The Volokh Conspiracy

Mostly law professors | Sometimes contrarian | Often libertarian | Always independent

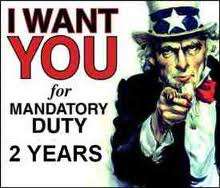

Why Mandatory National Service is Both Unjust and Unconstitutional

A post based on my presentation at a panel on mandatory national service organized by the National Commission on Military, National, and Public Service.

Earlier this week, I spoke at a panel on mandatory national service organized by the National Commission on Military, National, and Public Service. The panel consisted of several legal scholars with divergent viewpoints on the issue, which we understood as focusing on mandatory civilian service, not just the military kind. The following post is a revised version of my presentation to the Commission. I was told that the Commission does not currently plan to publicize an audio or transcript of the panel. If that changes, I will post a link. In the meantime, I am happy to make my own presentation public here. It explains why the enactment of mandatory national service would be both unjust and unconstitutional:

I. Why Mandatory National Service Is Unjust.

Mandatory national service is not just another policy proposal. It is an idea that undermines one of the fundamental principles of a free society: that people own themselves and their labor. We are not the property of the government, of a majority of the population, or of some employer. Mandatory national service is a frontal attack on that principle, because it is a form of forced labor - literally so. Millions of people would be forced to do jobs required by the government on pain of criminal punishment if they disobey. Under most proposals, they would have to perform this forced labor for months or even years on end.

We rightly abhor the extensive use of forced labor by authoritarian regimes, such as those of the Nazis and the communists. The same principle applies to democratic governments. The fact that a violation of fundamental human rights may have the support of a majority of the population does not make it just. Wrong does not become right merely because a large number of people support it.

It does not matter if the work the forced laborers are required to do has great value to society. The same was true of much work performed by slaves and forced laborers throughout history. The cotton grown by slaves in the antebellum South, for example, was considered vital to the American economy. That fact did not make slavery just, nor relieve plantation owners of the obligation to use only voluntary labor.

We can imagine hypothetical circumstances where forced labor is the only way to forestall an even worse outcome, for example if a military draft is the only way to raise an army large enough to prevent conquest by a brutal totalitarian regime. But no such painful dilemma threatens the United States today. The federal government has plenty of ways to recruit needed labor by voluntary means. If it needs more workers for some type of job, it can increase wages and benefits, provide tax incentives of various kinds, or hire more outside contractors. If these methods fail, there are millions of people outside the US who would be happy to do work needed by the government if they have the right to live in the US. There are many good reasons to liberalize immigration policy. If the federal government is suffering from labor shortages, this one could be added to the list.

What is true for civilian labor is also true of the military. With a population of over 300 million, the US could greatly expand its armed forces without resorting to a draft. Indeed, especially under modern conditions, a volunteer armed forces is likely to perform far better than one composed of conscripts, which may be one of the reasons why recent veterans oppose the reintroduction of the draft at even higher rates than the general public.

Some advocates of mandatory national service claim that it can help us achieve a greater sense of national unity by exposing draftees to people from other backgrounds. Perhaps so. But we could achieve even greater national unity by suppressing dissenting speech and religion. Yet we rightly recognize that unity is not a valid justification for violating these fundamental human rights. The same goes for the right to be free of forced labor. A unity achieved through coercion is not worth the price. Such unity could even be actively pernicious, since it could be used to promote further restrictions on liberty in the name of national solidarity. The better path to curbing civil conflict is not to increase the amount of coercion imposed by the federal government, but to reduce it, thereby diminishing our reasons to fear those with opposing political views.

Former Democratic Rep. Charles Rangel, and others, argue that we need a military draft to ensure that the burden of military service is distributed more equitably and to prevent the public from being too ready to go to war. I criticized such claims here. Among other things, the evidence simply does not support the notion that people who are likely to see combat are thereby more opposed to military action than those who are not. The exact opposite may well be closer to the truth.

The above analysis assumes that a mandatory national service program would be enacted and administered by a well-intentioned and competent government. Any actual national service program, however, would be controlled by real-world politicians and bureaucrats. If you are a liberal Democrat, do you really believe that Donald Trump and his ilk can be trusted with wide-ranging authority to impose forced labor on the public? If you are a conservative Republican, would you entrust such authority the likes of Hillary Clinton or Elizabeth Warren? The truth is that none of these people are worthy of such vast power, and the same goes for most, if not all, of the rest of the political class.

