The Volokh Conspiracy

Mostly law professors | Sometimes contrarian | Often libertarian | Always independent

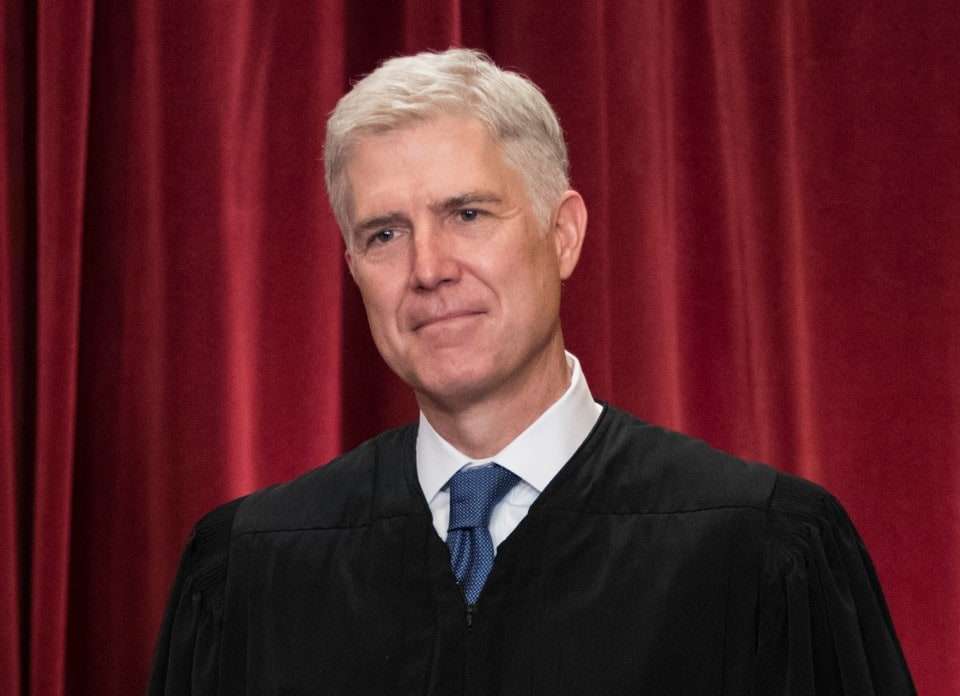

Justice Gorsuch's first opinions reveal a confident textualist

Associate Justice Neil Gorsuch has now written three opinions - a majority, a partial concurrence and a dissent. All three show the Supreme Court's newest justice to be a confident, committed textualist with a distinctive writing style - and a justice who is not afraid to challenge his new colleagues.

First came Gorsuch's opinion for a unanimous court in Henson v. Santander Consumer USA. In this brief opinion - notable for its lack of section breaks - Gorsuch held that a company may seek to collect acquired debts without qualifying as a "debt collector" under the Fair Debt Collection Practices Act. Focusing on the plain language of the statute, Gorsuch concluded that debt collectors under the FDCPA are third-party collection agents, not those who seek to collect debts they are owed themselves.

Many commentators noted the alliteration in the opinion's opening passage:

Disruptive dinnertime calls, downright deceit, and more besides drew Congress's eye to the debt collection industry. From that scrutiny emerged the Fair Debt Collection Practices Act, a statute that authorizes private lawsuits and weighty fines designed to deter wayward collection practices. So perhaps it comes as little surprise that we now face a question about who exactly qualifies as a "debt collector" subject to the Act's rigors. Everyone agrees that the term embraces the repo man-someone hired by a creditor to collect an outstanding debt. But what if you purchase a debt and then try to collect it for yourself- does that make you a "debt collector" too? That's the nub of the dispute now before us.

Later on, Gorsuch stressed that it is not for the courts to override or extend statutory text to conform with legislative purpose.

while it is of course our job to apply faithfully the law Congress has written, it is never our job to rewrite a constitutionally valid statutory text under the banner of speculation about what Congress might have done had it faced a question that, on everyone's account, it never faced. . . . Legislation is, after all, the art of compromise, the limitations expressed in statutory terms often the price of passage, and no statute yet known "pursues its [stated] purpose[ ] at all costs." . . . For these reasons and more besides we will not presume with petitioners that any result consistent with their account of the statute's overarching goal must be the law but will presume more modestly instead "that [the] legislature says . . . what it means and means . . . what it says."

The opinion concludes:

In the end, reasonable people can disagree with how Congress balanced the various social costs and benefits in this area. We have no difficulty imagining, for example, a statute that applies the Act's demands to anyone collecting any debts, anyone collecting debts originated by another, or to some other class of persons still. Neither do we doubt that the evolution of the debt collection business might invite reasonable disagreements on whether Congress should reenter the field and alter the judgments it made in the past. After all, it's hardly unknown for new business models to emerge in response to regulation, and for regulation in turn to address new business models. Constant competition between constable and quarry, regulator and regulated, can come as no surprise in our changing world. But neither should the proper role of the judiciary in that process-to apply, not amend, the work of the People's representatives.

