The Volokh Conspiracy

Mostly law professors | Sometimes contrarian | Often libertarian | Always independent

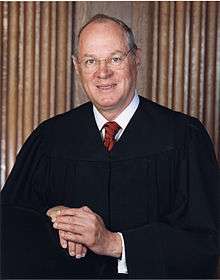

Justice Kennedy Questions Chevron Deference

In a concurring opinion issued today, the Supreme Court's key swing vote justice expressed serious misgivings about a major Supreme Court precedent requiring courts to defer to executive branch administrative agencies.

In a important concurring opinion issued today, Supreme Court Justice Anthony Kennedy expressed serious misgivings about Chevron v. Natural Resources Defense Council, a major Supreme Court precedent requiring federal judges to defer to executive branch agencies' "reasonable" interpretations of federal law in cases where the law is "ambiguous." Kennedy's opinion was a solo concurrence in Pereira v. Sessions:

This separate writing is to note my concern with the way in which the Court's opinion in Chevron U. S. A. Inc. v. Natural Resources Defense Council, Inc., 467 U. S. 837 (1984), has come to be understood and applied….

In according Chevron deference to the [Board of Immigration Appeals'] interpretation [of the statute at issue in this case], some Courts of Appeals engaged in cursory analysis of the questions whether, applying the ordinary tools of statutory construction, Congress' intent could be discerned, 467 U. S., at 843, n. 9, and whether the BIA's interpretation was reasonable, id., at 845. In Urbina v. Holder, for example, the court stated, without any further elaboration, that "we agree with the BIA that the relevantstatutory provision is ambiguous." 745 F. 3d, at 740. It then deemed reasonable the BIA's interpretation of the statute, "for the reasons the BIA gave in that case." Ibid. This analysis suggests an abdication of the Judiciary's proper role in interpreting federal statutes.

The type of reflexive deference exhibited in some of these cases is troubling. And when deference is applied to other questions of statutory interpretation, such as anagency's interpretation of the statutory provisions that concern the scope of its own authority, it is more troubling still….

Given the concerns raised by some Members of this Court, see, e.g., id., at 312–328; Michigan v. EPA, 576 U. S. ___, ___ (2015) (THOMAS, J., concurring); Gutierrez-Brizuela v. Lynch, 834 F. 3d 1142, 1149–1158 (CA10 2016) (Gorsuch, J., concurring), it seems necessary and appropriate to reconsider, in an appropriate case, the premises that underlie Chevron and how courts have implemented that decision. The proper rules for interpreting statutes and determiningagency jurisdiction and substantive agency powers should accord with constitutional separation-of-powers principles and the function and province of the Judiciary.

Kennedy is the Supreme Court's key swing voter on many issues, and his criticism of Chevron deference in today's opinion increase the likelihood that Chevron deference will be overruled or at least narrowed in future Supreme Court decisions. It is also notable that in referring to "the concerns raised by some Members of this Court," Kennedy cites well-known opinions by Justices Clarence Thomas and Neil Gorsuch suggesting that Chevron should be overruled entirely, because it is an abdication of judicial responsibility. For reasons I summarized here, I believe that Gorsuch and Thomas are right about this. The courts should not farm out issues of legal interpretation to executive branch agencies - especially not in an era of extreme polarization when those interpretations are often heavily influenced by partisan and ideological bias. Kennedy is right to imply that agency bias may be especially likely in cases where the agency interprets the scope of its own authority.

Kennedy's opinion does not not necessarily mean he is willing to go as far as Gorsuch and Thomas. It is possible he prefers to narrow the scope of Chevron deference rather than get rid of it completely. Even with Kennedy's support, it is not yet clear that there are five votes on the Supreme Court in favor of significantly paring back Chevron. Nonetheless, the opinion is a signal that Chevron may well be in more serious trouble than many commentators (myself included) previously believed.

It is also worth noting that conservatives like Gorsuch, Thomas, and now Kennedy are not the only ones who have begun to seriously question Chevron. In a recent Harvard Law Review article for which they surveyed forty-two federal appellate judges, Judge Richard Posner and Abbe Gluck found widespread skepticism about Chevron among both liberals and conservatives. In his solo dissent in Pereira, Justice Samuel Alito calls Chevron "an important, frequently invoked, once celebrated, and now increasingly maligned precedent." He isn't wrong to suggest that the ranks of the "maligners" are growing.

