The Volokh Conspiracy

Mostly law professors | Sometimes contrarian | Often libertarian | Always independent

The Importance of Making the Moral Case for Immigration

Advocates for immigrants would do well to emphasize moral arguments more than appeals to the narrow self-interest of native-born Americans.

I recently attended a conference on immigration policy. As is often the case, many of those speakers who favor greater openness to immigration argued that advocates for immigrants should emphasize efforts to allay concerns that immigrants threaten the self-interest of native-born Americans. On this theory, more must be done to explain how immigrants can bolster the economy, spur innovation, and contribute to the culture, and conversely why they don't threaten natives' jobs, increase crime, or overburden the welfare state. These issues are all worth addressing. But in focusing primarily on these sorts of questions, I fear many immigration advocates may be overlooking the lessons of past successful efforts to expand liberty and promote equality for groups previously considered unworthy of serious moral consideration.

Relevant historical parallels include the abolition of slavery, the civil rights movement, the women's rights movement, and - most recently - the successful effort to institute same-sex marriage. In each case, success was achieved principally through arguments focused on universal moral principles and on the common humanity the rest of us share with the group in question, not arguments emphasizing how helping the oppressed would promote the narrow self-interest of other parts of the population. Moral appeals were by no means the only factor that mattered in these cases. But their role was central, nonetheless.

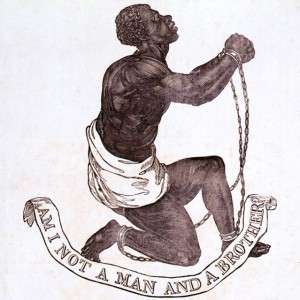

What did more to promote the antislavery cause: the abolitionists' argument that slavery was unjust because black slaves had the same right to liberty as whites, or Hinton Helper's argument that ending slavery would serve the self-interest of southern whites? The answer seems pretty clear. Few if any historians would argue that the latter had more than a fraction of the effect of the former, even though there was considerable truth in Helper's claims. The famous British antislavery image pictured above is another noteworthy example of the key role of moral appeals. It emphasizes that blacks are fundamentally akin to whites, and that there is no justification for denying the former the liberty claimed by the latter. Harriet Beecher Stowe's novel, Uncle Tom's Cabin - the most successful antislavery book in American history - made much the same sort of case. It emphasized the common humanity between blacks and whites and the ways in which slavery was unjust, not the ways in which it damaged the economy or otherwise harmed the interests of whites.

The civil rights movement is a similar case. Martin Luther King's famous argument that segregation should be ended because people should "not be judged by the color of their skin but by the content of their character" was much more effective than economists' (well-grounded) arguments that ending segregation would help jumpstart the southern economy, thereby boosting white incomes.

Much the same story can be told about the women's rights movement, same-sex marriage and other similar examples. Like the civil rights movement, these efforts succeeded largely because a sufficient number people were persuaded that it is wrong to deny people liberty and fundamental human rights on the basis of what are ultimately morally arbitrary characteristics: race, ethnicity, sex, and (most recently) sexual orientation.

Immigration restrictions have important commonalities with past laws restricting freedom based on race, ethnicity, and gender. Like the former, they are largely based on an immutable characteristic stemming from ancestry: in this case, where you were born and whether your parents happen to be US citizens. Both types of laws essentially punish people for choosing the wrong parents.

Like race of birth, place of birth is an immutable characteristic that we cannot change, and one that says nothing about our intrinsic moral worth or how much liberty we should be entitled to. In both cases, discriminatory policies resulted in massive restrictions on the freedom and welfare of the people targeted, all enforced through government coercion. Immigration restrictions, like Jim Crow laws, forcibly confine many of their victims to lifelong poverty and oppression. As economist Alex Tabarrok puts it, "[h]ow can it be moral that through the mere accident of birth some people are imprisoned in countries where their political or geographic institutions prevent them from making a living?"

The parallels between racial discrimination and hostility to immigration were in fact noted by such nineteenth century opponents of slavery as Abraham Lincoln and Frederick Douglass. These similarities suggest that moral appeals similar to those made by the antislavery and civil rights movements can also play a key role in the debate over immigration.

Moral appeals were in fact central to the two issues on which public opinion has been most supportive of immigrants in recent years: DACA and family separation. Overwhelming majorities supporting letting undocumented immigrants who were brought to America as children stay in the US, and oppose the forcible separation of children from their parents at the border. In both cases, public opinion seems driven by considerations of justice and morality, not narrow self-interest (although letting DACA recipients stay would indeed benefit the US economy). Admittedly, these are relatively "easy" cases because both involve harming children for the alleged sins of their parents. But they nonetheless show the potency of moral considerations in the immigration debate. And most other immigration restrictions are only superficially different: instead of punishing children for their parents' illegal border-crossing, they victimize adults and children alike because their parents gave birth to them in the wrong place.

The key role of moral principles in struggles for liberty and equality should not be surprising. Contrary to popular belief, voters' political views on most issues are not determined by narrow self-interest. Public attitudes are instead generally driven by a combination of moral principles and perceived benefits to society as a whole. Immigration is not an exception to that tendency.