Yesterday, the court issued Maslenjak v. United States. Justice Elena Kagan delivered the opinion of the court, and Gorsuch wrote an opinion concurring-in-part and concurring-in-the-judgment, joined by Justice Clarence Thomas. Here Gorsuch argued that the text of the statute in question called for a more limited holding than that adopted by the court.

The Court holds that the plain text and structure of the statute before us require the Government to prove causation as an element of conviction: The defendant's illegal conduct must, in some manner, cause her naturalization. I agree with this much and concur in Part II-A of the Court's opinion to the extent it so holds. And because the jury wasn't instructed at all about causation, I agree too that reversal is required.

But, respectfully, there I would stop. In an effort to "operational[ize]" the statute's causation requirement, the Court says a great deal more, offering, for example, two newly announced tests, the second with two more subparts, and a new affirmative defense-all while indicating that some of these new tests and defenses may apply only in some but not all cases. . . . The work here is surely thoughtful and may prove entirely sound. But the question presented and the briefing before us focused primarily on whether the statute contains a materiality element, not on the contours of a causation requirement. So the parties have not had the chance to join issue fully on the matters now decided. . . .

Respectfully, it seems to me at least reasonably possible that the crucible of adversarial testing on which we usually depend, along with the experience of our thoughtful colleagues on the district and circuit benches, could yield insights (or reveal pitfalls) we cannot muster guided only by our own lights. . . . For my part, I believe it is work enough for the day to recognize that the statute requires some proof of causation, that the jury instructions here did not, and to allow the parties and courts of appeals to take it from there as they usually do. This Court often speaks most wisely when it speaks last.

Today, the court decided Perry v. Merit Systems Protection Board. The case concerned a technical issue only lawyers could love: Whether the proper forum of MSPB dismissals of mixed cases on jurisdictional grounds is a federal district court or the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Federal Circuit. Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg wrote for a seven-justice majority. Gorsuch dissented, joined by Thomas. Here again, Gorsuch focused on the text.

Gorsuch's dissenting opinion in Perry is very conversational. It begins:

Anthony Perry asks us to tweak a congressional statute-just a little-so that it might (he says) work a bit more efficiently. No doubt his invitation is well meaning. But it's one we should decline all the same. Not only is the business of enacting statutory fixes one that belongs to Congress and not this Court, but taking up Mr. Perry's invitation also seems sure to spell trouble. Look no further than the lower court decisions that have already ventured where Mr. Perry says we should follow. For every statutory "fix" they have offered, more problems have emerged, problems that have only led to more "fixes" still. New challenges come up just as fast as the old ones can be gaveled down. Respectfully, I would decline Mr. Perry's invitation and would instead just follow the words of the statute as written

Later on, Gorsuch explains why courts should confine themselves to the text, even if this may produce a potentially problematic result.

Mr. Perry's is an invitation I would run from fast. If a statute needs repair, there's a constitutionally prescribed way to do it. It's called legislation. To be sure, the demands of bicameralism and presentment are real and the process can be protracted. But the difficulty of making new laws isn't some bug in the constitutional design: it's the point of the design, the better to preserve liberty. Besides, the law of unintended consequences being what it is, judicial tinkering with legislation is sure only to invite trouble. Just consider the line of lower court authority Mr. Perry asks us to begin replicating now in the U. S. Reports. Having said that district courts should sometimes adjudicate civil service disputes, these courts have quickly and necessarily faced questions about how and when they should do so. And without any guidance from Congress on these subjects, the lower courts' solutions have only wound up departing further and further from statutory text-and invited yet more and more questions still. A sort of rolling, case-by-case process of legislative amendment.

His opinion concludes:

At the end of a long day, I just cannot find anything preventing us from applying the statute as written-or heard any good reason for deviating from its terms. Indeed, it's not even clear how overhauling the statute as Mr. Perry wishes would advance the efficiency rationale he touts. The only thing that seems sure to follow from accepting his invitation is all the time and money litigants will spend, and all the ink courts will spill, as they work their way to a wholly remodeled statutory regime. Respectfully, Congress already wrote a perfectly good law. I would follow it.

And that's how the opinion ends.

Hide Comments (0)

Editor's Note: We invite comments and request that they be civil and on-topic. We do not moderate or assume any responsibility for comments, which are owned by the readers who post them. Comments do not represent the views of Reason.com or Reason Foundation. We reserve the right to delete any comment for any reason at any time. Comments may only be edited within 5 minutes of posting. Report abuses.

Please to post comments

Mute this user?

Ban this user?

Un-ban this user?

Nuke this user?

Un-nuke this user?

Flag this comment?

Un-flag this comment?