II. Why Mandatory National Service is Unconstitutional.

The constitutional issues raised by mandatory national service are not as important as the moral ones. Nonetheless, any such proposal is likely to be unconstitutional, as well: if it includes civilian service, it would be beyond the scope of federal power, and it also violates the Thirteenth Amendment.

One of the bedrock principles of American constitutional law is that the federal government only has those powers granted by the Constitution. Other authority is reserved to the states, or the people. A military draft is likely authorized by Congress' Article I power to "raise and support armies." But there is no such provision authorizing the imposition of mandatory civilian national service. It is possible that Congress' power to regulate interstate commerce can be stretched to justify mandatory national service. Under badly misguided modern precedents such as Gonzales v. Raich, the Supreme Court has ruled that the commerce power allows Congress to restrict any "economic" activity that has a substantial impact on interstate commerce. Failure to perform labor mandated by the government would likely affect interstate commerce, and so could in theory fall within the scope of the Commerce Clause.

But even the most expansive judicial decisions interpreting the commerce power still apply only to situations where Congress is regulating some sort of preexisting economic activity. In NFIB v. Sebelius (2012), the Obamacare case, the Court ruled that the commerce power does not allow the federal government to force people to engage in new economic transactions that they would prefer to avoid: in that case, by forcing them to purchase health insurance. As Chief Justice John Roberts put it, the commerce power is the authority to regulate "preexisting economic activity." He explained that "Construing the Commerce Clause to permit Congress to regulate individuals precisely because they are doing nothing would open a new and potentially vast domain to congressional authority." What is true of purchase mandates is even more true of the power to impose forced labor. Indeed, allowing the latter would be a far greater expansion of congressional authority than the former.

The same goes for efforts to justify mandatory national service through some combination of the Commerce Clause and the Necessary and Proper Clause, which gives Congress the authority to enact legislation "necessary and proper" to the execution of other powers given to the federal government. Even if forced labor might be "necessary" in the Supreme Court's expansive sense of the term, it is not "proper." The requirement of "propriety" is a distinct, separate limitation on federal power. As Chief Justice Roberts explained in NFIB (following a famous formulation presented by Chief Justice John Marshall in 1819), even a "necessary" power can only be proper if it is merely "incidental" to one of the other enumerated powers. It cannot be a "great substantive and independent power." A general power to impose forced labor any time doing so might affect interstate commerce is pretty obviously a "great… and independent power," if anything is.

The Court in NFIB ultimately upheld the individual mandate by reinterpreting it as a tax (wrongly in my view). But it is unlikely that any mandatory national service program worthy of the name could meet the Court's fairly restrictive criteria for qualifying as a tax. Among other things, failure to serve could only be punished with a relatively small fine, and resisters could not be classified as lawbreakers or subjected to criminal sanctions.

In addition to exceeding the scope of federal power, a mandatory national service program would also violate the Thirteenth Amendment, which bans not only slavery, but also "involuntary servitude." The point of the latter restriction is to forbid forms of forced labor that do not go as far as slavery. Here, I have to admit that Supreme Court precedent is against me. In Butler v. Perry (1916), the Supreme Court upheld a Florida law that required citizens to perform forced labor on the state's roads or pay a $3 tax. But, for reasons outlined here, I believe Butler was a badly flawed ruling, and a similar case might well not be decided the same way today:

The option of paying a small tax prevents this program from being a true forced labor provision. According to the CPI inflation calculator, $3 in 1916 is equivalent to $57.69 in 2006 dollars, not exactly a backbreaking imposition. After all, there would have been no Thirteenth Amendment issue had Florida simply required all male citizens to pay an annual $3 tax for road upkeep without giving them the option of performing labor instead…

However, Justice McReynolds' opinion for the Court doesn't rest on any such narrow ground. Instead, it strongly suggests that the law would have been constitutional even if the options of paying $3 or hiring a substitute were not available. According to McReynolds, "the term 'involuntary servitude' was intended to cover those forms of compulsory labor akin to African slavery which, in practical operation, would tend to produce like undesirable results. It introduced no novel doctrine with respect of services always treated as exceptional, and certainly was not intended to interdict enforcement of those duties which individuals owe to the state."

