The Volokh Conspiracy

Mostly law professors | Sometimes contrarian | Often libertarian | Always independent

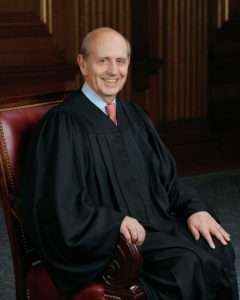

Justice Breyer Warns Against Court-Packing

In this he echoes a number of other liberals, including the late Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg.

In a recent virtual speech at Harvard Law School, liberal Supreme Court Justice warned against efforts to "pack" the Supreme Court in order to eliminate the current 6-3 conservative majority:

In a speech at Harvard Law School on Tuesday, Breyer said that the court's authority depends on "a trust that the court is guided by legal principle, not politics."

He added: "Structural alteration motivated by the perception of political influence can only feed that latter perception, further eroding that trust."

On this point, Breyer echoed the late Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg, who spoke out against court-packing even more forcefully in 2019:

"Nine seems to be a good number. It's been that way for a long time," she said, adding, "I think it was a bad idea when President Franklin Roosevelt tried to pack the court…"

Roosevelt's proposal would have given him six additional Supreme Court appointments, expanding the court to 15 members. And Ginsburg sees any similar plan as very damaging to the court and the country.

"If anything would make the court look partisan," she said, "it would be that — one side saying, 'When we're in power, we're going to enlarge the number of judges, so we would have more people who would vote the way we want them to.' "

That impairs the idea of an independent judiciary, she said.

Ginsburg's fear that court-packing would undermine judicial independence and, thus, judicial review) strikes me as a more compelling concern than Breyer's worry that it would merely erode public confidence in the Court, though the two issues are obviously connected.

Breyer's critique of court-packing - like Ginsburg's before him - could potentially be dismissed as biased by self-interest. After all, any expansion of the size of the Court necessarily diminishes the influence of current Supreme Court justices. On average, a single justice on court with eleven or fifteen members has less clout than if the court's membership remains at nine.

But, in Breyer's case, such self-interested bias probably is not a major factor. The scuttlebutt in legal circles suggests he may well retire this year, in order to give Biden a chance to appoint a liberal successor while the Democrats still constrain the Senate. That, certainly, is what many liberals want him to do. Even if he chooses to stay on longer, Breyer surely knows that, at the age of 82, he probably does not have many more years left to serve. Thus, concern for his personal influence is unlikely to be the key factor in his opposition to court-packing.

Ginsburg and Breyer are far from the only prominent left-of-center critics of court-packing. I noted some other examples here.

I have written about the dangers of court-packing in greater detail here, here, here, and here, including addressing claims that it is an appropriate response to Republican skullduggery in the judicial nomination process, such as their hypocrisy in refusing to vote on a nomination in an election year in 2016, while pushing one through quickly just before the 2020 election. I also opposed an abortive conservative proposal to pack the lower courts back in 2017, which occasioned my first foray into this issue.

For reasons I summarized in January, it is unlikely that the Biden administration will push for court-packing in the near future, or that it can pass Congress even if Biden does make such a push. But, as explained in that same post, the idea has become a part of mainstream politics, and is unlikely to fully go away for some time to come.

Editor's Note: We invite comments and request that they be civil and on-topic. We do not moderate or assume any responsibility for comments, which are owned by the readers who post them. Comments do not represent the views of Reason.com or Reason Foundation. We reserve the right to delete any comment for any reason at any time. Comments may only be edited within 5 minutes of posting. Report abuses.

Please to post comments

If the Supreme Court will be making laws, cancelling laws, make the size of a legislature, 500 Justices. Exclude anyone who has passed 1L to raise its IQ from its current dumbass level, slower than a kid in Life Skills Class, learning to eat with a spoon. Move its location to a small government supporting jurisdiction. Make the Justices impeachable by Congress for their decisions. Limit their terms to 20 years. Past 80, some kind of dementia testing should be required. Make the number an even number to avoid 5-4 decisions that brind opprobrium on the Court. An even number would preserve their own precedents.

These healthy goals may be achieved with a new Judiciary Act, save for the change in term.

JOB FOR USA Making money online more than 15$ just by doing simple work from home. I have received $18376 last month. Its an easy and simple job to do and its earnings are much better than vvvc regular office job and even a little child can do this and earns money. Everybody must try this job by just use the info

on this page.....VISIT HERE

JOB FOR USA Making money online more than 15$ just by doing simple work from home. I have received $18376 last month. Its an easy and simple job to do and its earnings are much better fg than regular office job and even a little child can do this and earns money. Everybody must try this job by just use the info

on this page.....VISIT HERE

When scholars actively propose "deals" to avoid court packing, it's inevitable that court packing will become part of the mainstream politics, and a potential option.

