The Volokh Conspiracy

Mostly law professors | Sometimes contrarian | Often libertarian | Always independent

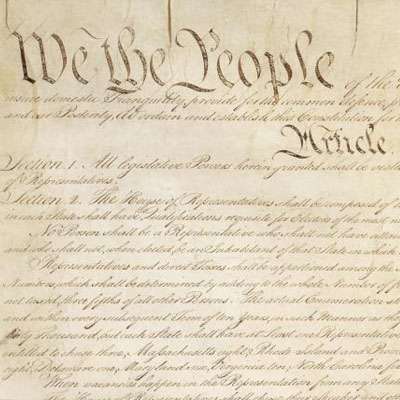

Today in Supreme Court History: September 28, 1787

9/28/1787: Confederation Congress adopts Constitution and sends it to the states.

Editor's Note: We invite comments and request that they be civil and on-topic. We do not moderate or assume any responsibility for comments, which are owned by the readers who post them. Comments do not represent the views of Reason.com or Reason Foundation. We reserve the right to delete any comment for any reason at any time. Comments may only be edited within 5 minutes of posting. Report abuses.

Please to post comments

Um, no. Congress didn’t “adopt” the Constitution. The framers knew that if put to a vote Rhode Island (which had boycotted the Convention) would veto it.

All Congress did was agree to pass the document on to the states.

More bad history from Josh.

captcrisis...It was sheer brilliance how the Founders managed the entire ratification process. Think about it: In no colony was the Constitution ever put to a popular vote. It was ratified with special 'conventions' that were specifically designed to bypass a direct vote by the electorate. And it worked. 🙂

True.

Yeah, 'We the People' is near unmitigated bullshit. It almost always amazes me when conservatives gnash their teeth and rend their garments over, say, blacks and feminists being critical of the country given that. They go apeshit over an executive order to get a free, approved vaccine for Pete's sake, imagine if the political order had been framed with no regard to them!

Cite? lol

You need a cite for the idea that the white male framers designed the constitutional system without regard to the needs or desires of black people, most of whom were enslaved, women, and natives?

He's a gibbering idiot.

"free"

As usual, unhinged leftists have to lie to make their points.

I didn't pay for my vaccine, did you?

Somebody paid for it, even if it was made with slave labor

Queenie, there's no such thing as "free" stuff. There's only stuff that somebody else paid for. That's the sort of thing you should always keep in mind.

That's not what free means "given or available without charge"

Sometimes it means, "Taken from somebody else, or somebody else given no choice about paying for it."

Yes, I likely helped pay for your vaccine. I pay taxes, which I guess you don't.

Not only that Commenter_XY, but isn't it true that prior to authorization by the Constitution, no state had ever held a popular vote at all? And to this very moment, there has never been a national popular vote on anything. So what is your point? Do you want to join me in advocating an end to the electoral college?

lathrop, the question you pose is quite simple.

"...isn’t it true that prior to authorization by the Constitution, no state had ever held a popular vote at all?"

Answer: No, that is not true.

Did you mean: isn’t it true that prior to authorization by the Constitution, no state had ever held a popular vote on their representative form of government at all?

If that is what you meant, then you might want to look into RI, lathrop. Interesting historical aside: The RI state representatives were so incensed about the special conventions to ratify the constitution that they went home and specifically wrote a prohibition into their state constitution regarding constitutional conventions.

RI held out until 1790, when the Washington Administration threatened to start treating them like a foreign country (tariffs, closed borders and shipping zones). They grudgingly got together their own convention and approved the Constitution 32 - 30.

P.S. I saw Brett beat me to it.

RI (and of course, the People's Republic of NJ) has always interested me from the perspective of early American history. What an unusual cast of characters.

RI was first to declare independence from the crown on 5/4/1776

Conventions still has little or no meaning. I hate the use of the term in the Constitution. What exactly constitutes a convention? That is a term I would obliterate from the document and I have done so in my own rewrite to create an actual limited government: https://libertyseekingrebel.blogspot.com/2021/07/a-new-constitution.html?m=1

In fact, Rhode Island only ratified after being subjected to a naval blockade by the other states.

There are a lot of floor sweepings in the Constitutional sausage, once you start looking closely.

Brett, so why the deference to it? We both agree there are lots of floor sweepings in the process by which it was ratified. We both agree there are parts of it that have outlived their usefulness, even though we may not be in perfect agreement as to which parts. And we both agree that much of what was considered mainstream in 1789 is considered repulsive today. It strikes me that it requires more than a little masochism to force oneself to accept as binding the views of those who used much hanky-panky to give us an outdated document that no longer meets our needs.

That attude is espoused, outside ivory towers, by politicians who don't want pesky constitutions getting in the way of their self-defined growth jn power.