There are several problems with this formulation. First and most important, if the term "involuntary servitude" really does not apply to traditional "duties" to the state, there would have been no need for the Amendment's exception for the use of forced labor as punishment for a crime. As I explained more fully in this post, using forced labor to punish criminals was a longstanding tradition, and was surely not considered "akin to African slavery." Second, McReynolds' argument elides the hard question of determining what evils really were "akin to African slavery" and likely to "produce like undesirable results." The "free labor" ideology underpinning the Thirteenth Amendment was based on a broad opposition to all forms of forced labor as inimical to a free society, not merely those based on racial categories or those that involved lifelong slavery…. Finally, McReynolds' argument seems to elevate the supposed subjective intentions of the framers over the plain text of the Amendment, which is clearly not limited merely to those forms of "involuntary servitude" that are "akin to African slavery" but instead bans all such servitude with the sole exception of forced labor used to punish convicted criminals…

[I]t is worth pointing out that McReynolds' opinion ignored (probably deliberately) the likely racial context of the Florida law. In 1913 Florida (the year when the law was enacted), it is highly likely that such a statute would be enforced primarily against poor blacks, and might even have been enacted for the specific purpose of conscripting black labor under the guise of a facially neutral law.

In sum, Butler is a badly flawed precedent that I hope the Court will overrule when and if an appropriate opportunity arises. More controversially, I also oppose the Court's 1918 ruling upholding constitutionality of the military draft against a Thirteenth Amendment challenge. That one is far less likely to ever be overruled. But we should at least avoid extending it to cover other forms of forced labor.

Defenders of mandatory national service sometimes cite mandatory jury service as a relevant precedent. I think that case is distinguishable on legal grounds for reasons summarized here, and on moral grounds because it usually lasts for only a short period of time and (at least in most states) is relatively easy to avoid. That said, I do in fact oppose mandatory jury service on both moral and pragmatic grounds. Among the latter is the fact that it is often cited as a precedent justifying imposition of more severe forms of forced labor.

In sum, mandatory national service would be unconstitutional, at least if it applies to civilian service, as well as military. Far more importantly, it is deeply unjust.

UPDATE: I have made a few minor additions to this post.

Editor's Note: We invite comments and request that they be civil and on-topic. We do not moderate or assume any responsibility for comments, which are owned by the readers who post them. Comments do not represent the views of Reason.com or Reason Foundation. We reserve the right to delete any comment for any reason at any time. Comments may only be edited within 5 minutes of posting. Report abuses.

Please to post comments

So a draft violates the 13th Amendment, but forcing a baker to make two men a "wedding" cake is all fine and dandy?

Yes, in the context of 13A. You can't differentiate between them merely because you're not very smart. Masterpiece implicates 1A and I hope the baker is ultimately allowed to refuse on religious grounds, but it's not an involuntary labor problem.

there is labor involved... he is doing it involuntary...

How is the labor not involuntary here?

"The National Commission on Military, National, and Public Service was created by Congress to consider and develop recommendations concerning the need for a military draft, and means by which to foster a greater attitude and ethos of service among American youth. Established on September 19, 2017, the Commission intends to issue its final report no later than March 2020 and conclude its work by September 2020.

"Evidenced by Statute and Principles issued by the President, the Commission's mission is to listen to the public and learn from those who serve to recommend ideas to foster a greater ethos of military, national, and public service to strengthen American democracy. The Commission hopes to ignite a national conversation around service and, ultimately, develop recommendations that will encourage every American to be inspired and eager to serve.

"The Commission is comprised of eleven commissioners who bring together diverse experiences from service in the military, public office, on Capitol Hill, and with not-for-profit organizations."

May I suggest to Congress that they themselves set an example of national service by getting the national debt and deficit under control, and generally by governing well?

The members of the Commission sound like a true roster of the best and the brightest - or so I'd assume, because they don't seem to have been chosen for their fame or prominence:

The Honorable Dr. Joseph Heck, Commission Chairman, former Member of the House of Representatives (NV-3)

The Honorable Mark Gearan, Vice Chair for National and Public Service, former Director of the Peace Corps

The Honorable Debra Wada, Vice Chair for Military Service, former Assistant Secretary of the Army for Manpower and Reserve Affairs

Mr. Edward Allard III, former Deputy Director of the Selective Service System

Mr. Steve Barney, former General Counsel to the Senate Armed Service Committee

The Honorable Dr. Janine Davidson, former Under Secretary of the Navy

Ms. Avril Haines, former Principal Deputy National Security Advisor

Ms. Jeanette James, former Professional Staff Member of the House Armed Services Committee

Mr. Alan Khazei, Founder and Chief Executive Officer of Be the Change, Inc.

