The Volokh Conspiracy

Mostly law professors | Sometimes contrarian | Often libertarian | Always independent

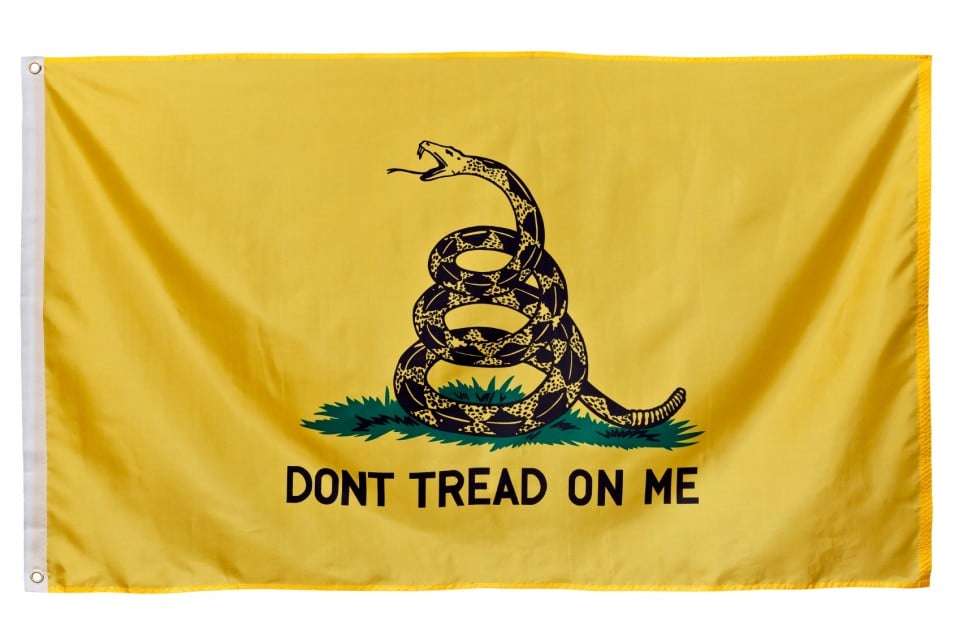

Wearing "Don't Tread on Me" insignia could be punishable racial harassment

[UPDATE: For a follow-up post, see Harvard law prof: "Saying at work that 'Hillary Clinton shouldn't be president because women shouldn't work full-time' may lead to a harassment lawsuit", which responds to a Harvard law professor's defense of the EEOC decision that I discuss below.]

The Equal Employment Opportunity Commission, among its other functions, decides "hostile work environment" harassment claims brought against federal agencies. In doing so, it applies the same legal rules that courts apply to private employers, and that the EEOC follows in deciding whether to sue private employers. The EEOC has already ruled that coworkers' wearing Confederate flag T-shirts can be punishable harassment (a decision that I think is incorrect); and, unsurprisingly, this is extending to other political speech as well. Here's an excerpt from Shelton D. [pseudonym] v. Brennan, 2016 WL 3361228, decided by the EEOC two months ago:

On January 8, 2014, Complainant filed a formal complaint in which he alleged that the Agency subjected him to discrimination on the basis of race (African American) and in reprisal for prior EEO activity when, starting in the fall of 2013, a coworker (C1) repeatedly wore a cap to work with an insignia of the Gadsden Flag, which depicts a coiled rattlesnake and the phrase "Don't Tread on Me."

Complainant stated that he found the cap to be racially offensive to African Americans because the flag was designed by Christopher Gadsden, a "slave trader & owner of slaves." Complainant also alleged that he complained about the cap to management; however, although management assured him C1 would be told not to wear the cap, C1 continued to come to work wearing the offensive cap. Additionally, Complainant alleged that on September 2, 2013, a coworker took a picture of him on the work room floor without his consent. In a decision dated January 29, 2014, the Agency dismissed Complainant's complaint on the basis it failed to state a claim . . . .

Complainant maintains that the Gadsden Flag is a "historical indicator of white resentment against blacks stemming largely from the Tea Party." He notes that the Vice President of the International Association of Black Professional Firefighters cited the Gadsden Flag as the equivalent of the Confederate Battle Flag when he successfully had it removed from a New Haven, Connecticut fire department flagpole.

After a thorough review of the record, it is clear that the Gadsden Flag originated in the Revolutionary War in a non-racial context. Moreover, it is clear that the flag and its slogan have been used to express various non-racial sentiments, such as when it is used in the modern Tea Party political movement, guns rights activism, patriotic displays, and by the military.

However, whatever the historic origins and meaning of the symbol, it also has since been sometimes interpreted to convey racially-tinged messages in some contexts. For example, in June 2014, assailants with connections to white supremacist groups draped the bodies of two murdered police officers with the Gadsden flag during their Las Vegas, Nevada shooting spree. [Footnote: Shooters in Metro ambush that left five dead spoke of white supremacy and a desire to kill police, Las Vegas Review-Journal, June 8, 2014, available online at: http://www.reviewjournal.com/news/las-vegas/shooters-metro-ambush-left-five-dead-spoke-white-supremacy-and-desire-kill-police.] Additionally, in 2014, African-American New Haven firefighters complained about the presence of the Gadsden flag in the workplace on the basis that the symbol was racially insensitive. [Paul Bass, Flag Sparks Fire Department Complaint, New Haven Independent, Feb. 25, 2014, available online at:http://www.newhavenindependent.org/index.php/archives/entry/tea_party_fire_department/.] Certainly, Complainant ascribes racial connotations to the symbol based on observations that it is sometimes displayed in racially-tinged situations.

