The Volokh Conspiracy

Mostly law professors | Sometimes contrarian | Often libertarian | Always independent

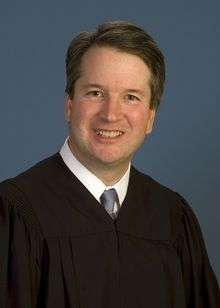

Kavanaugh on the Nixon Tapes Case

In 1999, Judge Kavanaugh suggested that the Supreme Court case that forced Nixon to turn over the Watergate tapes may have been wrongly decided. But it's not entirely clear what he now thinks about the issue.

In a 1999 roundtable discussion, Judge Brett Kavanaugh, President Trump's nominee for the Supreme Court, suggested that United States v. Nixon, the 1974 Supreme Court decision that forced Richard Nixon to turn over the Watergate tapes to prosecutors, may have been wrongly decided. This AP report summarizes what he said:

A 1999 magazine article about the roundtable was part of thousands of pages of documents that Kavanaugh has provided to the Senate Judiciary Committee as part of the confirmation process. The committee released the documents on Saturday….

"But maybe Nixon was wrongly decided — heresy though it is to say so. Nixon took away the power of the president to control information in the executive branch by holding that the courts had power and jurisdiction to order the president to disclose information in response to a subpoena sought by a subordinate executive branch official. That was a huge step with implications to this day that most people do not appreciate sufficiently… Maybe the tension of the time led to an erroneous decision," Kavanaugh said in a transcript of the discussion that was published in the January-February 1999 issue of the Washington Lawyer.

At another point in the discussion, Kavanaugh said the court might have been wise to stay out of the tapes dispute. "Should U.S. v. Nixon be overruled on the ground that the case was a nonjusticiable intrabranch dispute? Maybe so," he said.

It is not clear, however, that Kavanaugh actually believes Nixon was wrong. As the AP story also notes, he has praised the decision more recently, in a 2016 article in the Catholic University Law Review:

As a judge, you must, when appropriate, stand up to the political branches and say some action is unconstitutional or otherwise unlawful. Whether it was Marbury, or Youngstown, or Brown, or Nixon, some of the greatest moments in American judicial history have been when judges stood up to the other branches, were not cowed, and enforced the law. That takes backbone, or what some call judicial engagement. To be a good judge and a good umpire, you have to possess strong backbone.

In theory, Kavanaugh could believe that Nixon was both "an erroneous decision" and also one of "the greatest moments in American judicial history." But these two descriptions of the case are not easily reconciled. Another possibility is that, in the 1999 discussion, he was merely outlining a view that he himself did not necessarily agree with. He did say "maybe Nixon was wrongly decided" (emphasis added), not that it definitely was. Perhaps the "maybe" here is more important than it might initially seem. Finally, it's possible that Kavanaugh believed that Nixon was wrongly decided back in 1999, but had changed his mind about the subject by 2016. Based on the currently available evidence, it is not easy to figure out what Kavanaugh actually thinks about Nixon.

If the president could reject subpoenas for executive branch documents requested by prosecutors, and courts have no authority to enforce them, that would give him broad power to shield executive wrongdoing from investigation. That includes not just the president's own potentially illegal actions, but also those of subordinate officials. The issue goes far beyond the currently ongoing Mueller investigation into the Trump campaign's possible collusion with Russia, and could affect future investigations of other types of potentially illegal activities by the president and his subordinates.

Thus, if Kavanaugh really believes that Nixon was wrongly decided, that would be a troubling development, and a strike against him. It would, at the very least, reinforce concerns that he has an overly broad view of executive power.

Admittedly, Kavanaugh is far from the only serious legal commentator to have raised questions about Nixon. Many have suggested that it seems paradoxical that the president must disclose evidence at the request of a prosecutor who was, after all, one of his own subordinates. If Nixon had the power to fire special prosecutor Leon Jaworski (as he famously did with his predecessor Archibald Cox during the "Saturday Night Massacre") or order him to terminate his investigation, why didn't he have the seemingly lesser power to refuse to turn over particular documents or tapes?

