawyers do.

If the people are at a significant risk of fleeing and not showing up to trial, should they be held?

Ya think????

It's actually important to consider, and important to consider within the broader crimes typically prosecuted by the US Federal government.

Many people would consider those being prosecuted for immigration-related crimes have a higher inherent risk of fleeing and/or avoiding law enforcement than certain other crimes.

Clinics typically do pro bono work for underserved communities. Apparently to you that is left wing activism. Color me shocked that you don’t think serving the under-served is an important aspect of the law.

In any event a right leaning clinic would be worthless, because there is literally no market for it. What kind of right wing cause could a clinic even do that isn’t already covered by prosecutors offices, corporations/big-law, boutique outfits like the one Paul Clement runs, or any number of right-wing nonprofits?

Seriously. You think people who can afford lawyers are going to go to a clinic? No. But people who are charged with misdemeanors, facing evictions, trying to appeal an unemployment commission decision, etc do.

There are of course plenty of interships, externships, and yes, even clinics that place students in prosecutors' offices.

The clinic's website does seem to focus on the policy work (including this report), although it does appear that the represent individual clients as well (which, to be clear, is good!).

Yes students who are interested in “non-left” or right-wing work have plenty of non-clinic opportunities outside the school. They can even make money at some of them instead of credit.

Plenty of small businesses have as much trouble affording counsel as individuals do. For example, there are few if any clinics out there helping small landlords — not big corporations that own apartment complexes, but a guy who owns a single rental property — against abusive tenants (some of whom may have been assisted by these sorts of clinics.)

The article notes many times that this problem "falls disproportionately on people of color" and implies that racism is the cause (or at least, a cause). I am skeptical and wonder if the better hypothesis is that this problem falls disproportionately on poor people. Granted, there is some correlation between the two variables but it shouldn't be hard to determine which variable is the better predictor. Assuming they have the relevant data, that is...

Also assuming they want to allow the possibility of reaching the politically wrong conclusion.

Or it falls disproportionately on people who committed crimes involving violence, as opposed for instance to property crimes. The possibilities are many. It was the researchers' job to control for those variables. The article makes me wonder whether they bothered.

I could argue that it is not disproportionate to fall more heavily on those accused of crimes of violence rather than property crimes. That seems like a plausibly intended outcome of a functioning pretrial confinement system.

The largest chunk of the "falls disproportionately on people of color" is related to the people typically charged with federal crimes (as opposed to state crimes) and what they are.

A very large chunk of those federal crimes (30%) are immigration related offenses. Neither African Americans, nor Caucasian Americans are typically prosecuted for that...it's overwhelmingly Hispanics.

Another large chunk are drug charges...typically manufacture, trafficking, and sales. A surprisingly high number there are also Hispanics...I would guess trafficking at the southern border.

So, when the article notes "people of color", what they are talking about in this context are Hispanics (and not African Americans). Those numbers for Hispanics being sentenced for crimes (>50%) are not well correlated with how often Hispanics are sentenced for crimes at the state and local level. I would hypothesize, that it's due to the particulars of the federal crimes being prosecuted.

Your description of Jaden Lessnick seems incomplete:

Yeah, right, the problem is the judges misunderstand a law Congress passed in 1984 to keep people in prison before trial.

Not so – the problem is in the initial violation of principle – denying the right to bail in noncapital cases.

This right was one of the rights the people thought they had until around 1984. They certainly thought they had that right in 1789-91, the time of the 9th Amendment.

“Oh, we’ll make just this one concession to allow presumptively-innocent people to be detained without bail prior to trial.” That was when the problem started, not when judges “misinterpreted” some pure and good detention law.

This “misinterpretation” spin represents good czar/bad ministers thinking. It takes criticism off the detention law itself, and leaves room for future “reforms” under the name of “abolishing cash bail.”

Well, take a good look at the bottom of your slippery slope, you “abolish cash bail” fetishists. You think you’ll create a dual system where only political prisoners are denied bail and regular prisoners are turned loose on the community without bail. Even if that wicked scheme were implemented, it would still violate the right to bail. But what if you’re being too clever by half and simply paving the way to a federal-style presumptive-detention regime?

There are no statutory tweaks, the only fix to the problem is the restoration of the constitutional right to bail guaranteed by the 9th Amendment and privileges-and-immunities clause.

And for you partisan hacks who thought denying the right to bail was OK because that means you could detain Trump supporters before trial…now see what your blindness has tolerated.

What is your authority for this proposition?

The 9th was ratified?

The Lord hath delivered you into my hands.