Dictators love the idea.

So, no. We have a way to give the government new powers it didn't have before, in a way that's noy easy the way dictators love.

That need will never expire, and those who squat on it for contemporary easy politics deserve every last Hitler, Stalin, Mao, or Saddam they get.

Examples of government growing its own power at its own whim: all of human history, a history of dictatorship and corruption, with rare, short-lived interstices of something remotely approaching freedom.

Krayt, the solution to that problem is regular elections and an independent judiciary. Saddam Hussein never had to run for re-election. Neither did Stalin or Mao. And none of them had an independent judiciary looking over their shoulder enforcing the bill of rights.

In fact, the USSR did hold regular elections. It's just that only one candidate was permitted for each office. Stalin famously said that it wasn't who voted that mattered, but instead who counted the votes, but their actual technique was controlling ballot access.

Stalin himself did stand for election twice; The first election he won due to, IIRC, all the competing candidates being killed, and the second was merely rigged.

My comment assumed free and fair elections.

Your comment assumes more than it should.

Do you think Stalin was not cognizant of big city machine machinations?

Of funky elections?

Of widespread bribery, corruption, and fraud coincident to, and in connection with, elections in the Anglosphere?

Assume a spherical cow....

The deference to it comes from several sources.

1) Every officer of the US government swears an oath to uphold and defend the US constitution. If they can't bear to do that, they should find some other line of work. If they're willing to swear that oath intending to break it, does this not speak to how far you should trust their word on absolutely anything?

This is a continuing theme of mine: Having a limited government constitution interpreted to allow leviathan government is NOT, functionally, the same as having a leviathan constitution with the same government. It's not the same because you need to staff it with people willing to be party to doing that, people who are comfortable with twisting the words of the law.

You're a fool if you think they'll only do it when doing it would be a good idea. You can't staff a government with people willing to traffic in lies, and expect honest government. This is, in fact, an advantage many other countries have over us: Where constitution and practice are in alignment, even if a constitution is less than ideal, honest governance is at least possible. It's not when they conflict.

2) The rule of law has a great deal of value, even where the law is less than optimal. It's extremely useful for people to be able to read the law, (And the Constitution IS law.) and know what to expect. It's extremely damaging for them to read that law, and observe that it's not being followed, even apart from the unpredictability.

3) Do not assume for a moment that, if we allow informal constitutional 'change', that those changes must be popular. The formal amendment process forces you to prove a change is widely popular. The informal process just requires suborning five guys in black robes.

There's an old joke in right-wing circles: "The Constitution has it's problems, sure, but it's better than what we have today." I think that's true. There are a lot of problems with the Constitution as written, but it is still better than what we are getting in its place.

“It’s extremely useful for people to be able to read the law, (And the Constitution IS law.) and know what to expect.”

This is completely in tension with originalist practice. Since it’s not simply

reading the constitution, it’s also diving into obscure old dictionaries and English legal treatises, law review articles about corpus linguistics, random samples of early practice, and the idiosyncratic interpretations of our-of-touch judges.

I mean your own view of the 8th amendment is confirmation of that. A normal person would read it and assume their government can’t authorize them to be tortured as punishment for a speeding violation. But you come out and say “Um ACKSUALLY, based on these obscure sources and my cherry-picked amateur reading of history, it only means a judge can’t order you to be tortured for speeding while the law is silent. The legislature can pass a law authorizing that and the executive can do whatever they want to you.”

I think you over-estimate the difficulty of reading the law. Sure, there are cases where the common meaning of words has shifted enough over 200 years that the average person might mistake the meaning of a clause of the constitution. ("Regulate" in the 2nd amendment, for instance, has nothing to do with regulatory agencies.)

But many of the divergences between practice and text are evident even by reference to a modern dictionary; The meaning of "all" or "no" haven't changed in 200 years, have they?

“I think you over-estimate the difficulty of reading the law.”

If it’s so easy, why are you consistently wrong about it?

*burn*

Brett, even, "all," and, "no," might change considerably, based on changes in contextual interpretation from one era to the next. It is not the dictionary definition of words which is most vulnerable to mis-interpretation. Contextual changes are trickier—and far more common—than word-meaning changes (and yet those too cause frequent misreadings).

Note especially, today's language context is far more a product of occurrences people experienced after the founding era, and prior to today, than it is a product of pre-founding era context. Yet that more-remote and more-limited pre-founding era context is the entire sum of historically permissible founding era interpretation. Accuracy demands that nothing later than that be smuggled in or inadvertently relied upon.

Note especially, you cannot interpret that more-limited context accurately if you are unaware of what it excluded. And it excluded the vast majority of what is most salient in modern-era thinking and language use—almost all the post-founding era occurrences which condition the way we think today.