The answer, I think, is that the power to fire a prosecutor or terminate an investigation does not imply immunity against federal laws governing subpoenas and the disclosure of relevant evidence to the courts. While the president can fire federal prosecutors or shut down a particular investigation, so long as he does not do so he and his subordinates are still subject to the same laws governing evidence as everyone else, subject to specific statutory exceptions for disclosure of national security secrets and the like. Nothing in the text of the Constitution exempts the president from obeying those laws (though of course Congress could create exceptions by statute).

Nor is this just a purely formalistic distinction. In at least some cases, it matters a great deal in practice. While Nixon could have fired Jaworski, he would have paid a high political price for doing so (especially after he had already taken a political beating for firing Cox). Resisting the release of specific pieces of evidence seemed like a less politically risky strategy, which is probably why Nixon chose to pursue it instead of axing Jaworski. Similarly, today, Trump so far has not tried to fire Mueller or shut down the Russia investigation - most likely because he fears the resulting political backlash. On the other hand, refusing to turn over specific pieces of potentially incriminating evidence might be more likely to fly under the radar screen of the public.

Even if Kavanaugh really does believe that Nixon was wrongly decided and would vote to reverse it if the opportunity arises, it is unlikely he could get four other justices to support that view on the current Court. But it is possible he could, over time, help build a majority for limiting Nixon's scope, perhaps by creating various exceptions to the President's duty to turn over documents in response to subpoenas. Nixon itself already indicates that such exceptions are available "to protect military, diplomatic, or sensitive national security secrets." One can imagine broadening this to include other types of supposedly sensitive information.

Executive power is far from the only question that should be considered in assessing Kavanaugh's nomination. In my view, he is both a highly competent jurist, and has an excellent record on a number of other important issues. As with any nominee, the good should be weighed against the bad. We should also remember that a Supreme Court justice could well serve for many years, and hear cases on a variety of important issues that we may not be able to foresee today. But Kavanaugh's views on both Nixon and executive power generally are well worth investigating, and the Senate should definitely ask about these matters during his confirmation hearings.

Editor's Note: We invite comments and request that they be civil and on-topic. We do not moderate or assume any responsibility for comments, which are owned by the readers who post them. Comments do not represent the views of Reason.com or Reason Foundation. We reserve the right to delete any comment for any reason at any time. Comments may only be edited within 5 minutes of posting. Report abuses.

Please to post comments

Being shielded from an executive branch subpoena is also far different from being shielded from a congressional subpoena. I could well see Nixon having been wrong while for an otherwise identical case featuring congressional action it could be entirely proper.

Right. It is entirely in Congress' power to ensure that a special prosecutor is free from interference by the President, the specific example being the (now defunct) special prosecutor provision in the Ethics in Government Act, following Watergate.

That depends on which branch the special prosecutor works for.

Exactly. Supporting Nixon is just supporting Congressional abdication. It is their job to investigate the executive, and if they are stonewalled, it is their job to impeach/remove officials until there is one who complies.

the power to fire a prosecutor or terminate an investigation does not imply immunity against federal laws governing subpoenas and the disclosure of relevant evidence to the courts. While the president can fire federal prosecutors or shut down a particular investigation, so long as he does not do so he and his subordinates are still subject to the same laws governing evidence as everyone else, subject to specific statutory exceptions... Nothing in the text of the Constitution exempts the president from obeying those laws

I don't see the distinction. If the President can fire the prosecutor, he can name a replacement. It shouldn't be too hard to find someone who would drop the case.

While Nixon could have fired Jaworski, he would have paid a high political price for doing so (especially after he had already taken a political beating for firing Cox). Resisting the release of specific pieces of evidence seemed like a less politically risky strategy, which is probably why Nixon chose to pursue it instead of axing Jaworski.

