The Volokh Conspiracy

Mostly law professors | Sometimes contrarian | Often libertarian | Always independent

Football Coach's Display of "All Lives Matter" Poster May Have Been Protected by First Amendment

From Beathard v. Lyons, decided Thursday by Judge James Shadid (C.D. Ill.):

The following facts are taken from Plaintiff's Complaint, which the Court accepts as true for the purposes of a motion to dismiss. Plaintiff filed a complaint alleging that he was terminated from his position because of his viewpoint on a matter of public concern—the Black Lives Matter Movement ("BLM"). Plaintiff was employed by Illinois State University ("ISU") as a football coach. In mid-August of 2020, ISU's Athletic Department printed posters for the BLM Movement. Many staff members pasted the poster onto their doors, and one was pasted onto Plaintiff's office door. An image of the poster has been reproduced below:

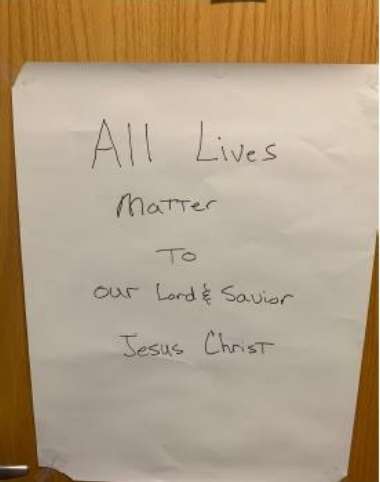

Plaintiff removed the poster from his door and replaced it with one that embodied his own personal beliefs on the matter. An image of Plaintiff's poster ("replacement poster") has been reproduced below:

Plaintiff's poster was pasted on his office door for approximately two weeks without incident. On August 29, 2020, Brock Spack …, Head Football Coach, asked Plaintiff to remove the poster from his door. Plaintiff removed the poster and Spack thanked him..

During this time, many players and students at ISU demanded that the Athletic Department publicly support the BLM Movement. This demand resulted in missed practices, and a boycott against ISU Athletics after Athletic Director Larry Lyons … stated "All Redbird Lives Matter," to much public backlash from both players and students. On August 30, 2020, an image of the replacement poster on Plaintiff's door was shared with ISU football players. Players continued to boycott practices, and Plaintiff was informed by Spack that he was in trouble for his replacement poster. On September 2, 2020, Plaintiff was terminated from his position as the offensive coordinator because Spack didn't "like the direction of the offense." The decision to terminate Plaintiff was supported by AD Lyons. Plaintiff was placed in a different position where he received the single assignment of researching how other football coaches handled COVID-19. Plaintiff was replaced by two new coaches.

Plaintiff asserts that his termination by Spack and Lyons was direct retaliation for his expressing his viewpoint on the BLM Movement….

As both parties point out, the main issue in this case is whether Plaintiff was acting pursuant to his official duties when he put the replacement poster on his door, and thus, whether his speech was private speech or government speech. When a public employee makes a statement pursuant to their official job duties, he is not protected by the First Amendment, as he would if speaking as a private citizen. Garcetti v. Ceballos (2006). As pointed out by Plaintiff, speech can be considered part of one's official duties if it "owes its existence to a public employee's professional responsibilities"; is "commissioned or created" by the employer; "is part of what [the employee] was employed to do; is a task the employee "was paid to perform"; and "[has] no relevant analogue to speech by citizens who are not government employees." Coaches, like teachers or students, do not "shed their constitutional rights to freedom of speech or expression at the schoolhouse gate." Defendants argue that this District has specified that one's job duties are not limited to their formal job description, and the Court must evaluate "whether the speech is intimately connected with the speaker's job and to whom the speaker directed the speech."

