The Volokh Conspiracy

Mostly law professors | Sometimes contrarian | Often libertarian | Always independent

Court strikes down exception from sign code that allowed more flags around certain holidays

Generally speaking, the government can't restrict speech based on its content, unless the restriction falls within a long-standing First Amendment exception (such as for true threats or libel or obscenity) or the government is acting in a special capacity (such as employer or educator). In Reed v. Town of Gilbert (2015), the Supreme Court reaffirmed that a restriction that facially discriminates based on the content of speech is content-based, even if it's not motivated by hostility toward particular speech. For instance, sign ordinances that impose different size and duration limits on election campaign signs than other signs are thus presumptively unconstitutional, because they are content-based.

But what if a restriction is facially content-neutral, but is hard to explain except as an attempt to deliberately restrict or prefer speech of a certain content? In Reed, the court held that such restrictions may also be treated as content-based:

Our precedents have also recognized a separate and additional category of laws that, though facially content neutral, will be considered content-based regulations of speech: laws that cannot be "'justified without reference to the content of the regulated speech,'" or that were adopted by the government "because of disagreement with the message [the speech] conveys." Those laws, like those that are content based on their face, must also satisfy strict scrutiny.

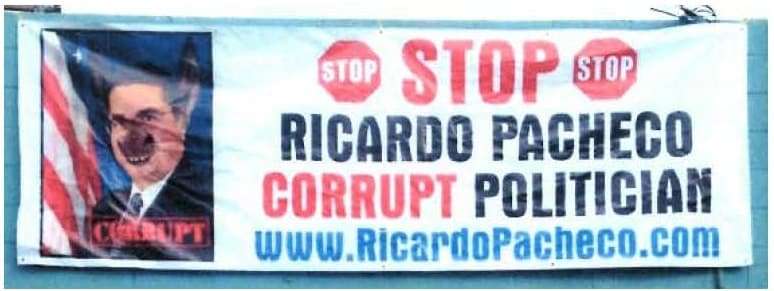

Last week's www.RicardoPacheco.com v. City of Baldwin Park (U.S. District Court for the Central District of California) is an excellent illustration. The sign ordinance there provided:

- A business holding a grand opening or promoting a special product, sale, or event may display one [especially large] temporary sign … for no longer than 30 consecutive days, and for no more than four non-consecutive times during a 12-month period.

- A newly established business may display up to three [large] temporary signs … for no more than 60 days (with the possibility for a 60-day extension).

- For three days before and after Memorial Day, Independence Day, and Veterans Day, an additional flag of up to 12 square feet may be displayed.

- For 45 days before and 14 days after any election for which there are polling places operating in the City, five additional signs of up to 12 square feet and four feet tall may be displayed.

On their face, the restrictions focused on the identity of the speaker, on the speaker's other behavior or the date. But the judge held that the likely justification for the restrictions was a preference for the likely content that signs would have at those places or in those times:

… The Business Provisions prefer some speakers (new businesses and businesses promoting a special event) to other entities. Therefore, the Court finds that the Business Provisions impose a speaker-based distinction. "Characterizing a distinction as speaker based is only the beginning-not the end-of the inquiry." … "… '[L]aws favoring some speakers over others demand strict scrutiny when the legislature's speaker preference reflects a content preference.'" The Court finds that there are "serious questions" as to whether the City's preference for speakers that are businesses, in particular businesses hosting special events, reflects a content preference for commercial speech.

For example, if the City did not hold such a preference, why wouldn't the City permit any entity on non-residential property to display a sign not exceeding 50 square feet for 30 consecutive days up to four non-consecutive times during a 12-month period? "Were the … limitation unrelated to the content of expression, there would have been no perceived need" for the City to permit businesses alone to display additional signs around certain commercial events.

Because the Court finds that the Business Provisions "impose[ ] content-based restrictions on speech, those provisions can stand only if they survive strict scrutiny, which requires the Government to prove that the restriction furthers a compelling interest and is narrowly tailored to achieve that interest." The City makes no attempt to meet this burden….

Because the Additional Flag Provision makes a distinction among different types of events, the Court finds that there are "serious questions" as to whether the City's authorization of an additional flag around Memorial Day, Independence Day, and Veterans Day reflects a content preference for speech concerning those particular holidays. For example, if the City did not hold such a preference, why wouldn't the City permit an additional flag for six days, up to three times per year? "Were the … limitation unrelated to the content of expression, there would have been no perceived need" for the City to permit the display of an additional flag around the three specified holidays….

Plaintiffs challenge the constitutionality of the Election Provision, which authorizes the display of five additional signs-limited to a combined 12 square feet-45 days before and 14 days after any election for which there are polling places in the City…. [P]laintiffs contend that the Election Provision constitutes a content-based restriction on speech because the provision favors speech about electoral politics over other matters of public concern (e.g., the proposed federal budget). The City argues that its regulation of signs near elections is content-neutral because "nothing in the provision limits the content of the thoughts express in the additional signs" and "the extra signs are allowed to address any issue the owner wants."

As described above, an event-based preference for speech may be content based if the regulation targets speech that conveys a certain idea. While the Election Provision seemingly seeks to increase political speech around elections, that does not preclude a finding that the provision is a content-based regulation of speech. Indeed, the Supreme Court has "repeatedly rejected the argument that discriminatory … treatment is suspect under the First Amendment only when the legislature intends to suppress certain ideas."

Even though "[t]his type of ordinance may seem like a perfectly rational way to regulate signs, … a clear and firm rule governing content neutrality is an essential means of protecting the freedom of speech, even if laws that might seem entirely reasonable will sometimes be struck down because of their content-based nature." The Court thus finds that there are "serious questions" as to whether the City's authorization of additional signs around election days reflects a content preference for speech concerning matters related to electoral politics….

Show Comments (0)