The Volokh Conspiracy

Mostly law professors | Sometimes contrarian | Often libertarian | Always independent

A glimpse at federal appellate briefs from the 1920s

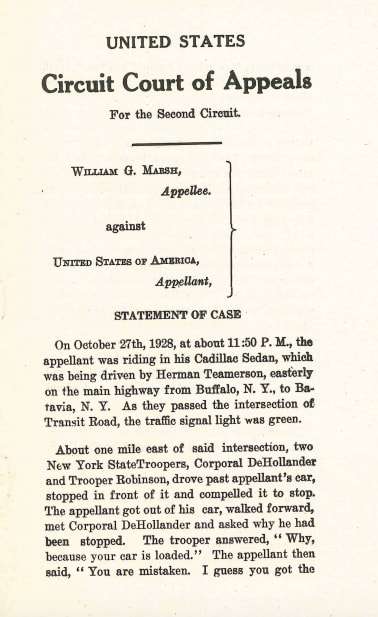

I've become mildly obsessed with a Learned Hand opinion from 1928, Marsh v. United States, 29 F.2d 172 (2d Cir. 1928). I discovered Marsh because I'm writing an article on what I call the cross-enforcement of the Fourth Amendment. The question is, can state officials conduct searches or seizures based on cause to believe federal law was violated? And can federal officials conduct searches or seizures based on cause to believe state law was violated? Officers can search and seize to enforce their own law, but can they search and seize to enforce the law of a different jurisdiction? The issues come up all the time, and yet it turns out there are few settled answers to these questions and courts often disagree on them.

Modern cases often point to Marsh as a leading case on the subject. Marsh involved New York state troopers enforcing the federal Prohibition laws, and at least at first blush appears to have allowed it. My obsession with the case is partially out of respect for the judges who heard the case. Back in the 1920s, the quality of federal appellate opinions varied tremendously. Marsh featured a powerhouse panel: Learned Hand wrote the opinion, and he was joined by his cousin Augustus Hand and former Yale Law dean Thomas Walter Swan. That's as good as it gets.

With that said, my fascination with the case is mostly because reading it in light of modern Fourth Amendment law is rather unsettling. In the opinion, Hand does all sorts of weird and inexplicable things. He focuses on what the officers were subjectively trying to do. He rules on whether the troopers violated statutory law rather than general Fourth Amendment standards. These are big no-nos, according to modern Fourth Amendment doctrine. That led me to wonder why Hand was doing what he was doing. My question was, how did the lawyers and judges in Marsh think the Fourth Amendment worked to make those issues relevant?

Over the past month, I have tried to figure that out by immersing myself in Prohibition-era Fourth Amendment case law. I had read the big Supreme Court cases of the 1920s and early 1930s, but I hadn't read the circuit court decisions or really studied the Volstead Act. In recent weeks, I have read a lot of lower court cases from the period to help crack the mystery of Marsh.

I mention all of this because in the course of trying to understand Marsh, I obtained copies of the briefs filed in the case. I located them at the National Archives at New York City, where you can pay 80 cents a page to have an archivist scan them and send them to you. When I received them, I found the briefs not only fascinating in their substance but also quite beautiful to look at. So I decided to post them, as I figured some others might find the briefs as lovely to look at as I do.