The recent Supreme Court decision Kennedy v. Bremerton Sch. District further discusses this issue. Kennedy makes it clear that when a high school football coach engages in prayer after a high school football game, he is not engaged in speech that falls within his ordinary job duties. Just because a student or other staff members can see one exercising their freedom of speech does not transform private speech into government speech. During the football game, the coach's "prayers did not 'ow[e their] existence' to Mr. Kennedy's responsibilities as a public employee." The Court explained that while not everything a coach says in the workplace is considered government speech, one must evaluate the substance of the speech as well as the circumstances around the speech to determine whether or not the speech was within one's job duties. After such an evaluation, the Court held Mr. Kennedy's speech to be private speech outside of his official job duties, and concluded the school violated his rights under the First Amendment by terminating him….

The Court does not find that Plaintiff's actions were taken in furtherance of his official job duties. In putting up the replacement poster, Plaintiff was expressing his personal views, which in no way "owed their existence" to his responsibilities as a public employee. was not paid by the University to decorate his door or to use is to promote a particular viewpoint, he was employed to coach football. Further, ISU holds an Anti-Harassment and Non-Discrimination Policy, which states:

"Illinois State University … is strongly committed to the ethical and legal principal that each member of the University Community enjoys the right to free speech. The right of free expression and the open exchange of ideas stimulates debate, promotes creativity, and is essential to a rich learning environment… As members of the University Community, students… and staff have a responsibility to respect others and show tolerance for opinions that differ from their own…"

Under such a policy, Plaintiff should enjoy the right to express his personal viewpoint, within reason. While the opinion Plaintiff posted on his door may have been different than that of the majority, the BLM Movement was not a sanctioned school movement. Just as the ISU Athletic Department and staff were able to hang posters supporting the BLM Movement, Plaintiff had the protected right to create and hang his own poster, supporting his own message. There was no school policy prohibiting Plaintiff decorating his door in whichever fashion he might choose. Further, Plaintiff was not required, as a term of his employment, to either refrain from decorating his door or to decorate it in a certain way. Here, Plaintiff was not acting in his official job duties when he placed the poster on his door, and therefore, his was private speech protected by the First Amendment, satisfying the first of the two elements of a prima facie case of retaliation….

The second step in the [First Amendment retaliation test] is to evaluate … [whether] "… the protected speech caused, or at least played a substantial part in, the employer's decision to take adverse employment action against" [the employee]…. The employer's stated reason for the termination was that Spack "didn't like the direction of the offense." However, in their Memorandum in Support of Motion to Dismiss, Defendants assert that the University was responding to the students' reactions to Plaintiff's speech, and not the speech itself. This termination … is a motivating factor, as his speech "played a substantial part in" the decision to terminate him, thus satisfying the second element….

Both parties correctly state that if a public employee's speech is on a matter of public concern, and that employee is terminated because of that speech, that termination may be justified by the employer. Pickering v. Board of Education (1968). Pickering requires the Court to "balance between the interests of the teacher, as a citizen, in commenting upon matters of public concern and the interest of the State, as an employer, in promoting the efficiency of the public services it performs through its employees." … [But]

Pickering contemplates a highly fact-specific inquiry into a number of interrelated factors… Pickering balancing is not an exercise in judicial speculation. While it is true that in some cases the undisputed facts on summary judgment permit the resolution of a claim without a trial, that means only that the Pickering elements are assessed in light of a record free from material factual disputes… This is precisely what the Supreme Court did in Connick, where its Pickering analysis looked to the actual testimony of the employee's supervisor regarding the potential impact of the employee's speech and then evaluated the other evidence in the record to determine whether it supported the employer's fears…. We are not entitled to speculate as to what the employer might have considered the facts to be and what concerns about operational efficiencies it might have had, once the record shows what those concerns really were.

Because the parties have not yet had the opportunity to conduct discovery at this stage of the litigation, this Court cannot evaluate the facts under Pickering without engaging in speculation….

Congratulations to Adam W Ghrist (Finegan Rinker & Ghrist) and Douglas A. Churdar, who represent plaintiff.