First, my comment in its full context:

“Not so – the problem is in the initial violation of principle – denying the right to bail in noncapital cases.

“This right was one of the rights the people thought they had until around 1984. They certainly thought they had that right in 1789-91, the time of the 9th Amendment.”

“All prisoners shall be bailable by sufficient sureties, unless for capital offences when the proof is evident or the presumption great.” /North Carolina Constitution

https://avalon.law.yale.edu/18th_century/nc07.asp

“All prisoners shall be bailable by sufficient sureties, unless for capital offences, when the proof is evident, or presumption great.” /Pennsylvania constitution

https://avalon.law.yale.edu/18th_century/pa08.asp

“And all prisoners, unless in execution, or committed for capital offences, when the proof is evident or presumption great, shall be bailable by sufficient sureties” /Vermont constitution

https://avalon.law.yale.edu/18th_century/vt02.asp

So tell me, what is your authority for the proposition that the people had given up this right by the time of the 9th Amendment?

I’m not sure I follow. Why does the fact that some states decided to provide for bail in that way suggest that those were the precise contours a right that applied everywhere, even for the governments that didn’t, and enacted conspicuously different constitutional rules about bail?

"the governments that didn’t"

And which governments would that be by 1791?

Cite your authorities.

When we talk about pretrial detention and why it’s supposed to be rarely used, it kind of assumes that jail is a horrible place to be on top of the restraint on Liberty. And in the real world it obviously is. But why?

Any discussion of pretrial detention needs to include discussion about conditions of confinement and how it makes no sense that jails have even worse conditions than prisons in many cases. It’s not supposed to be punishment. Yet the reality is that it’s worse than the punishment the state actually prescribed!

IANAL, but I sometimes wonder why jail costs so much compared to hotels. Security is expensive, but so are all the amenities and maid service in hotels.

I wonder if it would be possible to build a hotel with security in mind for pre-trial detainees. Simple rooms, no mini-fridge or room service. No windows to escape by, inmates have door keys, lobbies have guard-controlled access, room cleaning and changing sheets is once a week and inmates have to be absent, and any room damage means you go to the regular jail. There'd have to be a cafeteria. Probably other things.

I wonder how much it would cost.

If it's run by the government? Take your sane guess and multiply by four.

Oh man, leave that low hanging fruit for the Rev!

Let me try: "Multiply by four? Like clingers who go to fourth tier schools can do math?"

How so? I mean, obviously the imposition is more onerous on any given person if the confinement is extremely unpleasant. But I don't see why that would or should change the constitutional, legal, or even policy analysis particularly significantly.

You don’t think the moral and ethical implications of putting legally innocent people into conditions that are measurably worse than the conditions of the actual punishment for the guilty should significantly affect policy choices? Is that what you’re saying?

And yes it should absolutely affect analysis. If the government is taking your liberty pretrial and placing you in conditions worse than those of its punishment of the guilty that’s an equal protection problem and a due process problem.

No LTG,

The argument being made is that the imposition on liberty, regardless if you're in a nice garden level prison or in a rough city jail cell is still that...an imposition on liberty. And the relative conditions of your pre-trial detention should not affect whether you are placed in pre-trial detention in the first case.

There are real reasons for pre-trial detention. Flight risks and dangers to the community, respectively. But the evaluation of that flight risk or danger to the community should not hinge on the relative "niceness" of your pre-trial detention conditions.

“still that…an imposition on liberty.”

This is stunningly obtuse.

There’s a world of difference between what Kalief browder experienced and what someone locked in a healthy and safe environment would experience. There’s a major difference between incompetent jail guards letting pregnant woman give birth on cell floors and a secure environment that has rudimentary sanitation.

“And the relative conditions of your pre-trial detention should not affect whether you are placed in pre-trial detention in the first case.”

That’s a normative position you don’t really defend. Why shouldn’t it matter that we’re putting someone in worse conditions than prison to prevent them from fleeing. Especially on offenses that won’t necessarily lead to prison! People are held in jail for longer than they would actually serve.

And in any event that obviously doesn’t affect whether we should improve conditions in the first place! Just because pretrial detention exists and is necessary doesn’t mean it has to be the worst version of it. You haven’t made any argument as to why conditions shouldn’t be improved.

LTG,

If you want to argue to improve jail conditions, then go ahead. But you're shifting into a very different argument. In your words...

"Why shouldn’t it matter that we’re putting someone in worse conditions than prison to prevent them from fleeing."

What that implies is that you view whether or not someone should be put into pre-trial detention, based on the condition of the jail cells themselves. And I don't agree with that. Do you agree with that? That the condition of the jail cells should dictate whether someone goes to pre-trial detention or not?