Folks who read founding-era language while bringing to it modern contextual practice, repeatedly end up attributing to the founders meanings which seem outlandish in actual founding era context. If you take up the study of founding era documents with an eye to relating them to modern-day controversies, you will be frustrated no end to discover how often events lead historical figures to the very brink of some modern controversy, only to see them veer off in some other direction, never to return to give even slight reflection to what you considered most essential.

That happens because almost everything which we think of as most important in today's public life was literally impossible to think about likewise then. It happens because the historical predicate for that kind of thinking lies in our well-remembered past, but it lay in their inaccessible future. So with few exceptions, they never thought about those things at all. The only way to make it look as if they did share your thoughts, is to smuggle the contextual predicate for your thinking back into your own invented past, using your own present-minded language and context.

Of course, modern readers, unschooled as they are in both founding era social culture, and founding era language use, are doomed to apply modern context to everything. They have no choice, modern context is all they have. So inadvertent smuggling becomes commonplace, and goes unrecognized. The very notion is rejected with assertions such as, "The meaning of “all” or “no” haven’t changed in 200 years, have they?"

Your own repeated insistence on what you take to be the extremely limited nature of founding era government is an example of that kind of error. You persistently read founding era documents wrong, because your modern, more-egalitarian, present-minded context blinds you to meanings a more-authoritarian, more-class-based society did in fact read into its laws and constitutional interpretations. Those actual readings are proved not in the words and documents alone, but in demonstrable interpretations given to them at the time, such as in court cases, and especially lesser uncelebrated magistrate decisions, lesser-known journalism, correspondence, commercial records, and so many other sources known mainly to specialist scholars. You don't read that stuff, of course. Mostly, only academic historians read those kinds of sources.

Thus, like so many modern readers of history who dote on idealized over-arching interpretations, you seem to overlook the possibility that founding era language and law was meant to apply selectively among different classes of people, and apply differently—with either nuanced or decisive differences—according to regard for age, sex, property ownership, marital status, income source, social status and honor, government position, trade knowledge and practice, race, religious affiliation, indentured status, apprenticeship, political connection or tendency, community reputation, and undoubtedly other factors as well. It was an application of law and governance so fragmented and particularized that it defies modern categorization using modern political distinctions.

For example, if I had a nickel for every time I have seen a modern reader re-assert that founding era women could not vote—while overlooking that widowed women who owned property sometimes (and not rarely) could vote—I would have many more nickels. I mention that only as an example of one fertile source of contextual misreading. There are countless other misreading errors which flow from other particular founding era contextual peculiarities which go unnoticed in modern context. Only a few of those misreadings come from getting the dictionary meaning of words wrong. Not many of them can be sorted out by language sampling, as with corpus linguistics. Such contextual errors mostly come from combining too much reliance on present-minded language and context, with simultaneous ignorance of a bygone culture.

It is for that reason that devotees of the notion of useful history—with would-be originalists and ideological libertarians prominent among them—go so far astray. They could correct that tendency by actual historical scholarship—meaning a years-long study of original documents of all kinds from the historical eras they reference—but none of them seem to do it. Their interests lie elsewhere, apparently.

To be replaced by what, Krychek_2?

What do you propose replacing that outdated document with?

I think he is proposing reading broad terms in the document as a person today would read them and consistent with today’s values instead of some obscure originalist construction that makes the document meaningless to the modern reader and enforces the often odious values of the long-dead framers.

LTG (and Krycheck_2)...When I read, "The Constitution is wide open to interpretation, so interpret it in such a way that you don’t get awful results.", I had to chuckle. But I understand where you are headed wrt how to apply the Constitution to current questions (tho, one might say you're both headed to an awful result by changing the interpretative framework).

The two of you might not like my 'modern' interpretation of the Constitution to get a something other than a truly 'awful' result. 🙂

Basically what Law Talking Guy said. The Constitution is wide open to interpretation, so interpret it in such a way that you don't get awful results. Just because the framers didn't understand equal protection to include women or gays doesn't mean we can't understand equal protection to include women and gays. Just read the terms as we understand them today, not as James Madison would have understood them.

But there's no objective "awful results". There's just different people's opinions as to what's awful. If your only rule of interpretation is "read it as meaning something good", you're only pretending to have a constitution anymore.

If a document actually has a meaning, it can sometimes mean something you don't like, or even think awful, after all.

Seriously, there are no awful results? Jim Crow wasn't an awful result? The internment of Japanese Americans during WWII wasn't an awful result? If you're claiming that there is no such thing as objectively good or bad, then we just disagree.

There are no objective awful results.

In fact, Jim Crow is a perfect example of the interpretive standard you're espousing, being put into operation by people who had a different idea of "awful" results from yours. They warped the language of the Constitution to arrive at less awful results than blacks being free and equal. In their own subjective opinions!

