The Volokh Conspiracy

Mostly law professors | Sometimes contrarian | Often libertarian | Always independent

Four Thousand Years Ago, Textile Traders Invented a Basic Social Technology: Mass Literacy

When there's business to be done over long distances, you don't want to depend on a scribe.

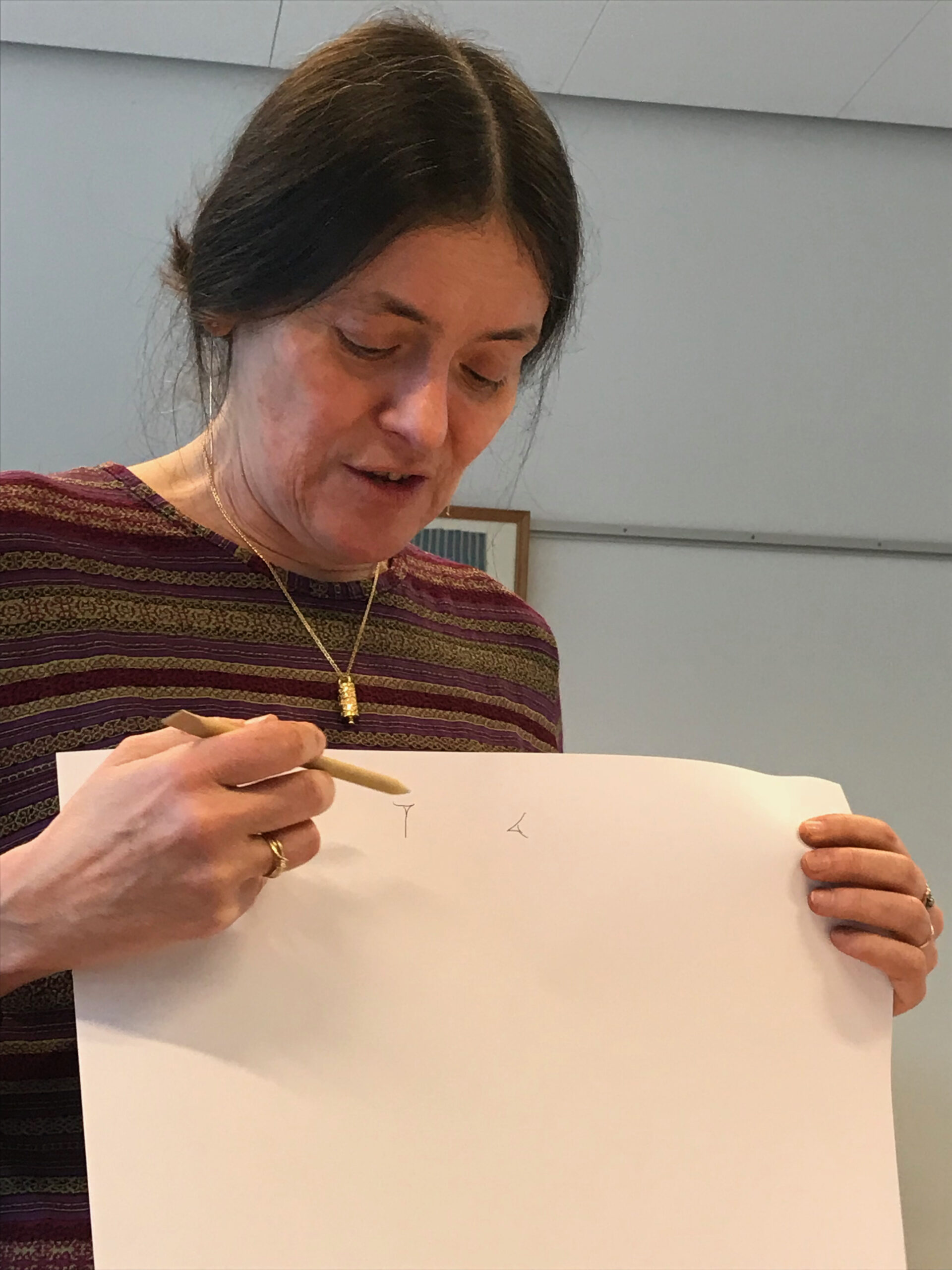

One of the many interesting scholars I met while researching The Fabric of Civilization was Cécile Michele, a French Assyriologist who has translated many of the 23,000 cuneiform tablets excavated from a site in Turkey. Here she is teaching us the basics of how to write in cuneiform.