Yes absolutely. You should absolutely consider whether putting someone charged with a misdemeanor or a low level felony in more dangerous conditions than they would experience if they pleaded guilty is appropriate when considering a bond.

If pretrial detention conditions are bad, that’s obviously a problem that should be addressed. (I don’t accept your premise that they are typically “measurably worse than the conditions of the actual punishment for the guilty”, though I’m sure that is the case for some facilities—as you note, Riker’s Island seems to be an exceptionally bad place.)

But I don’t think the argument being expressed here (i.e. that federal defendants are being unnecessarily and improperly detained) in any way “assumes that jail is a horrible place to be on top of the restraint on Liberty.” And to the extent the argument is well-founded, the problems need to be addressed, regardless of how well the inmates are being treated. Nor would better treatment for the inmates who are being improperly detained serve as an appropriate solution.

Pretrial detention relies on a fiction -- that the "purpose" of pretrial delay is not punishment (ala Alice in Wonderland, 'Sentence first - verdict afterwards.') but rather simple administrative necessity. It is curious, therefore, that people allegedly NOT being punished are kept side by side, in the same conditions, with people who ARE being punished. Some legal theories argue that the conditions are irrelevant, that only the "intent" of the government counts -- and the government does not "intend" to punish. It is simply an unfortunate corollary of the administrative detention. [similarly, some define "torture" as only that 'intended' to cause pain and suffering. If you 'intend' only to extract information, the pain and suffering is regrettable, but does not amount to torture.]

Of course, the legal position that pretrial confinement is not punishment is somewhat at odds with politicians like Joe Arpaio, who bragged that he was punishing everyone in his jail, and he didn't care if you were convicted or merely charged, all detainees were the same (even if the "law" said some were still innocent).

The Supreme Court in Salerno was simply not willing to buck the popular tide that was rolling anti-crime, sometimes hysterically so (ritual satanic abuse, I'm looking at you!). Judges are the modern day 'Vicars of Bray.'

Agreed.

Agreed.

In U.S. v. Salerno, 481 U.S. 739 (1987), SCOTUS put a big stamp of approval on pretrial detention and found the Bail Reform Act was constitutional. The majority assured everyone that:

"In our society liberty is the norm, and detention prior to trial or without trial is the carefully limited exception."

A fine example of how such assurances from the Courts should not be relied on too heavily (if at all). The "carefully limited exception" has largely become the rule.

I think the dissent is worth citing. It begins (J. Marshall):

"This case brings before the Court for the first time a statute in which Congress declares that a person innocent of any crime may be jailed indefinitely, pending the trial of allegations which are legally presumed to be untrue, if the Government shows to the satisfaction of a judge that the accused is likely to commit crimes, unrelated to the pending charges, at any time in the future. Such statutes, consistent with the usages of tyranny and the excesses of what bitter experience teaches us to call the police state, have long been thought incompatible with the fundamental human rights protected by our Constitution. Today a majority of this Court holds otherwise. Its decision disregards basic principles of justice established centuries ago and enshrined beyond the reach of governmental interference in the Bill of Rights."

SCOTUS should never have reached the merits in Salerno. As Justice Thurgood Marshall's dissent indicates, one of the defendants in the case had been sentenced to 100 years imprisonment in another, unrelated prosecution. The other defendant had become a government informant prior to certiorari being granted, and the government agreed to his release on bail in order that he might better serve the government's purposes. 481 U.S., at 756-58.

The proper course of action would have been to vacate the opinion of the Court of Appeals (which had ruled in favor of the defendants and declared part of the Bail Reform Act facially unconstitutional) as moot.

You list 4 problems, but skip over the "zeroth" problem: The proliferation of federal criminal laws. There certainly are a lot of them these days, for a level of government that deliberately wasn't given the general police power!

Maybe if the courts hadn't found so many excuses to permit the federal government to exercise that power anyway, it would be less of an issue?

Agreed that that's a problem, but when we're talking about percentage of defendants being detained, it doesn't really address that particular facet of the issue.

While I'm sympathetic to some of the criticisms.... this is a lot of ideological opinion masquerading as science. No look at the benefits of pre-trial detention. Ignoring that the minorities are committing more crimes. No distinction between being able to pay and choosing not to pay. Countless assertions of illegality with no explanation. Talking about fear driving the increase but no mention of what the fear is of or the reasonableness of that fear.

You think there are lots of people saying, "Sure, I could post bail… but I'd rather sit in jail?" (It rhymes, but it isn't very likely.)