The Volokh Conspiracy

Mostly law professors | Sometimes contrarian | Often libertarian | Always independent

Stare Decisis is an Old Latin Phrase that Means "Let the Decisions of the Warren Court Stand"

Halfway Stare Decisis, like Halfway Textualism, Allows the Court to be Ruled by the Dead Hand of William Brennan.

Superficially, Bostock may seem like a triumph for textualism. It wasn't. Rather, Justice Gorsuch built a textualist edifice on top of non-textualist precedents from decades ago. His understanding of Title VII was governed by Justice Brennan's plurality decision in Price Waterhouse v. Hopkins (1989). Randy Barnett and I called this approach "halfway textualism." Going forward, judges should reconsider the relationship between textualism and statutory stare decisis: to what extent is a textualist analysis governed by precedents that disregarded textualism. Alas, Justice Gorsuch completely missed this issue.

Judges should also consider a closely related issue: the relationship between originalism and constitutional stare decisis. For argument's sake, I'll assume that statutory stare decisis differs from constitutional stare decisis. In theory, at least, if the Supreme Court interprets Title VII incorrectly, then Congress can amend the statute. (Congress revised Title VII in response to Justice Brennan's Price Waterhouse plurality). In contrast, amending the Constitution is much more difficult. Justice Thomas sees no reason to follow constitutional stare decisis. But he is alone on the Court.

As a result, the Justices are constantly binding themselves to precedent, even where that precedent is utterly inconsistent with the original meaning of the Constitution--and even where those later-in-time precedents reversed earlier, better decisions!

Let's consider a straightforward example. In Wolf v. Colorado (1949), the Supreme Court held that the states were not bound by the so-called exclusionary rule. Twelve years later, Mapp v. Ohio (1961) reversed Weeks. Now the states were bound by the exclusionary rule. What should a future Court do? Stand by the decision of the Vinson Court in Wolf? Or stand by the precedent of the Warren Court in Mapp? With halfway stare decisis means, you stand by the latter precedent, even if the former precedent was correct as an original matter.

Consider another example where the Court sets a new precedent. Griswold v. Connecticut (1965) held that the Constitution protects a right to privacy, and Connecticut's prohibition on married couples using birth control was unconstitutional. The ruling was based on a bizarre analysis of penumbras and emanations from the Bill of Rights:

I don't think anyone will defend its reasoning today.

Griswold did not overrule any precedents, though it was flatly inconsistent with Footnote Four of Carolene Products. In time, Griswold begat Eisenstadt v. Baird, which begat Roe v. Wade, which begat Casey, which begat Whole Woman's Health, which begat June Medical, and so on. But the root of that doctrine is an indefensible decision. Yet, we are forever bound by the excesses of the Warren Court, because they were the first movers.

Adrian Vermeule describes this dynamic well:

If the very first decision freezes the law forever, obliging all subsequent Justices to put aside their disagreements permanently in the name of stare decisis, then the "bank and capital of nations and of ages" shrinks radically. The only depositors to the bank will be the Justices in the initial majority, which means in practice that a majority of only one or two will frequently determine the law forevermore.

On the Roberts Court, Stare Decisis is an old Latin phrase that means "Let the Decisions of the Warren Court Stand."

Vermeule writes further:

From a Burkean standpoint, it is breathtaking epistemological arrogance to think that one or two Justices, deciding at a single time under conditions of sharply limited information, should be able to determine the permanent course of the law.

Forevermore, we are governed by the dead hands of William O. Douglas and William Brennan. (Forget the dead hands of Madison and Hamilton--those hands are too dead!)

Vermeule continues:

But the effect of the Chief's approach is to require Burkean Justices to conform to the initial, maximally arrogant decision; conversely, more information would be contributed to the stock of epistemic capital if later Justices treated the second or subsequent case as one of first impression. The self-undermining approach of the Chief's concurrence, then, actually embodies a kind of judicial hubris cloaked in the garb of humility. (I will leave it to other commentators to speculate about why a veneer of humility seems so often to appeal to the Chief Justice).

In short, the Chief's judicial humility requires standing by decisions that he thinks lack humility. But only some of those decisions. Roberts will stand by Planned Parenthood v. Casey, but will not stand by Whole Woman's Health. In the future, I suspect he will stand by Grutter v. Bollinger, but will not stand by Fisher v. University of Texas, Austin II. And so on.

