The Volokh Conspiracy

Mostly law professors | Sometimes contrarian | Often libertarian | Always independent

Freedom Denied Part 1: How the Culture of Detention Created a Federal Jailing Crisis

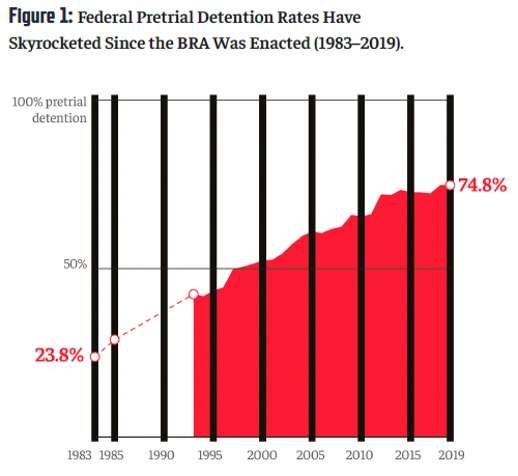

Our Federal Criminal Justice Clinic at the University of Chicago Law School recently released the first comprehensive national investigation of federal pretrial detention—Freedom Denied: How the Culture of Detention Created a Federal Jailing Crisis. We conducted this study to understand why the federal system jails 75% of those pending trial, even though they are presumed innocent and have not been tried or convicted. We discovered that federal judges routinely lock people in jail in violation of the law, which increases jailing rates and exacerbates racial disparities.

In 1987, the Supreme Court upheld the constitutionality of jailing federal defendants before trial in United States v. Salerno, declaring, "In our society, liberty is the norm, and detention prior to trial or without trial is the carefully limited exception." At that time, just 29% of people charged with federal crimes were jailed before trial; the rest were released back to their families. But today, pretrial jailing has become the norm, and we conclude that "the culture of detention" is to blame:

This Report reveals a fractured and freewheeling federal pretrial detention system that has strayed far from the norm of pretrial liberty. This Report is the first broad national investigation of federal pretrial detention, an often overlooked, yet highly consequential, stage of the federal criminal process. Our Clinic undertook an in-depth study of federal bond practices, in which courtwatchers gathered data from hundreds of pretrial hearings. Based on our empirical courtwatching data and interviews with nearly 50 stakeholders, we conclude that a "culture of detention" pervades the federal courts, with habit and courtroom custom overriding the written law. As one federal judge told us, "nobody's … looking at what's happening [in these pretrial hearings], where the Constitution is playing out day to day for people."

The culture of detention is so deeply engrained that it often overrides explicit protections and requirements codified in the Bail Reform Act:

Our primary explanation for the legal violations documented in this Report is the phenomenon we have labeled the culture of detention…. Even when the [statute] contains clear instructions, judges and prosecutors frequently ignore those instructions in favor of longstanding district practices, substituting courtroom habits for the plain text of the statute and overincarcerating people in the process…. [O]ne judge we interviewed justified those deviations by saying: "Oh, that's just the way we do it."

Media coverage of the report corroborates that these "systemic problems are largely the result of what judges and advocates [say] … is a poorly-written, war-on-drugs-era statute known as the Bail Reform Act of 1984, an over reliance on prosecutorial discretion, and risk-averse magistrate judges and federal defenders."

Our report identifies four distinct problems.

First, we found that federal magistrate judges misunderstand and misapply the Bail Reform Act's legal standard at Initial Appearance Hearings, the first bail hearing:

Our study found that there is a severe misalignment between the legal standard that applies during Initial Appearance hearings and the practice that unfolds in courthouses around the country. Judges routinely ignore the legal standard in § 3142(f) [of the Bail Reform Act] and sometimes jail people unlawfully….

Our most troubling finding was that, in 12% of Initial Appearances where the prosecutor was seeking detention, judges detained people illegally.

We also found disturbing racial disparities stemming from this problem:

Moreover, these unlawful detentions were carried out in a racially disparate way…. The unlawful detentions we observed are just the tip of the iceberg…. This is not just an isolated situation in which a few judges or attorneys slightly misunderstand the law; rather, there is a pervasive, systemic deprivation of liberty that is not authorized by statute or case law.

