The Volokh Conspiracy

Mostly law professors | Sometimes contrarian | Often libertarian | Always independent

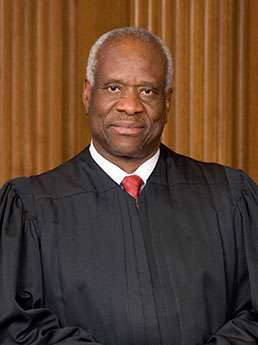

Abortion, Clarence Thomas, and the Commerce Clause

Cornell law professor Michael Dorf asks whether Clarence Thomas would vote to strike down federal laws restricting abortion, on federalism grounds. The answer might well be yes. But the issue would have to be presented to him in the right way.

The likely replacement of Justice Anthony Kennedy by Brett Kavanaugh, or some other new, more conservative Supreme Court justice indicates that the Court is likely to be more willing to uphold restrictions on abortion than in the past. Even if Roe v. Wade is not completely overruled, its scope is likely to be narrowed. While most commentators suggest that this change would give the states greater autonomy on abortion policy, Cornell Law Professor Michael Dorf notes that Congress - if it remains under GOP control - might adopt new abortion restrictions of its own. Indeed, a GOP-controlled Congress previously passed the Partial Birth Abortion Act of 2003, and the House of Representatives has passed a bill that would ban abortion after the 20th week of pregnancy (though it is unlikely to get through the Senate). Even if the Republicans do not maintain control of both houses of Congress in the upcoming fall election, they will likely have it again in the short to medium-term future, given the closely divided nature of American politics in recent years.

Federal restrictions on abortion pose a much greater threat to the pro-choice cause than state ones do, because they cannot be as easily avoided by traveling to another jurisdiction to get an abortion in an area where it is legal. Going abroad to get an abortion is often much more difficult than going to another state.

Should Congress adopt new federal restrictions on abortion, Dorf suggest that Justice Clarence Thomas - the most conservative member of the Court - might become the unlikely savior of abortion rights:

To prevent that outcome, pro-choice voters must make their voices heard in congressional elections, but if they fail to do so in time, there is one person who could rescue abortion from restrictive nationwide laws: Justice Clarence Thomas might join the Supreme Court's four Democratic appointees to invalidate such laws.

Justice Thomas is a highly unlikely hero of the pro-choice movement. He raised eyebrows when he told Senators during his 1991 confirmation hearing that he didn't "remember personally engaging" in discussions of abortion as a law student in the 1970s. And since his appointment, Justice Thomas has never voted to invalidate any challenged abortion restriction. Just two years ago, in a case from Texas, he wrote: "I remain fundamentally opposed to the Court's abortion jurisprudence."

Yet Justice Thomas has also indicated that he would like to see the power of Congress rolled back to its eighteenth-century foundations. Hence, in a 2005 case, he voted to strike down a federal law banning the local cultivation and use of marijuana, splitting with fellow conservative Justice Antonin Scalia. Most tellingly, when he joined the Court's majority upholding the federal Partial Birth Abortion Ban Act in 2007, Justice Thomas emphasized that the Court's ruling rejected a challenge based on the right to abortion but left open the possibility that the law might not be "a permissible exercise of Congress' power under the Commerce Clause."

Would Justice Thomas really strike down federal legislation restricting abortion? We may soon find out.

I am not convinced that Thomas "would like to see the power of Congress rolled back to its eighteenth-century foundations." His Commerce Clause opinions indicate that he would like to reconsider expansive modern interpretations of the Clause, but also that he recognizes some erroneous precedents might be too entrenched to overrule. As he put it in a concurring opinion in United States v. Lopez (1995), "Consideration of stare decisis and reliance interests may convince us that we cannot wipe the slate clean" in this field. But there is no doubt Thomas would be happy to roll back federal power a great deal relative to where it is now. Gonzales v. Raich, the medical marijuana case mentioned by Dorf, shows he is willing to do so in even in cases where the federal law in question is one favored by many conservatives. And, as Dorf notes, Thomas' concurring opinion in the 2007 Partial Birth Abortion Act case indicates that he is open to considering such a move when it comes to federal abortion regulations.

Thus, Dorf is right to counsel pro-choice groups to raise federalism arguments in future cases challenging federal abortion regulations. If they are not raised, Thomas (and perhaps other justices) will not consider them. In addition, they would be well advised to argue for the overruling of Raich. If Raich is left intact, its extraordinarily broad interpretation of federal power to regulate interstate commerce is easily enough to encompass nearly all abortions. Raich held that the Commerce Clause gives Congress the power to regulate virtually any "economic activity" defined as anything that involves the "production, distribution, and consumption of commodities." That's how the Court was able to use the Commerce Clause to uphold a federal ban on the possession of marijuana that had never crossed state lines or been sold in any market (even an intrastate one). Nearly all abortions involve the "consumption" and "distribution" of commodities, such as medical supplies. Thomas wrote a forceful dissent in Raich, and would likely be happy to vote to overrule it. But he has also stated that he will not vote to overturn a precedent unless one of the parties to the case asks him to do so. Pro-choice litigants challenging federal abortion regulations should take him up on that invitation. They could potentially end up with a decision in their favor under which four liberal justices vote to strike down a federal abortion regulation on individual rights grounds, while Thomas (and perhaps some other conservative justices) vote to strike down based on federalism considerations.

For what it is worth, this advice to abortion rights advocates is not motivated solely by my longstanding desire to see federal power rolled back. While I have doubts about the validity of Roe v. Wade, I am also generally pro-choice, and I do not want to see federal restrictions on abortion (and also oppose most state restrictions, as well).

That said, there is good reason to get rid of Raich even aside from the potential effects on abortion. For reasons I explained in this article about the case, it is one of the worst Supreme Court federalism rulings ever. From an originalist point of view, the idea that the Commerce Clause gives Congress virtually unlimited authority to ban the possession of any product of any kind is highly implausible. As recently as the 1920s, federal Prohibition of alcohol was general understood to require a constitutional amendment, because it was beyond the original scope of federal power. From the standpoint of living constitutionalism, the idea that such enormously broad federal authority is necessary, is also highly questionable - particularly in a complex and diverse society like ours.

Overruling Raich is one example of how both right and left stand to gain from tighter enforcement of constitutional limits on federal power. Prominent liberal scholars such as Heather Gerken and Jeffrey Rosen have already urged fellow progressives to reconsider federalism. Perhaps the abortion question will encourage additional rethinking on along these lines. For their part, conservatives should also strive to avoid "fair weather federalism," an area where many have fallen short in the Trump era.