This is not to say that voters weigh the interests of all people equally. Throughout history, they have often ignored or downgraded those of groups seen as inferior, or otherwise undeserving of consideration. Slavery and segregation persisted in large part because, as Supreme Court Chief Justice Roger Taney notoriously put it, many whites believed that blacks "had no rights which the white man was bound to respect." Similarly, the subordination of women was not seriously questioned for many centuries, because most people believed that it was a natural part of life, and that men were entitled to rule over the opposite sex. In much the same way, today most people assume that natives are entitled to keep out immigrants either to preserve their culture against supposedly inferior ways or because they analogize a nation to a house or club from which the "owners" can exclude newcomers for almost any reason they want.

Often, such attitudes are not the result of malevolence or stupidity. For many people, they are simply assumed to be part of the natural and inevitable order of things. But of course the same was also true of slavery, racial segregation, and the subordination of women to men. All were also once widely considered an obviously valid part of the natural order, and all were widely supported by generally good and intelligent people. Over time, most westerners came to see that these institutions in fact severely restrict freedom on the basis of morally arbitrary characteristics. As Alex Tabarrok reminds us, "[w]hen in 1787 Thomas Clarkson founded The Society for the Abolition of the Slave Trade… slavery was considered by almost everyone as normal, as it had been considered for thousands of years and across many nations and cultures." Yet, within Clarkson's lifetime, the moral movement he and a few others began led to the abolition of slavery in the British Empire, and eventually helped inspire its abolition in the United States as well.

Effecting a similar transformation in attitudes should be the main long-term goal of immigration advocates. It is not going to be a quick or easy task. But history suggests that it is doable.

History also suggests that it is often easier to get people to expand their moral horizons by building on preexisting intuitions than to consider complex empirical evidence on the effects of government policies on various groups' self-interest. While voters are not, for the most part, selfish, they are "rationally ignorant" about details of government policy. For this reason, among others, it was easier to get whites to see that blacks are fundamentally similar to them than to get them to understand, for example, that letting black workers enter the job market on an equal basis with whites, would ultimately increase white incomes rather than decrease them. The same point applies to moral and empirical arguments about immigration.

None of this indicates that immigration advocates should completely ignore the self-interest of natives. Some issues related to latter are intrinsically important, entirely aside from considerations of political strategy. In addition, people will often ignore or bend moral principles if they believe that is the only way to avoid some horrible disaster. Furthermore a key part of the reason why many fear those of different races or ethnicities is the perception that "we" are enmeshed in a zero-sum game with "them" in which the only way one group can prosper is at the expense of the other. In this crucial sense, moral attitudes cannot be neatly separated from empirical ones. It is easier to expand the scope of the relevant "we" if those added to it are not seen as a dire threat. Even the most effective moral appeals, therefore, are unlikely to end all significant opposition to immigration. But they can go a long way.

They can also make it easier to address fears about the effects of immigration in more humane ways. A person who recognizes that blacks are entitled to the same liberty as whites might still have concerns about large-scale integration. But he or she is likely to be more open to finding ways to address them by means less cruel than barring blacks from white society. If there is a moral presumption against racial discrimination, that means we are obligated to carefully consider other ways of addressing social problems before resorting to it. Similarly, those who accept a moral presumption against migration restrictions based on parentage and place of birth will be more open to considering "keyhole solutions" that address possible negative side-effects of immigration by means less draconian than barring immigrants.

Like slavery, racial segregation, and the subordination of women, immigration restrictions are a complex, multifaceted issue. Advocates for immigrants should not forget that. But they should also keep in mind the crucial role of moral appeals. Like the slave, the migrant fleeing oppression in search of a better life is also "a man and a brother."

Editor's Note: We invite comments and request that they be civil and on-topic. We do not moderate or assume any responsibility for comments, which are owned by the readers who post them. Comments do not represent the views of Reason.com or Reason Foundation. We reserve the right to delete any comment for any reason at any time. Comments may only be edited within 5 minutes of posting. Report abuses.

Please to post comments

Sorry, but we don't need more genetically unintelligent mestizos in America. With their 85 IQs and genetic propensity for violence and disorder, they can only degrade America and bring us down to Latin America's level.

Thanks for helping.

I know nobody likes to think that there are racial differences in IQ, but it's the sad truth.

Then perhaps you'd like to self-deport yourself and raise America's average IQ. Make room for a nice Asian?

I tested at over 150, but thanks for playing.

Then how come your comments here test at 65?

Seriously, your bigotry marks you as an ignorant person.

I sense he is among the authors of the Republican Party platform every few years.

Truth hurt?

Sometimes. Depends on the truth and the person.

Does it hurt to be a contemptible excuse for a human being who spews racism and bloodlust?

I suspect not.

What, specifically, are we discussing? The benefits of immigration vs. a regime of no immigration at all? The wrongfulness of *any* regulation of immigration? Or various competing proposals for immigration laws?

What is the equivalent of enslaving people in this analogy? Imposing any border controls at all?

"What, specifically, are we discussing?"

Exactly. The left screams that the right are racists and Nazis and doesn't want any immigration, the right screams that the left wants open borders and will let everybody in including the TERRORISTS AND CRIMINALS. But nobody ever really says explicitly what they think our policy should be.

I live in Texas, and last night a Beto O'Roarke ad came on the TV. It was a simple commercial that consisted of 30 seconds(?) of him simply talking - mostly beating up Cruz over immigration. But in all that talking, he never really said what he thought an optimal immigration policy should be, other than he likes the "Dreamers" and he thinks our immigration policy should be "a reflection of ourselves", whatever the fuck that means.

Ted Cruz. Hispanic American who is against illegal immigration, and acts "white".

"Beto" O'Roake. White American who takes on a Hispanic nickname.