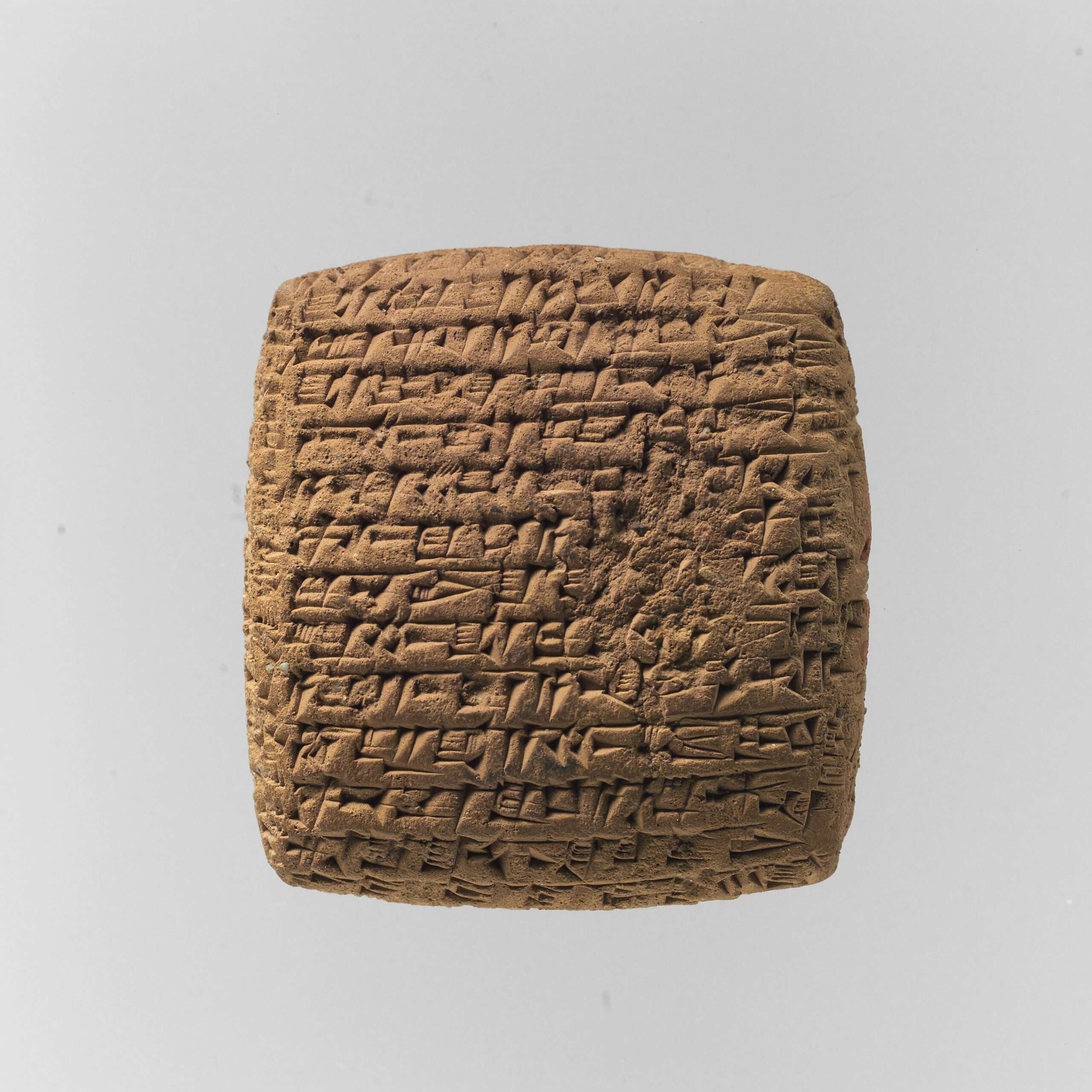

The tablets, known as the Old Assyrian private archives, are about 4,000 years old. They were found in the homes of expatriate merchants in the city of Kanesh, now the archaeological site called Kültepe. These letters and legal documents preserve the practices and personalities of a thriving commercial culture. They are our oldest records of long-distance trade.

Capturing dilemmas and decisions still faced by commercial businesses, these ancient records testify to the central role of textiles in the innovations that enable economic exchange. Here, the inventions aren't material artifacts or physical processes but "social technologies": the records, agreements, laws, practices, and standards that foster trust, ameliorate risks, and allow transactions across time and distance. Four millennia later, we can still hear the voices they record.

Lamassī was doing her best to keep up with the demand for her fine woolen cloth, fickle though the requirements seemed to be. First her husband asked for less wool in the fabric, and then he asked for more. Why couldn't he make up his mind? Maybe it was his customers in that distant country. Maybe they didn't know what they wanted. At any rate, her latest batch of cloth, or most of it, would soon be on its way. She wanted Pūsu-kēn to know it was coming. She wanted him to know she was doing her job. She wanted a little appreciation.

Lamassī rolled a small ball of damp clay between her hands, then flattened and smoothed it into a neat, pillow-shaped tablet, which she cupped in her left palm. She picked up her stylus and began to write, pressing wedge-like characters into the wet clay.

Say to Pūsu-kēn, thus says Lamassī

Kulumāya is bringing you nine textiles. Iddin-Sîn is bringing you three textiles. Ela refused to take any textiles and Iddin-Sîn refused to take another five textiles.

Why do you always write to me, "The textiles that you send me each time aren't good!" Who is this person living in your house and denigrating the cloth that I send to you? For my part, I do my best to make and send you textiles so that for every trip at least ten shekels of silver can reach your house.

Her message completed, Lamassī dried the tablet in the sun. She then wrapped it in a gauzy fabric, which she coated with a thin layer of clay. She ran a cylindrical seal along the clay envelope to mark the letter as hers. A messenger would take it to her husband, 750 miles away in the Anatolian city of Kanesh.

