The Volokh Conspiracy

Mostly law professors | Sometimes contrarian | Often libertarian | Always independent

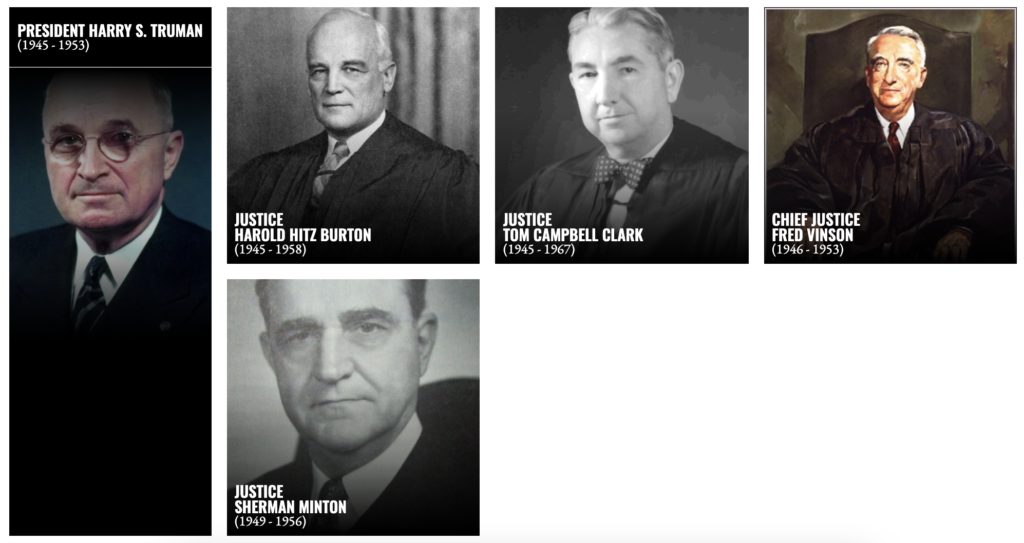

Today in Supreme Court History: April 12, 1945

4/12/1945: President Harry Truman's inauguration. He would make four appointments to the Supreme Court: Chief Justice Vinson, and Justices Burton, Clark, and Minton.

Editor's Note: We invite comments and request that they be civil and on-topic. We do not moderate or assume any responsibility for comments, which are owned by the readers who post them. Comments do not represent the views of Reason.com or Reason Foundation. We reserve the right to delete any comment for any reason at any time. Comments may only be edited within 5 minutes of posting. Report abuses.

Please to post comments

Thee of them were there for Brown v. the Board of Education, but still pretty mediocre.

HST was a mediocre man who picked mediocre judges, some of them cronies. But you can never take away from him the strength of character he showed when he was thrust into the Oval Office at such a critical time, having to make huge decisions on matters as to which they had deliberately kept him in the dark.

"If you go to a publisher and say you want to write that Harry Truman was a blunt-spoken Missourian who made some unpopular decisions but was vindicated by history, the publisher will pick you up by the neck and toss you into the street, because there are already bales of such books on the market. But if you claim to have uncovered evidence that Harry Truman was a Soviet ballerina, before long you'll be on national morning television..."

Dave Barry, Dave Barry's Greatest Hits (New York: Ballantine Books, 1988), p. 179

Really, the Truman Judges simply took the judicial deference the New Deal Judges applied to federal economic regulation and extended the logic to federal laws liberals *didn't* like.

In other words, mediocre.

It is perhaps historically ironic that Democratic president Truman's appointees are generally viewed as having moved the court to the right, with his four picks (plus Frankfurter) giving the "conservatives" a relatively solid 5-4 majority on the Court from 1949-1953. It would be Republican president Eisenhower's appointees (namely Warren and Brennan) that would tip the Court to the left.

The Democrats were a largely conservative party until the '60s, while Republicans were the more progressive party. Any irony you perceive is just an artifact of the Southern Switch when they essentially traded platforms.

Not especially. Some of Roosevelt's selections Douglas and Black were the leaders of the liberal wing of the Court for decades, Rutledge, Murphy, and Stone (whom FDR elevated to Chief) were reliable progressives as well.

It might be fairer to say both parties had conservative and progressive wings. Chief Justice Taft was in poor health for at least the final year of his tenure, but held on until President Hoover assured him Justice Harlan Stone (a progressive Coolidge pick) would not succeed him. The Vinson Court was something of a brief conservative period between the progressive Stone Court and the ultra-progressive Warren Court.

...if by "conservative" you mean they tended to be consistent when it came to judicial deference, upholding restrictions on both economic and non-economic rights, while another faction of Justices denied economic rights but tried to uphold non-economic rights.

As to Presidential authority - the Court struck down Truman's seizure of the steel plants on the grounds the President had gone beyond (or contrary to) the will of Congress. The Truman justices divided 2-2.

These are admittedly imprecise terms that change over time, but in this context, "conservative" means generally judicial restraint and deference to Congress, while "liberal" (my use of "progressive" was a bad word choice) means a greater interest in individual rights (including finding new ones).

But regardless of what labels you prefer to use, there were two readily identifiable blocs in the Vinson Court as evidenced by their voting patterns. (I might note that the four "liberals" were a slightly more reliable bloc and, on occasion, might cobble a majority with another justice or two.) And when Murphy and Rutledge died within a few months of each other in 1949, their replacements (Clark and Minton) tended to side with the "conservatives", turning a 5-4 Court into a 7-2 Court, and Black and Douglas would write nearly as many dissents as the other justices combined.

Some of the statistics are remarkable. In the October 1949 term, Vinson and Clark would only disagree one time in 69 cases. Vinson and Minton would only disagree in six of 78 cases. Conversely, Douglas would disagree with Jackson in 64% of cases and Frankfurter in 56% of cases; Black would disagree with Jackson in 46% of cases and Frankfurter in 43%. Douglas and Black would disagree with each other in just 12% of cases. By way of a modern comparison, as of 2014, the sitting justices who disagreed the most were Thomas and Ginsburg, who disagreed 34% of the time.

Russell W. Galloway Jr., The Vinson Court: Polarization (1946-1949) and Conservative Dominance (1949-1953), 22 Santa Clara L. Rev. 375 (1982). (available online)

Jeremy Bowers, et al., Which Supreme Court Justices Vote Together Most and Least Often. New York Times (July 3, 2014). (available online)