Why do you place "Beto," but not Ted, in quotation marks?

There is no need to respond if "bigoted rube" is the explanation.

1. Because that's how "Beto" is described in Wikipedia. IE "Robert Francis "Beto" O'Rourke"

P.S.

I wasn't aware that pointing out the cultural appropriation that represents "Beto's" nickname and the crass political nature of it made one a "bigoted rube". Must be nice for "Beto". When he goes to college, suddenly he's "Robert" at Columbia, co-captaining the rowing team.

Then he goes to run in southern Texas against a Hispanic in the primary, and suddenly it's "Beto". Silvestre Reyes, the long standing Congressman loses by just a few hundred votes, in the heavily hispanic district. I suppose having "Beto" as a first name must have been worth a few hundred votes to O'Roarke. Bonus... Democrats get a nice non-Hispanic representing the heavily Hispanic district.

El Paso (and O'Rourke's district, which I live in) isn't in southern Texas.

We're right on the border with Mexico, sure (I literally can see into Mexico from my yard), but that's because Mexico is so much farther north hereabouts than it is to the east.

North-south-wise, we're substantially north of Austin, San Antonio, or Houston, and hundreds of miles north of really "southern Texas" locations like Brownsville.

Fair enough. I switched up the 16th and 23rd districts.

You did not try to explain why the use of Beto should be treated differently from the use of Ted . . . other than your obvious right-wing bigotry.

Carry on, clingers. Continue to show as much character as your hero, Ted 'Call my wife a pig and I'll kiss your ass with a smile' Cruz.

What that tells me is not that either man is doing wrong or is a hypocrite, but that a person can quite legitimately change his nationality if the nation he's changing to will accept him. We make fun of "trans-racial" pretenders, but being "trans-national" can be quite valid. (Which implies nothing about whether the society he wants to move to has an obligation to accept him.)

And yet, the Constitution does spell out in its preamble that the nation of liberty it would perfect and improve is "for ourselves and our posterity," not for the rest of the world (except in the sense that it may inspire by example).

In my view, Cruz is a good example of the kind of immigrant we want to let in -- because he was willing to assimilate. I have strong doubts about whether people who come in in large groups, or belong to a "no peace until we own the world" religion, are going to be willing to do that, and thus preserve the traditions that the US exists to preserve.

And the Equal Protection Clause clearly extends only to citizens. It says so in black and white.

Ilya Somin is on record as saying that even foreign citizens convicted of crimes should not be deported. So it is safe to assume that he considers any border controls as slavery.

Somin has posted before how he is in favor of completely open borders. He's happy to try to conflate open borders with expanded immigration in whichever way will serve his cause, of course.

Slavery was eliminated by killing 300,000 or so Democrats and disenfranchising most of the rest.

Civil Rights by waiting until enough of the re-enfranchisied and their children died.

Same-sex "marriage" was imposed by judicial fiat in one of the most anti-democratic moves by the Supreme Court ever (even if you agree with it, it was definitely anti-democratic.)

Appeals to morality depend upon a having a moral people -- I ain't seeing it.

"Slavery was eliminated by killing 300,000 or so Democrats"

And only as a by-product to saving the Union.

Debatable!

But it's pretty clear that the Union only needed saving because of slavery.

"Debatable!"

Well, I stand with Lincoln in the debate.

Slavery caused the war but without a war, it would have been decades at least until the North got 3/4 of the states to pass a constitutional amendment. Maybe longer.

Remembering that Lincoln was indeed anti-slavery, he was no radical, no.

Considering that parts of the Democrat Party were fighting for white supremacy into the 1960's ... bloodshed was the ONLY way sadly.

Bob trusting a politician. Never thought I'd see the day.

"Bob trusting a politician."

Just certain dead ones.

Actually, if we examine it closely, the Union only needed saving because of moral opposition to slavery.

After all, if there had been no abolitionists, or they had remained politically weak, or the abolitionists who gained power had been Southern whites looking to their own self-interest, there would have been no secession of Southern states in response to an abolitionist party having its presidential candidate elected.

Ah, but, said moral opposition only became viable due to economics!

The establishment of pre-existing rights government may not trod on is indeed anti-democratic. That's the whole point.

I have little problem with "Living Constitutionalism" finding enough people think something is a right, and therefore it is. I would prefer free speech continue to work and government change the law, but that's to stop...

I have much more problem with judges discovering government has the power to control vast new swaths of existence without constitutional amendment.

How to reconcile this apparent discrepancy? Simply recognize the Constitution is really about forestalling dictatorship, and that means securing rights, and stopping growth in power without well-considered amendments granting a power.

I support legal immigration.

Begs the question as to what qualifies as "legal".

Not really. Legal meaning within the framework of the law. As opposed to masses of undocumented people streaming across borders. That being said, immigration laws need serious overhaul, which neither party has been willing take on.

Yes, "really".

Laws don't come out of the ether.

The debate is (or ought to be) more about what the law should be than what the law is.

(If it's about the latter, then the law is much to ambiguous)

I always shut down when I see immigration articles on reason at this point. They are always so extreme. Yes I understand some immigration is beneficial to the country and yes I understand we can try to help those less fortunate by giving them opportunities in the US. I don't think most would disagree.

Just like every other country in the world we cannot allow everyone to come as they please. I don't feel the slightest bit bad about saying so. To me it's common sense but I think I live in the twilight zone now

The fun begins when you consider the federal government to be a pain in the ass that screws everything up, and what would happen if you shrank it to the size of a small room. Don't even need to go that far: eliminate the welfare state and we've got a lot of options.

