The Volokh Conspiracy

Mostly law professors | Sometimes contrarian | Often libertarian | Always independent

Cost-Lowering Slippery Slopes as Multi-Peaked Preferences Slippery Slopes

[This month, I'm serializing my 2003 Harvard Law Review article, The Mechanisms of the Slippery Slope.]

Cost-lowering slippery slopes, it turns out, are a special case of a broader mechanism—the multi-peaked preferences slippery slope.

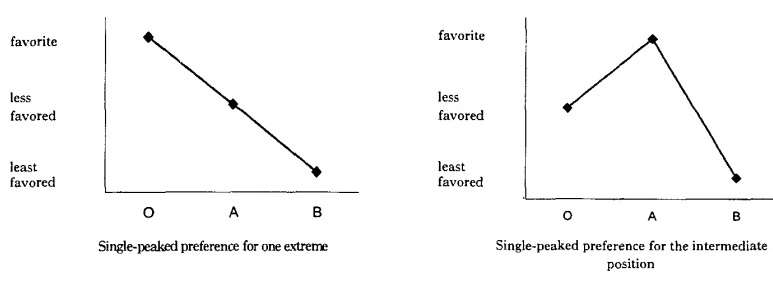

In many debates, one can roughly divide the public into three groups: traditionalists, who don't want to change the law (they like position 0); moderates, who want to shift a bit to position A; and radicals, who want to go all the way to position B. What's more, one can assume "single-peaked preferences": both traditionalists and radicals would rather have A than the extreme on the other side. We can represent the preferences as follows, which is why the preferences are called "single-peaked":

If neither the traditionalists nor the radicals are a majority, the moderates have the swing vote, and thus needn't worry much about the slippery slope. Say that 30% of voters want no street-corner cameras (0), 40% want cameras but no archiving and face recognition (A), and 30% want cameras with archiving and face recognition (B). The moderates can join the radicals to go from 0 to A; and then the moderates can join the traditionalists to stay at A instead of going to B. So long as people's attitudes stay fixed, there's no slippery slope risk: those who prefer A can vote for it with little danger that A will enable B. {I assume here that the enactment of A doesn't change people's preferences; in later posts, I will relax that assumption, and consider the possibility that enacting A might actually alter people's attitudes about B.}

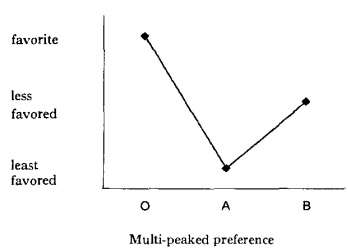

But say instead that some people prefer 0 best of all (they'd rather have no cameras, because they think installing cameras costs too much), but if cameras were installed they would think that position B (archiving and face recognition) is better than A (no archiving and no face recognition): "If we spend the money for the cameras," they reason, "we might as well get the most bang for the buck." This is a multi-peaked preference—these people like A least, preferring either extreme over the middle.

Let's also say that shifting the law from one position to another requires a mild supermajority, say 55%; a mere 50%+1 vote isn't enough because the system has built-in brakes (such as the requirement that the law be passed by both houses of the legislature, the requirement of an executive signature, or a more general bias in favor of the status quo). We can thus imagine the public or the legislature split into several different groups, each with its own policy preferences and its own voting strength; where there's a + in the columns labeled 0→A, A→B, and 0→B, that indicates that the group would vote to move from the first position to the second:

| Group | Most prefers | Next preference | Most dislikes | 0→A | A→B | 0→B | Attitude | Voting strength |

| 1 | 0 | A | B | "As little surveillance as possible, either (1) as a matter of principle, or (2) because we prefer surveillance level A as a matter of principle, but think cameras are too expensive" | 26% (20% for (1) + 6% for (2)) | |||

| 2 | 0 | B | A | + | "Cameras are too expensive, but if the money is spent, might as well get as much surveillance for it as possible" | 18% | ||

| 3 | A | 0 | B | + | "We prefer moderate surveillance level A, and definitely no more" | 14% | ||

| 4 | A | B | 0 | + | + | "We prefer surveillance level A, and definitely no less" | 0% (in this example) | |

| 5 | B | 0 | A | + | + | "We want maximum surveillance, but if we can't have that, we'd rather have no surveillance instead of A" | 0% | |

| 6 | B | A | 0 | + | + | + | "We want maximum surveillance, and cost isn't a concern" | 42% |