Editor's Note: We invite comments and request that they be civil and on-topic. We do not moderate or assume any responsibility for comments, which are owned by the readers who post them. Comments do not represent the views of Reason.com or Reason Foundation. We reserve the right to delete any comment for any reason at any time. Comments may only be edited within 5 minutes of posting. Report abuses.

Please to post comments

"I am also generally pro-choice ..."

If one is pro-choice, then 'generally' cannot apply here. That is, if you believe that the right to an abortion is simply a matter of a woman's 'right to choose,' then no other concern applies. And so, if a woman chooses a third term abortion, that's her right. If she chooses to abort a female fetus to have a male later, that's her right. Once yo accepts the term 'pro-choice,' you have to live with the logical implications. Which is the whole point of using the term.

On the other hand, if, by pro-choice, you mean pro-abortion (with caveats), then man up and say pro-abortion.

It's more nuanced than that.

You can be pro-choice as you described but be or not be willing for taxes to pay for the procedure; should minors be allowed to get the procedure without parental permission and/or notification; where to allow or limit abortion clinic protests, etc.

It's a lot more than just the procedure.

Further, you're not required to be "pro-choice" at 35 weeks just because you're pro-choice at 5 weeks.

^This

I used to be strict pro-life . But as appealing as it is to say "life starts at fertilization" , there are still gray zones. Example: frozen embryos left over from IVF procedures . They are fertilized , but I would not consider them " a life" any more than unfertilized eggs and sperm. So there is no bright line between gametes and human beings. The line is fuzzy.

So where do we draw that line? I would certainly trust the mother ( and father if involved) , and not the government when it comes to that decision. Hence pro-choice.

I agree with this.

I was similarly strictly pro-life when I was younger and the lack of clarity in this "when does it become a life" question is the reason I've backed off a bit. I still shy away from going full pro-choice, because while I can agree to let someone make their own decision to abort at 5 weeks, 35 weeks is a separate matter (I mean this is getting awful close to partial-birth). For me, we're far past that "it's a life" line at that point, though I have no specific moral ground to stand on if someone else disagrees.

I even read once where a psychologist argued that children below the age of 2-3 don't yet have autonomy/agency and therefore are intellectually more like their former fetal identities than they will be at the age of, say, 5. This wasn't pointed out specifically to make the argument that post-birth abortion (up to 2 or 3 years old) would be justified, but just to point out that these biological milestones that can be used to define "now it's a life" continue happening after birth, so they COULD be used by someone to make the argument to allow pro-choice to include young children. I would hope that most of us would consider such "abortions" to be clear murders.

So where do we draw that line? I would certainly trust the mother ( and father if involved) , and not the government when it comes to that decision. Hence pro-choice.

Because the interests of the parents and the interests of the fetus are never in conflict?

Yes, people don't generally speak it extreme literal ways like that.

Regardless of how one personally feels about abortion and abortion politics, this is semantic ridonkulousness.

1) Many people who identify as "pro-choice" (and I would wager the vast majority) support some limits on that choice, and do not object to society/government imposing restrictions. There's certainly an open debate about where to draw the lines (20 weeks? 24 weeks? quickening? elsewhere?), but not about the propriety of line-drawing itself.

2) There definitely exist people who are "pro-choice" (in the sense of supporting a woman's right to choose, in circumstances limited by society/government as per #1), who are not personally "pro-abortion" (in the sense that they would not personally choose to have one in some or all circumstances).

Trying to unilaterally redefine commonly-understood terms to fit your own personal agenda is pretty darn weak trolling.

The LP platform addressed this in 1972. The Supreme Court ran with it but tacked on an extra week of protection of women's individual rights against doctor-killing lynch mobs. Canada took this a step further and struck down ALL efforts to use service pistols to threaten the lives off women and physicians. LP Canada has no mention off abortion in its platform. It's a won battle. Dems are just as superstitious about electric power plants, and THAT plus our spoiler votes lost their goons the election.

"Trying to unilaterally redefine commonly-understood terms to fit your own personal agenda is pretty darn weak trolling."

without getting into the abortion debate isn't this exactly what the pro-choice forces have done? I remember when the debate was anti abortion or pro abortion. Over the years the groups who are now pro-choice kept pushing for the terminology we now have.

I'm pro-abortion in the sense that I support the state not legislating away a woman's ability to get an abortion, especially early in pregnancy.

Calling oneself "pro-choice" while at the same time supporting the Federal Government's right to decide for me what kind of health insurance I must buy, what coverages it must have, whether or not I can accept a job that, in the Government's view, doesn't pay me enough or doesn't offer enough non-wage benefits, or any number of other programs that restrict my individual right to choose, is just dishonest. If you think that the right to choose is limited to women, applies only to their uteri, and ends at the outer limits of that uterus, you are NOT "pro-choice", you are just pro-abortion. You like to use misleading and dishonest labels, like "pro-choice", "liberal", and "progressive" because they sound pleasant and have a positive emotional impact, even if they are complete canards.

Personally, I am generally pro-choice, but by that I mean not only that women should have the right to choose whether or not to carry a fetus to term, but that the right to choose, free from government interference, covers a much broader range of subjects, including economic and property rights, than just a woman's right to reproductive freedom. When you get a much broader view of just what choices the government needs to keep the hell out of, one which doesn't end at the outer limits of a woman's uterus, THEN, and ONLY THEN may you use the label "pro-choice" without simply being a lying statist.

By your logic, one of the following must be true:

*You do not believe that government should punish murder

or

*You believe that a fetus is not a human being worthy of any rights at all, until the magical moment it is born.

Which is it?

JonFrum"If one is pro-choice, then 'generally' cannot apply here"

Well, I'd advise that a large proportion of people in the general population refer to themselves as "pro-choice" but absolutely do /not/ believe in abortion at any time and for any reason. So you should take it up with them.

According to Pew, there's a 57 to 40% majority in favor of abortion being legal in "most or all cases" as opposed to illegal in all or most cases.

But the proportion actually calling themselves pro-life and pro-choice is tied (48% each), according to Gallup data.

And the Pew survey finds only 25% saying it should be legal in /all/ cases.

What are those cases?

Well, there's timing. Another Gallup (2018) survey found that in the first trimester, 60% said abortion should "generally" be legal (down six points from 2003). But only 28% chose that answer for the second trimester, and only 13% in the third trimester. Well, indeed.