It's less fun when you go with appeals to emotion that both sides play.

That's fun for uneducated, disaffected, old-timey right-wing bigots -- especially the faux libertarians -- but not a distraction for modern, accomplished, decent, reasoning citizens.

Idiotic post alert

I hereby call for a return to imperialism. Take over little countries. Turn them into states. Crush their local corruption. Bingo. No more need to flee.

It all comes down to self-ownership and individual ownership of property. If the property owner objects, it is trespassing. If the collective government wants to assert ownership of the property without buying it in a fair trade, that is coercion. Collective action like immigration control and tariffs presumes that a majority can dictate private and personal actions like trade, hiring, property rental, and even friendship.

Calling immigrants an invasion is a pathetic misuse of common language and only serves to show how xenophobic they really are.

Complaining they take up welfare and cause crime only shows how ignorant they are, and that they'd rather fight liberty than fight collectivist oppression.

Well, someone is ignorant.

In our school district average per-pupil spending is just north of $U12,000/yr. That doesn't include debt service on capital projects and contributions to the teachers' retirement system.

Low-wage, low skilled immigrants (legal or illegal) don't come close to covering the costs imposed on us by their kids.

And don't forget that they actually consume more, as they are genetically unintelligent and disproportionately require special education and/or ESL

Correct. There are many ways in which illegals get taxpayer support. As just one example, every illegal alien's child is entitled to a public school education (even if the child is also illegal) and the average cost of this education is $11,000 per year (2014 figures). An illegal alien's child enrolled in first grade will cost the taxpayer $132,000 to graduate from high school. This $132,000 of course becomes unavailable to educate the children of citizens and legal immigrants.

So a $25 billion wall will pay for itself if it deters just 190,000 illegal aliens of child-bearing age from crossing the border illegally.

If we can reduce the 500,00 illegal border crossers by 95% to (say) 25,000 per year, then the illegal immigration problem is greatly reduced. At that point, the public will be willing to be more generous with the illegals already in the country, especially if criminal aliens are deported.

Illegal aliens' children ARE citizens.

There are a bunch of other problems with your argument (every single illegal alien of child-bearing age will have a child? That's not how human reproduction works!) but that bit is the most glaring example of your prejudice.

"Illegal aliens' children ARE citizens."

Not true. Depends where the children were born.

Fine pedantry, but correct.

Technically correct is the best kind of correct.

😀

One of my favorite lines in Futurama.

I do think Prof. Somin's moral argument for open borders ignores practicality too much, but the wall is similar thinking - symbolism above pragmatism.

Israel uses a "wall" or fence to keep unwanted visitors out to great success.

We have more ground to cover but we have more resources as well

As a symbol of the governments commitment to fight illegal immigration, it would also give space to resolve other immigration issues.

There is little to nothing about Israel an American should wish to emulate.

It's impractical in terms of resources and even legally in terms of properties. It's utility is going to be less due to it's length. And Israel's situation is very much not our own.

Your symbol argument works just as well reversed in support of Somin's thesis.

Stopping crossing is the very purpose of a wall, and they are very practical. I believe open borders advocates oppose a wall, not because it wouldn't work, but because it would. And because, while other forms of border enforcement can be quietly and inconspicuously discontinued, tearing down a wall would be very conspicuous indeed.

It is not at all clear the wall will stop crossings. Lots of counterexamples of walls not stopping people, including on the border right now.

So the benefit is questionable, and the true cost is not something wall proponents are excited to get into.

It's a talisman, not a project proposal.

What is the "true cost "?

Burden isn't on me; you guys are the ones proposing it and then kinda waiving your hands. At least you've moved away from 'who cares, Mexico will pay for it!'

IIRC The Posts' back of the envelope calculation was $25 Billion, but the lack of risk analysis means it'll cost a lot more than that.

Oh, I thought you were talking about some social or political cost.

In Fiscal Year 2019, the federal budget will be $4.407 trillion. $25 billion spread out over 2 or 3 years is a rounding error. Even $50 billion.

Of course, all of this assumes that these people pay no state or local taxes, including sales taxes. It also assumes that they do not provide income to taxpaying businesses and landlords, nor that these high school graduates will ever contribute to the economy. If you are going to do a cost-benefit analysis, you should consider more than just cost.

Given that most of them are low IQ mestizos, that they won't be economically productive is a fairly safe assumption.

I suppose this sort of wild, fact-free generalization makes some sense to a white supremacist.

It has become bread and butter to Republicans. Have you watched Fox News lately?

Are you seriously disputing that American Indians have a much lower average IQ than whites and East Asians? Most "Hispanics" are mostly Aztecs and Mayans.

So are you implying that illegal immigration doesn't cost the taxpayers?

Yes, I am suggesting that this is a distinct possibility. Another benefit taxpayers receive is state and federal withholding tax. To draw wages, many illegals use fake social security numbers. Taxes are withheld, but do all of the workers claim the refunds? They also pay wage taxes--social security, etc. How many collect on social security and Medicare? Added to the local taxes they pay and the income they provide to landlords and businesses, there may be a net benefit.

Immigrants who pay rent indirectly pay property taxes. They pay sales taxes.

"indirectly pay property taxes. They pay sales taxes."

The property taxes could be indirectly paid by other tenants. The property owner pays directly in any event.

Most of their purchases [food and clothing] is often exempt from sales tax.

