The Volokh Conspiracy

Mostly law professors | Sometimes contrarian | Often libertarian | Always independent

Imagining a World Without Qualified Immunity, Part II

Absent qualified immunity, the rate at which plaintiffs win would remain about the same.

This week, in excerpts from a forthcoming article, I am offering several predictions about a post-qualified immunity world. Today, I explain why plaintiffs' rate of success in civil rights cases would not dramatically change.

This prediction will likely surprise most commentators and courts, who appear to believe that most civil rights cases are dismissed on qualified immunity grounds and that eliminating qualified immunity would dramatically increase the frequency with which civil rights plaintiffs win. But those who hold this view overlook the fact that most civil rights cases that are dismissed fail for reasons other than qualified immunity.

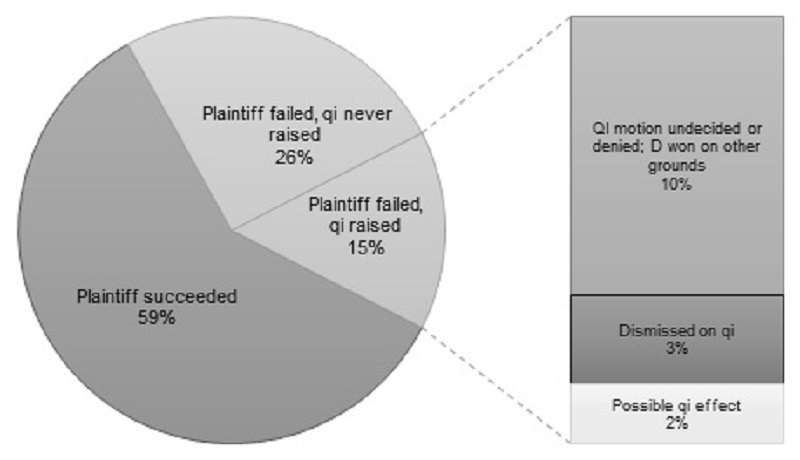

When I studied 1183 civil rights cases filed in five federal districts around the country, I found just thirty-six that were dismissed on qualified immunity grounds. Another 431 cases were dismissed for a variety of other reasons: some were dismissed as frivolous by the court before the defendant ever received the complaint; some were dismissed at the motion to dismiss or summary judgment stages on grounds other than qualified immunity; and some were dismissed following defense verdicts at trial. For every case in my dataset dismissed on qualified immunity grounds, another twelve failed for other reasons. Although there is regional variation in the frequency with which qualified immunity is raised, granted, and dispositive, qualified immunity was not the most common reason for dismissal even in the districts most sympathetic to the defense.

Of course, qualified immunity can cause a plaintiff to fail even if it isn't formally the reason the case is dismissed. The claims a jury would find most sympathetic could be dismissed on qualified immunity grounds, leading to a defense verdict at trial. Or the cost of defending against a qualified immunity motion might use up all of a plaintiff's resources, and cause her to abandon her case.

But there are only a few cases in my dataset in which qualified immunity could have caused plaintiffs to fail in these ways. In 68% of the cases that were dismissed on grounds other than qualified immunity, defendants never raised the qualified immunity defense. In another 22% of the cases, defendants raised qualified immunity as one of several arguments at the motion to dismiss or summary judgment stages, and courts dismissed plaintiffs' claims on other grounds. In 4.4% of the cases, defendants raised qualified immunity at some point during litigation, lost those motions in their entirety, and then prevailed at trial. So, in almost 95% of the cases dismissed on grounds other than qualified immunity, it appears that qualified immunity did not play even an informal role in the plaintiffs' failures.

That leaves us with a total of 60 cases that were dismissed without payment to plaintiff where the result could conceivably be different absent qualified immunity: the 36 cases dismissed on qualified immunity grounds; 11 cases that ended in defense verdicts after qualified immunity motions were granted in whole or part; and 13 cases that were dismissed as a sanction or for failure to prosecute after a qualified immunity motion was filed. Assuming, for the sake of argument, that plaintiffs would have succeeded in all 60 cases in a world without qualified immunity, plaintiffs' success rate would only increase about five percentage points—from 57.7% to 62.8%—across the districts in my study.

But I am skeptical that the dispositions in most of these cases would change.

In all but one of the cases formally dismissed on qualified immunity grounds, courts found that the plaintiffs had not met their burden regarding the constitutional claim or made clear they were skeptical about the cases' underlying merits. Even without qualified immunity, most or all of these cases would have been dismissed because the courts would have found plaintiffs failed to satisfy their burdens of pleading and proof.

Now consider the 11 cases where some claims were dismissed on qualified immunity grounds, and then defendants won at trial. It is impossible to know what the juries in these cases would have decided had they been able to evaluate all the claims and evidence. But plaintiffs in my docket dataset usually lost at trial—regardless of whether qualified immunity was raised. Plaintiffs' attorneys I interviewed and surveyed reported that juries are often more sympathetic to government defendants, and more likely to believe officers at trial. Several attorneys I interviewed predicted that more cases would go to trial in a world without qualified immunity, but that jurors' skepticism about civil rights plaintiffs' claims meant that they would not prevail more often.

Finally, consider the 13 cases dismissed as a sanction or for failure to prosecute. Three were dismissed because counsel failed to comply with court orders after defendants' qualified immunity motions were denied or granted in part on other grounds. In none of these cases is there any indication qualified immunity played a role in their dismissal. Another nine were brought by pro se plaintiffs who failed to respond to motions or comply with court orders—but pro se plaintiffs usually lose, whether or not qualified immunity is raised. For all of these reasons, most plaintiffs in my dataset whose cases were dismissed without payment would not have had better luck in a world without qualified immunity.