The only political price Nixon, already in his second term, would have feared was impeachment. Surely he knew that release of the tapes would be at least as explosive as firing Jaworski, so he had to avoid their release. I suspect that he thought the court would rule his way. That turned out to be wrong, but my guess - just that - is that he was looking for the best strategy to avoid disclosure, not to minimize political damage more broadly.

There was no way to avoid a release.

What would have stopped the House from petitioning gor a subpoena.

Partisan politics. The incentive is for the President's party to slow walk the proceedings as much as possible to mitigate any damage by association.

That is not the incentive of prosecutors.

Who controlled the House in 1974?

Do you think the minority had no power to slow things down in 1974?

As I was trying to say above, regardless of party the incentives are better aligned if you are not a political/partisan branch.

So to whom should a prosecutor answer to

Not in the House of Representatives, no. The minority had zero power to avoid any action that the Democratic majority was prepared to take, up to and including passing articles of impeachment.

"Partisan politics. The incentive is for the President's party to slow walk the proceedings as much as possible to mitigate any damage by association."

Except if you're running interference for your guy, he's, well, going to be seen as "your guy". Better to stay out of the way, and keep your seat(s).

Depends on how effective you think the interference will be. If Nixon doesn't go down until your next guy's in office...

Indeed, most Republicans in the House were not at all inclined to take the impeachment route until the revelation of Nixon's active participation in the activities in question. They likely would have accepted Nixon's offer to release redacted transcripts (he thought Cox, and then Jaworski, would do that).

What would have stopped the House from petitioning gor a subpoena.

Well, I don't know for sure, but presumably Nixon would have challenged that as well, so it would still depend on the Supreme Court.

"I don't see the distinction. If the President can fire the prosecutor, he can name a replacement. It shouldn't be too hard to find someone who would drop the case."

But then he would have had to fire the prosecutor, and either declare that there would be no successor or name a replacement (toady).

These are things which are visible, both to the public and to the House of Representatives.

Doing this is damaging to one's own effective leadership, as well as to one's party's electoral futures.

People who talk about executive power often do so forgetting that executive power is borrowed from the people.

Trump could end all the "witch hunt!" today, by ordering the Department of Justice to drop it and firing anyone who didn't fall in line.

If he did that, his party might decide to hold real hearings and not "but Hillary..." whinefests, or they might choose to ignore it.

If the party chooses to ignore it, they might not be the party in charge of the Congress next time.

It's a question of short-term power vs. long-term power..

The distinction I disagree with is the one between being able to fire the prosecutor and being immune from subpoenas. Both allow the President to dodge the investigation.

It may be that firing is worse politically, but how much does that matter to an embattled President? Nixon, unlike Trump, couldn't run again, and I'm doubtful that a President facing possible impeachment attaches much priority to the fate of his party in upcoming elections, or can really do much regardless.

"It may be that firing is worse politically, but how much does that matter to an embattled President?"

Quite a bit, I think. Nixon resigned because even his up-til-then supporters decided he needed to go. Anything that nudged them away from supporting him mattered quite a bit.

"The distinction I disagree with is the one between being able to fire the prosecutor and being immune from subpoenas. Both allow the President to dodge the investigation."

If you fire the prosecutor, that's a power the President definitely has, but this act is visible to the public and to the House. If the prosecutor has subpeona's documents, then those documents get delivered to the new prosecutor. The new prosecutor may stonewall the case, having read the handwriting on the wall, but the House of Representatives will have seen the firing and appointment (and the Senate gets to weigh in on THAT) so Congress can act to counterbalance a crooked chief executive.

If it's functional, as the present Congress, alas, is not.

I would think that speaks pretty well for him considering he had just finished up working on the Lewinsky investigation. Not very often you hear a prosecutor question their tools of investigation.

The "Lewinsky investigation", of course, was about something totally different when it started, as it would have to be seeing as how the investigation started two years before there was anything about Ms. Lewinsky to investigate.