We should acknowledge the contradiction of halfway stare decisis.

Editor's Note: We invite comments and request that they be civil and on-topic. We do not moderate or assume any responsibility for comments, which are owned by the readers who post them. Comments do not represent the views of Reason.com or Reason Foundation. We reserve the right to delete any comment for any reason at any time. Comments may only be edited within 5 minutes of posting. Report abuses.

Please to post comments

IANAL. I have always thought it was reasonable for lower courts to give more weight to decisions from higher courts, otherwise things would slow to a crawl, you'd have judges differing all over the place, and people would judge-shop like there's no tomorrow.

But I have never understood stare decisis except as a way to adopt a previous result without having to show your work. It's like little Johnny copy little Sally's homework -- his excuse to the teacher is that she's already done the work, why should he do it again?

Screw that! Judges ought to start from fundamentals every single time, every single decision. Or as the teacher would say, "Show your work!"

I agree with the first bit. Lesser critturs should obey greater critturs, else there would be chaos. Or more chaos.

And in theory, there's value in SCOTUS following its own precedents, at least on matters that a reasonable and fair minded person would accept could have bounced either way. Particularly so for statute where it's easy enough - in theory - for Congress to tidy up.

But the difficulty is, they all cheat all the time. And we know they're going to cheat when it's convenient, and they can't be dismissed from the field. So what's the point of having the rule ?

To be fair it obviously a very human temptation, because Blackman himself does it within just a few sentences :

1. "halfway stare decisis means, you stand by the latter precedent, even if the former precedent was correct as an original matter."

2. "Yet, we are forever bound by the excesses of the Warren Court, because they were the first movers."

As one commenter on here said a day or two ago - I forget who - "stare decisis" is Latin for "when convenient."

This is far too cynical a view. For all of the paradoxes connected to stare decisis, it performs a vital function: It lends predictability to the contours of the law. It's not inviolate; the Supreme Court has overturned past decisions, but is rightly reluctant to do so.

To toss out stare decisis because you don't agree with the jurisprudential foundations of this or that line of cases is also to toss out history, logic, and continuity. Do you really want the Supreme Court to be a kind of roulette wheel? I don't.

100%. But it is tough because stare decisis is not always followed, it's not completely binding. No one would seriously say the Supreme Court must be totally bound by every prior opinion they issued, that's stasis, not stare decisis. So when do you follow it, and when do you not? So it's still confusing.

Casey goes into some details about the limits of Stare.

I'm not a lawyer. Only an honest man, or someone who tries to be. As far as I know, there's no set doctrine with respect to overruling earlier decisions. I simply observe that, a) It's been done, and more than a few times, and b) It usually takes a long time. The only instance I'm aware of to the contrary happened in the 1940s, when the Supreme Court overruled itself within a couple of years on the question of whether a school student could be required to stand for (or maybe recite, I forget) the Pledge of Allegiance.

I really don't want to see the Supreme Court turned into any more of a pingpong match that it already is. It ought to be somewhat responsive to political consensus, but if it flits back and forth in rapid fashion, it will quickly lose its credibility.

Yes, I realize that there wind up being paradoxes, and that decisions I might disagree with wind up surviving. I'd rather endure that than see the Court turn itself into a weathervane.

Yes, and no. There are two types of predictablity:

1) If you have a legal education, covering all past decisions, can you predict the outcome?

2) If you've just read the Constitution and the laws, could you predict the outcome?

Precedent is good for the first sort of predictability, bad for the second, because it preserves decisions that visibly got it wrong, maybe were just making shit up as they went along. Like "substantive due process" vs incorporation via P&I. If all you knew was the Congressional debate and the text of the 14th amendment, "substantive due process" would totally blindside you, because it's just a BS workaround to avoid ruling that the Slaughterhouse cases were wrong.

Since the Founding, the Constitution has not been predictable.

The problem here is not stare decisis, the problem is that the decision went against the personal preferences of the persons who have written so far.

The CJ did a courageous, principled thing in the best traditions of conservatism and respect for law. Once the Texas decision was decided it was important for the rule of law that consistency be maintained. A Court that changes the law every several years to meet the policy demands of the Justices is not a Court that generates respect for law, a respect that is desperately needed if the rule of law and respect of law is to be maintained.

The four dissenting Justices, Thomas in particular see their positions as a means to inflict their views on society. Every Justice does this to some degree. The CJ has prevented Thomas et. al. from going to the extreme.