Lamassī lived in Aššur, on the Tigris river near Mosul in modern-day Iraq. It was a city of middlemen who purchased tin and textiles and exported them, along with their women's weaving, to Kanesh. Twice a year, caravans of donkeys made the six-week journey. A single caravan might include wares from eight different merchants, with thirty-five donkeys carrying more than a hundred pieces of cloth and two tons of tin. Some of the wares went for taxes in the two cities and in kingdoms along the way that guaranteed safe passage. The rest were traded for silver and gold.

By the time Lamassī picked up her stylus, cuneiform script was a thousand years old. For most of that time, however, writing had been the monopoly of a small class of specially trained scribes, probably a mere one percent of the population. Throughout most of human history, in fact, literacy belonged to the few, mostly men working for state or religious institutions.

Not so in Aššur.

For its people, letters were a critical technology. They needed to send instructions between Aššur and Kanesh and between Kanesh and the surrounding towns, where their agents sold textiles and tin. They needed to record orders, sales, loans, and other contracts. They needed the flexibility and control that come with literacy.

Over time, these pragmatic merchants simplified the cuneiform script, making it easier to learn and write. They invented new punctuation that let them skim documents quickly. Some wrote well, others poorly. But in this society of long-distance traders, most men and many women were literate.

Trade requires clear communication, particularly if the business owner doesn't conduct every negotiation personally. Consider Pūsu-kēn. He first went to Kanesh as the agent of an older merchant in Aššur and, even as his own ventures grew, he continued to work on behalf of various traders back home. When their textiles and tin arrived in Kanesh, he needed to know what to do with the goods. Should he sell them in the city's marketplace, sacrificing profits for immediate cash? Or should he seek a higher price by selling them on credit to an agent who worked the outlying towns? Letters came with the goods, telling him what to do.