They also mainly fail to pay income taxes.

If one kid is at school, they consume more tax dollars than their measly sales tax payments. Only goes up with multiples

In my state the top for expenses for illegal aliens: rent, clothes, food and remittances are all sales tax exempt, so they are paying a few hundred dollars at most. The portion of the rent on 2-bed room apartment that would go to property tax is less than $2000/yr. Meanwhile 2 kids in school is $25,000yr. and that's just school. Let's get into free lunches and EMTLA. Oh and another U$30,000 or so when mom has another kid that Medicaid will pay for.

How would you describe a mob of 7,000 (and growing) heading North?

Neat use of mob.

Do you have a term you'd prefer to use?

Group. Or just 7,000 depending on the semantic context.

They are not violent, nor have I seen much evidence that they are disorganized.

"Just a random group of 7000 people who have already stormed over attempts to stop them at other countries and declined amnesty in Mexico".

Yup.

Totally not a mob.

'stormed?' Where is that quote even from?

Supporting one questionable word choice with another doesn't actually make your argument more convincing.

"How would you describe a mob of 7,000"

A mostly male column flying a foreign flag is more of an infantry regiment than a mob.

They're missing arms and a mission to kill, which infantry (and invaders) have.

Your overheated rhetoric is just getting silly now.

I believe John Bouvier's constitutional law dictionary has entries for both 'Invasion' and 'Public enemy'. Ironically, the word mob is specifically used.

You claim it is trespassing, but by your own logic, the collective government shouldnt have any power over me being on your property. That is a collective action as well.

Considering the following entry from John Bouvier's constitutional law dictionary, I suspect you are correct about the term 'invasion'.

INVASION. The entry of a country by a public enemy, making war.

What about the moral case for ALL of the people in these impoverished areas? The only real hope is for those lands to be healed and their own countries to improve.

Siphoning off their good people is liable to only make matters worse. It will also greatly encourage and accelerate overpopulation, if you believe that's a valid concern.

Besides the 'commerce' aspect of migration, and besides defending against the potential for 'invasion' (whatever the original understanding of that word is), and besides those who choose to pursue naturalization, isn't authority over which non-citizens occupy state reserved to the states?

Actually, considering the current 'Honduran caravan', I'm increasingly interested in discovering the original constitutional meaning of 'invasion' as understood be the generation that ratified the text.

I see I left out the word 'territory' when intending to say "isn't authority over which non-citizens occupy state territory reserved to the states?"

According to Gallup, 147 million people -- or 4% of the world's adult population -- would move to the U.S. if they could. This includes 37 million from Latin America, who face no ocean barriers. I think that Ilya is arguing that they should all be allowed to immigrate. Those whose talents cannot generate at least the minimum wage worth of value will necessarily go onto the welfare rolls. It would probably be less expensive, and preferred by many of these people, if we encouraged them to stay where they are and just send the checks to them there. Money will go a lot further in Honduras and Liberia than it will in Los Angeles.

I doubt Prof. Somin is arguing for that.

I doubt Prof. Somin is arguing for that.

I think you're wrong about that. Prof. Somin appears to be arguing for open borders. He describes his limiting principle this way:

He claims that history teaches that immigrants do not increase the welfare rolls, but really, can all 147 million have the skills necessary to generate the minimum wage worth of value? Why not limit the open border policy to the highly skilled? Then the low-skilled people already here won't have their lives made more difficult.

If you follow his many posts on the topic, you'll see that he has never argued for any restrictions on immigration. He is an open borders extremist.

When I saw the gist of this article, I knew it was Somin.

IIRC, the Gallup poll which I saw recently found that 14% of the world's population would prefer to live in the US, Western Europe, Canada, or Australia. That's about a billion people. I was skeptical of the poll because (1) I couldn't conceive of how Gallup could conduct an accurate poll of the entire population of the planet; and (2) the number...14% or one billion....is almost certainly far too low. The number of people who rationally would rather live in your neighborhood, or mine, in the US than where they live right now, would be in the billions. North Korea. Venezuela. Sub-saharan Africa. Bangla Desh. The barrios of Brazil. Syria. Rural China, rural India. Mauritania. Even Russia....ask Prof. Somin. When you advocate open borders this is the reality that you are advocating....the mass immigration of entire populations from dysfunctional societies to (relatively) functional societies, inevitably destroying the latter. And then there were none.

Intolerance-based arguments and fears were aimed by substandard Americans at Italians, Asians, Catholics, women, eastern Europeans, agnostics, Hispanics, gays, atheists, the Irish, blacks, women, and others. Any reason to expect the current batch of bigots to be more successful or admired in modern America?

But carry on, clingers. So far as your betters permit, anyway.

I agree with the comment about no one wants to say what the policy should be.

I believe our policy should be relatively open but not unlimited. What the limit should be ought to be set on the ability of our economy to absorb new people of all skill levels. I also think we should know who is in the country. That starts with controlling the border and knowing who crosses it.

The present "system" advantages nearby low skill immigrants who can cross the border surreptitiously over similar immigrants from more distant. Remember that crossing the boarder surreptitiously is not without cost. Many pay "coyotes" significant sums of money to avoid the Border Patrol.

It is not hard to imagine if we had truly open borders and accepted all comers that there would be arise a trade in immigration served by large aircraft flying thousands of people a day into airports around the country, similar to the transatlantic steamship trade of the late 19th and early 20th century where ships like Titanic were build primarily to transport large numbers of immigrants to the US.