In light of the ambiguity in the current meaning of this symbol, we find that Complainant's claim must be investigated to determine the specific context in which C1 displayed the symbol in the workplace. In so finding, we are not prejudging the merits of Complainant's complaint. Instead, we are precluding a procedural dismissal that would deprive us of evidence that would illuminate the meaning conveyed by C1's display of the symbol.

A few thoughts:

1. Recall that this is not a case about when private employers may restrict what their employees wear on the job, or even about when government employers may do so. Private employers have very broad power on this, because they aren't bound by the First Amendment (though statutes in some states may constrain employers' power to some extent). Government employers also have fairly broad power to restrict their employees' on-the-job speech and behavior.

Instead, this is a case about the rules that all employers, public or private, must follow, on pain of massive legal liability. The harassment law rules (which, as I noted, are the same for private employers as for the federal government) are imposed by the government acting as sovereign - the area where the First Amendment should provide the most protection - not just the government acting as employer.

2. Nothing in the opinion suggests that the cap wearer said anything racist to Shelton D.; I've read many such EEOC decisions, and they generally list all the significant allegations of harassment. (I can't access the specific complaint in the case, because all that information is kept secret in EEOC proceedings.) Shelton D.'s objection was apparently just to the wearing of the flag, and the ideology that he thinks has become associated with the flag. And the claim that the EEOC is allowing to go forward is simply that the cap, in some social or workplace "context" would be reasonably seen as conveying a racially offensive message.

3. Let's think about how this plays out in the workplace. Imagine that you are a reasonable employer. You don't want to restrict employee speech any more than is necessary, but you also don't want to face the risk of legal liability for allowing speech that the government might label "harassing." An employee comes to you, complaining that a coworker's wearing a "Don't Tread on Me" cap - or having an "All Lives Matter" bumper sticker on a car parked in the employee lot, or "Stop Illegal Immigration" sign on the coworker's cubicle wall - constitutes legally actionable "hostile environment harassment," in violation of federal employment law. The employee claims that in "the specific context" (perhaps based on what has been in the news, or based on what other employees have been saying in lunchroom conversations), this speech is "racially tinged" or "racially insensitive."

Would you feel pressured, by the risk of a lawsuit and of liability, into suppressing speech that expresses such viewpoints? Or would you say, "Nope, I'm not worried about the possibility of liability, I'll let my employees keep talking"? (Again, the question isn't what you may do as a matter of your own judgment about how you would control a private workplace; the question is whether the government is pressuring you to suppress speech that conveys certain viewpoints.)

4. Now let's get to the 2016 election campaign. Say someone wears "Trump/Pence 2016" gear in the workplace, or displays a bumper sticker on his car in the work parking lot, or displays such a sign on his cubicle wall, or just says on some occasions that he's voting for Trump. He doesn't say any racial or religious slurs about Hispanics or Muslims, and doesn't even express any anti-Hispanic or anti-Muslim views (though even such views, I think, should be protected by the First Amendment against the threat of government-imposed liability).

But in "context," a coworker complains, such speech conveys a message "tinged" with racial or religious hostility, or is racially or religiously "insensitive." The coworker threatens to sue. Again, say you are an employer facing such a threat. Would you feel pressured by the risk of liability to restrict the pro-Trump speech? (As before, the question isn't whether you'd be inclined to do that yourself, whether from opposition to Trump, or a desire to avoid controversy that might harm morale; because the First Amendment doesn't apply to private employers, private Internet service providers, private churches, private universities, private landlords, or others, they are not constitutionally constrained from restricting speech. The question is whether you would feel pressured by the government to impose such restrictions, through the threat of being forced to pay money in a civil lawsuit if you don't impose them - and whether the government should be able to pressure such private organizations or individuals to restrict speech this way.)

"There is a place for political discussion in our country, but it shouldn't be the workplace. Accordingly, you may want to consider adopting policies that prohibit political discussions and expression in your workplace, consistent with the applicable state and federal requirements." So writes one employment lawyer, in the Virginia Employment Law Letter. Other employment law experts have likewise urged employers to broadly restrict speech, including speech about presidential politics (that happened with regard to talk about the Clinton/Lewinsky matter).

And while the Virginia Employment Letter proposal would at least be a viewpoint-neutral restriction (though a very broad one), employers are in practice more likely to come down on speech that expresses viewpoints that might trigger harassment claims - such as calls to elect candidates who want to build a wall on the Mexican border, or limit immigration from Muslim countries - than on speech that expresses contrary viewpoints. Workplace harassment law has become a content-based, viewpoint-based speech restriction, including on core political speech. A pretty serious First Amendment problem, I think, for reasons I discuss in more detail here.

Show Comments (0)