(continued)

(continued)

To confuse things more, Gallup finds that large majorities favor legal abortion if the woman's life is endangered, the pregnancy was the result of rape or incest, or the child would be born with a life threatening illness. A simple majority support abortion if the child would be born mentally disabled -- but that's in the first trimester. Third-trimester abortions receive majority support only for the life of the mother and a rape/incest pregnancy. Only 20% support 3T abortion if "the woman does not want the child for any reason."

(The General Social Survey gets comparable results, though they don't have an abortion timing question. Majorities oppose abortion for reasons of poverty, not wanting to marry the man, not wanting anymore children, or for just "any reason" )

So roughly sixty percent of "pro-choicers" need to man up and call themselves "pro-abortion (with caveats)." I wouldn't disagree, but groups such as ThinkProgress trumpet the fact that sizable majorities do not support overturning abortion "completely" as indicating that 69% of the nation is pro-choice. So take it up with them, too.

According to Pew, there's a 57 to 40% majority in favor of abortion being legal in "most or all cases" as opposed to illegal in all or most cases.

This is contradicted by Gallup. It probably depends on how the question is asked. According to Gallup, only 43% say that abortion should be legal in most or all cases, while 53% say that abortion should be legal only in a few or in no cases. Furthermore, according to Gallup, 48% identify as "pro-choice" and 48% identify as "pro-life."

According to a Marist poll, 59 percent support a ban on abortions performed after 20 weeks of pregnancy, with an exception of when the life of the mother is at stake.

What Trump era policies have caused conservatives to "fall short" of adhering to 10th Amend. principles? Possibly sanctuary cities/state litigation under the tax/spend power, and marijuana enforcement. I believe both are DOJ-initiated policies.

One reason neither left nor right want the constitution to actually limit federal power: it decentralizes power, makes scare tactics and raising money more difficult, and lobbying less profitable. We should phase out every unconstitutional program.

Ignoring the 10th Amendment goes back way before the Trump administration. And it's been a long-standing bi-partisan abuse.

Permit me to complicate that with one point. The corporate right, meaning most Republicans, is of two minds about federalism, depending in large measure on which business models particular corporations use. Corporations with material interests which are broadly interstate sometimes like federal power, for its ability to simplify marketing across the entire nation. Car companies, for instance.

By contrast, corporations which either sell locally, or extract resources locally, prefer less federal power?because their policy interests are more cheaply and reliably bought from state legislatures. Utility companies, for instance.

The Commerce Clause isn't all that's implicated in the case of permissive abortion laws. The federal government, one might argue (I certainly do), can step in if a state basically declares a human being an outlaw without a trial. Due process concerns.

Plus, at minimum Congress ought to be able to forbid anyone from using the channels of interstate commerce to facilitate abortion.

I dunno, could the federal courts step in if a state government created rules allowing killing another human being (just think of any adult human being for the moment) in more circumstances than is typical? More permissive self defense laws? Lower burdens for hospitals to remove life support? I'm not sure that works.

Yes. Federal courts did hear a case regarding removing life support. Remember Terry Schiavo? That was, after an act of Congress granting jurisdiction even though a state court had already ruled, a federal case about the state permitting her doctors to stop feeding her based on her ex-husband's say-so. (Although the court did not get to the merits).

Now, some anti-substantive due process people have held that any time a state follows its established laws, it is not violating the due process clause, no matter what. That is not the law, though, and Justice Thomas does not believe that even as an original matter.

Husband. Now widower. They were not divorced.

"Plus, at minimum Congress ought to be able to forbid anyone from using the channels of interstate commerce to facilitate abortion."

Abortion is legal so . . . exactly what would they be forbidding?

Isn't that like trying to ban hand gun magazines?

Except for the explicitly enumerated vs pulled out of a judges' ass aspect, yeah.

I'm pretty pro-life, and I don't see a legitimate commerce clause handle here. Maybe 14th amendment, though.

"Except for the explicitly enumerated vs pulled out of a judges' ass aspect, yeah."

I don't get how people can make this argument when the Constitution explicitly tells you not to do that.

The Constitution explicitly tells us there are rights that aren't enumerated, and that they aren't enumerated doesn't mean they aren't protected. That isn't the same thing as saying that judges are entitled to invent new rights with no basis in American traditions, in fact contrary to them.

The 9th amendment was only supposed to protect pre-existing rights it didn't occur to anybody to bother listing. The right to travel, for instance; It's not enumerated, but it existed at the time the 9th amendment was written and ratified. The right to self defense, ditto.

So, if you can demonstrate that there was a widely respected right to abortion in the late 1700's, early 1800's, you've got a point. Not otherwise.

The 9th amendment was only supposed to protect pre-existing rights it didn't occur to anybody to bother listing. The right to travel, for instance

My understanding is that the purpose of the 9th Amendment was not to give constitutional protection to various unenumerated rights. As Justice Black put it in Griswold v. Connecticut, the Ninth Amendment "was intended to protect against the idea that 'by enumerating particular exceptions to the grant of power' to the Federal Government 'those rights which were not singled out, were intended to be assigned into the hands of the General Government.' " For him, the 9th Amendment "was passed not to broaden the powers of this Court . . . but . . . to limit the Federal Government to the powers granted."

James Madison's explanation in the First Congress also negates the implication that there are constitutional rights in addition to those expressly stipulated for in the Constitution. If the guarantees of the Bill of Rights, he said, would be incorporated in the Constitution, the "independent tribunals of justice . . . will be naturally led to resist every encroachment upon rights expressly stipulated for in the Constitution by the Declaration of Rights." 1 Annals of Congress 439

Even Lawrence Tribe, no originalist, "points out the impossibility of viewing the Ninth Amendment as the source of rights." 64 Chi.-Kent L. Rev. 131

I don't see the Ninth Amendment as a source of rights, but it has to mean something. Brett's explanation comes closest to what I think about it, though I wouldn't tie a proposed fundamental right so strictly to what people 200 years ago would have thought about it now. More to come after work.

I don't see the Ninth Amendment as a source of rights, but it has to mean something.

Yes, it means something. It means that the federal government was limited to the powers granted, and couldn't argue that the failure to deny them other powers implied a granting of those other powers.

In any event, because certain nonenumerated rights are "retained by the people," it does not follow that federal judges are empowered to enforce them. In Federalist No. 82 at 534 (Mod. Lib. ed. 1937), Hamilton stated, "the states will retain all preexisting authorities which may not be exclusively delegated to the federal head." In short, what was not delegated (enumerated) is retained.

Women having the power to control their bodies and a broader ability to make decisions with others regarding deciding when to add a new member of the family has a "basis in American traditions" and slavery involved robbing women and the couple as a whole of said liberty.