Your problem here is that you're treating your own subjective opinions as though they were some kind of universal law, as though people who disagree with you don't really have a different idea of what's awful, but instead agree with you about awfulness, and just prefer awful.

No, people actually disagree with you about what is "awful", and nothing privileges your conception of it.

If a text, written by somebody who lived in a different culture and time, doesn't say some things you don't like, that would be really strange. But it still means things even if you don't like them!

Any mode of "interpretation" that can't arrive at meanings it doesn't like, isn't interpretation at all. Because sometimes things really do mean something you don't like.

"so interpret it in such a way that you don’t get awful results"

Too late! 60 years of such interpretation has resulted in a lot of awful results.

And an awful lot of great results.

Heller is one. Next?

I like how you sarcastically and sneeringly ask "next" as though one couldn't exist when Brown is literally right there. But I suspect you think that is an awful decision too.

So Bob, are you acknowledging that Heller is not an originalist decision and is in fact based on living constitutionalism (which is what we're discussing), albeit right-wing living constitutionalism? If so, that's progress.

Like Gonzales v Raich?

Reminder of what result Bob thinks is awful:

He would be quite happy if an indigent juvenile defendant with intellectual disabilities was arrested based on a warranties wiretap, subject to a coerced confession of engaging in sodomy, tried without an attorney because he was too poor to afford one, then sentenced to death for the offense with limited ability to appeal the sentence.

The constitution had 3 big mistakes, which are understandable. It did not end slavery, known to be wrong by anyone educated since the 1750's. That caused the Civil War.

It had a patent term that slowed innovation.

It had the lifetime appointment of the Supreme Court, but 100 years before Alzheimer described dementia. Normal aging is still devastating. It makes more physiological sense to appoint 16 year olds to the Court for intelligent and rapid decision making. End their terms at 40, when they become idiots. This mistake is a factor in the utter stupidity of most Supreme Court decisions.

(Say it takes 100 correct answers to get an IQ of 100. At 40, the age corrected requirement is 50 correct answers to get an IQ of 100 at 40. We are ruled by a retardocracy. Without correction for age, these Justices would qualify for Special Ed in high school.)

I think you missed a huge mistake: combining the head of state and head of government in the same office remains one of the biggest I corrected mistakes. I would suggest there are many others but IMO, this is the biggest outstanding mistake from the original document.

CORRECTION: ‘Uncorrected’ was edited into ‘I corrected’

I think the biggest mistake, in retrospect, was not specifying how Senators would be chosen, but instead leaving it up to the state legislatures.

The purpose of the House was to represent the population, and the Senate to represent the states as institutions. It was thought that the state legislature would pick somebody who'd do that effectively. Instead they got lazy, delegated the job to the voters, and you got two chambers that represented the population.

While as a matter of democratic theory, this might not have seemed a bad thing, in terms of the structural design of the Constitution it was disastrous. With the states as institutions deprived of any direct veto over judicial appointments or legislation, (As had originally been intended.) the natural tendency of the federal government to accumulate power was largely unchecked. It immediately began over-reaching its intended role.

With the ratification of the 17th amendment, the last theoretical check on federal power, the ability of the state legislatures to reclaim their control over the composition of the Senate, vanished. And that centralizing tendency shifted into high gear. Members of the judiciary were chosen on the basis of their willingness to permit power grabs. Senators no longer had to fear state legislatures, having a secure independent power base.

What they should have done was to have specified that the legislature itself appoint the Senator, not that the Senator be chosen in the manner the legislature dictated. Stick them unavoidably with the duty, leave them no way to give it away. Or, perhaps, create the Senate as a chamber of state Governors.

But anyway, make sure that Senators would actually represent the institutional interests of state governments, as originally intended.

Can we repeal the 16th amendment right after the 17th is repealed? Pretty please? 🙂

"combining the head of state and head of government in the same office remains one of the biggest I corrected mistakes"

Having an independent executive is one of the best things about the Constitution. Its a huge block against bad passion ridden majoritarian decisions.

I think he meant to say that there is a benefit in having a separate person being head of state, like a constitutional monarch. A figurehead outside the realm of politics that everyone can "pledge allegiance to". If the head of statse is also the chief executive, one runs the risk of being accused of being unpatriotic if one disagrees with him on a political issue. Anyone with memories of the Nixon Administration can tell you that this is a real danger.

"But whether the Constitution really be one thing, or another, this much is certain - that it has either authorized such a government as we have had, or has been powerless to prevent it. In either case, it is unfit to exist." - Lysander Spooner "No Treason VI, The Constitution of No Authority"

Let's hear it for Lysander Spooner.