We have a mob of 7,000 or so coming here.

Should we let them in?

Why should we? You cannot claim asylum as they are crossing through Mexico who is actually the one legally obligated to offer asylum.

Like slavery, racial segregation, and the subordination of women, immigration restrictions are a complex, multifaceted issue.

I agree that immigration restrictions are a "complex, multifaceted issue." The other three, not so much.

Successful immigration from the viewpoint of the native culture requires 2 rules.

1. The immigrating population must assimilate into the native population.

Quite simply, if the immigrating population doesn't assimilate, you have at best, two conflicting cultures in the same space. At worst, the immigrating culture overtakes and eliminates the native culture.

2. There needs to be time, space, and a low enough proportion of the immigrating culture in order to assimilate readily. Put 1 immigrant in a town of 100, and assimilation is fast. Put 20 immigrants in a town of 100, and assimilation is much slower. Put 100 immigrants in a town of 100, and assimilation doesn't occur.

What does this mean from the context of the United States, one of the greatest nations in history in its ability to assimilate multiple cultures into a large melting pot? Simply speaking, the foreign born population is quite high (over 13%, a 50 year high), and is reaching that point where rates of assimilation drop dramatically due to too great a proportion of the culture to be assimilated. Moreover, additional factors slow that rate of assimilation (a high degree of communication with the home country, which wasn't present in the early days of the country. Also, a high proportion of illegal immigrants, which limits assimilation). A "cooling off" period is needed in order to assimilate the current foreign born population, which necessitates actual enforcement of our current immigration laws.

The moral case for immigration has already been made perfectly well, and we live by it. For the vast majority of us it's ILLEGAL immigration that's the problem. That's ILLEGAL. What is it about this word that a lawyer can't understand? The writer does not favor immigration - he favors open borders, just like Hillary and her ilk do. They know they can't say it without losing millions of Americans, so they try the bait and switch and hope we don't notice.

I looked up the word 'disingenuous' once. It said 'a euphemism for dishonest.'

The people arguing against Muslim and Hispanic immigrants are the successors to intolerant, ignorant Americans who hated and discriminated against Italians, Asians, gays, Jews, blacks, the Irish, Catholics, Hispanics, women, agnostics, eastern Europeans, atheists, and others for reasons related to immigration, skin color, religion, and perceived economic pressure.

America has survived -- more accurate, been strengthened by -- the cultural invasions of linguine, egg rolls, bagels, collard greens, Jameson, the Friday fish fry, tacos, hummus, pierogis, German potato salad, lutefisk, and sushi. I am confident we can handle another wave of immigration and overcome another episode of anti-immigrant backwardness.

This latest batch of bigots seems nothing special.

The difference is that Europeans didn't have average IQs of 85.

l credit the Man Of Many Names for being the sole conservative willing to engage on this point.

Carry on, clingers. While you still can.

Do you deny that intelligence is not evenly distributed among the races?

Your arguing with an NPC. FYI

LOL this is the dumbest meme.

Few people will argue against the morality of immigration and helping those who need help. But, that is not the case at hand.

Having mass crowds of people (funded by a Communist party of Cuba, Venezuela and Honduras) swarm the border in total defiance of laws is not moral. It's illegal and it's aggression.

Either we are a country of laws, or we are not a sovereign country.

These caravans have been a thing for a long time, Trump just likes to whip up the masses. This isn't some leftist plot.

If you're taking the President of Honduras' word for the leftist nature of this caravan, he said that in a conversation with Pence about continued foreign aid to his country...I'd like a bit more proof.

Your final line is cute, but asylum is what this group is seeking, and that is a law.

Moreover, we don't enforce out internal laws to their fullest extent - in fact, that's a cannon of legal interpretation.

Asylum IS a law, and that law is that it must be sought in the first country the refugee goes to, not the one they like the best. So at a bare minimum Mexico should be the one legally obliged to offer asylum. Why are we the only ones expected to follow these rules?

IS that in the US law? I'm no expert, but that's news to me.

And I'm pretty sure we can't bind Mexico with our laws.

These folks can seek asylum if they make it to the border, but only about 3k to 4k TOTAL from Latin America are granted refugee status every year (and it might be lower now under Trump) so the odds are that most of the asylum applications will fail.

I don't know how many intend to apply for asylum as opposed to intending to cross as undocumented immigrants.

It doesn't surprise me Sarcastro that you think laws are cute: you always play the role of parrot to the Liberals talking points of the day quite well. regardless of the lack of logic.

News agencies are reporting that the purpose of the caravan, that was created by militant leaders of the Libre Party, is to cause a crisis and chaos in the region; if you followed foreign policy you'd be aware that former president Zalaya is on a collision course with the current president of Honduras in an attempt to bring down the government so he can take back control.

The thinking goes that Zalaya alaong with other military dictators are intentionally duplicating the crisis that led to the Mariel Boat Lift of 1980, or the recent wave of one million immigrants from the ME to Europe in one year

I have a liberal PoV, but it says more about the narrative you seek about your opposition than me that you think I'm a parrot.

News agencies are reporting is great passive voice, but as I said, given that this is hardly the first such caravan, I'll need more than blandishments.

The thinking goes, eh? Do you realize that admits it's all speculation. A story too convenient to check, I guess.

I did some Googling as well. Snopes has a pretty good writeup. It even has citations!

Yea, the thinking of the foreign policy experts analyzing this situation wasted years of their time, money and effort to understand their areas of expertise. It was totally useless. Evidently they merely needed to call you.