So far, I have focused on the cases in which plaintiffs lost. But eliminating qualified immunity could also influence the outcomes of cases in which plaintiffs succeeded. One would assume that most plaintiffs in my dataset who were able to negotiate a settlement or win at trial would be able to succeed in these same ways were qualified immunity eliminated. But eliminating qualified immunity might sometimes cause plaintiffs to decline settlements in favor of trial.

Approximately 17% of qualified immunity motions and 34% of interlocutory and final appeals in my dataset were never decided, presumably because the cases settled while the motions were pending. These settlements may have been motivated by the plaintiffs' uncertainty about how the qualified immunity motions and appeals would be decided. Were qualified immunity abolished, plaintiffs might decide to take more cases to trial. But, as I have explained, defendants win the vast majority of cases that go to trial and attorneys believe jurors are hostile to these cases. So, if cases that would have otherwise settled would go to trial absent qualified immunity, at least some of those plaintiff "successes"—settlements—might turn into failures after trial.

For reasons I will explain on Thursday, eliminating qualified immunity would likely result in more civil rights cases filed. But these additional cases would likely have a similar success rate as cases filed today. Plaintiffs would still have to overcome the same burdens of pleading, discovery, and proof that are today the primary reasons cases get dismissed. And there is no reason to believe that the additional cases filed in a world without qualified immunity would be better able to overcome those obstacles than the pool of cases filed today.

Editor's Note: We invite comments and request that they be civil and on-topic. We do not moderate or assume any responsibility for comments, which are owned by the readers who post them. Comments do not represent the views of Reason.com or Reason Foundation. We reserve the right to delete any comment for any reason at any time. Comments may only be edited within 5 minutes of posting. Report abuses.

Please to post comments

"Or the cost of defending against a qualified immunity motion might use up all of a plaintiff's resources, and cause her to abandon her case."

Maybe a little off topic, but replacing the generic "his" with a generic "her" doesn't actually do anything to solve the problem of English not having ungendered pronouns. It just replaces patriarchy with matriarchy.

Now, if that's your goal, by all means proceed. But if it isn't, maybe something else would be in order?

On the other hand, making a habit of semi-randomly alternating between generic "his" and generic "hers" does solve some aspects of the problem without replacing perceived patriarchy with matriarchy.

It's not a perfect solution but it's less-bad than "its" and worlds better than "xyrs", "hirs" or "zhers".

The only problem with that is that it has the potential to be confusing, because somebody might think the correct gender had actually been designated.

Really, English needs a gender free pronoun.

That, and a second person plural subject pronoun! (The Southern "y'all" works fine, if we make it standard.)

English has a second person plural subject pronoun: "you". The trouble is, we discarded the second person singular pronouns long ago, and use "you" for this that many people don't know it's plural.

And so southerners invented "y'all" - and now they sometimes use that for second person singular, requiring the invention of "all y'all" when they want to make it _clear_ that they mean the plural. If this trend continues, by 2100 "all y'all" will be a second person singular pronoun...

In informal, spoken English, that sentence would often use "them/their," which transforms the plural pronoun to the singular, but is gender neutral (take that, patriarchy/matriarchy). Given that this would otherwise not create any confusion as to the subject at hand due to the use of a singular subject noun earlier in the sentence, and that this is often used informally, I would recommend this as my preferred option. Beats the hell out of "zes," "xyrs," etc.

I think a difficulty with a quantitative approach here is that the overwhelming majority of cases filed are likely completely frivolous. And the completely frivolous cases don’t count from a policy perspective. Everyone agrees they ought to be dismissed regardless of what the standard is.

So the only cases of interest are non-frivolous cases, ones that might win but for qualified immunity.

A purely quantitative approach, or at least one based on all suits filed, can’t distinguish between wheat and chaff here. By treating every lawsuit as equal independently of its merits, it will drown any signal in the sea of noise.

What do you think is the motive for a lawyer to file a case that is “completely frivolous” as you describe it? Is there a reason you think this would be the “overwhelming majority” of cases?

$$$$

Do you believe there is a lot of money in filing cases that are “completely frivolous”?

In my opinion, you are ignorantly buying into hype.

I do think that when people get really angry and have money, there are lawyers willing to tell them they don’t have a case. But there are also lawyers willing to take their money and, when they lose, sympathize with them and tell them it’s a shame that the judge wasn’t being fair.

It’s not often that these cases are considered so frivolous as to result in the plaintiff or the plaintiff’s lawyer being sanctioned. So there isn’t, realistically, much downside or risk to representing a plaintiff in a losing case.

§ 1983 cases, which is when QI generally comes into play, do not involve paying clients. These cases are taken on contingency.

As David notes, there isn't any money to take because the lawyer only gets paid if there's a recovery. The lawyer typically loses money on frivolous cases as a result of filing fees, service costs, and other expenses.

Very few lawyers are filing frivolous cases (in the legal sense) in hopes of making money. A lawyer is much more likely to file a frivolous case in connection with some sort of activism or other social advocacy.

A great many lawsuits are filed pro se.

Potential omitted variable bias in your sampling: any data will overstate the percentage of cases where QI wasn't a factor because of chilling effect from QI.

There is a problem with this analysis, since it does not consider cases which were never brought because they would likely have failed on qi grounds.

Without knowing how many of them there were in the same parameters as the actual dataset, the research has limited value.

That's certainly an issue worth considering, but what do you make of the practitioner's evaluations of cases? It seems they weren't predicting much of a difference, which, if true, would suggest there isn't a lot of chilling.

"Plaintiffs' attorneys I interviewed and surveyed reported that juries are often more sympathetic to government defendants, and more likely to believe officers at trial."

This makes me a sad panda.