When something (like court packing) isn't an option, it can't be used as leverage for such a "deal". The very concept of proposing a deal legitimizes the potential for court packing if the "deal" fails.

Breyer said that the court's authority depends on "a trust that the court is guided by legal principle, not politics."

Right. Clear evidence in regard to this is, that with rare exception, all media outlets (left, right, center) always mention the name of who appointed the judge right after mentioning the judge. They know that almost nobody has confidence that conduct and decisions on hot issues are not decided on politics.

I am not sure that expanding the court from 9-to-whatever would fix this. I don't see how it would make it worse either.

In theory it should make it worse, because (rational) people are aware that, on a divided Court, principle can sway the Justice at the margin, but if you stack the Court so that the Justice at the margin is a devoted partisan, forget principle.

The thing is, with bills like HR1 the Democrats are guaranteed to never go out of power. So, the claim that "when we're in power we'll just add more judges [right back]" are meaningless as Republicans won't be allowed back in power.

If you pack the Court the Constitution can mean whatever you want it to. Molded like Play-doh to whatever shape is politically expedient.

I disagree that Republicans could not regain power.

They would need to ditch the bigotry, superstition, and backwardness to accomplish that, though.

Whether they improve before they are replaced should be an interesting development to observe.

Could you be a bit more specific about what a Republican Party platform would look like in Kirkland-land?

Maybe there's a chance to reach across the aisle here.

I'm beginning to suspect I was being a bit optimistic.

Ever see that episode of Futurama where the presidential candidates were literal clones of each other named John Jackson and Jack Johnson? I suspect it would be like that

I recall a Republican Party that prized education, competence, reason, science, progress, modernity, and to some degree tolerance and limited government.

Those Republicans wanted America to improve. Those Republicans wanted America's government to be effective and efficient.

Their party was not mired in low-grade bigotry, old-timey superstition, and belligerent ignorance.

Their party was a worthwhile organization with many decent, admirable members.

I'm sure that's what you told yourself during the Obama years.

Artie, Trump came close if not outright won, despite the intentional devastation of the economy and of the stock market by Democrat governor mass killers. After the agonies of the voter, Trump will be right back in 2024. We are sick of you Commies already. Cancel will visit all PC, all Commies, all America hater traitors. Then, we have to crush the lawyer profession, the most toxic occupation in the country, 10 times more toxic than organized crime.

Hollow bluster from all-talk culture war losers is fine entertainment -- and the core of the Volokh Conspiracy.

I keep making this point: You can't analyze Court packing in isolation, it's an early step in a combo finishing move.

First you get rid of the filibuster.

Then you pack the Court.

Then you start enacting unconstitutional entrenchment legislation an unpacked Court would have struck down.

Probably somewhere along the line you start expelling members of the opposition from their seats. (Likely after packing the Court; Once you've done that, there's no turning back, might as well be hung for a sheep as for a lamb.) Democrats in Congress have been discussing doing this, though it gets less attention than the Court packing threats.

See, for instance: Joe Manchin Backs Congress Considering Removal of Ted Cruz, Josh Hawley Over Capitol Insurrection

Breyer is trying to lock the barn after the horse has been stolen. By now we've all heard the tale from a Court staff member of how Chief Roberts insisted on not taking up Trump's election cases: "We weren't facing RIOTS in 2000!!"

I submit that a court which grants terrorist groups a rioter's veto makes a politically biased court look tame. As well as giving the side that doesn't do riots a seriously strong incentive to start.

By now we’ve all heard the tale from a Court staff member of how Chief Roberts insisted on not taking up Trump’s election cases: “We weren’t facing RIOTS in 2000!!”

Utter nonsense, clear the moment it started making the rounds. You can't overhear people who are not meeting in person.

" You can’t overhear people who are not meeting in person."

You're going with something that silly? I overhear people who are not meeting in person any time somebody the next cubical over has a zoom conference on speaker.

"he may well retire this year, in order to give Biden a chance to appoint a liberal successor while the Democrats still constrain the Senate. "

But we wouldn't want to 'politicize' the Court, would we?

There are 13 circuits. There should be 13 supreme court members.

(And of course the circuit populations and legal loads should be rebalanced).

Good luck getting there from here in any reasonable way.

It could be easier than most people recognize.