In another time of 60 years ago, 10,000 people massed at the border aiming to crash through would have been referred to as illegal and as an invasion by many. But now, as the Democratic Party is losing power, they need votes and the Republican Party needs a wedge issue, so citizens have to sit back, memorize and vocalize the party line of their choice and watch 10,000 people crash the gates of our country.

Pass the popcorn.

If you are going to appeal to the authority of 'foreign policy experts' you will need to cite them. Not even mentioning their names is a tell.

They are not aiming to crash through, they are seeking asylum.

And illegal aliens can't vote. And they are incentivized not to, as they want to stay under the radar.

They're not eligible for asylum, and you know it.

You sure seem up on asylum law, Mr 'their blood is too impure.'

They are not being persecuted. They're economic migrants. Period.

Question begging, but no death threats.

Well done.

Lemee see. The moral argument does like this. America is so wicked and sinful that unlimited low skill immigration that drives down the wages of low skill low income native Americans is a price we have to pay for our collective sins.

Horse feathers. If these immigrants were driving down the earnings of lawyers and the professoriate rather than laborers, betcha a nickel this blog would be demanding a wall. The well to do reap the benefits of low skill low wage immigration, please don't tell us how moral that is.

Way to not read the OP.

The problem is not "legal" versus "illegal." That's a smokescreen. The problem is that we're importing a racial problem.

NPC

What is an authoritarian right-wing bigot doing at a libertarian site, Tempe Jeff?

The Alt Right's latest is the idea that all liberals are soulless stimulus-response creatures, and that only they are enlightened fully sentient Non Player Characters.

How they managed to make objectivism even more partisan and sad is beyond me.

Also, a key difference from the past is that European immigrants were largely too proud to take welfare. Third-world immigrants from Latin America and Africa have no pride whatsoever. They're more than happy to mooch off the taxpayers and produce illegitimate crotch droppings they can't afford.

I support the present legal immigration levels and would like to see the present family-based rules continued. I absolutely and vehemently distrust all studies which claim to prove that illegal immigrants have a lower crime impact on our nation than people born here. These statistics are achieved by an extremely dishonest grooming of the data of who is passing through our jails and prisons. Most criminals are not sent to trial and convicted (or plea bargained) to become a statistic, they are deported to save jail space. Thus they don't even get counted as a crime statistic. Also the illegal criminal toll is then compared to inner city blighted area crime levels, which is another intellectual dishonesty.

What is really happening is that there is a tremendous proportion of illegal aliens involved in arrests, but the prosecutions are not followed through on because witnesses disappear or the charged people bail out and then vanish. All that activity is not being accounted for, and neither is all the drug distribution infrastructure in America that is right in our face.

Also consider that DWI, auto theft, check fraud, identity theft, shop lifting, and domestic violence and chronic bad driving in unsafe, uninsured vehicles also pose a real threat to the actual health and safety of most of us. You get smacked by an illegal in an uninsured, untitled car who disappears you'll find out.

The family-based rules are absurd. Just because we give a diversity visa to an 85 IQ mestizo doesn't mean we should let in 20 of his siblings, cousins, and other equally useless welfare cases.

We should revisit founding-era prohibitions on ownership of real property by aliens.

We should build the wall.

Until the wall is built, we should defend our borders with the ferocity of a proud nation under attack.

Should the federal government refuse, Texas can and should defend its own borders from this hostile assault.

Nothing has done more to diminish the quality of life for the United States middle class through higher housing (land) costs, greater competition for jobs, lower wages, higher taxes to pay for greater poverty, mortgage fraud, medicare fraud, tax fraud, other crime, higher taxes to pay for indigent healthcare (hospital closings), higher taxes for cost of public schools, price of college, degradation of the military, depletion of resources, burden on the taxpayer and overall congestion than the INCREASE of and change in the nature (more poor, more criminals, e pluribus multum) of the POPULATION since 1965, driven almost entirely by late 20th century entry of migrants (immigrants, illegals, h1b visa holders, visa overstays, refugees, etc) their families and descendants.

"There were these forces operating to strangle economic freedom, which the average American vaguely felt and loudly cried out against . . .

Many of these forces proceeded . . . out of causes no more malignly devised than the mere fact that the average man had increased greatly in the number of him residing upon the American continent.

The average man was being circumscribed in his freedom by the mere increase in his numbers."

Mark Hanna in Our Times, Vol 1, Chapter 9 - on the mood of the country in 1900

In a libertopia governed by a robot who could never be deposed this argument would hold. But in the world of men even dictators are subject to the whims of the governed (aka Bread and Circuses).

Thus, the moral case for immigration must include a discussion of how it will increase freedom in aggregate, taking into account the political preferences of moving populations. Since the Professor continually refuses to engage with this point, his discussions are not interesting in the least.

Exactly.

Ridiculous to equate "immigration restrictions" with racial segregation and slavery.

Our governments have a moral, constitutional, and legal obligation to its citizens, not to immigrants. Such a careless, feckless treatment of our beautiful system of government.

One could easily argue that each wave of immigration changes substantially the future of our Constitution and system of government. (1) Influx during the civil war: rape of Southern women--black and white alike--pillaging of southern towns, and radical changes to the federal structure of our Union. (2) Wave of immigrants 1890-1920: income tax and direct election of senators--radically altering the relationship between the People and the federal government, for the worse, and directly contributed to the depression. (3) Chain Migration Wave, 1980-Present: TBD, but most new arrivals are prepared to eradicate the first and second amendments. More immigrants? No Thx.