In 1791, abortion was a well recognized choice as was means of contraception that is part of the wider right at issue. There is no "only as understood at the time of this writing" clause in the 9A, so a growing understanding that some unenumerated liberty is necessary is both possible and good constitutional policy. The rational men of the time knew that understandings, including of rights, would develop as new facts and experiences occurred.

The rational men of the time knew that understandings, including of rights, would develop as new facts and experiences occurred.

No, the rational men of the time believed that the only rights protected by the constitution were the rights specified in the constitution. James Madison's statement in the First Congress (that I referenced above) negates the implication that there are constitutional rights in addition to those expressly stipulated for in the Constitution.

It is true that the 9th amendment mentions certain unenumerated rights "retained by the people." But where does it say that the federal judiciary is empowered to enforce these rights? The fact that Amendments One through Eight were meant to limit the powers of the federal government militates against a reading of the Ninth that would confer unlimited federal judicial power to create new "rights." As Hamilton put it, "the states will retain all preexisting authorities which may not be exclusively delegated to the federal head."

The constitutional scheme that the founders had in mind was not a system under which the federal judiciary was tasked with protecting rights but not told what those rights were. The purpose of the Bill of Rights was to limit the federal government, not to invite the federal judiciary to assume unlimited authority.

The constitutional scheme that the founders had in mind was not a system under which the federal judiciary was tasked with protecting rights but not told what those rights were. The purpose of the Bill of Rights was to limit the federal government, not to invite the federal judiciary to assume unlimited authority.

swood1000, that was nicely put.

If the abortion issue is really about choice then why do we limit the choice to women? Why don't we allow men to have the choice to surrender all parental rights and responsibilities? Why do women have the choice to avoid the complications of an unplanned pregnancy but not men? Why do we send people with guns to force men to pay child support?

Why do we send people with guns to force men to pay child support?

Because men caused the child.

Why do women have the choice to avoid the complications of an unplanned pregnancy but not men?

Because pregnancy endangers women's health but not men's health, though the pro-life argument is that abortion is a greater danger to the health of the baby, and since women had it entirely within their power to avoid pregnancy completely, once they voluntarily cause a third person to become involved they should not be heard to say that only their own interests and preferences should be considered.

"because men caused the child."

Only in the case of rape. Otherwise both shared in causing the child, in which case it is reasonable that both should share in the decision to end the pregnancy.

As to endangerment of health, most pro-life people agree that abortion to preserve the life of the mother is allowable.

What you miss in all of this is any idea that the fetus is a human being. A fetus which is born prematurely cannot be legally killed. But a fetus of a later gestational age can be killed for no reason at all.

That is profoundly anti-libertarian, unless the libertarian believes that some magic happens when the fetus is born.

This "people with guns" bit gets tiresome. The guns aren't there to force payment of child support. Obeying the law is supposed to do that. The guns are there to counter defiance of the law, no matter which law is in question.

That isn't the same thing as saying that judges are entitled to invent new rights with no basis in American traditions, in fact contrary to them.

The pro-majoritarian implications of that notion about traditions seem counter to the countervailing ideal of individual rights. Presumably whatever gets the approval of tradition is unlikely to require defense as a matter of right.

Abortion already is regulated including making certain things about it illegal -- Congress already banned a specific procedure and the Supreme Court held it did not violate the liberty involved in Planned Parenthood v. Casey (at least if exceptions were left open for special cases where it may be necessary for health).

So, not sure what the question is. If interstate commerce is being legislated, sometimes things are not allowed though they need not be absolute about it.

This is a very popular opinioon among conservatives on the Internet who haven't thought a lot about jurisprudence, but there's a reason basically no conservative legal scholars or legal minds endorse it. It would require overturning DeShaney and imposing a duty to protect into the Due Process Clause.

And despite its effect on abortion laws, that would be a boon for liberals overall. It could make restrictive welfare and health care rules unconstitutional. It could require strong OSHA rules. It could lead to an invalidation of overzealous self-defense laws and even libertarian gun laws. It would open the door to all sorts of "state X is not doing enough to protect lives" arguments.

It would create what philosophers call an enforceable "positive right"- a right to have the state intervene to protect your life against some private action. And it could even be extended beyond protecting life, to liberty and property as well. And that's definitely a boon for the left.

"This is a very popular opinioon among conservatives on the Internet who haven't thought a lot about jurisprudence"

What's an "opinioon"?

If someone doesn't think quite like you, it's not necessarily because they didn't think through their opinions. Talk about a boon for the left!

The prohibition on arbitrary outlawry has a very specific history dating back to the Magna Carta. But I'm sure if you think differently than I do, you simply haven't thought about it enough.

Let's see if you can identify the source of the following quote: "If this suggestion of (fetal) personhood is established, the appellant's case, of course, collapses, for the fetus' right to life would then be guaranteed specifically by the (Fourteenth) Amendment."

If acknowledging a constitutional right for innocent human beings helps the left, then my conclusion would be that the left must have some redeeming features.

Now, if the government had specifically decided that DeShaney's (sp?) guardians should be legally authorized to kill him, that would have been a deprivation of the right to life without due process of law. It would have been illegal outlawry. Have you thought about that angle enough to agree with me?

Obviously, Eddy did not go to law school in the 80's or 90's.

We middle-aged lawyers all know the DeShaney (sic) case

..."Poor Joshua!"

As I recall, that case was about whether the government had a responsibility to step in while the abuse was ongoing. It didn't involve the government trying to *legalize* poor Joshua's maltreatment or giving his guardians a get-out-jail-free card after they committed their crimes.

Hmmm...it seems dad got 2 years for crippling Joshua, who died some years later.

The point is, under current law due process does not imply a duty to protect. State governments aren't required to prevent private actors from depriving people of their lives without due process.

Reinterpreting the 14th Amendment to imply such a duty to protect is a can of worms that could not be limited to abortion.

And your law-action distinction is a distinction without a difference. I am sure no "14th Amendment prohibits liberal abortion law" person would accept that a state would have the right to pass a law banning abortion and then just refuse to enforce it and allow abortions to go on.

Perhaps the Equal Protection is implicated and DeShaney can be left alone? In particular assuming the fetus is a person as defined in the Fourteenth Amendment, would a state violate the Equal Protection clause if it punished the murderers of persons except when the victim was a fetus?

They didn't refuse to enforce the law against DeShaney's dad, they locked him up.

The case was about intervening while the abuse was going on. A parallel legal theory would involve your paranoid fantasy about what prolifers want - monitoring pregnant women to make sure they're not planning abortion.

Just to repeat - if they lock up the offender, consider the possibility that the victim wasn't arbitrarily outlawed.