Letters are such an old technology that we take them for granted. But they were crucial to long-distance trade. When commerce stretched over time and distance, written correspondence—and the literacy it required—came with it.

Editor's Note: We invite comments and request that they be civil and on-topic. We do not moderate or assume any responsibility for comments, which are owned by the readers who post them. Comments do not represent the views of Reason.com or Reason Foundation. We reserve the right to delete any comment for any reason at any time. Comments may only be edited within 5 minutes of posting. Report abuses.

Please to post comments

Text on tiles . . . textiles

I liked the way she wove those seemingly disparate threads together.

Interacting with a scribe can be complicated! This one, for instance:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=X7JUbJWSKrY&t=9m28s

It seems to me that all kinds of traders, not just textile traders, would develop literacy for these reasons.

Was the textile trade particularly complex, involving different fabrics, designs, etc., so that there was more need for detailed instructions?

What else was there -- animals, food, pottery, weapons? I doubt the others had as many variations as textiles.

Spices.

I had that under food. Unless there was takeout, I doubt food could vary like textiles.

Where did this come from? It is near-certainly false; the odds are overwhelming that Lamassī was illiterate. The salutation of the letter, "Say to Pūsu-kēn, thus says Lamassī", is obviously conventional, but it immediately tells you that the recipient is not expected to be able to read it -- it starts with an explicit instruction to the scribe who can!

That's probably no more instructions than any other idiom. "Your humble servant" does not refer to any scribe who wrote down dictation.

This is a translation from a long-dead language with lots of guesswork. Taking it literally is impossible.

That just gets you from proof Lamassi was illiterate, to it merely being possible. You'd have to establish whether lines like that were meant literally, or were idiom. You can't just assume idiom.

More recent examples of illiterates dictating letters, or having letters to them, such as from the American Civil War, show letters written as if neither party was illiterate. Maybe that is just a language construction. In English, we say "He said he wouldn't go", whereas Japanese are more prone to literal quoting, "He said "I won't go"". Who knows how this language handled such things, or whether written and spoken differed.

Agree w/ Alphabet Soup, the salutation could well be a holdover from days when scribes at each end were more common.

(For this text only I unsheathed my stylus from my LG phone, which yes I'm cupping in my left palm:-) ).

"is obviously conventional, but it immediately tells you that the recipient is not expected to be able to read it"

A reasonable conclusion as far as it goes, but based on the salutation, Lamassi is the sender, not the recipient, so your conclusion that Lamassi was most likely illiterate is fatally flawed.

Come on. You talk as if I was presenting evidence. That's not necessary; the conclusion would be just as strong if I hadn't mentioned the salutation at all. We know a good amount about this society, and we know that almost nobody was literate.

I gave an example showing the assumption of widespread illiteracy within the society.

"I gave an example showing the assumption of widespread illiteracy within the society."

No, you didn't.

That would only mean that Pūsu-kēn was illiterate, or at least had someone to read his letters to him. It doesn't tell us anything about Lamassī. How would you expect it to read differently if she wrote it herself? Maybe writing was women's work, like spinning and weaving were.

I recently saw the case made that literacy in the Middle Ages was far more common than we originally thought -- that there was likely at least one per household that could read. Being able to read and write is just too useful a skill to leave unlearned.

The funny thing is, though, people at the time were described as "illiterate" if they couldn't read or write Latin -- which was something that was limited to scholars, scribes, and the clergy.

So I'm not surprised that cuneiform was more commonly learned that we previously thought!

Just wanted to say I have enjoyed these articles on textiles and literacy. Certainly a nice change of pace from politics.

I am very amazed while reading this. We also do the global export of textiles, but the ancient civilization was doing trade is very surprising. Thanks for sharing this wonderful article.

Regards,

Faze Three Limited