This preference breakdown is exactly the same as in the table in the first cost-lowering slippery slope post; and, as in that table, the direct 0→B move fails, because it gets only 42% of the vote (group 6), but the 0→A move succeeds with 56% of the vote (groups 3 and 6) and then the A→B move succeeds with 60% of the vote (groups 2 and 6). {Any proposed B→0 move will fail because group 2, which originally preferred 0 over B, no longer prefers it, since the money has already been spent and the cameras bought.} As before, members of group 3 must now regret their original vote for the 0→A move, because that vote helped bring about result B, which they most oppose.

Multi-peaked preferences thus make the moderate position A politically unstable—which means that implementing A can grease the slope for a B that otherwise would have been blocked.

Editor's Note: We invite comments and request that they be civil and on-topic. We do not moderate or assume any responsibility for comments, which are owned by the readers who post them. Comments do not represent the views of Reason.com or Reason Foundation. We reserve the right to delete any comment for any reason at any time. Comments may only be edited within 5 minutes of posting. Report abuses.

Please to post comments

Having taken statistics at a relatively early age, I prefer "multimodal" to "multi-peaked".

Eugene should address The Tipping Point.

The slow accumulation of snow results in an avalanche. The slow accumulation of regs and taxes results in our current Commie tyranny by scumbag lawyers.

The slow accumulation of technology results in a total surveillance state beyond the imagination of any science fiction writer of a few years ago. The bought off scumbag lawyer does nothing about it. The slow accumulation of social pathology results in a failed state. The rent seeking scumbag lawyer does nothing about it. He is getting his $trillion in worthless make work toxic procedure.

At some point, the quiet but seething resentment of the ordinary person results in an ass kicking.

This assumes the middlish position is the masses, who will hold. It takes time for people to build up support for a law, internally adopting it as the moral position. If it that happens at all.

Remember Prop 8? Passed with flying colors. The Democrats were shocked, shocked all the Latinos they thought were their good buddies voted for it. Nevermind. The party literally named after Democracy, and who uses patter about it as reason to overturn tired, long dead old white men's political philosophies, ran to the courts to overturn it.

We love democracy, until we don't.

Anyway, if such rulings got overturned, there is no solid middle to hold. Same for abortion, which never swayed half the country, and half of the rest may be tepid in their support, it being The Thing To Believe.

I would be bothered by it being overturned, but I have no problem with the thwaring of democracy to uphold rights, gay or abortion. But I am not of a party that holds The Will of The People as the highest of values.

Democracy is the tool of Freedom, of free people. It is not its master. In any collision between freedom and democracy, freedom should win, unless a supermajority approves giving government a radical power over it.

This country is great because it is free. Not because it is a democracy.

Since every case has unique features, one can come up with a named category for every case if one wants. To be useful, a categorization has to classify things into a relatively small number of different sets. Categorization always loses information, as there are always identifying features it does not capture. Even a categorization with one member per category only identifies one distinguishing feature and loses the others. The tradeoff between number of categories and information loss is always somewhat arbitrary.

Is this many categories helpful? I don’t think so. It seems to be based on the naive idea that if you can identify a distinguishing feature, you ought to create a new category. This is in turn based on the really naive idea that categories completely identify the differences, rather than merely abstracting a small of key differences considered especially important and losing the rest.

Time and again lawyers seem to operate under the delusion that their system of categories provides, or should provide, a complete guide to reality. I find this astonishingly naive. But it seems to be just as common a delusion as thinking the world has only two possible alternatives, so that if you refute alternative A, you necessarily establish alternative B.

It comes from thinking the categories that come to ones head are real and actually correspond to the world as it is, rather than being useful fictions that we basically make up because they are often helpful. We pretend the categories in our mind capture all information, not just the information useful for our particular purposes. We pretend what happens to be useful to us is absolute, real, and ought to be useful to everybody.