What part of "No persons born..." is unclear?

"All persons born *or naturalized* in the United States, and subject to the jurisdiction thereof, are citizens of the United States and of the state wherein they reside. No state shall make or enforce any law which shall abridge the privileges or immunities of citizens of the United States; nor shall any state deprive any person of life, liberty, or property, without due process of law; nor deny to any person within its jurisdiction the equal protection of the laws."

I'm not sure what you're suggesting...you're not a person until you're born or naturalized?

"I'm not sure what you're suggesting...you're not a person until you're born or naturalized?"

I don't know if Hank is suggesting it, but I will be clear that a new person comes into existence when born alive. The "*or naturalized*" part of the 14th Amendment as quoted is probably ambiguous grammar, as certainly a person born outside of the United States is a person at birth.

So, yes, you are not a person until born. As far as I can tell, it has always been that way.

Even Blackstone reached back to quickening.

If naturalization does not create personhood, how does birth do so, in a clause which puts birth and naturalization in the United States on the same footing?

The purpose of that statement is to describe when someone becomes a citizen. I wouldn't even say, upon further thought, that it has anything to do with deciding when a person comes into being.

Could you be more specific about what Blackstone had to say about quickening? For instance, would a miscarriage after quickening still have produced a legal person?

From Blackstone (with original typography):

"1. LIFE is the immediate gift of God, a right inherent by nature in every individual ; and it begins in contemplation of law as foon as an infant is able to ftir in the mother's womb. For if a woman is quick with child, and by a potion, or otherwife, killeth it in her womb ; or if any one beat her, whereby the child dieth in her body, and fhe is delivered of a dead child ; this, though not murder, was by the antient law homicide or manflaughter o. But at prefent it is not looked upon in quite fo atrocious a light, though it remains a very heinous mifdemefnor.

"AN infant in ventre ftatute mere, or in the mother's womb, is fuppofed in law to be born for many purpofes. It is capable of having a legacy, or a furrender of a copyhold eftate made to it. It may have a guardian affigned to it; and it is enabled to have an eftate limited to it's ufe, and to take afterwards by fuch limitation, as if it were then actually born r. And in this point the civil law agrees with ours."

"The point is, under current law due process does not imply a duty to protect. State governments aren't required to prevent private actors from depriving people of their lives without due process."

But that is not really the issue. The issue is whether the State can, de jure, single out a discrete group and remove it from legal protection.

Suppose a state passed a law that henceforth homicide of blacks is not homicide. Meaning, private parties are free to kill them at will, and face no charge of murder or manslaughter. Let's be stark: under this regime, killing them is akin to killing a rat or stray dog. (This more or less captures the current state of abortion law.)

Does that square with the 14th Amendment's Equal Protection guarantee? I don't think DeShaney answers that question.

It is unconstitutional because racial discrimination is subject to strict scrutiny.

Born-unborn is subject to, at best, rational basis, and there is a rational basis (the interests of the woman) to permit abortion.

That's why you need to move to the DPC, and once you are there, it has to be a positive duty protect.

I doubt the state would win if it chose not to punish the murderers of drug dealers, even though the state would argue deterrence is a rational basis for the policy. I think the better argument is that while a positive duty to protect life is not a fundamental Due Process right, it is a fundamental Equal Protection right, and thus strict scrutiny applies.

1. Under Wayte v. United States, you can basically never challenge selective prosecution under the Equal Protection Clause. So I would say that if a state decided not to prosecute certain classes of murders, there would be no justiciable remedy for it.

Remember, the Constitution permits a lot of bad actions. It doesn't bar the states from doing awful things. And selectively prosecuting in very bad ways is one of the things it permits.

2. Like Boerne and DeShaney, Wayte is not a precedent that conservative jurists and legal thinkers would ever want to overturn.

Bear in mind, I have actually talked to some of these people. The reasons I am giving are exactly why federalist society types aren't publishing articles calling for this interpretation of the 14th Amendment. They have thought through the consequences and know it would be terrible writ large for conservative legal philosophy.

The people advocating this are all non-experts on the Internet who have not thought through the consequences at all.

I don't see how you concluded that Wayte established the principle you can never challenge selective prosecution. Quoting from the decision:

Josh, nobody ever wins a selective prosecution case under the Wayte standard, because all the government has to show is some articulable reason why the prosecution strategy was chosen-- even when a fundamental right is at issue (in Wayte, the issue was opposition to the draft, a fundamental First Amendment right).

Dilan, I did not see in Wyate a standard that says all the government has to do is articulate some reason why the prosecution strategy was chosen. Can you quote from the opinion why you think such a standard was established?

"What's an 'opinioon'?"

It's a typo. Now stop being a dick.

On the Internet?

Even if the litigants raised federalism concerns, I wonder if Thomas would vote to strike down the Congressional statute on that grounds if there aren't five votes to overrule Raich. As Ilya argued, the four liberals are likely to vote to strike down the statute only on the basis of individual rights, and I doubt that Thomas could convince all four of the other conservatives to join him in overruling Raich.

Another possibility is that the conservative majority upholds the statute as a permissible exercise of Congress's enforcement of the Fourteenth Amendment's guarantee of life, overruling or greatly limiting City of Boerne.

This sort of thing is why the greatest SCOTUS justices are not the ones with the flowery rhetoric like Scalia and Robert Jackson, but the ones who can count to 5.

Someone like a William Brennan might be able to craft an opinion that pulls in Thomas' vote (assuming he was willing to vote to strike down an abortion statute on commerce clause grounds).

Hats off to Brennan if he could craft an argument that would strike down the statute on Commerce Clause grounds without overruling Raich.

Thomas has never been shy on splitting decisions. Thomas has been one of the most consistent justices on the limitations of the Commerce Clause. It would only hurt his cause if he decided that he would ignore CC limitations in this case just because he wasn't sure he would be able to get a majority next time it came up.

As far as overruling Raich, Raich was a 6-3 decision with the 3 conservatives in dissent. Of the 2 conservatives in the majority, Kennedy didn't decide federalism was important till later in his career, and Scalia thought drugs were more important than federalism. But given the makeup, it does suggest that conservatives are more likely to go along with a federalist overruling of the decision next time. Gorsuch should be a sure thing, and Kavanaugh seems likely to be as well. Both Roberts and Alito have spent a lot of words on federalism and the Commerce Clause but it remains to be seen if their preference for federalism has a "but drugs" qualifier like Scalia did.

(Scalia was especially disappointing on not just Raich, but also Employment Division, where he was willing to completely jettison Free Exercise rights because of the importance of the "but drugs" hidden clause.))