He wan't equating immigration restrictions to racial segregation and slavery. He was making the point that moral arguments against racial segregation and slavery were more effective than economic ones, and that the same may be true for arguments against increasing restrictions on immigration. Even if you disagree with the idea that there IS a moral argument for immigration and/or open borders, there is no doubt that he is right about the efficacy of moral arguments as opposed to economic ones.

My difficulty here is that I agree with Professor Somin that Americans can and sometimes ought to, on moral grounds, provide at least limited benefits and protections for those who are outside society and who have no de jure claim to rights against it.

The difficulty here is the line of cases, most notably Roe v. Wade but others as well, which not only pitted the Constitution squarely on the side of scrutinizing morals legislation for potential violation of Americans' interests, but has tended to suggest, in cases such as Lawrence v. Texas, that morality itself is an inherently irrational business which is a suspect and often unconstitutional basis for government policy.

My personal view is and has always been that the constitution leaves such matters to legislatures, neither mandating nor prohibiting morality as a consideration in legislation and policy. My view has also been that legislatures are entitled to compromise, tempering moral considerations with considerations of interest, in a manner which might make no sense or might appear irrational to a purist on either side.

But this is simply not the way the courts have ruled. The courts have ruled that the interests of those inside the constitutional umbrella trump moral considerations about those outside it.

While the Roe permits states to outlaw late term abortion, it doesn't require it. Several states permit it. Many supporters of abortion continue to object to the restricting it.

The bottom line here is that the constitution doesn't really distinguish the status of an extraterritorial alien from that of a late-term fetus. There are, for example, no restrictions on the war power. We can make it lawful to kill foreigners for any reason or no reason. Just as nothing in the constitution prevents late-term abortion for any reason or no reason, nothing in the constitution prevents Congress from passing a law declaring it open season to hunt foreigners for sport if it wants. It would doubtless have to break treaties to do so, but it has the power to do this. And not just extraterritorial foreigners. The Supreme Court has repeatedly said, in upholding the portions of the original Alien and Sedition acts applicable to foreigners, that at common law war made citizens of the enemy country outlaws, removing all legal protections and making it lawful for Americans to plunder and kill them on sight. So putting them in concentration camps instead, far from being unconstitutional, represents a constitutionally unnecessary act of mercy and grace.

(Cont.)

If President Trump doesn't like Mexicans, the stark reality is Congress could declare war on Mexico, break some treaties, replace some laws, and we could simply rob, kill, and quite likely rape them off, and nothing in the Constitution would prevent it. The brutal reality is the constitution no more requires distinguishing unwanted civilian immigrants from a military invasion than it requires distinguishing unwanted late-term fetuses from a disease.

That's the brutal reality. My difficulty with Roe isn't its declaration that the constitution doesn't protect fetuses. It doesn't protect foreigners either. This is why, as Justice Rehnquist noted in his dissent, there was nothing illegitimate about this aspect of Roe. My difficulty with Roe is that it cast grave constitutional doubt on the legitimacy of, and pitted the Court against, the very concepts of morality Professor Somin now seeks to appeal to, concepts that have traditionally prevented what the Constitution permits from being pushed to its limits.

In the first Carhart case, Justices Stevens and Ginsberg's concurrence declared moral sentiments against torture irrational and unconstitutional, and declared that the constitution protects professionals from being hampered by moralists. The view that traditional moral sentiments are irrational or represent an establishment of religion hasn't won a majority. But since Roe, it's always represented a significant minority of the Court's Justices.

(Cont.)

As C.S. Lewis put it, "They castrate, and bid the geldings be fruitful." You can't spend decades undermining the legitimacy of the very concept of morality as a basis for government policy, and then expect to be able to appeal to it when it's your tower that's toppling. That's the bottom line.

In the chapter on "The Lillelid Family Massacre" in The Scarred Heart by Helen Smith (Callisto, 2000, ISBN:0-615-11223-4), there is this passage:

"After the murder, the six teens took the Lillelids' van and headed for Mexico, hoping to go there and start over, maybe raise children. Their dreams came to an abrupt end when they hit the Mexican Border. They were stopped and turned back because they did not have a permit to get into Mexico. In order to obtain a permit, they would have had to produce money or a credit card or risk being turned away. Mexican Customs is very strict and would not let them in; they were sent back through U.S. Customs."

June 1997. The Pikeville Kentucky Six (aged 14 to 21) had murdered the Lillelid family from Knoxville Tennessee to commandeer the Lillelids' van as more roadworthy than their Chevy Citation. They had attempted to migrate to Mexico. The Mexican authorities were unaware of the crimes by the Six; they did enforce Mexican standards for allowing entry by foreigners. They were turned away by Mexican Customs protecting the Mexican border and Mexican sovereignty.

Why should the border and sovereignty of the U.S.A. deserve less respect than the border and sovereignty of E.U.M.?

Besides that, if U.S.A. is the hellhole described by Michael Moore and others, would it not be an act of mercy to prevent not only illegal migration into the U.S.A. but also save those benighted souls seeking legal immigration?

What about the moral imperative to limit human population before we destroy the planet? Why should we not restrict the overflow of yet MORE breeders into the US?

That'd be all fine if group performance differences weren't blamed on white racism. If no one was advocating redistribution and other evil policies based on these differences, i wouldn't care.