The Volokh Conspiracy

Mostly law professors | Sometimes contrarian | Often libertarian | Always independent

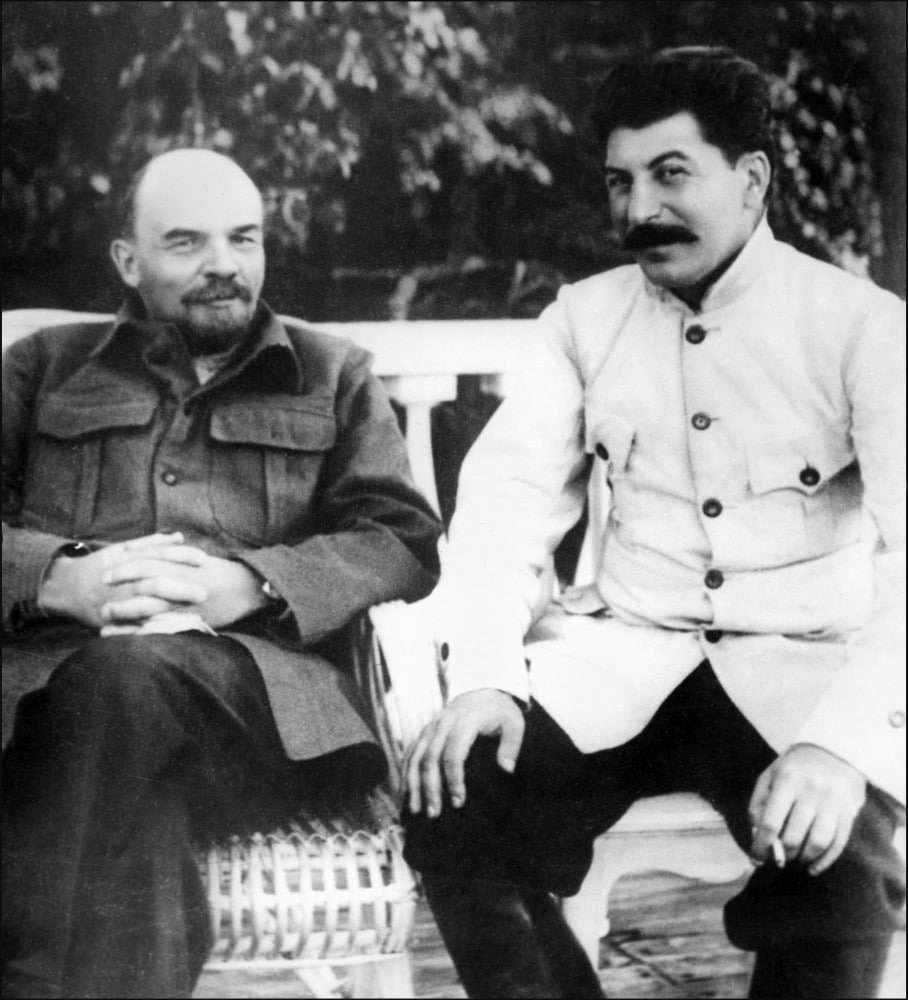

Calling Stalin a "bloodthirsty cannibal" is an insult to bloodthirsty cannibals

Well, that's not what the European Court of Human Rights said, but I hope it was going through their minds. The case, Dzhugashvili v. Russia stemmed from Stalin's grandson suing a Russian newspaper for insulting Stalin's memory. (Come to think of it, Dzhugashvili v. Russia is a good label for decades of Russian history, though in that sense it was also Dzhugashvili v. Georgia, Dzhugashvili v. Poland, and much more.) Here is an excerpt from the summary of the facts:

4. On 22 April 2009 Novaya Gazeta, an opposition newspaper, published in its feature supplement, Pravda Gulaga, an article entitled "Beria pronounced guilty" ("Виновным назначен Берия"), which dealt with the shooting of Polish prisoners in Katyń in 1940. The article was written by Mr Ya., a former investigator of the Russian Chief Military Prosecutor's Office whose duty had been to deal with the rehabilitation of victims of political persecution.

5. The article was written in accusatory terms in respect of the former USSR government and included, among others, the following statements:

"Stalin and the Chekists are bound by much blood, by the extremely serious crimes they committed, first of all, against their own nation";

"Stalin and the members of the Politburo of the VKP(b) who took a legally binding decision to shoot the Poles evaded moral responsibility for the extremely serious crime";

"[T]he former father of nations and, as a matter of fact, a bloodthirsty cannibal is recognised to have been an effective manager";

"Secret protocols to the Molotov-Ribbentrop Pact envisaged that the USSR, despite the legally binding non-aggression treaty with Poland, ought to attack Poland together with Germany. After Germany had started the war against Poland on 1 September 1939, the USSR fulfilled its obligations to Germany and on 17 September 1939 marched into Polish territory".

… 7. Having considered that the article slandered his grandfather, the applicant sued the publishing house, Novaya Gazeta, and the author, Mr Ya., for defamation, seeking a disclaimer and non-pecuniary damages in the amount of 9.5 million roubles (RUB) from the Novaya Gazeta and RUB 0.5 million from the author.

8. On 13 October 2009 the Basmanniy District Court of Moscow held for the journalists and dismissed the claim.

The grandson appealed to the European Court of Human rights; here's an excerpt from the legal analysis:

20. The applicant complained under Articles 6, 10 and 14 that the domestic courts had approved of his ancestor's slander…. [The Court] finds that the applicant's allegations should be examined as in essence relating to an alleged breach of his rights under Article 8 of the Convention, which reads as follows:

"1. Everyone has the right to respect for his private and family life, his home and his correspondence.

2. There shall be no interference by a public authority with the exercise of this right except such as is in accordance with the law and is necessary in a democratic society in the interests of national security, public safety or the economic well-being of the country, for the prevention of disorder or crime, for the protection of health or morals, or for the protection of the rights and freedoms of others."

… 30. The Court … deems it appropriate to distinguish between defamatory attacks on private persons, whose reputation as part and parcel of their families' reputation remains within the scope of Article 8, and legitimate criticism of public figures who, by taking up leadership roles, expose themselves to outside scrutiny.

31. The first publication contributed to a historical debate over the Katyń events and dealt, among other things, with the role which the former Soviet leaders had presumably played therein. The second publication contained, as a matter of fact, the author's interpretations of the domestic court's findings in connection with the first dispute and hence, in a way, can be seen as a continuation of the same discussion.

32. The Court notes that historical events of great importance which affected the destinies of multitudes of people, as well as the historical figures involved therein and responsible for them, inevitably remain open to public historical scrutiny and criticism, as they present a matter of general interest for society.

33. Given that cases such as the present one require the right to respect for private life to be balanced against the right to freedom of expression, the Court reiterates that it is an integral part of freedom of expression, guaranteed under Article 10 of the Convention, to seek historical truth. It is not the Court's role to arbitrate the underlying historical issues, which are part of a continuing debate between historians (see Chauvy and Others v. France, no. 64915/01, § 69, ECHR 2004‑VI). A contrary finding would open the way to a judicial intervention in historical debate and inevitably shift the respective historical discussions from public forums to courtrooms….

36. Having regard to the above, the Court considers that the applicant's complaint under Article 8 of the Convention in this part is to be rejected as manifestly ill-founded, pursuant to Article 35 §§ 3 and 4 of the Convention.

Show Comments (0)