I'm with Orin Kerr on the significance of Raich, and suspect Roberts would concur as his votes in Comstock and NFIB suggest.

Agree on first point. But as to second point, assuming that unborn babies have a legal right to life (which Scalia specifically denied), this wouldn't implicate Boerne. Boerne concerned a case where Congress prohibited states to do something which they were Constitutionally permitted to do (treat churches the same as other entities). Here, states would be prohibited by the fourteenth amendment to permit abortion. This wold run afoul of the Civil Rights Cases, though, since this bill is prohibiting private, as opposed to state, denial of life.

I am assuming the Court agrees with Scalia and holds that the states have the option of permitting or prohibiting abortion.

The mechanics of the way it would work, is that Congress couldn't directly outlaw abortion, or demand that states outlaw it. What they could arguably do is, present states with the option of either legalizing murder entirely, or enforcing state laws prohibiting murder against abortionists. "Equal protection of the law" would be the basis, and Congress would declare that the unborn were part of the People entitled to that protection.

And Congress doesn't get to do that under Boerne, which no conservative justice is ever going to want to overturn.

I think it is highly likely Thomas would say that abortion doesn't constitute interstate commerce.

There are plenty of places where this comes up. For example, in Allied-Bruce, Thomas and Scalia dissented saying the Federal Arbitration Act doesn't apply in state court under Erie Doctrine because arbitration is procedural and therefore federal civil procedure only applies in federal court. If it were all about tactical voting, the "liberal" block of the court which is opposed to a broad reading of the FAA would side with Thomas and substantially limit the impact of the FAA.

I note that this blog post is accompanied by multiple hysterical political banner ads from Planned Parenthood. Funny. Your tax dollars at work!

Anyway, Justice Thomas is among the greatest justices of all time.

Why is it, "your tax dollars"?

Does the Reason Foundation receive taxpayer funding? (Beyond, perhaps a 501(c)4 exemption)

Planned Parenthood's largest source of revenue is taxpayer funds. Over $1.5 billion from 2013-2015.

For provision of lawful and beneficial services, you authoritarian right-wing rube.

Do you object to Chick-fil-A being a pet vendor to retrograde bigots with government credit cards?

Over $500 million/year and going up drastically in recent years, despite the number of patients going down. Your tax dollars at work!

Planned Parenthood delivers us from Malthusian disaster the way the tax-funded Center for Disease Control in Atlanta delivers us from epidemics and germ warfare terrorism at the hands of religious fanatics. Until the superstitious enter the dustbin of history, taxing the church is a better move than cutting off PP or the CDC.

Ah, yes -- surely, the sacrifice of around 1 million American babies per year is necessary to appease the gods--er, I mean, to continued prosperity.

Interesting how this fervent, evil, irrational belief in child sacrifice permeates millennia of human history, both in the Americas and elsewhere. The more things change, the more they stay the same. Who are the superstitious fanatics, again?

Oh -- but also, let's not forget, importing 1.5 million mostly 3rd world foreigners per year is ALSO necessary to maintain prosperity and necessary population growth. Right?

The reality is, abortion would probably continue apace without shoveling billions down the sinkhole of Planned Parenthood's lobbying, activism, enriched executives, and mass funneling of cash for Democrat fundraising. Let's not pretend that people paying their own $300/pop is a big impediment, especially with all the good hearted liberal donors shelling out enough cash to abort every baby in the country.

"The reality is, abortion would probably continue apace without shoveling billions down the sinkhole of Planned Parenthood's lobbying, activism. . . ."

You're right!

Abortions would continue apace even if Planned Parenthood didn't exist because Planned Parenthood DOES NOT PERFORM ABORTIONS.

LOL @ your loud, incredible ignorance.

"Planned Parenthood self-reports that 323,999 abortions were performed at its facilities nationwide for the year ending September 30, 2015.

That represents 35 percent of the 926,200 U.S. abortions estimated for calendar year 2014, the latest year studied by the Guttmacher Institute, a research and advocacy organization whose survey-based data on abortions is widely quoted by both sides in the abortion debate.

Grothman maintains 49 percent of abortions are performed by Planned Parenthood. That's because he uses the smaller base of 664,000 abortions -- the figure reported by the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. That number is based on voluntary reporting. . .

Grothman told constituents that "Planned Parenthood is the biggest abortion provider in the country."

The agency's national network of clinics stands apart from other providers as the undisputed leader when it comes to providing abortion services.

This is one of those truisms that is basically, well, True."

Source: Left-Wing Politifact

I've always thought that the main problem with Roe v. Wade is not that it struck down the state statute but that it essentially established arbitrary conditions, rather that as the Court has done in many cases strike down laws on narrow grounds then allow the Legislatures or Congress to work to find a consensus. That is how the evolving death penalty jurisprudence has operated and how the school integration cases operated. That created a very sharp divide in the country and effectively prevented either side from talking to the other.

From that perspective the problem was less Roe v Wade than Doe v Bolton.

Roe v Wade permitted states to significantly regulate abortion after the first trimester, except in cases of medical necessity. What Doe v Bolton did, was render a doctor's decision that an abortion was 'medically necessary' unreviewable. Doctors were free to pretextually declare abortions medically necessary. For instance, a doctor could declare that a patient's desire to have the abortion was sufficient that denying it would cause mental anguish, and on that basis was "medically necessary".

Thus, on the same day that the Court ruled states could regulate abortion, they carved out an exception that totally swallowed the rule.

Interestingly, Doe v Bolton was litigated without notifying 'Doe', who tried to get it overturned on the basis that she hadn't consented to the case, and wouldn't have consented if asked. At every level the courts refused to permit this argument. She was really just fake plaintiff for the ruling that they'd wanted, her actual opinion was of no interest to the judiciary.

"essentially established arbitrary conditions"

It drew doctrinal lines based on weighing various state interests and constitutional interests at stake.

Debate can be made about how they did it but not sure what is so "arbitrary" about it as compared to any number of other doctrinal lines. I would have let things develop more slowly but the net result over a span of years would probably be something similar.

I am concerned about something that I can't recall coming up except in this discussion. That is, if the Federal Government can charge someone for a crime committed overseas that is legal where the act occurred, can a State charge a citizen of the State for an act that is illegal in his state, but legal in another, when the act occurred in the other state? (Sorry for the fractured syntax.)

If abortion was outlawed in Arkansas and an Arkansas resident went to Missouri for an abortion, could they be charged with breaking the law in Arkansas, as a citizen of Arkansas?

That is, if the Federal Government can charge someone for a crime committed overseas that is legal where the act occurred...