Mr. Thomas Kilgannon, President of Freedom Alliance

Ms. Shawn Skelly, former Director, Executive Secretariat, U.S. Department of Transportation

(I see the original post already linked to these guys, sorry for the repetition)

Any chance it's going to be called the Heck Commission?

They could start by learning what "comprised" means.

"I say that the government should force the young people of America to pull up their pants and get to work digging in the salt mines, and so forth.

"Of course, the sons and daughters of high party officials will get to be supervisors, except the really retarded ones who will get deferments."

And the ones afflicted by illusory bone spurs?

I have no idea what that means, but knowing your schtick, I can only presume you're referring to some draft deferment procured by a conservative during the Vietnam War.

Ah, I was wrong, it wasn't a conservative, it was President Trump.

Speaking of bones, has it even penetrated your thick skull that in criticizing Mr. Heck and his precious commission, I was also criticizing the President and Congress who authorized it all?

I hear that there will be special categories for wreckers, hoarders, and saboteurs.

One type of mandatory service you don't deal with is compelled service in a federal posse, e.g., an Assistant U.S. Marshal compelling you to help him apprehend those bank robbers holed up with guns across the street (or, more commonly back in the a couple of different days, to help apprehend some fugitive slaves or moonshiners). The statute authorizing such mandatory federal posse service was enacted by the First Congress, which included many framers; the Federalist argues that such service can be compelled under the Necessary and Proper clause; and, as Secretary of State, Madison himself urged that such power be used to enforce a law (the Embargo Act) enacted under the Commerce Clause. The power to compel service in a federal posse is, to be sure, not a power used frequently these days and would generally be of short duration. But it is a power that at least many framers thought the government should have to mandate federal service in work that could be dangerous and, indeed, life threatening. This is more or less irrelevant to your argument against national service on policy grounds, but doesn't your constitutional argument either need to distinguish posse service or explain why those framers who thought it could be compelled were wrong?

Wouldn't the posses be authorized under the militia clause?

Interesting question!

I would think that the Militia clause would authorize some kind of posse-like power by the federal government. But I don't think it quite matches the actual power, which has been thought to involve the "duty of every citizen when called upon by the proper officer, to act as part of the posse comitatus in upholding the laws of his country." In re Quarles, 158 U.S. 332, 335 (1895). Every citizen would have included persons too young, too old, or (in 1789 and 1895) too female to be part of the militia. I suppose you could argue that the act of compelling posse service should be deemed to be enlisting someone in the militia, but that strikes me as stretching terms to avoid the more straightforward conclusion that the Necessary and Proper clause does some of the work here.

Hamilton does discuss the federal posse in the Federalist Paper (No. 29) addressing the Militia clause, but he viewed the Necessary and Proper clause as justifying federal posses: "It would be as absurd to doubt, that a right to pass all laws NECESSARY AND PROPER to execute its declared powers, would include that of requiring the assistance of the citizens to the officers who may be intrusted with the execution of those laws . . . ."

Of course, one defining characteristic of a militia is that the members are volunteers, not under orders of any government until they reach an agreement to become subject to those orders, serving under their own elected officers. You cannot be compelled to join a militia. If you submit to compulsion, you are forced into a posse or army.

The first few dictionaries I checked -- can't say I've checked them all -- don't have voluntariness as a defining characteristic of "militia." Under federal law, all able-bodied males who are at least 17 but under 45 are members of the militia, if only in many cases the "unorganized" militia.

On the other hand, Longtobefree, you may be right that service in a militia, or posse for that matter, is de facto voluntary even if de jure compulsory, as the fictional Will Kane found out.

The "High Noon" scenario where one might want a posse or militia, an area under attack isolated from timely response by the government's volunteer professional fighters, is not one that would arise too often in modern times, though there are still situations where it might, (think of, for example, the mass shooting in that rural Texas church).