That particular "investigation" was questioned by close to everyone, from the side that got hammered by it to the side that fully expected to get hammered by the next one, because what goes around, comes around.

Congressional committees can also issue subpoenas, but separation of powers principles make judicial enforcement of a committee subpoena directed to the president extremely unlikely. See Senate Select Committee on Presidential Campaign Activities v. Nixon,498 F.2d 725 (D.C. 1974), refusing to enforce a congressional subpoena for specified Watergate tapes. Of course the House could impeach a president who defies a congressional subpoena, and the Senate could remove him from office, but don't expect the courts to enforce a congressional subpoena even if the democrats take control of the House. And don't expect the Sergeant at Arms to take the president into custody for defying a subpoena either.

You're saying he could pull an Andrew Jackson on them -- and you may be right.

He could do the same with judicial subpoenas.

Hard cases make bad law, as O.W. Holmes (and others) said. As a matter of principle, it's hard to dispute that the head of the Executive Branch has the Constitutional authority to overrule the actions of one of his subordinates. On the other hand, if the subpoena is issued by a judge, a member of another Branch independent of the President, it's hard to dispute that the President is as much bound by that court order as any other citizen would be. In Nixon's case, in the end he seemed to think that it would be more harmful to his position to ignore the subpoena than to comply with it.

None of this is relevant to Kavanaugh's nomination to the Supreme Court. But the Democrats are desperate to come up with something, anything, to block a qualified nomination by the duly elected President. You remember how hard they tried to block Thomas, and many of them still treat him as illegitimate.

The case was about whether or not a subordinate, in his official capacity, has standing to subpoena the President. Without standing, a court would lack jurisdiction to issue a subpoena.

This standing problem would have been far less problematic had the House petitioned for a subpoena. The House certainly had standing.

Judges don't issue subpoenas, lawyers do.

There is no judicial action unless the party who receives the subpoena files to quash or the lawyer issuing it seeks a contempt citation or motion to compel.

"You remember how hard they tried to block Thomas, and many of them still treat him as illegitimate."

I also remember how hard they tried to block Gorsuch -- though I'll cut them some slack, given how sleazy McConnell's (brilliant) strategy was.

The Founders knew how to carve out special protections for government officials.

Eg, this provision on Congress, in Art. I, Sec. 6:

"The Senators and Representatives...shall in all Cases, except Treason, Felony and Breach of the Peace, be privileged from Arrest during their Attendance at the Session of their respective Houses and in going to and returning from the same; and for any Speech or Debate in either House, they shall not be questioned in any other Place."

I would most humbly suggest that the Founders are here creating an exception to a general rule, the general rule being that government officials are subject to the law. The President and the judges don't have similar exemptions.

That's my reasoning. Presidents have no formal immunity.

They have a form of practical immunity, because everybody who might prosecute them at the federal level works for them. The answer to that is, of course, impeachment.

In the Nixon case, the prosecutor was not using his own inherent power as prosecutor to issue the subpoena. If that were the case, then it would be strange to say that a subordinate has the authority to subpoena his boss. In reality, the power to issue the subpoena lies with the grand jury, and they are issuing it under the authority of the judicial branch. We only think of it as the prosecutor issuing the subpoena because the grand jury is typically acting as a rubber stamp. Thus, the question is not whether a subordinate can subpoena his boss; rather, it is whether the judiciary can subpoena the executive, a co-equal branch.

The answer to that, I would think, depends on if it has any ability to enforce the subpoena. In the civil context, if the executive refused to comply, the trial court could instruct the jury to make a negative inference based on the non-compliance. In the criminal context, I don't think there is anything they can do. Ordinarily, the court could jail the non-complying witness, but with the President, that would be tantamount to removing him from office, which only the Legislature is empowered to do. So, while Nixon is an ass, I'm leaning towards the case being wrongly decided.