If you're talking about the Mueller indictments, then, yes, the judge should have told Mueller to go pound sand. Apparently the jurisdictional hook was the pretense that since the servers and people who were "victimized" were on American soil, that a US court and law could claim jurisdiction over them.

Of course, if they had been American citizens, US courts and law do have jurisdiction over them, a fact that has, for example, made banking much more precarious and difficult for American expatriates abroad since 9/11. But I don't recall that such universal claims have ever been accepted in the interstate context, unless there was specific federal legislation enabling it. Has there been?

Apparently the jurisdictional hook was the pretense that since the servers and people who were "victimized" were on American soil, that a US court and law could claim jurisdiction over them.

You must be joking. Someone overseas intentionally directs harmful acts to the United States, and you think federal law cannot punish that?

Osama bin Laden and his henchmen plot in a cave in Afghanistan to commit terrorism on US soil, and we are powerless to punish him? (I mean legally, not send the Navy SEALS to kill him.)

Someone in Russia plots to hack into U.S. servers and steal data. Federal law does not reach that? Absurd.

Yeah, US law does not reach non-Americans outside America. That's pretty standard. Yes, we can enact laws that purport to govern the activities of non-Americans outside America, but we lack any real power to enforce such laws. Which is why, for instance, Nigerian scammers are a problem.

This is generally worked around by international compacts, where country B agrees to subject its own citizens to country A's law enforcement under specified circumstances.

Those specified circumstances never include actions which were directed to be done by country B...

Where are you getting this from? It is pretty standard law that intentional acts directed outside the US are subject to US law, just as intentional acts in one state directed to another are subject to the second state's law.

Calder v. Jones is the classic example of this in state to state intentional torts. I believe that has been applied in the international realm by later cases, many involving terrorism.

Enforcement is certainly an issue, but US civil judgments are recognized in many places, and we can extradite people on criminal charges. In extreme cases, they could be captured and brought here for trial. Had Osama bin Laden been captured and brought to the US for trial, is there any doubt he would have been subject to trial here?

This bill fails Raich. Wasn't the statute upheld because there was a national regulation of drugs, including in interstate commerce, and permitting intrastate use would affect it? Here, there is no interstate regulation of the abortion trade which would be affected by intrastate abortions. If this bill became law, it would go down at least 8 to 1.

Presumably, the language would mirror the federal partial-birth abortion ban which has the commerce-clause predicate:

"Any physician who, in or affecting interstate or foreign commerce, knowingly performs a partial-birth abortion and thereby kills a human fetus shall be fined under this title or imprisoned not more than 2 years, or both."

Having thought a bit more about the issue, Ohio's Farmer's observation that the law at issue in Raich was upheld because it affected an interstate market Congress wanted to extinguish is relevant, although I disagree that the abortion ban is precluded by Raich. Instead, the commerce-clause jurisdictional predicate in the abortion law presents a different issue than the one in Raich, and is instead controlled by Scarborough.

On the other hand, the last time the Court had an opportunity to revisit Scarborough, it chose not to with only Thomas and Scalia dissenting from the denial of cert.

Mystical bigotry eager to make chattel of women, at the point of guns wielded by someone else. At least Robert Dear had the guts to murder people himself before getting room and board "pro life" at our expense.

Your libertarianism is trumped when the authoritarians are on A Mission From God.

That would make it a good time to toss Raich into the dustbin of history, where it belongs.

How about a ban on

-selling aborted baby parts in interstate commerce

-buying abortion-related equipment in interstate commerce

-transporting any person in interstate commerce for the purpose of abortion

How about a ban on

.....

-transporting any person in interstate commerce for the purpose of abortion

How would that work? Are you proposing to punish Delta Airlines or Greyhound for selling a ticket to a woman seeking an abortion? If not, on what basis do you propose punishing an individual who gives a woman a ride across a state line?

Is it even remotely Constitutional?

I said "for the purpose of abortion," suggesting intent.

It would probably work similarly to several other similar federal laws, for example,

https://www.law.cornell.edu/uscode/text/18/2421

The Republican Mann Act was spun off the Comstock laws that banned condoms, diaphragms and birth control booklets with as much as a ten-year prison term. The LP platform plank of 1972 became the Roe v. Wade decision once argued by Austin attorney Libby Linebarger after the vote count.

Readers, observe the courage of masked superstitious bigots eager to fabricate unrealities as pretext for sending men with guns to bully pregnant women and strip them of individual rights. Eddy is The Republican Party sockpuppeted.

Howdy!

In fact, I don't propose to strip anyone of any rights - unless we beg the question and assume killing your children is an individual right.

By the way, what sex are at least half (and probably more) of the unborn children killed by abortion? Hint: Female.

And I don't particularly care which party gets to claim the credit of protecting the right to life of all innocent living human beings, so long as someone does it. Democrats could do it if they wanted.

"...the right to life of all innocent living human beings..."

As I point out below, the law considers a new, "innocent", living human being to come into existence at one particular point in human development. I'll give you a hint about when that is: You have a certificate declaring your newfound legal existence with that point as part of its name.

If you want to declare an embryo or fetus to be a person with its own legal rights equal to yours as you are now, then you are changing law that has existed since time out of mind. What is your argument for changing this?

As I said, even Blackstone went back to quickening - what do you mean by time out of mind?

Time out of mind is a phrase I recalled as indicating something stretching back as far in history as anyone could think of.

If you want to declare an embryo or fetus to be a person with its own legal rights equal to yours as you are now, then you are changing law that has existed since time out of mind. What is your argument for changing this?

Maybe the unborn did not have rights equal to those it will have after birth but they have enjoyed substantial protection in this country since right after the founding.

Abortion remained a felony in 49 of 50 states until 1967. The pro-life argument is simply to restore what, until the 1960s, was the traditional protections afforded the unborn.

Also keep in mind that the Hippocratic Oath, sworn to by physicians since the time of the Greek physician Hippocrates (c.460-377 BC) includes: "Similarly I will not give to a woman an abortive remedy." So the proscription against abortion didn't just begin in the 19th century. (Modern physicians have dropped this part of the oath.)

How do you explain all the homicide laws that are triggered if somebody kills a fetus (outside of an abortion)?

How do you explain all the homicide laws that are triggered if somebody kills a fetus (outside of an abortion)?

I am far more skeptical of Roe v. Wade than Professor Somin is, and I also agree Raich v. Ashcroft significantly overextended Wickard v. Filburn.