OK, if this is an example of compulsory civilian service, then it would go alongside jury service as things for which there's a common-law tradition.

The question of compulsory federal *military* service seems to me to have been addressed in the militia clauses, which specify a Congressional power to provide for federalizing the militia to fend off invasions, put down insurrections, or enforce federal law.

Of course, these militia clauses would be superfluous if the Constitution already covered the issue through a general power of military conscription, as current dogma holds.

I would prefer to think that the Framers didn't insert redundant and misleading clauses in the Constitution, but obviously I have against me the unanimous weight of the Supreme Court, and numerous federal conscription laws in history.

Um, no? The Thirteenth Amendment didn't exist when those framers did.

Yes, I was thinking primarily of the scope-of-power argument rather than the 13th Amendment one, but I neglected to say that.

On the 13th Amendment, Prof. Somin's argument against Butler, if correct, would I think apply mutatis mutandis to posse service.

The two arguments seem to be presented as independently sufficient, though there may be some bleed over of the scope-of-power argument into the 13th Amendment one, as coloration though not outright premise.

>explain why those framers who thought it could be compelled were wrong?

But see the Alien and Sedition Acts

1. I think in exceptional circumstances a necessity argument could be made in favor of involuntary servitude in the form of military service. E.g., if the country is under such a severe and immediate threat that not forcing people into military service would result in the entire country, including those not wanting to be in the military, being destroyed by the enemy.

2. Regardless of any other arguments, it's always unfair, unconscionable, and unconstitutional to selectively force only the youngest and most politically powerless persons into military service.

Regardless of any other arguments, it's always unfair, unconscionable, and unconstitutional to selectively force only the youngest and most politically powerless persons into military service.

It's got nothing to do with being politically powerless, it's all to do with being physically fit, active, strong and full of stamina. Military service is active physically demanding work. That's why it's done by young men. Not by old women. In fact, immediately before the Great War, the German Army regarded only the youngest cohort of German manhood as fit for military service. Even those in their mid twenties who had completed their military training were regarded as too old for front line service, and only good as reserves.

It's got nothing to do with being politically powerless, it's all to do with being physically fit, active, strong and full of stamina.

This is only the case if the draft is virtually universal.

When it's not, when there are all sorts of ways to dodge it, or, if going into the military is unavoidable, to maneuver into relatively safe spots, far away from combat, it has a lot to do with political power, wealth, connections, and so on.

I agree.

One way to encourage the socially and financially "upper' classes not to dodge a draft is to make political power conditional on prior miitary service. (See my comment below on the traditional connection between military service and citizenship.)

eg no one gets to be a Senator unless they've served for three years in the military. Or you get a 5% discount on your income tax if you've served. It's hard to believe anyone could be against that 🙂

A Senate composed of people who've served, in their youth, in the military has got to be less contemptible, on average, than a Senate composed 75% of lawyers.

Lee,

I see a few problems with this.

First, I don't think there is a correlation between having served in the military and being a good legislator. Even if you take military service as an index of some version of patriotism, which I don't, there are stupid patriots as well as smart ones.

Second, some people are unable to serve, for physical reasons. And as soon as you make an exception for them you are going to get an epidemic of bone spurs.

Third, the military doesn't need everyone, or even most people, so you are limiting the pool for no reason.

Fourth, do we want our armed forces heavily populated by the politically ambitious?

So no.I don't think your idea really works.

Even if you take military service as an index of some version of patriotism

No, I'd take it as a proxy for loyalty - as it has been taken in older polities. Of course it's not a perfect proxy.

In any event, I'm not sure cleverness is the prime requirement in a legislator. OK, extreme stupidity isn't a plus, but Nancy kinda spilled the beans on legislative sausage making - the staff read the Bills, the legislators take their word for what's in them. (Apparently Rod Rosenstein doesn't read FISA applications, and no one disputes that he's very clever. He presumably thinks his time is better spent on other things. Ditto Senators.)

I wasn't planning to make any exception fo bone spurs. You don't serve, you don't qualify. I'm not worried about limiting the pool. Clever folk with bone spurs can run for the House.

do we want our armed forces heavily populated by the politically ambitious?

