The Volokh Conspiracy

Mostly law professors | Sometimes contrarian | Often libertarian | Always independent

How Body-Worn Cameras Are Changing Fourth Amendment Law

A subtle change, but a real one.

I read a lot of new Fourth Amendment cases, and in the last year or two I've noticed something interesting: Body-worn cameras seem to be changing Fourth Amendment law. To be clear, the cameras aren't having an explicit effect. Courts don't have camera-specific rules. But body-worn cameras are changing how courts review police-citizen interactions. The ability to "go to the tape" allows courts to reconstruct in detail exactly what happened. And that lets courts scrutinize much more closely what the police are doing—and to adopt doctrines that rely on that second-by-second scrutiny.

A number of the relevant cases involve the length of traffic stops. Traffic stops are the most common police-citizen interaction, and a stop for speeding or a broken taillight can often turn into something more. Given that, what happens during a traffic stop is super important. One of the important doctrinal tool to limit traffic stops (maybe the most important) is the time element. In Rodriguez v. United States, in 2015, the Court held that the permitted time of a traffic stop is determined by the time that an officer actually did or should have completed the mission of the stop — the mission being the safety-related rationales that permit traffic stops in the first place, like writing a ticket, making sure the car is registered, the driver has a valid license, etc.

Rodriguez came at an interesting moment. It introduced a time-based test at a time when police body-worn cameras were coming into widespread use. And by creating a test that distinguishes things within the mission of the stop from things outside the mission, the Court created a test that in theory could hinge on pretty specific, second-by-second inquiries into time. Before body-worn cameras, though, that would have been essentially impossible. Courts trying to reconstruct what happened during traffic stops would be stuck with the old tools of relying on memory from a long past event.

Body-worn cameras have changed that. In the context of traffic stops, they allow a second-by-second reconstruction of everything that happened. They allow a scrutiny of each and every question, and of each and every movement. Of course, cameras can't capture everything; you still might only get a partial picture. But often the cameras capture a lot, especially in the context of a traffic stop's duration. And that lets courts adopt doctrinal rules that rely on the new camera technology in their application.

Take, for example, State v. Riley, 514 P.3d 982 (Idaho 2022). It's a pretty ordinary traffic stop case in the books. A stop for expired tags leads to a suspicion there are drugs in the car, which leads to another officer coming to walk a drug-detection dog around the car. The dog alert leads to a search of the car, and they find drugs. Before body-worn cameras, this would have received no scrutiny at all.

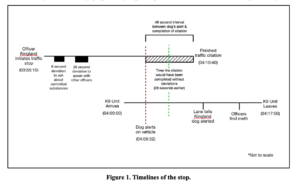

But body-worn cameras let the court do something different. The opinion by Justice Moeller features a second-by-second reconstruction of every relevant question and every relevant pause, which leads the court to scrutinize each question to decide if it was inside or outside the mission of the stop. The court can then subtract out the precise seconds added by the outside-the-mission questions and pauses to determine if the dog sniff occurred within the proper period of a stop. According to the court, the officer spent exactly 8 seconds asking the driver if there were drugs in the car, and later spends another 20 seconds discussing the situation with backup officers who arrived at the scene. The court's opinion includes this chart to explain the timeline:

Ultimately, the court rules that the government wins by 20 seconds. That is, although the outside-the-mission goings-on added 28 seconds, the dog alerted 48 seconds before the first officer finished writing his ticket for the stop. So the dog alerted within the time window that would have existed without the outside-the-mission conduct by 20 seconds.

In this particular case, I don't think the camera changes the ultimate outcome of the case. But it's the methodology, I think, that matters. The court's method for determining if the Fourth Amendment was violated rests on being able to scrutinize timestamps on a video and calculate hypothetical timeframes. I doubt a court would have thought to do that in a world without video. The available technology changes how the doctrine can be applied, and that, in a practical sense, helps to change what the doctrine is.

Anyway, I'm not sure how far these changes will go over time. I assume we're moving in the direction of having more and more body-worn cameras, and maybe more video evidence generally. So we'll see whether or how the new forms of evidence have a small or large effect on doctrine. But it seems like something to watch. It's a subtle difference, but I think it's a real one.

Show Comments (36)