But I strongly doubt that every one of the 4 post-Raich Conservative Justices would join Justice Thomas in voting to overturn Raich. And if they don't, I fear a regime in which "interstate commerce" magically doesn't include anything the Court's liberals don't personally like but magically includes everything they do like would make an even greater mockery of the written constitution than exists at present.

Without overturning Raich, perhaps abortion itself could be distinguished from possession of a commodity etc. But all Congress would have to do would be to prohibit abortion using an object (scalpel, pill, etc.) that had previously been part of interstate commerce and, if current gun legislation jurisprudence is any indication, it could accomplish pretty much the same thing.

Even if Raich were overturned, older conceptions of interstate commerce would enable Congress to have an impact on the issue. Congress would, for example, be able to prohibit crossing state lines for purposes of an abortion, among other things, and remain consistent with concepts of the scope of interstate commerce that precede even Wickard v. Filburn.

Both Wickard and Raich were terrible decisions. Throw them both out.

I support making abortion illegal for women with IQs above 115, and mandatory for women with IQs below 95. Those with IQs between 95 and 115 should be allowed to choose.

But then you would have never been born.

Turning abortion back to the states is a major reversal of the current situation.

But if SCOTUS concludes that fetuses fall under the protection of the US Constitution or that abortion on demand violates the rights of fathers, there may well be federal restrictions as well.

Either way, Roe v. Wade is likely going to fall one way or another.

A father only has parental rights regarding his child. Until a child comes into existence (in the legal sense), there is no father to have rights. If you consider a fetus to be a child, such that its father would have rights, then the situation is moot as you've already given it sufficient legal status to justify blanket prohibitions on abortion.

I don't think that SCOTUS is going to try and rule on when a new human life begins for legal purposes. I can't think of a time when that point has been other than when a baby is born alive. It would truly be making new law for SCOTUS to rule otherwise.

Perhaps, but the invalidation of Roe v. Wade -- or even eviscerating it with big-government restrictions on abortion -- seems likely to be the straw that enlarges the Court.

There just aren't enough yahoos to support or permit criminalization of abortion in America for long, and the yahoo population diminishes daily as America improves.

America's abortion absolutists, like the gun nuts, appear have tied their political prospects to the wrong electoral coalition.

There just aren't enough yahoos to support or permit criminalization of abortion in America for long, and the yahoo population diminishes daily as America improves.

If that's true, then it sounds like Roe v. Wade could be invalidated without much actual effect on the abortion laws in this country.

Any criminalization of abortion is favored only by Yahoos?

Has it occurred to you that many of us, solidly backed by science, believe that fetuses at some age are human persons, deserving of rights, the most important of which is the protection against the taking of their life except in extraordinary circumstances?

Or does that make us Yahoo's?

In physics, generally implies a generalization to all cases. See Feynmann lectures

Clarence Thomas is to constitutional theory as Jackson Pollock is to painting. Whatever you are seeing is emanating from you, not from the page or the canvas.

" From an originalist point of view, the idea that the Commerce Clause gives Congress virtually unlimited authority to ban the possession of any product of any kind is highly implausible"

We don't apply the law from "an originalist point of view," full stop, and the opinion does not give Congress "virtually unlimited authority" anyway. There are a range of limits in place. Just not enough for you.

The DOMA case was a prime time for Justice Thomas to show his federalist bona fides and people like Prof. Adler led the way there -- marriage is a state institution generally and that law arbitrarily interfered with state power in that area. Thomas also could have asked the Court (as he seemed to do in McDonald v. Chicago since he was the only one who cared about the privileges or immunity argument; Scalia ridiculed it) to add a question to the national abortion ban case they did take. The Supreme Court does that repeatedly.

At times, like Raich, Thomas' views might have liberal/libertarian results but I wouldn't trust it too much for liberal social interests generally.

This whole post seems misplaced to meet. The vast majority of abortion cases relate to state attempts to regulate (or ban) abortion, not federal attempts. Whatever you think about the Commerce Clause, the states certainly have the power to regulate something like abortion, if it ever came to pass that Roe v. Wade was overturned.

This whole post seems misplaced to meet. The vast majority of abortion cases relate to state attempts to regulate (or ban) abortion, not federal attempts.

Yet there is no shortage of federal attempts to regulate abortion.

the states certainly have the power to regulate something like abortion

Why is it impossible that a fetus could be judged to be a person entitled to constitutional rights? Some of the rationale in Obergefell could be used:

The first principal at work here is that the right not to be aborted is inherent in the concept of individual autonomy. The second is that the right is fundamental because it supports a parent-child union unlike any other in its importance to the committed individuals. The third principle is that it safeguards children and families and thus draws meaning from related rights of childrearing, procreation, and education. Finally, this Court's cases and the Nation's traditions make clear that the right is a keystone of the Nation's social order.

The right of the fetus to not be aborted is also derived from the Fourteenth Amendment's guarantee of equal protection. The Due Process Clause and the Equal Protection Clause are connected in a profound way. The right is also a fundamental right inherent in the liberty of the person.

While the Constitution contemplates that democracy is the appropriate process for change, fetuses who are harmed need not await legislative action before asserting a fundamental right. The fundamental liberties protected by the Fourteenth Amendment's Due Process Clause extend to fetal dignity and autonomy. They ask for equal dignity in the eyes of the law. The Constitution grants them that right.

"The first principal at work here is that the right not to be aborted is inherent in the concept of individual autonomy."

This totally begs the question. There can't be a right "not to be aborted" until there is a person with rights. None of what you said here answers the question of exactly when should we assign the rights of personhood.

No, it doesn't precisely answer it. But it rests on a strong case that at some point we should attribute personhood to a fetus, from which the rights inherently follow.

This totally begs the question. There can't be a right "not to be aborted" until there is a person with rights.

No more than it begs the question to assert that the right to same-sex marriage is inherent in the concept of individual autonomy (without explaining why the same couldn't be said about bigamy or adult incest or prostitution or any number of other activities prohibited for moral reasons).

To me it seems a bit of a stretch to argue that any repudiation of abuses of the Commerce Clause or a rolling back to 18th century foundations must require the federal government to abdicate its one true and legitimate purpose and responsibility, to equally protect the rights, liberties, and freedoms of all the People, especially the first and clearly the most important and precious among them, the right to life. One only need read the enumerated list of inalienable natural rights spelled out, in order of importance, by Thomas Jefferson, in the second sentence of the Declaration Of Independence, the nation's very founding document, signed by the new nation's founders, to understand their intent to prioritize the right to life before that of liberty and happiness, knowing full well that without life there can be no liberty and no happiness.

Remember Marshall said of the Commerce Clause that the power to regulate "with foreign nations" is "identical" as the power "among the several states."