It's not going to be heavily populated though, because there are very few slots in the Senate. It's like that "most terrorists are Muslims" / "most Muslims are terrorists" confusion. It's not [if you're in the army you must be politically ambitious} it's {if you're politically ambitious you must we willing to serve in the army (or navy etc}

It also has much to do with just starting out life as an adult, with far fewer ties than if you let people start a career and family for five years, then conscript them and disrupt everything.

Once again missing the point. If the people are not willing to volunteer to save the country under those circumstances, then the political leaders who would force them against their will, to the point of threatening prison and death, are just slavers.

And if the people are willing to help defend the country, then enslavement is unnecessary.

There is no compromise, no middle ground. You cannot come up with any hypothetical where the people want to save the country but are not willing to save the country.

Military service has traditionally been a duty, directly connected with citizenship. Military technology has moved on, so the purely military value of citzens-in-arms in doubtful. But there's a long history of unfortunate political consequences from relying on professional armed forces, and only a lawyer could imagine that an apolitical military, always ready to obey the command of civilian politicians, is a given. It's not. If you're going to have a standing army, made up of professionals, you'd better have an excellent social and cultural infrastructure to keep the military and the civilians on the same page. Once you get the citizens looking on the military as "them", the military is liable to return the compliment.

Hail Caesar!

Meanwhile, while worrying about military coups, we've experienced repeated coups d'etat from the judiciary - no more legitimate than a coup by a junta of bemedaled colonels.

From the other article - - - -

Qualified immunity means "even actions that violate the Constitution do not lead to liability,"

So who cares anymore about constitutionality?

We seem to be dealing with shades of gray here. The headline says unjust as well as unconstitutional. So let's talk about just, and not get too much bogged down into legalese.

1. Howcum it's okay to compel military service on the say-so of those who want to save Vietnam from the godless commies (for example)?

2. The taxes I pay are equivalent in some real sense to time taken out of my life. How do those differ in any moral sense from actual conscription into a CCC? Does it have to be 24x7 before it counts?

3. If conscription were applied to 100% of the population, would it thereby become just and acceptable?

It would be useful if it were possible to put some crisp edges on where we cross the line into injustice.

I agree with your post in terms of National Service, but not the draft.

But I'd like to point out that due to an editing error the paragraph wherein you accuse Trump of plotting to make all of his opponents slaves on a chain gang was inadvertently left out.

I agree with Charlie Rangel. We are way to cavalier about going to war in this country. I would like the Congressmen and Presidents to consider that if they go to war their family members may have to serve. Any war that last more than three years should require a draft. Even volunteers should not serve more than two combat tours in the same war.

I oppose universal service as a policy matter, but given that a military draft is constitutionally unassailable, it seems that universal service could be structured on that basis. That is, enact universal conscription and give all a few weeks of basic training. Thereafter, allow individuals to opt to fulfill their military obligation by choosing one of the "other services" (Peace Corps, etc.) while being at all times subject to immediate military service, should the need arise. In short, it would create universal "reserve" status.This structure, I think, would be more constitutionally defensible than use of a tax or the commerce clause. From a policy standpoint, it increases military preparedness by being able to "draft" from a pre-qualified and at least somewhat pre-trained pool, and would seem to fall within Congress' authority to raise armies, and further the constitutional value of making "a well-regulated militia" available to the states. As I said, however, I oppose this as a policy.

Thereafter, allow individuals to opt to fulfill their military obligation by choosing one of the "other services" (Peace Corps, etc.) ......... would seem to fall within Congress' authority to raise armies

These seem contradictory to me. It seems very doubtful to me that Congress's authority to raise armies extends to Peace Corps and other non military institutions. The point of military service is to assist in the military defense of the nation. This is not at all the same as assisting in the economic development, social harmony, ecological preservation or whatever of the nation. Nor - contrary to frequent assertions - is it satisfied by a readiness to die for your country. The essental point about military service is the readiness to kill for your country. Services to your country that do not involve lethal force, or the threat of it, or preparations for it, are not the business of "armies."