UPDATE: I should note that Kennedy's views may not matter much if he retires from the Court this year, as many have speculated he might. My own reading of the tea leaves is that he probably will not retire. But I could easily be wrong about that, and my track record on predicting what Kennedy may or may not do is very far from perfect.

Editor's Note: We invite comments and request that they be civil and on-topic. We do not moderate or assume any responsibility for comments, which are owned by the readers who post them. Comments do not represent the views of Reason.com or Reason Foundation. We reserve the right to delete any comment for any reason at any time. Comments may only be edited within 5 minutes of posting. Report abuses.

Please to post comments

The court should review the key questions without deference... is the statute actually ambiguous (or is the agency attempting to accrue authority not intended by Congress for the agency to have) and second, is the agency interpretation reasonable.

If those two steps are passed, however, the courts should leave the law as they find it rather than making changes just because they can.

Yes, the threat of a highly-polarized executive agency doing something out-of-scope is real. But if they're doing something that isn't blatantly unreasonable, then Congress should alter their legal choices, not the courts.

Count me among Alito's "maligners". Chevron should be flatly overturned. Executive agencies should get no deference at all to their own interpretations of the law.

While that does leave the possibility of a court substituting its judgement for the agency's, Congress is free to overturn the interpretation and to eliminate the ambiguity in either case. During the period while we're waiting for Congress to do so, however, having an independently reviewed decision control seems dramatically less-bad than allowing a self-serving agency decision to stand.

"period while we're waiting for Congress to do so, however, having an independently reviewed decision control seems dramatically less-bad than allowing a self-serving agency decision to stand."

So politicizing the courts is fine, because Congress can fix it?

Hell no. They should stick to overruling unreasonable interpretations only.

"They should stick to overruling unreasonable interpretations only."

I sort of agree, but that only applies if the statute is ambiguous and the courts should give agencies NO deference on the predicate issue of whether or not the statute is ambiguous.

Please scroll up and read the first comment in this thread.

Consider it in an other-than-Chevron scenario. If a criminal prosecutor makes a claim, is it "politicizing the court" to give the prosecutor's ideosyncratic interpretation of the law no deference? Or is that the court's actual job?

Interpreting the law is what courts do. And while that interpretation sometimes has political consequences, I'm not seeing how that immediately escalates to "politicizing the court".

You don't see how wading into a fray between an executive agency and Congress (you know, the political branches of government) leads to politicizing the court?

If the authorizing statute is ambiguous, and the agency's interpretation is reasonable, and a court decides to insert its own judgment, there are many possible results, some overlapping:

1. Different courts might have differing opinions about the most reasonable interpretation, requiring appeals, possibly circuit splits.

2. A well-established interpretation, to which any number of entities have relied, gets discarded, requiring all those entities to reformulate their plans,

3. Possibly the court's guess as to a more reasonable interpretation turns out to be a less reasonable one.

If you're dealing with an unreasonable interpretation, then Chevron deference doesn't apply, and courts can (and should) act at the first opportunity. But if you're dealing with a reasonable one, chalk it up as stare decisis and move on to the next case.

I think you're making hidden assumptions in your analysis. Declining to defer to an Executive Agency does not automatically mean that there is any fray between the Agency and Congress.

But to the extent that there is any disagreement between the Executive and Congress, yeah I do think that the Legislative Branch should get the most say about legislation. If Congress really was ambiguous, courts are no worse than agencies at resolving the ambiguity - and given the independence problems, considerably less-bad.

Will that lead to circuit splits? Yes. Just like we have circuit splits about criminal law interpretations and everything else. That's why we have superior courts and ultimately a Supreme Court to sort out the splits.

Will that result in previously-held interpretations being overturned? Yes. Again, not unusual in any other scenario. And again, a feature, not a bug. Bad decisions should be overturned no matter how many people inappropriately relied on them.

Will the courts sometimes be wrong? Again, yes. No one expects courts to be perfect. But there is no reason at all to suggest that Executive Agency bureaucrats will be any better.

This is not to say that Executive Agencies are always wrong. If there interpretation really is reasonable, there is a high probability that the court will reach the same interpretation. But there is no good reason to blindly defer to the Executive in conducting that analysis.

"I think you're making hidden assumptions in your analysis. Declining to defer to an Executive Agency does not automatically mean that there is any fray between the Agency and Congress."