"The four dissenting Justices, Thomas in particular see their positions as a means to inflict their views on society. Every Justice does this to some degree. The CJ has prevented Thomas et. al. from going to the extreme."

When the Court inserted itself into this area of the culture war (with zero constitutional or historical basis) it was inflicting its views on society. Thomas and co. would allow for pluralism (each state to determine its own course)

Your thought process produces a perverse asymmetry. One Court majority can create a new right out of whole-cloth via 'substantive due process'. That majority zealously guards their baseless arrogation of power. Those who recognize it for what it is are asked to leave it untouched lest they be accused of extremism

I agree with you(emanate in my pneumbra). Plus this protects Josh's beloved rights too. He loves the Espinoza decision and the 2nd amendment decisions. Unless a significant change occurs in the future, courts will use stare decisis as reasoning to uphold those holdings.

yet, that doesn't mean a future court won't chip away at the strength of the two decisions. This happens both ways. Casey was an example of chipping away at a prior decision.

I do think that the court needs to make an outline of what they will consider when overturning precedent. Justice Stevens created one, but it never got a 5 vote majority to become the test.

Oh, Justice Thomas would allow for each state to determine its own course?

Then I must have misread the Montana decision where he voted to over-rule the citizens of Montana, the legislature, the state constitution of Montana and its Supreme Court and denied Montana the right to not fund religious schools under the mistaken guise that this somehow violated the freedom of religion when of course freedom of religion does not and never has said government must subsidize private religious schools.

But he wouldn't rule that freedom of religion means that government must subsidize private religious schools. He'd rule that government must subsidize private religious schools if it is subsidizing private secular schools, and the religious schools meet the same criteria.

Which is not at all the same thing.

He reinstated the program passed by the Montana Legislature, which the Montana Supreme Court had overturned.

Are you suggesting that states can ignore the First Amendment?

No, I am suggesting that freedom of religion does not require those who believe in Religion A to subsidize Religion B and that not having taxpayers pay for education of Religion B does not in any way restrict those who want to worship in Religion B from doing so.

Don't see why this is a difficult concept for a lot of people who post on this Forum.

Your "argument" is difficult for people to understand, because that's not what the Montana case was about.

Yes, we are very much governed by the haphazard results-based Constitutional decisionmaking of the Warren and Burger courts. Much of it was correct, little of it was consistent. Smoothing out these things into coherent legal doctrines, dispensing with the indefensible or clear contradictions has been much of the work for the past forty years. It’s okay Josh, liberty is a good thing. I’d rather be ruled by the dead hand of Bill Brennan than the live hand of Adrian Vermeule.

I would prefer the dead hand of Brennan than the dead hand of Scalia.

The ruling was based on a bizarre analysis of penumbras and emanations from the Bill of Rights:

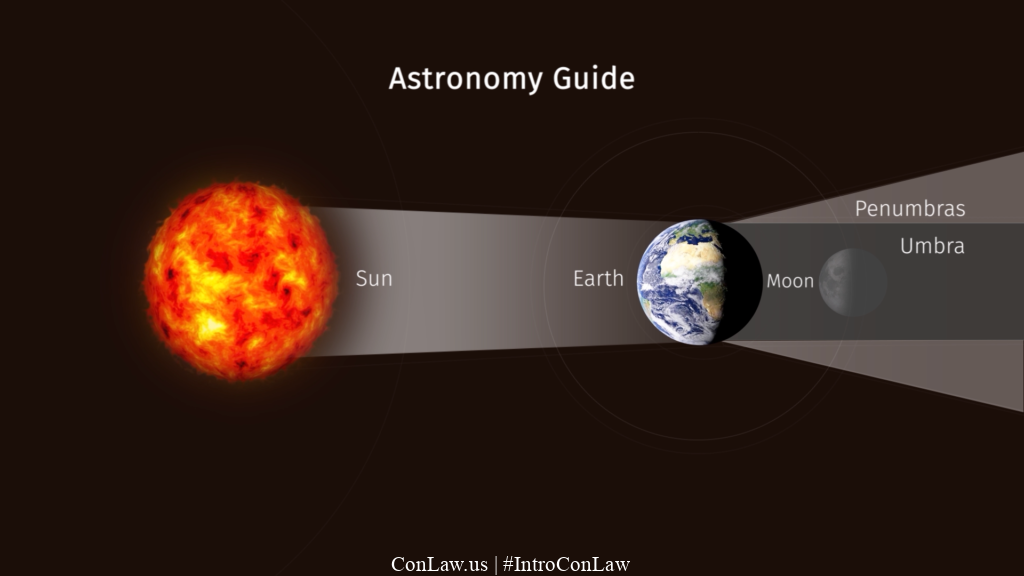

"Specific guarantees in the Bill of Rights have penumbras, formed by emanations from those guarantees that help give them life and substance." An "emanation" refers to a ray of light. During a lunar eclipse, the "umbra" refers to the darkest part of the shadow formed when the Earth orbits between the sun and the moon. The "penumbra" refers to the lighter part of the shadow, where some of the "emanations" from the sun are visible.

I don't think anyone will defend its reasoning today.

You live in a pampered conservative bubble if you really think that.

Why don't you get out into the world? You're not even 40 and you've never had a real life, except being in a pampered environment, law school, clerkship, now a law professor.

Besides pure vituperation, do you have an argument as to why one should take penumbras+emanations seriously?

In respect of Griswold, it seems simple.

The right to privacy is something that is in a good list of enumerated rights.

The Bill of Rights is a good list of enumerated rights.

Therefore the Bill of Rights must contain a right to privacy.

Since I can't see it directly, it must be in a penumbra and emanation.

There is no explicit right to privacy in the Constitution, except in the Fourth Amendment which applies only to searches and seizures, not to statutes per se.

Nobody is about to overrule Griswold. Douglas found the best possible reason and nobody has found a better one.

Because the 9th Amendment isn't meaningless.

Wait the exclusionary rule example is bad and off base. First Wolf v. Colorado did involve the court not applying the exclusionary rule as required by the 4th amendment. Yet earlier in WEEKS the court had said that the exclusionary rule was applicable to the federal government because of the 4th amendment. Therefore, if the right was incorporated shouldn't the same rule apply to the states?

Now if we apply regular constitutional law, the correct thing to do would be to have the criminal case go forward the defendant would be convicted. Then the defendant would appeal for a violation of his rights and the court would strike down the conviction and double jeopardy would attach. This would be a more disastrous result than the exclusionary rule.

Also to all who say the Warren Court went first. Remember courts abided by Plessy a decision done by an earlier conservative court and to this day abides by slaughterhouse a decision by the same earlier conservative court.

"First Wolf v. Colorado did involve the court not applying the exclusionary rule as required by the 4th amendment. "

You start out wrong: The 4th amendment doesn't mention any exclusionary rule: Rather than saying you can't use evidence obtained improperly, it says you can't obtain evidence improperly.

Surely the exclusionary rule is just modus tollens.

You cannot obtain evidence improperly

This was obtained improperly

Therefore this is not evidence

This kind of whiny radicalism is not the voice of someone who thinks they will eventually win anyone over with their arguments.

It asks for a rule of men not laws.

Josh is losing it.

Assuming he ever had it.

...Or he's at the forefront a new cynical conservative legal wave that thinks like they imagine liberals do.

Yup. He's trading Neil Gorsuch for Bob from Ohio.

IANAL either, but I have been following the actions of the Court with increasing skepticism all my life. It seems to me that when someone talking about candidates for seats on the Court praises "stare decisis", it is a code word meaning "don't even try appointing anyone who will overrule the Courts illegitimate precedents." (Meaning the ones where the Court was coerced into disregarding the Constitution to "save nine," starting in the New Deal years.)

If the court will not overrule those precedents, then it is time to hold a new Constitutional convention, because the Constitution we have has so failed to do its job that all the people can do is to exercise our power to revoke it and adopt a new one, as discussed in Paine's "Rights of Man."

Dred Scott

Plessy

Korematsu

All should stand because of Stare Decisis?

Of those three, only Plessy was overturned.

Brown is a great example of how you revisit a case and overcome Stare.

This post is a great example of outcome oriented how not to do that.

Korematsu was overturned in Trump v. Hawaii.

Thanks, I see that it was.

I'll ask again: what is your basis for this claim? Gorsuch's opinion certainly doesn't cite to Price Waterhouse.

Gorsuch:

Burlington:

I find it impossible to believe that a citation to a case that cites Price Waterhouse in that context shows that Gorsuch's "understanding of Title VII was governed by Justice Brennan’s plurality decision in Price Waterhouse v. Hopkins (1989)."