Right. But that is where the military preparedness comes in. Universal conscription would provide more folks than we need militarily, absent a major conflict.The military already has doctors, nurses, lawyers, engineers, mechanics, intelligence analysts, IT departments, purchasing agents, inventory managers, secretaries, clerks and translators, not to mention chaplains, most of whom will never be called upon to kill for their country and many of whom have not even been trained to do so. The military participates in disaster relief, and the Army Corp of Engineers has partial responsibility for enforcing the Clean Water Act, builds domestic damns for hydro-power and flood relief and is involved in public works in foreign countries. Sounds pretty Peace Corps-like and environmental to me. The Peace Corp has always been sold as increasing our security by creating goodwill towards the U.S.. In short, I think your distinction breaks down under scrutiny in terms of both the varied activities and the personnel of our current "Armed Forces." Again, I don't think it would be good policy, but I think the structure would be constitutional. The personnel in "other services" would be just as available to a war effort, arguably more so, than many existing military personnel, and both foreign goodwill and domestic strength has always been considered a part of our national security. One would need a better place to draw the line.

Are federal subpoenas for depositions in civil cases constitutional under the theories of the post with respect to non-party, non-expert witnesses?

I do not favor "involuntary servitude" or "forced labor" but they are not the same thing. Purely from a constitutional interpretation point of view "servitude" implies a habitual or extended service. Forced labor does not. So forced labor for a couple of weeks to, say, dig fortifications in the path of an invading army, does not add up to "servitude" - five years probably does.

Recalling my personal life experience, the quickest way to compel America to make up its mind whether a war is justified or not is to ship massive numbers of conscripted troops to it. Now conscription the way Abraham Lincoln did it was pretty cheesy (meaning socially unfair) and Lyndon Baines Johnson did not do much better. I've always looked at the Peace Corps as being the old missionary impulse only without God or even, anymore, without any particular idea that the American way of doing anything is superior. Peace Corps members are just some miserable place to prove they care, that's it. The main thing the experience does for liberals intent on a career in government is give them a resume enhancer comparable to military veteran status.

"Now conscription the way Abraham Lincoln did it was pretty cheesy (meaning socially unfair) and Lyndon Baines Johnson did not do much better."

And if you consult the national service folks, they'll say that future drafts will not only avoid the abuses of the past but actually unite social classes instead of dividing them like previous drafts.

Step 1) encourage youth to take out crushing "loans" from the government;

Step 2) offer to forgive a portion of those loans for each year of "public service" (i.e., selected non-profit or, of course, for the government itself)

and if that doesn't work:

3) make other benefits contingent on such service (ala various benefits being contingent on registering for the draft)

As a side benefit, the scions of great families will get automatically excluded; they don't need the loans.

You've sidled up to the cliff, why not jump and make voting conditional on prior service?

Professor Somin's argument is remarkably similar to the winning argument the city of Paris made when it obtained a court injunction against the rats that had infested it in the Middle Ages. The presence of the rats was unnatural and unjust; it violated the good denizen's natural rights. Not only was it most unfair, it was most foul. The court duly found the rats to be in the wrong and ordered them to vacate the city forthwith.

While one would think that an argument based on natural rights and natural justice ought to be a slam dunk win, the problem is that it wasn't in this case. It turned out that the rats flagrantly disrespected justice. An argument based on pure justice simply didn't work for them.

It's not clear it will work here either.

To my mind, this refutation represents massive overkill. Mandatory public service would be immensely expensive and, more to the point, immensely unpopular with the poor kids who would be expected to undergo it. I served in the old draft army that fought in Vietnam. In the year I entered the army, 1968, there were 3.5 million service members, a post-WWII record, compared to about 1.3 million today. Today's "birth cohorts" average around 4 million a year. Where are the bases, the training facilities, barracks, mess halls, etc., etc., etc., to house and feed such hordes? Furthermore, when I was in the army it was still basically a working class institution. Today's middle-class kids would not accept such a "simple" life.

It won't happen.

A mother of several young children is their daily caretaker; the father works mostly out of state and is only home on weekends at best. Mother is assigned to jury duty about two hours away, and is informed that most likely she will be sequestered there, and that the case (involving multiple defendants in a multi-year prison guard drug conspiracy) will take two to four weeks in trial and deliberation.

She's the only person getting the grade-school kids up in the morning, feeding them, getting them to school and back, and running the household. The family does not have means to hire someone to take over the house and children for a month. There are no relatives to come do it.

Mother is told that this is normal -- being a parent is no excuse, and she must report for jury duty and will not be dismissed.

How is that fair?

Enslaving the other half of the country is not a solution to enslaving half of it.

This is not particular to America, it's true in any polity. Young men become soldiers and when they get older they become civilians.