You don't get to Chevron unless Congress was ambiguous. You don't get a court case unless there's a current case or controversy. So there's definitely a fray involving Congress, the executive branch of the federal government, or both, if you're concerned with Chevron deference.

If the executive branch has something that is both reasonable AND wrong, it's the legislature's job to fix it, not the judiciary's.

"there is no good reason to blindly defer to the Executive in conducting that analysis."

Nor has anyone suggested that anyone should. Find a different strawman.

Start by re-reading the opening comment in this thread.

Your reasoning is flawed. That Congress was purportedly ambiguous does not make Congress a party to the dispute. The fray involves the executive branch and (typically) a private party. Not Congress.

" That Congress was purportedly ambiguous does not make Congress a party to the dispute."

These are the possibilities:

1) Congress is not ambiguous. They intended what they wrote, and they wrote what they intended. If the executive agency is doing something else, it's not what Congress intended. But if the statute isn't ambiguous, you don't get to Chevron... the statute isn't ambiguous, the agency is wrong, and they lose, without ever implicating Chevron.

2) Congress is ambiguous, but the agency does something they didn't intend. This is a problem between Congress and the agency, and Congress can/should be the entity to fix the problem.

3) Congress is ambiguous, but the agency is doing something Congress is OK with. In that case, the agency should win.

No, no, it isn't. It's a problem between the agency and the party against whom the agency is acting. It is the job of the courts to sort that out. Of course, Congress can try to resolve the issue prospectively, but that's a separate issue, and of course it's impossible to eliminate all possible ambiguities anyway. You are advocating an abdication of the judicial role.

Moreover, even if your three "possibilities" formulation were right, it would not comport with Chevron. Chevron analysis does not ask whether the agency is doing what Congress "intended" (whatever that even means). It requires courts to ask whether the agency's interpretation is a reasonable one. (Not the most reasonable one; just a reasonable one.)

No, no, it isn't. It's a problem between the agency and the party against whom the agency is acting"

This hypothetical third party, who doesn't appear in the text you quoted, is a separate issue.

Whether or not their actions violated the regulation can be adjudicated. Hell, under the APA, it MUST be adjudicated by the agency itself before a court case can even be brought.

" Chevron analysis does not ask whether the agency is doing what Congress "intended"

Yeah, it does. If they pick something that doesn't match their legislative grant of authority, their interpretation of the statute is unreasonable, and deference to the agency is not granted. If their interpretation does make sense within the framework of the enabling statute, then it is accorded deference.

Hard not to read the timing of this as a reaction not just generally to Chevron and its misapplications, but more specifically to what I imagine is Kennedy's disagreement to Sessions' arguments for its application in the immigration context in Matter of AB, 27 I&N Dec. 316 (A.G. June 11, 2018).

" what I imagine is Kennedy's disagreement "

The Sessions opinion came out 9 days ago. Supreme Court opinions percolate for a long time, get passed around to the other justices.

While it is of course possible that Tony started and completed his concurrence after June 11, it is highly, highly unlikely.

As you say, Supreme Court opinions percolate. So a particularly egregious action by someone outside the court may tip the published opinion one way rather than a different variation.

It isn't necessary that the opinion not have been started yet until after that action for that action to have affected the final published opinion.

You have no way of knowing if Tony even saw the Sessions opinion.

Its just a big assumption that am unrelated immigration opinion somehow enflamed Tony enough to alter an opinion. Just because you and ILK thought it was "egregious ", does not 1) make it so or 2) prove it had any influence

"You have no way of knowing if Tony even saw the Sessions opinion"

Nor did I claim I did, Bob.

"Its just a big assumption that am unrelated immigration opinion somehow enflamed Tony enough to alter an opinion."

That's true, Bob. You claimed the alternative assumption was the only one likely, Bob, and that's just not true, Bob.

"Just because you and ILK thought it was "egregious ",

Mind pointing out where I or anyone else said anything was egregious, Bob? What's that? Just your imagination? OK, then.

Mind pointing out where I or anyone else said anything was egregious, Bob?

"particularly egregious action by someone outside the court"

I should not quote you. Got it.

Bob... is English not your primary language?

Where'd ya go, Bob? I challenged you to point to where I (or anyone else) said what you imagined I said. So you quoted me not saying what you imagined I said, and did a mic drop.

Should I assume your continued silence indicates that you've reviewed your posting history, realized your mistake, and are now hiding out of shame?

It appears that assumption is correct, since you're busy whining about Justice Kennedy on another article.