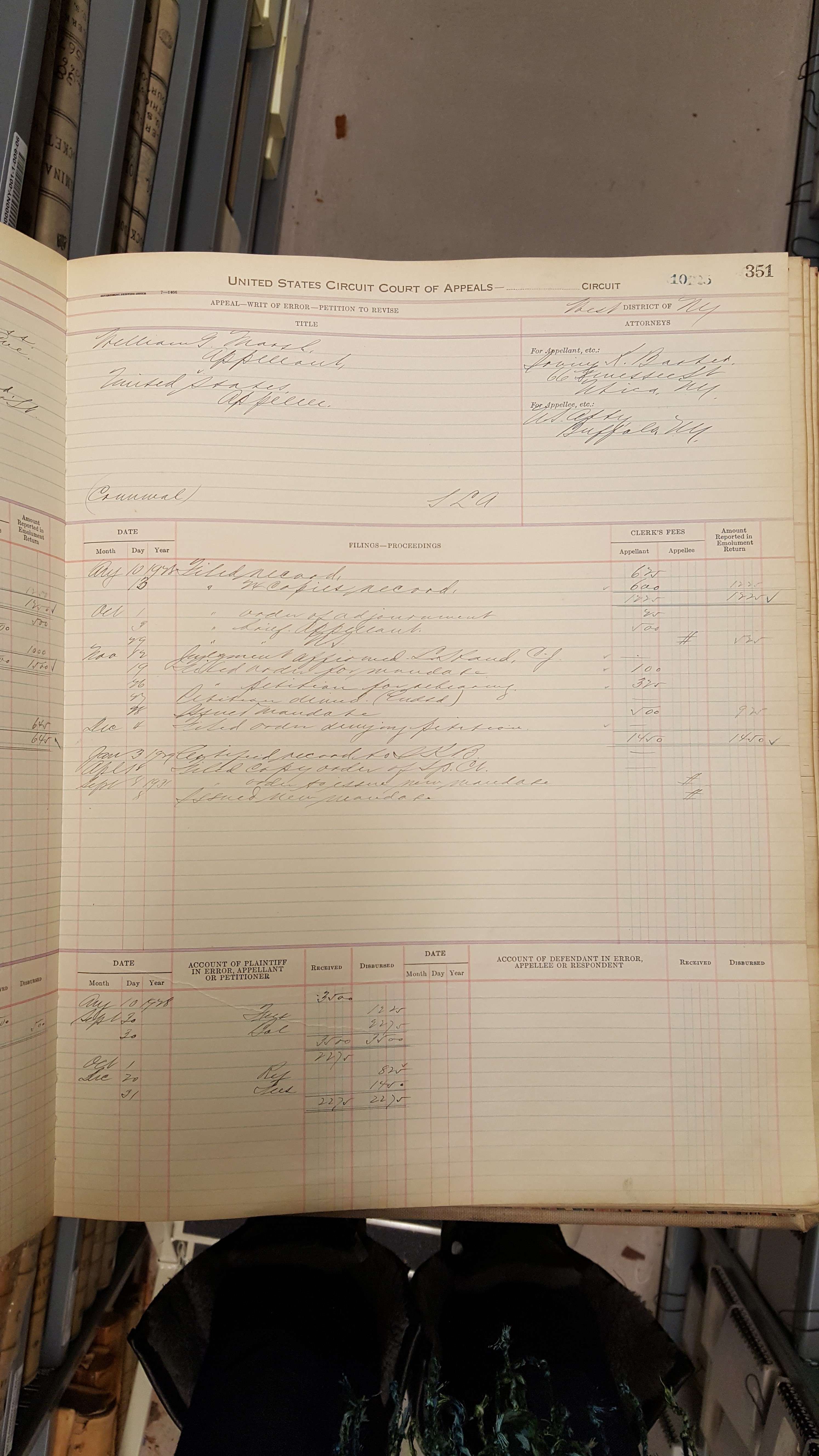

Before I get to the briefs, here's the hand-written docket page. Pretty cool.

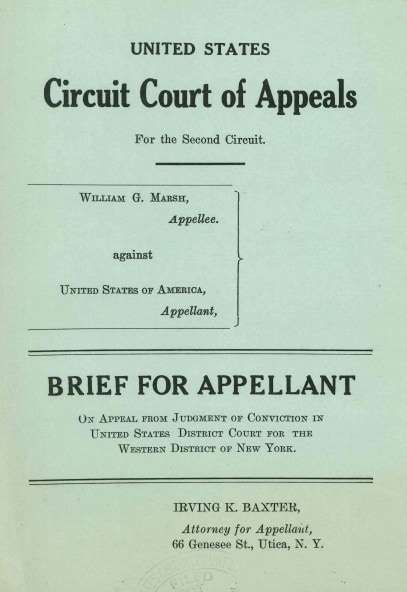

Next, here's the defense brief. You can read the whole thing, but here's just the cover page:

And here's the first page of text.

The lawyer for the defense, Irving K. Baxter, seems like an interesting guy. His 1957 New York Times obituary says that Baxter won gold medals in the high jump and pole vault in the 1900 Paris Olympics. And his obituary flags his work in cases like Marsh: It concludes by saying that Baxter "gained prominence in defending Volstead Act cases."

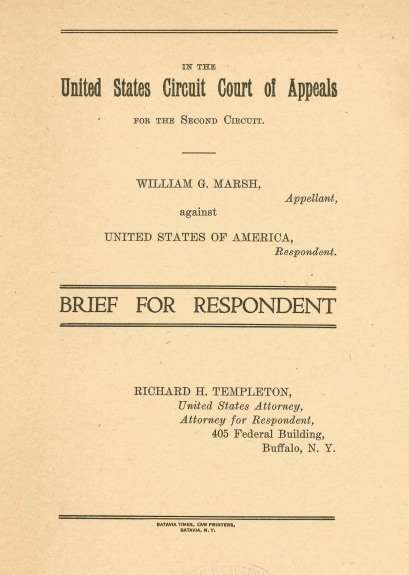

Here's the government's brief. You can read the whole thing pretty quickly, as it's about one-fifth the length of the appellant's brief. The cover page is below.

And here's the signature page. You have to hand it to the government, that argument for Point II sure is concise.

I'll have a lot more to say on Marsh in my article. I've concluded that the mystery of Marsh is a story of slowly-changing assumptions. Back in the 1920s, courts applying the Fourth Amendment operated from a set of assumptions quite different from those of courts today. Over time the old assumptions have been forgotten, and that makes it very easy to be misled by what the old cases mean. But for now I just thought the documents from this 89-year-old case were pretty cool. I hope some other law nerds and legal history buffs might enjoy seeing them.

Show Comments (0)