Second, although federal law requires judges to provide lawyers for everyone who appears in court, we documented "a national access-to-counsel crisis":

In many federal courts, judges lock poor people in jail without a lawyer during their Initial Appearance, in violation of federal law. Our study uncovered a national access-to-counsel crisis: judges in more than one-quarter of the 94 federal district courts do not provide every arrestee with a lawyer to represent them during the Initial Appearance….

Locking people in jail without counsel violates the U.S. Code and the Federal Rules of Criminal Procedure, may be unconstitutional, and is not sound public policy….

Unsurprisingly, our data show that detention rates at the Initial Appearance increase as representation decreases.

This access-to-counsel crisis falls disproportionately on people of color:

Black and Latino individuals were also more likely than white individuals to face the Initial Appearance without the full assistance of counsel. While just 13% of white arrestees were only partially represented at their Initial Appearance, over 30% of Black and Latino individuals faced the same problem—more than twice as many. Moreover, white arrestees received full representation in 80% of their Initial Appearances, while Black and Latino arrestees received full representation in 60% and 53% of their Initial Appearances, respectively.

Third, we learned that "[c]ourts misunderstand and misapply the [statutory] presumption of detention [that applies in most federal drug cases], further contributing to the culture of detention":

The statutory presumption of detention that applies to many federal offenses during the Detention Hearing is a primary driver of sky-high pretrial detention rates. The practice surrounding the presumption—and the presumption itself—contradict the sacred promise of "innocent until proven guilty" and reverse the BRA's "clear preference for pretrial release."

This misapplication of the presumption of detention falls most heavily on people of color:

The burden of the presumption of detention is not borne equally by all arrestees. Using sentencing data as a proxy, we estimate that most arrestees facing a presumption are people of color, since they make up 75% of those convicted of qualifying drug offenses nationwide. In this study, the proportion of people of color was even higher: 89% of presumption cases involved people of color, while only 11% involved white arrestees.

Fourth, we found that judges regularly disregard the Bail Reform Act's prohibition against jailing people who cannot afford to pay a monetary bail—also contributing to racial disparities:

Our courtwatching study shows that federal judges consistently impose financial conditions of release that result in pretrial detention. This practice violates the explicit statutory language of the Bail Reform Act, perpetuates a system where wealth buys release and people are jailed for poverty, and has a disproportionate racial impact. These detentions, which violate the law, contribute to rising detention rates as well as racial and socioeconomic disparities in the federal system.

Overall, we found that high federal jailing rates fall overwhelmingly on people of color and low-income individuals. In our study, people of color were significantly more likely to be illegally jailed at their Initial Appearance hearing, to be deprived of counsel at that hearing, and to be jailed unlawfully on financial conditions they could not meet.

This culture of pretrial detention inflicts severe and enduring damage on people and their communities:

Pretrial detention has myriad pernicious consequences, harming individuals, as well as their loved ones and communities. First, it prevents people from accessing necessary healthcare, subjects them to dangerously overcrowded living conditions, exposes them to physical violence, and increases their vulnerability to infectious diseases. Second, people who are jailed pending trial in the federal system are more likely to be convicted, sentenced to longer terms of incarceration, and sentenced pursuant to a mandatory minimum than their released peers. Finally, pretrial detainees experience employment and housing instability at a higher rate than their released peers, and they can lose custody of their children after even a few days in jail.

The crisis that our study identifies is extraordinarily serious, but it is not insurmountable. The simple solution is that judges must adhere more closely to the letter of the law. Our report provides recommendations for judges and attorneys alike to realign courtroom practices with the protections ensconced in the Bail Reform Act:

Fear may inform many of the harms we identify in this Report. It is incumbent upon judges to act boldly and to be guided by data, not institutional pressures…. We hope that our Report empowers federal judges to continue shifting the culture that has brought the federal system to this calamitous point…. Ultimately, federal judges have the power to uphold the rule of law, to make detention prior to trial the rare exception, and to be champions of liberty.

This is the first post of a five-part series. Later posts will take a closer look at each of the four problems and our recommendations. All block-quoted material comes from the Clinic's Report: Alison Siegler, Freedom Denied: How the Culture of Detention Created a Federal Jailing Crisis (2022).

Show Comments (59)