The Volokh Conspiracy

Mostly law professors | Sometimes contrarian | Often libertarian | Always independent

Lakefront—Comparing Public Trust and Public Dedication

A right of private property—called the public dedication doctrine—rather than the public trust doctrine has been the successful device for preserving Chicago’s famous downtown lakefront park.

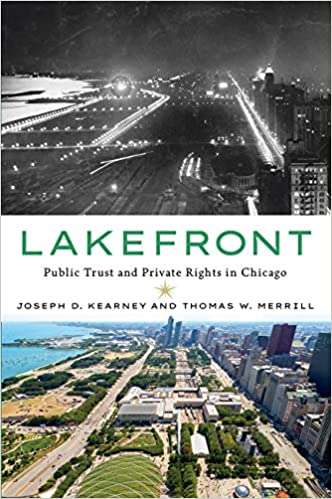

The public trust doctrine is frequently invoked by environmentalists and preservationists who want courts to block particular projects. The Chicago lakefront, its modern birthplace (as recounted in our inaugural post in this guest series), provides a kind of natural experiment for considering how well the public trust doctrine performs in realizing this preservationist ideal. As documented in our new book, Lakefront: Public Trust and Private Rights in Chicago (Cornell University Press), there were two competing doctrines, applicable to different segments of the Chicago lakefront. The public trust doctrine applies up and down the eastern front of the city, to land under (or once under) Lake Michigan.

In the center of the city's lakefront, in what is now called Grant Park, a different legal precept—called the public dedication doctrine—has been in play. It turns out that the public dedication doctrine has proved a more powerful form of protection against encroachment on public rights than the public trust doctrine.

The public dedication doctrine is a creature of equity. It holds that a private party who purchased property abutting land that is marked on some kind of public map or plat as being dedicated to a public use can sue to enjoin a deviation from that public use. In the case of downtown Chicago, lots were sold by early developers using maps that identified the area east of Michigan Avenue as being a "public ground for ever to remain vacant of buildings," or words to that effect.

Persons who bought lots on the west side of Michigan Avenue were willing to pay a premium for such a lot because it gave them a direct view of the lake. These purchasers could plausibly maintain that they had relied on the dedication appearing on the early maps and thus expected that their view of the lake would never be encumbered by the erection of "buildings."

The Michigan Avenue owners were not shy about acting to enforce their public dedication rights. In 1864, for example, they sued to block the Democratic Party from erecting a temporary "wigwam" in the dedicated area for the purpose of nominating General George B. McClellan as its candidate for president.

The most persistent litigant was Aaron Montgomery Ward, the catalog merchant, who brought or threatened to bring dozens of legal actions in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries against various proposed structures and activities in the protected area. His greatest triumph was to block the construction of the Field Museum of Natural History in the center of what is now Grant Park, which is why the museum had to be located outside of the dedicated area, to the south of the park, at what is now called Roosevelt Road. Popular though the Field Museum (or Soldier Field, to its immediate south) is, this is far enough from the commercial center of the city that most will not walk the distance.

Even after Ward's passing from the scene in 1913, the public dedication doctrine has been invoked by generations of Michigan Avenue owners to keep Grant Park largely free of encroachments. The only major exceptions, built more than 100 years apart, are the Art Institute and the whimsical structures of Millennium Park, in the northwest corner of the dedicated area. These were allowed based on representations (somewhat dubious in both cases) that they enjoyed the consent of all directly abutting property owners.

At times, the property owners have been overzealous. A new bandstand in Grant Park was blocked for years with threatened lawsuits, even after the old one was so decrepit that it caused a grand piano to fall through the stage. But it is undeniable that the 319-acre park in the center of the city is remarkably free of monumental structures. For which, the public dedication doctrine deserves the credit.

In theoretical terms, public dedication is rather the opposite of the public trust. Public dedication is designed to protect private rights—the right of owners to rely on dedications that enhance the value of their private property. The public trust doctrine is designed to protect public rights—the right of the public to use certain resources free of exclusion rights exercised by private property owners.

In practice, by harnessing the interests of private owners, the public dedication doctrine has proved to be the more powerful in protecting certain public interests: namely, the right of the public to enjoy the open space of a huge, centrally located, metropolitan park. It is worth pondering why this might be so. A primary factor concerns who has standing to sue.

The public trust doctrine in Illinois (this aspect of its development is among the things sketched out in our second post) can be enforced either by the attorney general or by any taxpayer. In practice, this means that either one faction of the political establishment must sue to block what another faction of the political establishment wants to do, or a coalition of taxpayers must form that has sufficient funding and unity of purpose to oppose what the (often-united) political establishment wants to do. These conditions will not always be satisfied.

The public dedication doctrine, by contrast, can be enforced by any private property owner whose land abuts a dedicated space and who believes that what the political establishment wants to do will devalue his or her property more than it will cost him or her to sue. At least for major deviations from the dedication, this may elicit a more consistent enforcement of public rights than does the public trust doctrine.

The major weakness of the public dedication doctrine is that there must be a dedication, whether it be for a park, or an open space free of buildings, or something else. The area that comprises Grant Park was favored with such a dedication. Other areas up and down the lakefront were not. Hence, we see a more checkered pattern of protection of public rights outside the center of the city, especially when projects are proposed that have the strong support of the political establishment.

As we shall see in our fourth (and penultimate) post, the Illinois Supreme Court repudiated the common-law public dedication doctrine in 1970, casting its lot exclusively with the public trust doctrine. In our view, this was a mistake. Often, harnessing private rights can do more to protect the public interest than can a more overtly public-sounding doctrine.

Show Comments (4)