You don't think quoting verbatim from Burlington, hen that quote directly references Price Waterhouse suffices?

That's a pretty anodyne citation; not a controlling one.

Do you think the but of the decision flows from the idea that the term “discriminate against” refers to distinctions or differences

in treatment that injure protected individuals?

A key part of the Gorsuch's logic flows from his interpretation of "discriminate against." Namely, Blackman argues "discriminate against" requires the differential treatment to be motivated by prejudice or biased ideas and attitudes, whereas Gorsuch does not agree that prejudice or bias is necessary.

That debate seems far afield from the proposition he cites Birmingham for.

The discussion pertaining to the term "discriminate against," on page 244 of Price Waterhouse, is itself a quote from an interpretive memo in the Congressional Record. So, it might be more accurate to say Gorsuch's understanding was governed by a memo written by two Senators.

However, I haven't gone back to the original memo, and the direct reference may actually be to a quote within that memo. But I get that a liberal justice is needed as the target of frustration, so the citation trail stops with Brennan.

Maybe an easier explanation is that Chief Justice Roberts bought into the theory behind Critical Legal Studies.

But secretly, without citing to it or following it's reasoning.

Very clever!

When you become a federal government employee you take an oath to support and defend the Constitution. But judges don't mean it when they take that oath. Instead, they ignore the Constitution and support and defend the doctrine of stare decisis. Stare decisis walls the Constitution off from judges, including SCOTUS. Yes, legal continuity is valuable in general, but in many specific cases it is harmful. Every crappy and ill-thought out decision by every crappy activist court somehow becomes written in stone. That "penumbras" picture should really have the Warren court in place of the Earth.

Judges, including lower court judges, should be guided by the Constitution itself. If the Warren Court (or the Roberts Court) made a mistake then it should be treated that way, as an error that should have no bearing on future cases.

Again, because Josh Blackman is not a serious scholar, he throws out red meat (literally, red) without bothering to explain basic concepts.

There is vertical (strong) stare decisis. This is what binds lower courts to the opinions of an upper court. There are incredibly strong reasons why this absolutely has to be followed and respected in our system.

Then there is horizontal (weak) stare decisis. This is what binds a court to its own precedent. Different courts will have different rules for this; for example, a typical rule you might see is that a panel cannot overturn a prior panel precedent, but only the full appellate court (en banc) can.

The Supreme Court has many internal rules about stare decisis with regard to its own opinions; it doesn't usually go into them in exhaustive detail because that would be stupid. The general idea is that:

A. Constitutional Stare Decisis is much weaker than Statutory Stare Decisis. This seems counter-intuitive at first, but it makes a lot of sense once you understand it. Congress can, at ANY TIME, change a statute .... but only SCOTUS can change its interpretation of the Constitution. As such, the Supreme Court is much more unlikely to revisit statutory decisions.

B. The Court is supposed to factor in a number of interests when looking at horizontal Stare Decisis. As articulated by Scalia in his in WRTL, these factors include whether or not the prior decision was "workable" (creating a settled body of law), whether the prior decision involved contract or property rights (or other reliance interests), and whether the decision was rooted in the national culture (call this the Miranda exception).

But there is something profoundly untoward for a law professor (and I use the term loosely) writing a polemic such as this; indicating either a profound and disturbing lack of knowledge, a serious mental illness, or both.

Isn't the democrat sales pitch for Biden :

Vote for Joe, he will appoint Supreme Court justices who will vote to overturn Citizens United??

No, the sales pitch for Joe Biden is pretty simple- you've just seen the absolute worst that can happen. Aren't you tired of it all?

The more that I think about it, the sales pitch for Biden is the same as that for Reagan in 1980.

....but only if Carter was a lying piece of crap.

So you're saying Citizens United is safe??

The same pitch as Harding in 1920.

As far as these "prenumbras" go, I look instead to the ninth amendment. I consider it as something akin to the "general welfare" clause in the original constitution that gives Congress broad discretion and power.

The idea that the only individual rights are those enumerated not only flies directly in the face of the ninth amendment, but it makes no sense to me.

And (back when I regularly commented 'round here) y'all thought I was crazy for saying that social conservatives (which Blackman definitely is among) want to overturn Griswold.

If your idea of "liberty" includes "the government prohibits you from using birth control", you're a fascist. It's really not complicated.